Rose’s story

On examination, Rose had no signs of a unilateral vestibulopathy. Specifically, there was no nystagmus at rest or evoked by gaze or head-shaking. The result of a horizontal head impulse test (in which the examiner manually delivers high acceleration, 20°–30° head rotations in the horizontal plane to assess the horizontal vestibulo-ocular reflex while the patient fixes their gaze on a target) was normal, with no evidence of a “catch-up saccade” after head movement. A left Dix–Hallpike test (in which the patient is arched backwards by the examiner while their head is turned 45° to the left) revealed vigorous upbeating counterclockwise (leftward) torsional nystagmus that appeared after a latency of 5–10 seconds, reached a crescendo over 30 seconds and then rapidly slowed down (Video 1).

Vertigo refers to a sensation of movement (spinning, tilting, rocking) of the individual or their surrounds. The common causes of vertigo can often be differentiated on the basis of their history. Benign positional vertigo (BPV) typically causes episodic vertigo lasting seconds and is precipitated by movement of the head, whereas Meniere’s disease causes episodic vertigo lasting hours, is usually spontaneous and is associated with aural fullness, tinnitus, and hearing loss or fluctuation. In contrast, vestibular neuritis causes persistent vertigo lasting 1 or more days, in the absence of associated neurological symptoms or signs. When BPV is suspected as the cause of vertigo, history-taking should extract the brevity and positional character of the vertigo, look for the presence or absence of features of other vestibular disorders, and determine whether an underlying cause can be identified. Older patients with BPV can also present with imbalance or falls rather than positional vertigo.1

The differential diagnoses for episodic positional vertigo are summarised in Box 1. In Rose’s case, positional vertigo lasted only seconds and was not associated with aural symptoms or headache. Her sensation of being pushed to one side (“lateropulsion”) was probably caused by movement of otoconia within the duct of the left posterior semicircular canal.

The typical nystagmus of BPV that results from canalithiasis (Box 2) is preceded by a latency of 2–15 seconds after head movement. It is paroxysmal, rises to a crescendo and abates within 60 seconds. It is elicited by positioning the head in a way that the affected canal is vertical and aligned with gravity. Stimulation of a given canal by the movement of otoconia provokes nystagmus in the plane of that canal, and is thus unique to that canal. The nystagmus reverses direction by moving the head in the opposite direction (eg, returning to the upright position). The nystagmus fatigues on repetition of the Dix–Hallpike test.

Observations from electrical stimulation of nerves innervating individual semicircular canals and three-dimensional analysis of eye movements recorded from single-canal BPV confirms that activation of a given canal evokes nystagmus with a rotational axis perpendicular to that canal.2 The left Dix–Hallpike test in this patient evoked paroxysmal upbeating and counterclockwise torsional nystagmus (from the patient’s perspective) indicative of left posterior canal activation (Box 3, Video 1).

Secondary or “symptomatic” BPV (where BPV is a symptom of an underlying inner ear disorder) can be caused by inner ear diseases (such as vestibular neuritis and Meniere’s disease), otological surgery and head injuries.3

Posterior canalithiasis — BPV affecting one of the posterior canals — is the most common canalithiasis. It can be treated at the bedside with an Epley manoeuvre (Box 4, Video 4), which has been shown to be effective in randomised controlled trials (Grade A evidence).4 The manoeuvre is easy to learn and can be performed by medical practitioners, allied health professionals and, in some instances, patients themselves.

Because of the unequivocal demonstration of paroxysmal positional vertigo and nystagmus, as well as lack of a history of head injury, prolonged vertigo or physical signs of a peripheral vestibulopathy, Rose was diagnosed with primary idiopathic BPV affecting the left posterior canal. She was treated at the bedside with an Epley manoeuvre (Box 4) and instructed to avoid sleeping on her left side for 1 week. She experienced disequilibrium over the next 48 hours and minor residual symptoms for 1 week. She was asymptomatic 1 week after the treatment.

During an Epley manoeuvre, otoconia can sometimes inadvertently be dislodged from the posterior canal and drop into the horizontal canal, resulting in severe vertigo accompanied by horizontal nystagmus. The side-lying test (or roll test) can be used to test for horizontal canal BPV. The patient is quickly turned to the left and right lateral positions as the examiner observes the eyes. In left horizontal canal BPV, left-beating horizontal nystagmus will be observed in the left lateral position. Less intense right-beating horizontal nystagmus will be observed in the right lateral position. Iatrogenic horizontal canalithiasis should be treated with the same manoeuvre used for treatment of BPV affecting the horizontal canal;4 this is sometimes called the barbecue manoeuvre, as the patient imitates a spit roast being rotated (Box 5, Video 5).

Anterior canal BPV is exceedingly rare. Left anterior canal BPV can be treated by placing the patient in the right Hallpike position and performing an Epley manoeuvre. Alternatively, a deep Dix–Hallpike test (with the right ear down) followed by a rapid return to the upright position can also be used (Video 6).

After a single successful Epley manoeuvre, it is reassuring to repeat the Dix–Hallpike test and demonstrate absence of nystagmus and vertigo. Repeated testing can cause habituation of the canal receptors, resulting in a false negative result from the Dix–Hallpike test. Patients can be advised to sleep on two or three pillows, on the unaffected side, for 1 week. Although disequilibrium may persist for several days, they should remain physically active and maintain a normal range of head movements. Neck immobilisation with soft collars promotes fear of head movement and may contribute to neck pain and tension headaches. If positional vertigo persists, patients should have a follow-up assessment within 1 week. Patients have previously been advised to sleep upright for 48 hours after treatment of BPV, but recent studies show no advantage of this (Grade B evidence).5

Bedside treatment of BPV is within the capability of any medical practitioner, and some physiotherapists and nurses are adept at treating BPV. Websites that show patients how they can self-treat their BPV have also led to home Epley manoeuvres. When the patient is able to clearly identify the affected side and when the Epley manoeuvre is not technically difficult (ie, when the patient is mobile enough to perform the manoeuvre unassisted), he or she can be taught (by a health care professional) how to self-treat. It is important to caution the patient that there are many BPV subtypes, of which the home Epley manoeuvre treats only one (albeit the most common one). If no improvement is noticed after a home repositioning manoeuvre, further medical advice should be sought. For patients with a limited range of neck movements, the Semont manoeuvre is an alternative method of treating posterior canalithiasis (Box 6, Video 7).

Subjective BPV: Benign positional nystagmus is more likely to be detected when the patient does not fix their gaze. In contrast, when bedside examination with visual fixation elicits clearly lateralised positional vertigo without nystagmus (subjective BPV, in which the patient feels as though they are spinning), the symptomatic side should be treated with a particle-repositioning manoeuvre.6 If the patient’s history is characteristic of BPV but neither nystagmus nor vertigo can be provoked, and there are no physical signs of vestibular impairment, it is more fruitful to repeat the bedside assessment on one or more symptomatic days, rather than seek an alternative diagnosis.7

BPV with motion sensitivity that impedes treatment: Motion-sensitive patients with BPV — including those with migraine, severe post-traumatic BPV or horizontal canal BPV — can develop intense nausea and vomiting during testing and treatment. Such patients should fast for 4 hours before treatment and be premedicated with an antiemetic (eg, intramuscular prochlorperazine or sublingual ondansetron) and a vestibular suppressant (eg, oral diazepam or oral lorazepam). However, these drugs do not reduce time to symptom resolution.4

Recurrent BPV: Long-term follow-up studies show a 50% recurrence rate for BPV over 10 years; in most cases, BPV recurs in the first year after repositioning.8 In a few patients, BPV is refractory to multiple bedside repositioning treatments. If the patient can perform the Epley manoeuvre (perhaps with the help of a family member), daily home Epley manoeuvres, with weekly supervised manoeuvres by a trained physician, therapist or nurse, are recommended. Mechanical particle-repositioning devices (see below) have high success rates for treating recurrent BPV that is refractory to multiple bedside repositioning treatments2,9 but it is not known whether these devices are more efficacious than frequent regular bedside repositioning manoeuvres.

Atypical positional nystagmus: Rarely, central vestibular disorders can give rise to positional nystagmus, which can be mistaken for BPV. For example, posterior fossa lesions, especially small cerebellar strokes, can produce paroxysmal positional nystagmus, which can be difficult to differentiate from BPV.10 In addition, spontaneous horizontal nystagmus from acute peripheral vestibulopathies may be enhanced by Dix–Hallpike testing. However, unlike the horizontal (paroxysmal) nystagmus observed in horizontal canal BPV (which changes direction with either ear down), enhanced spontaneous nystagmus is consistently unidirectional. For example, spontaneous nystagmus from a right-sided vestibular neuritis will be left beating in the left lateral and right lateral positions. In contrast, nystagmus from left horizontal canal BPV will be vigorously left beating in the left lateral position and will beat less vigorously to the right in the right lateral position. Low-velocity sustained horizontal, vertical or torsional nystagmus can be found in patients with clinically definite vestibular migraine.11

Mechanical repositioning: The Epley Omniax System (Vesticon, Portland, Ore, USA) is a multi-axial motorised chair that can position and move a seated patient in the plane of any one of the six semicircular canals. It uses real-time infrared video-oculography to enable observation of nystagmus during provocative testing. Studies indicate success rates of 99.3%, 89.2% and 63.2%, respectively, for treatment of posterior, horizontal and anterior canal BPV in a single manoeuvre, which are higher than success rates reported for bedside particle-repositioning manoeuvres.9 However, no randomised trials have directly compared the efficacy of bedside repositioning with that of mechanical repositioning.

Canal plugging: Posterior semicircular canal occlusion is an effective treatment option for debilitating posterior canal BPV that is unresponsive to bedside repositioning. In the largest case series reported to date, all but one of 44 patients who underwent this procedure were relieved of BPV on follow-up between 6 months and 12 years.12 One patient with normal preoperative hearing developed delayed sudden hearing loss in the treated ear at 3 months. Postoperative imbalance and motion sensitivity (up to 4 weeks) was reported in all patients, with more prolonged symptoms in six.

1 Differential diagnoses of episodic positional vertigo

Benign positional vertigo: lateralised vertigo lasting seconds, brought on by turning over in bed, arching backwards or rising from a stooped position. It can be associated with head trauma, surgery or vestibular neuritis.

Vestibular migraine: non-lateralised positional vertigo lasting seconds to days. It may be associated with migraine headache, photophobia, phonophobia or motion sensitivity.

Meniere’s disease: acute spontaneous vertigo lasting minutes to hours. It is usually associated with aural fullness, tinnitus, and hearing loss or fluctuation. Positional disequilibrium or vertigo may also occur.

Vestibular paroxysmia: vertigo lasting seconds, provoked by changes in head position, with hearing loss or tinnitus that is permanent or present during the attack. Audiovestibular tests may show unilateral impairment, and the condition is responsive to carbamazepine

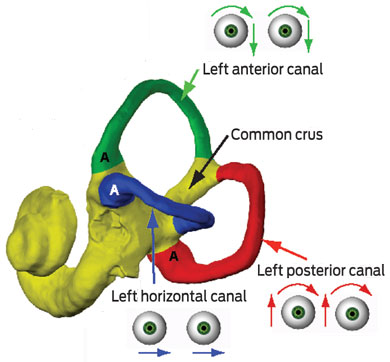

3 The left inner ear, showing nystagmus profiles of benign positional vertigo arising from each semicircular canal

Each canal is made up of a tubular duct ending in a distended ampulla (A) which contains semicircular canal receptors embedded within its cupula. 1. Left posterior canal — a left Dix–Hallpike test evokes upbeating counterclockwise torsional nystagmus (from the patient’s perspective) (Video 1). 2. Left horizontal canal — a side-lying test (or roll test) evokes horizontal nystagmus (Video 2). 3. Left anterior canal — a left or right Dix–Hallpike test evokes downbeating counterclockwise torsional nystagmus (from the patient’s perspective) (Video 3).

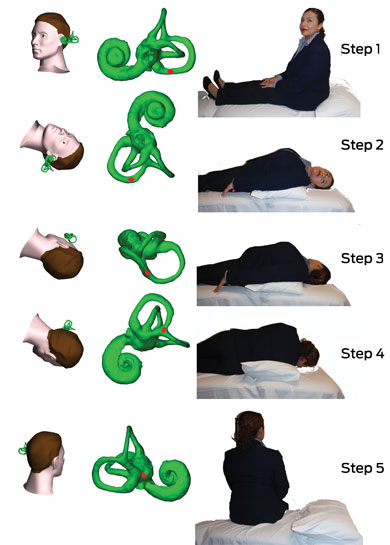

4 Epley manoeuvre for treating left posterior canalithiasis

Step 1: The patient sits up in bed with her head rotated 45° to the left, to bring the posterior canal into the sagittal plane. Step 2: The patient is lowered rapidly until her head hangs backwards, while still turned to the left, and is held in this position for 30 seconds or until the vertigo and nystagmus abate. Step 3: The patient’s head is slowly rotated 90° toward the right side and held for 30 seconds. Step 4: The patient is rotated another 90° to achieve the nose-down position. Step 5: The patient sits up. These steps are animated in Video 4.

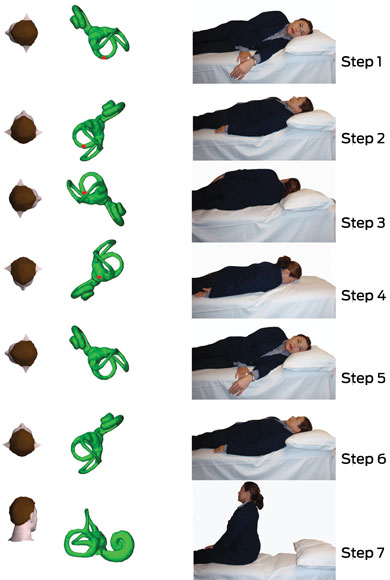

5 Barbecue manoeuvre for treating left horizontal canalithiasis

Step 1: The patient lies on her left side. Steps 2–6: Using 90° rotations, the patient’s head and body are rolled away from the left side, with each position being held for 30 seconds. Step 7: The patient returns to the supine nose-up position and is rapidly returned to the sitting position. These steps are animated in Video 5.

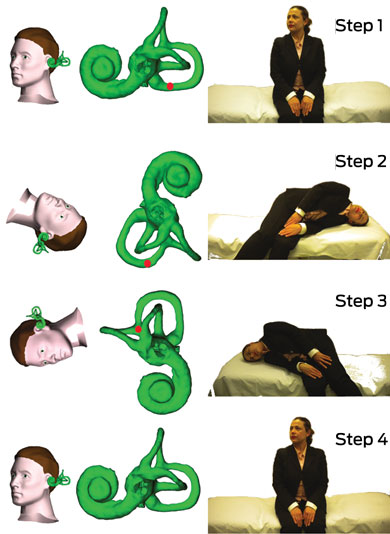

6 Semont manoeuvre for treating left posterior canalithiasis in patients with limited neck movement

Step 1: The patient sits sideways on the bed with her head rotated 45° to the right, to bring the left posterior canal into the coronal plane. Step 2: The patient is rapidly layed down on the left side in a head-hanging position. Step 3: After 1 minute, the patient is moved to the opposite side, with her head still rotated 45° to the right. Step 4: After 1 minute, the patient returns to the upright position. These steps are animated in Video 7.

- Miriam S Welgampola1,2

- Andrew Bradshaw1

- G Michael Halmagyi1,2

- 1 Department of Neurology, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW.

- 2 Central Clinical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW.

Miriam Welgampola and Michael Halmagyi are supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council grant for research on diagnosis and management of intractable BPV (NHMRC Project Grant APP1010017). Miriam Welgampola is the recipient of a Garnett Passe and Rodney Williams Memorial Foundation Senior/Principal Research Fellowship.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Lawson J, Johnson I, Bamiou DE, Newton JL. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: clinical characteristics of dizzy patients referred to a Falls and Syncope Unit. QJM 2005; 98: 357-364.

- 2. Aw ST, Todd MJ, Aw GE, et al. Benign positional nystagmus: a study of its three-dimensional spatio-temporal characteristics. Neurology 2005; 64: 1897-1905.

- 3. Cremer PD, Karlberg M, Hall K, et al. What inner ear diseases cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Acta Otolaryngol 2000; 120: 380-358.

- 4. Fife TD, Iverson DJ, Lempert T, Furman JM, et al. Practice parameter: therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2008; 70: 2067-2074.

- 5. Casqueiro JC, Ayala A, Monedero G. No more postural restrictions in posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2008; 29: 706-709.

- 6. Haynes DS, Resser JR, Labadie RF, et al. Treatment of benign positional vertigo using the Semont maneuver: efficacy in patients presenting without nystagmus. Laryngoscope 2002; 112: 796-801.

- 7. Pollak L. The importance of repeated clinical examination in patients with suspected benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otol Neurotol 2009; 30: 356-358.

- 8. Brandt T, Huppert D, Hecht J, et al. Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo: a long-term follow-up (6–17 years) of 125 patients. Acta Otolaryngol 2006; 126: 160-163.

- 9. Nakayama M, Epley JM. BPPV and variants: improved treatment results with automated, nystagmus-based repositioning. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005; 133: 107-112.

- 10. Buttner U, Helmchen CH, Brandt TH. Diagnostic criteria for central versus peripheral positioning nystagmus and vertigo: a review. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1999; 119: 1-5.

- 11. Von Brevern M, Radtke A, Clarke AH, Lempert T. Migrainous vertigo presenting as episodic positional vertigo. Neurology 2004; 62: 469-472.

- 12. Agrawal SK, Parnes LS. Human experience with canal plugging. Ann NY Acad Sci 2001; 942: 300-305.

Summary

Benign positional vertigo (BPV) is the most common cause of episodic vertigo. It results from activation of semicircular canal receptors by the movement of calcium carbonate particles (otoconia) which dislodge from the otolith membranes.

During changes in head position, the otoconia either float freely within the semicircular canal duct (canalithiasis) or adhere to and move with the cupula of the canal (cupulolithiasis).

BPV from canalithiasis evokes brief spells of vertigo lasting seconds and can be diagnosed at the bedside by provoking paroxysmal vertigo and nystagmus on tilting the head in the plane of the affected canal. The nystagmus has a unique rotational axis perpendicular to the affected canal.

The Dix–Hallpike test is a simple means of confirming the diagnosis in patients presenting with episodic vertigo or imbalance. Audiovestibular tests are only indicated if a symptomatic primary underlying inner ear disease is suspected.

In over 80% of patients, BPV can be treated successfully with a single bedside Epley (particle-repositioning) manoeuvre, which can be performed by any medical practitioner.