Clinical records

Patient 1

She underwent cardiac catheterisation, which revealed a dilated aortic root and ascending aorta, measuring 4.3 cm and 6 cm, respectively, with normal coronary arteries. Syphilis serology, requested because of the dilated aortic root, was positive with a rapid plasma reagin titre of 1 : 2 and a reactive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test. Because of penicillin allergy, intravenous ceftriaxone 1 g daily was given for 21 days. No lumbar puncture was performed.

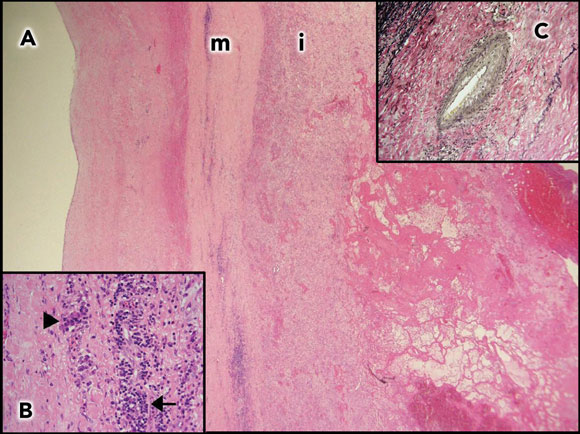

She had an aortic valve replacement, and replacement of the ascending aorta with a synthetic graft. Macroscopically, the aortic wall was extremely thick. Histological sections showed features consistent with syphilitic aortitis (Figure 1). Her recovery was slow, but she is now living independently 15 months after surgery.

|

1 Aortic wall of Patient 1  A: Aortic wall (2 x objective) with thickened media (m) and intima (i). |

Patient 2

A 40-year-old Indonesian man who had lived in Australia for 14 years presented with acute onset severe central chest pain, on a background of similar but less severe pain over the previous 2 months. He smoked one packet of cigarettes per day, but had no other risk factors for coronary artery disease. He was in a monogamous heterosexual relationship of 18 months. His electrocardiogram revealed 3 mm ST elevation in the anterior leads (V1–3) and reciprocal ST depression in the inferior leads (II, III, aVF). His serum troponin level was 4.9 μg/L (reference range, 0–0.4 μg/L).

A coronary angiogram revealed a completely occluded left main coronary artery at the ostium, and a 90% ostial lesion of his right coronary artery; the remainder of his right coronary system was clear of disease (Figure 2). He underwent emergency coronary artery bypass grafting. The operative notes do not comment on the appearance of the native coronary arteries, nor were these sent for histological examination. An aortic wall biopsy showed mild degenerative changes only — syphilis could not be excluded as causing these changes. In view of the bilateral coronary ostial lesions, syphilis serology was performed.

His rapid plasma reagin titre was 1 : 64, together with a reactive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination test. Treatment with intravenous penicillin 1.8 g every 4 hours was given for 15 days, and prednisolone 25 mg twice daily for 2 days to prevent a Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction. The patient declined a lumbar puncture.

|

2 Coronary angiograms of Patient 2  \ \

A: Tapering of the aortic root (thin arrows) and left main coronary stump (arrowhead). |

The details of these two patients and another three patients seen between 1998 and 2004 are summarised in the Box. Although confirmatory histology of cardiovascular syphilis was not available for four of the five patients, this was considered the most likely diagnosis. All patients were born outside Australia. None of the three men reported having sex with men. No patients reported a history of syphilis.

Syphilis has become a rare disease, although peaks of syphilis notifications occurred in Australia in the mid 1970s to mid 1980s and again more recently.1 Clinicians need to be aware of the manifestations of syphilis, and to consider the diagnosis outside the groups considered at risk of this infection in the modern era, such as men who have unprotected sex with other men. The five patients in our series ranged in age from 40 to 77 years. Notably, all were born overseas, and none belonged to a group considered at high risk of syphilis in the contemporary Australian context. Serology was consistent with acquisition of infection in the distant past in four of the five patients.

Among patients with untreated syphilis, aortitis occurs in up to 70%–80%, and the clinically apparent manifestations of aortic regurgitation, coronary ostial stenosis and aortic aneurysms are seen in 10%–15%.2 Although aortic regurgitation is rarely caused by syphilis, it occurs in 20%–30% of patients with syphilitic aortitis.3 Coronary ostial lesions may be seen in 20%–25% of patients with syphilitic aortitis,3 but it is uncommon for such coronary ostial lesions to lead to acute myocardial infarction.4 In contrast, ostial lesions are only seen in 0.1% of patients with coronary artery disease, and bilateral lesions are even less common.5 The high plasma reagin titre seen in Patient 2 is also unusual in cardiovascular syphilis, but has been previously noted.6

Lessons from practice

Cardiovascular syphilis may occur in patients outside of the usual risk groups for syphilis.

Testing for syphilis serology should be considered in patients with aortic regurgitation, and particularly bilateral coronary ostial lesions or aortic aneurysms.

Cerebrospinal fluid should be examined in patients with cardiovascular syphilis to exclude neurosyphilis.

Patients with bilateral coronary ostial lesions but no distal coronary artery disease and those with ascending aortic aneurysms should be screened for syphilis. Screening should be considered for people with aortic regurgitation, especially those with risk factors, including birth in a country where syphilis has been or continues to be common. Although rates of neurosyphilis are low in patients with cardiovascular syphilis,3,7 a cerebrospinal fluid examination is recommended to exclude neurosyphilis. In addition, screening for other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, should be considered, and appropriate contact tracing instituted. Sexual transmission of syphilis occurs only when mucocutaneous lesions are present, but long-term sexual partners of patients with late latent or tertiary syphilis should be screened serologically.

The duration and route of penicillin therapy for cardiovascular syphilis are controversial. Each of our five patients received a different therapy. Penicillin has never been formally evaluated as treatment for cardiovascular syphilis, but a study from the 1950s showed that few patients had progressive disease after penicillin therapy, and up to 60% reported symptomatic relief.8,9 The Australian Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic suggest intravenous benzylpenicillin for 15 days,10 the Australian National management guidelines for sexually transmissible infections suggest intramuscular procaine penicillin for 20 days,11 and the World Health Organization, European and United States guidelines suggest intramuscular benzathine penicillin 2.4 million units once weekly for three doses.12-14 These variations reflect the paucity of good clinical data comparing the different regimens. Although definitive evidence of the efficacy of benzathine penicillin is lacking, there is also no evidence to the contrary. There is little evidence that Jarisch–Herxheimer reactions complicate treatment of cardiovascular syphilis.8,9,15

Cardiovascular syphilis: one proven and four presumptive cases

- 1. Jin F, Prestage GP, Kippax SC, et al. Epidemic syphilis among homosexually active men in Sydney. Med J Aust 2005; 183: 179-183. <MJA full text>

- 2. Jackman JD, Radolf JD. Cardiovascular syphilis. Am J Med 1989; 87: 425-433.

- 3. Heggtveit HA. Syphilitic aortitis: a clinicopathologic autopsy study of 100 cases, 1950 to 1960. Circulation 1964; 29: 346-355.

- 4. Scharfman WB, Wallach JB, Angrist A. Myocardial infarction due to syphilitic coronary ostial stenosis. Am Heart J 1950; 40: 603-613.

- 5. Yamanaka O, Hobbs RE. Solitary ostial coronary artery stenosis. Jpn Circ J 1993; 57: 404-410.

- 6. Vlahakes GJ, Hanna GJ, Mark EJ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 10-1998. A 46-year-old man with chest pain and coronary ostial stenosis. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 897-903.

- 7. Peters JJ, Peers JH, Olansky S, et al. Untreated syphilis in the male Negro: pathologic findings in syphilitic and non-syphilitic patients. J Chron Dis 1955; 1: 127-148.

- 8. Eisenberg H, Brandfonbrener M. Observations on penicillin treated cardiovascular syphilis. I. Uncomplicated aortitis. Am J Syph Gonorrhea Vener Dis 1953; 37: 439-441.

- 9. Eisenberg H, Brandfonbrener M. Observations on penicillin treated cardiovascular syphilis. II. Complicated aortitis. Am J Syph Gonorrhea Vener Dis 1953; 37: 442-448.

- 10. Therapeutic Guidelines Writing Group. Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic. Version 12. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2003.

- 11. Venereology Society of Victoria. National management guidelines for sexually transmissible infections. Melbourne: Venereology Society of Victoria, 2002. Available at: http://www.mshc.org.au/upload/National%20Management%20Guidelines%20for%20STIs.pdf (accessed Jan 2006).

- 12. World Health Organization Europe. Review of current evidence and comparison of guidelines for effective syphilis treatment in Europe. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/document/e81699.pdf (accessed Jan 2006).

- 13. Goh B, van Voorst Vader P. European guideline for the management of syphilis. Int J STD AIDS 2001; 12 Suppl 3: 14-26.

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR Recomm Rep 2002; 51: 1-78.

- 15. Edeiken J, Ford WT, Falk MS, Stokes JH. Further observations on penicillin-treated cardiovascular syphilis. Circulation 1952; 6: 267-275.

Many thanks to Charles Neal from the Cardiology Department for the angiographic images, and Moira Finlay from the Pathology Department for the histopathology slides.

None identified.