The known: Despite decades of promoting equity, sex and gender discrimination persists in health research and practice, with adverse consequences for the health of women, girls and gender‐diverse people. Clinical guidelines, which are based on research, influence health systems and practice, but their standard of sex and gender awareness in Australia is unknown.

The new: Of 80 Australian clinical guidelines that we surveyed, 65 referred to clinical practice concerning sex, but only 12 included gender‐relevant practice and only four defined “sex” and “gender”.

The implications: Guideline developers should assess research evidence for its treatment of sex and gender, to enable strategies to counter inequity and discrimination.

Women and girls face greater barriers than men and boys in access to health information and services,1 including restrictions on mobility, limited access to decision‐making power, lower literacy rates, discriminatory attitudes of communities and health care providers, and health care providers’ lack of training and awareness about the health needs and challenges of women and girls.2,3 People with diverse gender identities who, by definition, do not fit binary sex or gender norms, confront violence, stigma and discrimination, including in health care settings.4 Consequently, they are at higher risk of human immunodeficiency virus infection, chronic health conditions, and mental health problems such as suicide.4 Although the most obvious disadvantages of rigid gender norms are evident in gender minorities and women, such restrictions adversely affect everyone by failing to account for individual differences and preferences. Understanding these differences and their ramifications is critical to improving health outcomes and quality of life for all.

The terms “sex” and “gender” are often used interchangeably, but health research and policies rely on precise language. While prescription of medications must consider attributions of biological sex, holistic health care must respond to gender (a psychosocial identity construct) to address social determinants of health.5 These concepts and the adverse effects of sex and gender binaries are discussed elsewhere.6,7,8

Health research has a history of sex and gender bias.9,10 As the male body was considered standard, data were collected solely from men and extrapolated to women.8 Only since 1989 have the US National Institutes of Health included women in clinical research, legislated in 1993.11 The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) recently published its first Statement on sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation in health and medical research.12 Despite decades of promoting equity, discrimination persists. Inequity has been reproduced and reinforced by health research and health care systems that are sex and gender biased, with consequent adverse effects on health.13 Inadequate consideration of the role of sex in research and practice has been demonstrated in Cochrane reviews,14 clinical trials,15 and Australia's top ten medical journals.16

To facilitate the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of achieving gender equality and empowerment of women and girls (goal 5) and ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all (goal 3), health care must be free from sex and gender discrimination. Clinical guidelines are designed to ensure evidence‐based health care practice.17 To remove gender bias in clinical research, medical education and teaching practice, clinical guidelines must set the standard for equity. However, there is evidence of inconsistent reporting of sex and gender in Canadian guidelines.18 An analysis of European guidelines is underway.19 In Australia, women are under‐represented on clinical guideline development panels20 but, to our knowledge, the sex and gender content of guidelines has not previously been investigated. Therefore, our aim was to appraise Australian clinical guidelines for their inclusion of sex and gender.

Method

The survey results reported here are part of a larger review commissioned by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care to inform strategies to reduce sex and gender bias and disparities in the health care system and in clinical practice.21 The review aligns with priority area 4 of Working for Women: A Strategy for Gender Equality.22 A survey of Australian clinical guidelines was included in the literature review to answer the question of whether there are guidelines that do not take into account sex and gender differences.

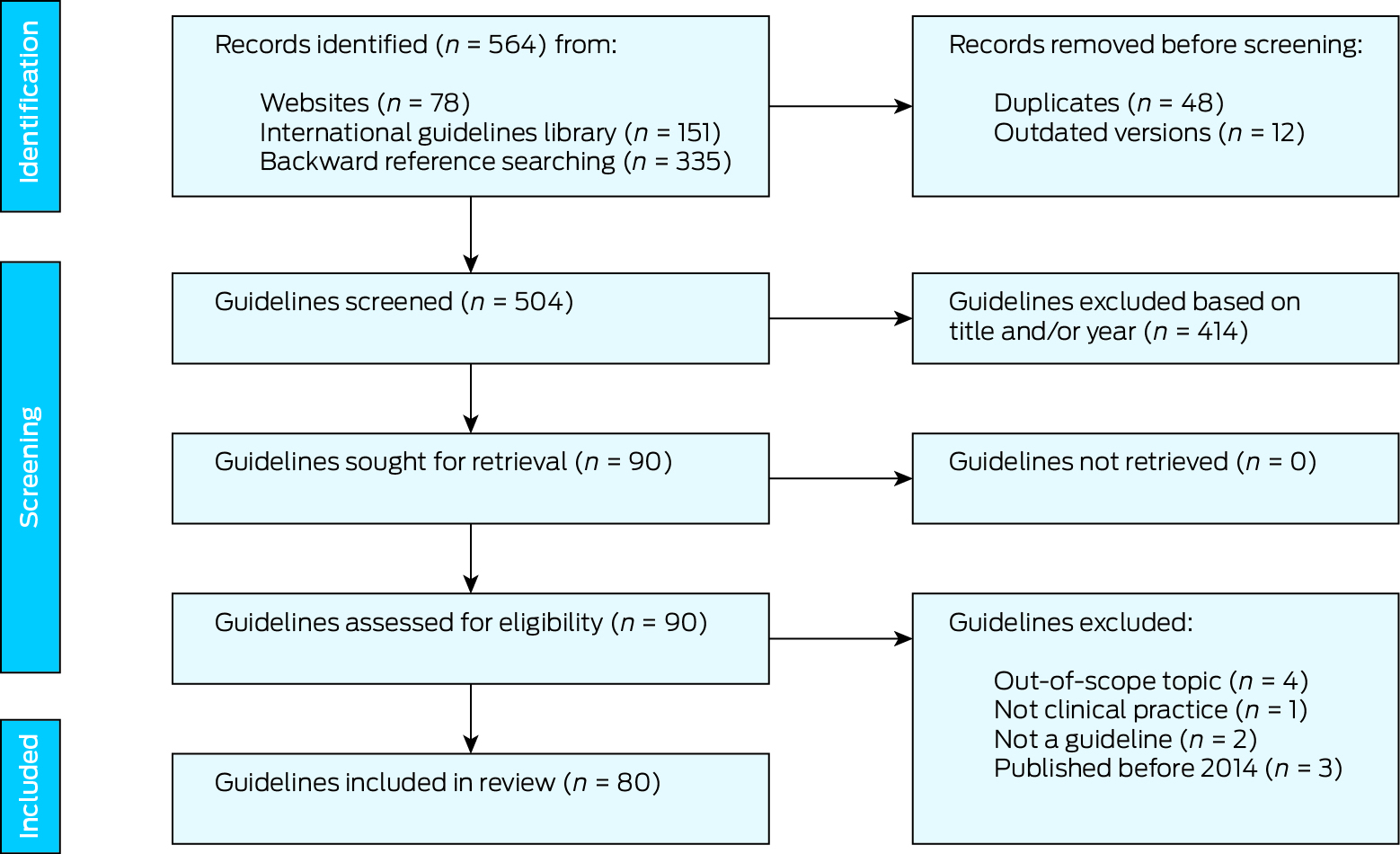

Guideline selection

We searched the Guidelines International Network international guidelines library, limiting the search to Australia as the country of application, and conducted a Google search with the keywords “clinical guidelines” and “Australia”. We also searched the websites of organisations likely to have relevant guidelines (eg, the NHMRC, health care professional colleges, universities, federal and state governments, associations, societies, foundations, and non‐government organisations). In addition, we searched the list of over 400 Australian clinical guidelines identified by authors who had access to the now‐defunct NHMRC guideline database.20 Furthermore, we sought a representative example of guidelines from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (in theory, dealing only with women's health) and from the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand (which deals predominantly with men's health) so as not to skew for sex‐specific guidelines.

The eligibility criteria were that the document:

- provided explicit guidance for clinical care;

- was published between 1 January 2014 and 31 April 2024;

- was the most recent version; and

- employed Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) methods or similar, or was endorsed, approved or acknowledged (such as by a logo) by the NHMRC or another major national body, or concerned marginalised groups.

Because, we suggest, no clinical care should ignore the significance of sex and gender, we did not exclude any guideline topic as irrelevant to matters of sex and gender. Gender awareness, in particular, can be overlooked despite the need to consider circumstances in, for example, social determinants of health and a person's capacity to manage prescribed care, given their gender identity and its role in domestic and family life.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extracted from the clinical guidelines were the use of the terms “sex”, “gender”, “female”, “male”, “women”, “men”, “girl” and “boy”, and the incorporation of sex‐ and gender‐relevant guidance. If none of these terms were identified, we also searched for “psychosocial” and “cultural”. We recorded whether guideline developers had used a method such as GRADE, and which organisations had approved, endorsed or acknowledged the guidelines (such as by a logo). We accepted as implicit approval the publication of a document by an organisation. The text surrounding any relevant identified terms was searched for context and meaning, including relevance to clinical practice. Data extraction was cross‐checked by two of us (MK, TH). Decisions were discussed within the research team until consensus was reached.

Guideline developers assess the quality of evidence in references that they cite. We did not conduct further quality assessment of guidelines because we sought only to identify the inclusion of sex and gender in each guideline.

Ethics approval

We did not require ethics approval for this study as it was an analysis of publicly available documents.

Results

Eighty eligible guidelines were identified (Box 1). They covered 27 areas of practice, from Aboriginal health to thoracic medicine, with 21 related to general practice, nine to oncology, and seven to cardiology. The guidelines were developed and hosted by 51 organisations: colleges, societies, associations, foundations, non‐government organisations, federal and state governments, and expert groups in universities. We selected one representative guideline from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the Endometriosis clinical practice guideline (2021).23 We were not able to carry out the plan with the Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand because their website24 directed visitors to the European Association of Urology for their guidelines, which were not within our eligibility criteria. The few Australian guidelines on their website were on topics such as working within coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) lockdown restrictions and performing circumcision on infant males; these were either ineligible (COVID‐19 lockdowns no longer apply) or too specific to male health.

Of the 80 documents that we surveyed, two‐thirds (n = 52) were called guidelines, eight were referred to as guides, three as statements, three as handbooks, and one each as a standard, a clinical update, recommendations, clinical guiding principles, inclusive health care, or a clinical governance framework. A further eight documents specified the disease or condition with “management”. Details of all the guidelines are provided in the Supporting Information.

Guidelines drew on heterogeneous research, some of which provided no sex‐disaggregated data. Our analysis revealed varied levels of inclusiveness in dealing with sex and gender matters in health care, with most guidelines being at the lower end of the inclusiveness scale. None of the terms “sex”, “gender”, “women”, “men”, “female”, “male”, “girl” or “boy” were found in 12 of the guidelines, including guidelines from the Australasian College of Dermatologists, the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, Children's Health Queensland and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (on e‐mental health). The majority of the remainder used some of these terms only a few times, with 34 guidelines employing “gender” to mean “sex”. The terms “sex” and “gender” were defined to some extent in only four guidelines, from the Australian Institute of Sport (in their guideline on concussion and brain health), the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health and General Practice Supervision Australia. The Autism Cooperative Research Centre defined gender identity for transgender people while also using “sex” and “gender” interchangeably. Kidney Health Australia, while not using the terms “sex” or “gender”, referred to care of “women and people with uteruses”, indicating sensitivity to the complexities of sex and gender. The Australian Institute of Sport noted the lack of evidence on gender; this organisation not only presented definitions of “sex” and “gender” but also used the terms consistently.

There was no reference to clinical practice concerning sex in 15 of the guidelines, including guidelines from the National Heart Foundation of Australia, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (on the management of hyperglycaemia) and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists. The 65 guidelines that did incorporate matters relevant to sex presented varied degrees of information, from a single statement about prevalence to details about risk factors, prevalence, treatment and management. Guidelines with detailed information about sex‐relevant practice included guidelines from Ambulance Victoria, the Australian Diabetes Society, the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, General Practice Supervision Australia and the Monash University Guideline Development Group.

The majority of the 80 guidelines — 46 of them — made no mention of clinical practice concerning gender. Only 12 developed ideas of gender in any detail, including discussion of topics such as gender inequality, transgender and intersectionality. The remaining 22 either implied aspects of gender awareness without stating this or mentioned “psychosocial” or “cultural” considerations that could relate to gender, demonstrating at least awareness of the contexts within which people live. Examples of organisations with guidelines explicitly incorporating gender awareness are the Australasian Sexual and Reproductive Health Alliance, the Australian Professional Association for Trans Health, the Centre of Perinatal Excellence, General Practice Supervision Australia, the Living Evidence for Australian Pregnancy and Postnatal Care Guidelines Group and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (in relation to preventive care, and to violence and abuse). Examples of gender and sex information and guidance identified in guidelines are provided in Box 2.

Discussion

We found variations in the extent to which evidence on sex and gender is incorporated in Australian clinical practice guidelines. The terms “sex” and “gender” tended to be used interchangeably or conflated, and were rarely defined. Of 80 guidelines, 12 used none of these terms, while another 12 referred substantively to gender disparities and considerations. Only one guideline noted a lack of gender‐based evidence. These results are consistent with what was found in a review of 118 Canadian guidelines, including identification of keywords in only two‐thirds of the guidelines and correct use of “sex” and “gender” in only one‐third;18 we were unable to locate similar completed research elsewhere.

The authors who reviewed the Canadian guidelines suggested several reasons for the limited attention paid to sex and gender and disaggregated evidence in clinical guidelines.18 First, there is limited research on sex and gender differences in medicine. Most biomedical experiments have, in the past, been exclusively conducted on male animals, there is substantial under‐representation of women in clinical trials, and many sex and gender differences are yet to be recognised. Second, while there are increasing numbers of medical publications considering women and men separately, less than a quarter present differences in management decisions for patients based on sex or gender. Third, currently available guideline development instruments do not provide instructions for synthesising sex and gender evidence. Although the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II document25 and the GRADE framework26 require the specification of populations in systematic reviews, they do not require details of evidence particular to women and men nor any statement about sex or gender differences. Unless clinical practice guideline working groups specifically raise questions about evidence‐based sex and gender differences, it is unlikely that the correct search terms will be used to interrogate the literature.18

Limitations

Unlike published research articles, guidelines do not reliably appear in databases and are thus not amenable to standard systematic review search methods. Our search for guidelines was extensive but relied on supplementary search approaches (searches of the Guidelines International Network international guidelines library, Google and organisation websites) rather than traditional database searches. However, we sought to minimise any risk of missing eligible guidelines by drawing on a collection of 400 Australian guidelines identified in a recent survey.20

Although it is important for all guidelines to interrogate the evidence for data on sex and gender — because no health system can provide equitable care by ignoring the significance of either — we acknowledge that future research might consider the relevance of sex and gender to various conditions and disciplines. It was beyond the scope of this project to assess evidence for data on sex and gender that was used to develop guidelines. However, we caution that an assumption that sex and gender are less relevant to, for example, ophthalmology and dermatology than to sexual health may arise from a failure of knowledge and imagination. That some conditions and disciplines have obvious, overt implications for sex and gender should not blind us to the implicit, less obvious implications.

Conclusion

Given the significant role of clinical guidelines in shaping evidence‐based health care, it is imperative that they are designed to mitigate rather than reproduce sex and gender discrimination, whether that be towards women and girls or towards those who are sex and gender diverse. Although guidelines are built on existing evidence, such evidence should be assessed for the ways in which it deals with sex and gender. Standardised, equitable and evidence‐based rules for health care have the potential to reduce implicit bias that affects health care. Clinical guidelines are considered to be living rather than fixed documents, emphasising the need for health care professionals and researchers to be reflexive about their practice. When developing or updating guidelines, we recommend that the members of committees and working groups, colleges, and other relevant organisations make a concerted effort to include sex‐ and gender‐related matters relevant to the identification, appraisal and description of evidence. We also recommend that a statement about lack of sex‐ or gender‐specific evidence should be the minimum requirement for clinical practice guidelines. A process of collaborative co‐design rather than individual or fragmented actions is imperative to the implementation of this approach. In addition, we recommend that clinical guideline development bodies develop transparent policies for increasing the participation of women and gender‐diverse people in guideline development panels. Finally, guideline development instruments, such as AGREE II and GRADE, need to include instructions for synthesising sex and gender evidence.

Box 2 – Examples of clinical practice guidelines and their inclusion of sex‐ and gender‐relevant material*

|

Extent of guidance provided |

Condition or population |

Sponsoring organisation |

Use of gender‐ or sex‐specific language |

Guidance on sex‐ or gender‐relevant practice |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Detailed: sex‐relevant practice (of a total of 41 guidelines) and/or gender‐relevant practice (of a total of 12 guidelines) |

Advanced life support |

Ambulance Victoria |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Cardiovascular disease risk |

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

LGBTQIA+ health and inclusive health care in general practice |

General Practice Supervision Australia |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Abuse and violence |

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Minimal: sex and gender terms (of a total of 16 guidelines); sex‐relevant care (of a total of 24 guidelines); and gender‐relevant care (of a total of 22 guidelines) |

Liver disease |

Australasian Hepatology Association |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Lung cancer |

Cancer Council Australia |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Chronic kidney disease |

Kidney Health Australia |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Atrial fibrillation |

National Heart Foundation of Australia |

|

|

||||||||||||

|

None (of a total of 12 guidelines) |

Anaesthesia |

Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Emergency management of ketoacidosis and hyperglycaemia |

Children's Health Queensland |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Acute coronary syndrome |

National Heart Foundation of Australia |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

E‐mental health |

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners |

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

LGBTQIA+ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual and other non‐heteronormative or non‐binary sexual and gender identity. * Details of all the guidelines are provided in the Supporting Information. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 14 August 2024, accepted 13 January 2025

- Maggie Kirkman1

- Tomoko Honda1

- Steve J McDonald1,2

- Sally Green1

- Karen Walker‐Bone1

- Ingrid Winship3

- Jane R W Fisher1

- 1 Monash University, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Cochrane Australia, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Melbourne Health, Melbourne, VIC

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data Sharing:

This article includes no original data.

This research was funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Jane Fisher is supported by a Finkel Professorial Fellowship, which is funded by the Finkel Family Foundation. The Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care commissioned the research of which this manuscript forms a part. They have given permission to publish. The Finkel Family Foundation had no role in the work.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Asiskovitch S. Gender and health outcomes: the impact of healthcare systems and their financing on life expectancies of women and men. Soc Sci Med 2010; 70: 886‐895.

- 2. World Health Organization. Gender and health. https://www.who.int/health‐topics/gender#tab=tab_1 (viewed July 2024).

- 3. Lyszczarz B. Gender bias and sex‐based differences in health care efficiency in Polish regions. Int J Equity Health 2017; 16: 8.

- 4. Riggs DW, Coleman K, Due C. Healthcare experiences of gender diverse Australians: a mixed‐methods, self‐report survey. BMC Public Health 2014; 14: 230.

- 5. Fisher J, Makleff S. Advances in gender‐transformative approaches to health promotion. Ann Rev Public Health 2022; 43: 1‐17.

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standard for sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation variables. Canberra: ABS, 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/standard‐sex‐gender‐variations‐sex‐characteristics‐and‐sexual‐orientation‐variables/latest‐release (viewed July 2024).

- 7. Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting sex, gender, or both in clinical research? JAMA 2016; 316: 1863‐1864.

- 8. The Sex and Gender Sensitive Research Call to Action Group; Wainer Z, Carcel C, Hickey M, et al. Sex and gender in health research: updating policy to reflect evidence. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 57‐62.e1. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/2/sex‐and‐gender‐health‐research‐updating‐policy‐reflect‐evidence

- 9. Pinn VW. Sex and gender factors in medical studies: implications for health and clinical practice. JAMA 2003; 289: 397‐400.

- 10. Plevkova J, Brozmanova M, Harsanyiova J, et al. Various aspects of sex and gender bias in biomedical research. Physiol Res 2020; 69: s367‐s378.

- 11. Office of Research on Women's Health (National Institutes of Health). NIH Inclusion Outreach Toolkit: how to engage, recruit, and retain women in clinical research. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/toolkit/recruitment/history (viewed July 2024).

- 12. National Health and Medical Research Council. Statement on sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation in health and medical research. Canberra: NHMRC, 2024. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/research‐policy/gender‐equity/statement‐sex‐and‐gender‐health‐and‐medical‐research (viewed July 2024).

- 13. Heise L, Greene ME, Opper N, et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet 2019; 393: 2440‐2454.

- 14. Antequera A, Cuadrado‐Conde MA, Roy‐Vallejo E, et al. Lack of sex‐related analysis and reporting in Cochrane Reviews: a cross‐sectional study. Syst Rev 2022; 11: 281.

- 15. Barlek MH, Rouan JR, Wyatt TG, et al. The persistence of sex bias in high‐impact clinical research. J Surg Res 2022; 278: 364‐374.

- 16. Hallam L, Vassallo A, Hallam C, et al. Sex and gender reporting in Australian health and medical research publications. Aust N Z J Public Health 2023; 47: 100005.

- 17. National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines (viewed July 2024).

- 18. Tannenbaum C, Clow B, Haworth‐Brockman M, et al. Sex and gender considerations in Canadian clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. CMAJ Open 2017; 5: E66‐E73.

- 19. Naghipour A, Gemander M, Becher E, et al. Consideration of sex and gender in European clinical practice guidelines in internal medicine: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e071388.

- 20. Shalit A, Vallely L, Nguyen R, et al. The representation of women on Australian clinical practice guideline panels, 2010–2020. Med J Aust 2023; 218: 84‐88. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/2/representation‐women‐australian‐clinical‐practice‐guideline‐panels‐2010‐2020

- 21. Kirkman M, Honda T, Fisher J, et al. Literature review to inform strategies to address sex and gender bias in the health system. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2025. www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/literature‐review‐to‐inform‐strategies‐to‐address‐sex‐and‐gender‐bias‐in‐the‐health‐system (In press).

- 22. Commonwealth of Australia; Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Working for women: a strategy to achieve gender equality. March 2024. https://genderequality.gov.au/ (viewed July 2024).

- 23. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Endometriosis clinical practice guideline 2021. https://ranzcog.edu.au/resources/endometriosis‐clinical‐practice‐guideline (viewed Jan 2025).

- 24. Urological Society of Australia and New Zealand. Position statements and guidelines. https://www.usanz.org.au/info‐resources/position‐statements‐guidelines (viewed Apr 2024).

- 25. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010; 182: E839‐E842.

- 26. Siemieniuk R, Guyatt G. What is GRADE? BMJ Best Practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/us/toolkit/learn‐ebm/what‐is‐grade (viewed July 2024).

Abstract

Objective: To assess Australian clinical guidelines for their inclusion of sex and gender.

Design, setting: Survey of all clinical guidelines published in Australia from 1 January 2014 to 31 April 2024 that employed methods such as Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations, or were endorsed, approved or acknowledged by the National Health and Medical Research Council or another major national body, or concerned marginalised groups.

Main outcome measures: Use of the terms “sex”, “gender”, “female”, “male”, “women”, “men”, “girl” and “boy”; definitions of “sex” and “gender”; and incorporation of sex‐ and gender‐relevant guidance.

Results: The 80 eligible guidelines were from 51 organisations and covered 27 areas of practice. No sex‐ or gender‐related terms were found in 12 of the guidelines. Of the remaining 68 guidelines, most used some of these terms only a few times, with 34 of them using “gender” to mean “sex”. “Sex” and “gender” were defined to some extent in four guidelines. There was no reference to clinical practice concerning sex in 15 of the guidelines. A total of 46 guidelines made no mention of clinical practice concerning gender, only 12 included gender‐relevant practice in any detail, and the remaining 22 either implied aspects of gender awareness without stating this or mentioned “psychosocial” or “cultural” considerations. Guidelines drew on heterogeneous research, some of which provided no sex‐disaggregated data.

Conclusions: Guideline development bodies should be encouraged to assess evidence for its treatment of sex and gender, to enable strategies to counter inequity and discrimination.