First Nations people experience high levels of chronic disease, resulting from a history of colonisation, institutional racism and policies that have disempowered participation in practices that would otherwise support health and wellbeing.1,2 In addition, First Nations people living in remote areas have limited access to primary and specialist care, hospital and pathology services and reduced infrastructure.3,4 These factors contribute to infectious diseases having a disproportionately greater impact on First Nations people living in remote areas compared with urban settings.4,5 Funded by the Australian Government and with First Nations-led governance, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander COVID-19 Point-of-Care Testing Program (hereafter referred to as the program) was implemented in early 2020. Testing was conducted by primary care clinicians using the GeneXpert assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2, Cepheid) enabling increased access to molecular-based testing, and therefore quicker results. The program rapidly became the world's largest decentralised SARS-CoV-2 molecular point-of-care (POC) testing network.6 The program was delivered across three distinct epidemiological phases of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in Australia, each with associated public health responses (Box 1).

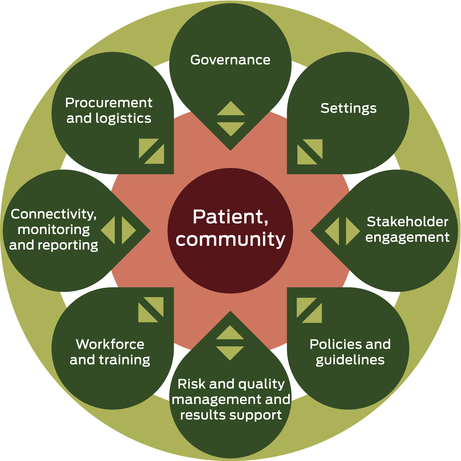

To inform future infectious disease pandemic preparedness and responses, we used an adapted POC testing framework,6 based on the World Health Organization health system building blocks7 to systematically review program documents, including standard operating procedures, internal team communications, and formal program updates to partners. The review process identified, collated and documented key recommendations. Box 2 shows the updated framework, which now includes workforce and training, results support, and reflects an enhanced focus on the community as central to program effectiveness.

Governance

The success of the COVID-19 response in First Nations communities in Australia is attributed to engagement and leadership by First Nations people.8,9 The program was overseen by the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Protection subcommittee (formerly the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Advisory Group on COVID-19) of the Australian Health Protection Committee.10 This group was made up of representatives from Aboriginal community-controlled health services, other First Nations experts and government; and was responsible for the co-design and oversight of the program, and final approval of protocols, expansions and allocation of testing resources. Consistent with National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council (NPAAC) guidelines on POC testing,11 the program ensured a model of clinical governance through a clinical advisory group with expertise in virology, infectious diseases, and First Nations remote clinical practice. The expertise of this group proved invaluable in ensuring the POC testing systems were tailored appropriately to First Nations-led health services. The governance model was later modified, retaining the First Nations governance with a dedicated First Nations leaders group, complemented with a formal clinical POC testing governance model led by a virologist. A multidisciplinary operational team consisting of medical laboratory scientists, public health epidemiologists, information technology specialists, logisticians, clinicians, POC testing experts and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers ensured a responsive and adaptable program network.

Patient and community

Maintaining the patient and community as central to the program framework was fundamental to its effectiveness and is a key difference compared with other frameworks in infectious disease diagnostic testing.12,13 Each health service integrated molecular POC testing in ways that met community needs and staff capacity. Approaches included regular testing of clinical staff to minimise furloughing, thereby keeping the service open during peak community outbreaks and having a dedicated POC operator during high demand periods. Health services led communications regarding the availability of the molecular POC testing in their community.

From April 2020 to August 2022, health services conducted 72 624 SARS-CoV-2 patient POC tests (average of 596 tests per week).14 Most tests (67.1%) were conducted in First Nations peoples,15 with limited testing conducted in non-Indigenous people (clinical staff or other frontline workers). This proportion of testing in First Nations peoples increased from 65.3% in Phase 1 to 75.3% in Phase 3, suggesting more targeted testing once community transmission was established.14 Program data facilitated support to services to ensure targeted testing occurred, particularly during periods of limited testing resources. The test positivity rate per 100 tests, by jurisdiction, has been described elsewhere.15

Molecular POC testing detected the first positive cases in most communities (Box 3), leading to rapid responses from health service staff in partnership with visiting public health teams within 0–1 day following case detection (unpublished data from public health departments and Aboriginal community-controlled health organisations across three jurisdictions with the highest number of participating services).

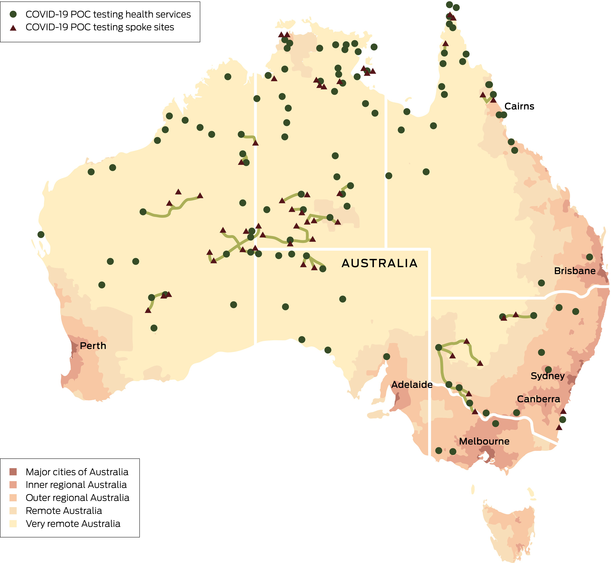

Setting

As of 31 August 2022, 105 clinics (government-managed or community-controlled) were enrolled in the program.15 Most clinics were in very remote (66%) and remote areas (12%) (Box 4) across six jurisdictions. Communities ranged in size from 80 to over 9000 First Nations people. The initial site selection criteria6 evolved with each epidemiological phase, with greater demand for additional clinic enrolment where existing laboratory capacity was exceeded. Hub and spoke models, with molecular POC testing at a larger clinic and the ability to provide test results to nearby smaller communities, were effective only in a limited number of settings as the increased demand on staff time for transportation of samples became unfeasible.

The median aerial distance from participating health services to the nearest laboratory that offered molecular SARS-CoV-2 testing was 569 km (interquartile range [IQR], 351–1128 km), with the average driving time about 8 hours. Some services endured additional accessibility challenges, such as services on remote islands or where road travel was disrupted by monsoonal conditions. Most (90%) services were in areas considered to be among the most disadvantaged nationally (based on the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas deciles 1–3).16 Three services withdrew from the program (up to August 2022) indicating workforce constraints and/or waning perceived benefit as pandemic risk abated.

Policies and guidelines

Across all phases, the program ensured that operating procedures were consistent with relevant national laboratory guidelines, and regulatory frameworks for POC testing.11,17,18 Following the availability of rapid antigen tests (RATs) (November 2021), the program (in consultation with the clinical advisory group and jurisdictional partners) provided guidance on appropriate use of molecular POC testing (Box 5). Considering the lower sensitivity and thus higher false-negative result rate with RATs compared with molecular POC tests (particularly in early or asymptomatic infection),19,20 solely relying on RATs to detect the first cases in a community would have led to substantial delays in individual and public health responses.

Stakeholder engagement

The program team participated in intensive stakeholder engagement to target support and identify high risk community events, including COVID-19 cases detected in other communities with known community links, and wastewater surveillance detections. This approach enabled the program to respond quickly to changing demand, identify optimal transport routes, coordinate local consumable surge supply storage, and deploy additional or new testing equipment to locations where outbreaks were expected (Box 6).

Program engagement with pathology providers ensured complementary and equitable testing coverage, enhanced capacity where needed, and identified appropriate referral testing pathways. The program became an important source of bidirectional communication to alert health services, public health, reference laboratories and government regarding first cases in remote communities. Following the first outbreak in a remote area, the program disseminated key lessons learnt with stakeholders across the network that were yet to experience an outbreak to assist community preparation.

Risk and quality management framework and results support

The program's risk and quality management framework was developed in accordance with the NPAAC requirements for POC testing in Australia and included risk assessment and mitigation, POC operator training and competency assessment, quality control and external quality assurance.6 This framework was continuously enhanced in response to the changing epidemiology (Box 7).

Workforce and training

As of the end of August 2022, 908 clinic staff (nurse, Aboriginal health practitioner or doctor) had completed theoretical training and practical competency assessments.15 Following the increase in COVID-19 cases (Phases 2 and 3), additional focus was placed on potential risk for contamination, waste disposal, infection prevention and control during the testing process, including environmental monitoring and decontamination procedures and device/equipment maintenance.

Existing constrained staff capacity in remote health services was further exacerbated by the pandemic travel restrictions.23 Staff capacity was often identified as a key factor for testing errors, highlighting the need for a dedicated, sustainably funded, POC test operator workforce model and scientific support services going forward. During peaks in testing demand (Phases 2 and 3), the program (in consultation with the clinical advisory group) provided evidence-based, epidemiologically guided support to staff to prioritise molecular POC testing to balance workload demands, community expectations and maintain test quality.

Connectivity, monitoring and reporting

The program connectivity system6,24 was optimised to strengthen the reliability and timeliness of results delivery, including automated email alerts and middleware upgrades to enable more streamlined identification and rectification of connectivity disruptions and support changes to testing guidelines, results management and compatibility with co-implemented proprietary testing software (GxDx, Cepheid).

The median transmission time for test results to end-user databases (calculated from the start of test to receipt by recipient, inclusive of test run time of 45 minutes) was 1.4 hours (IQR, 0.95–2.4 hours) in 2021.24 Considering the receipt of a centralised pathology result for samples collected in remote communities routinely takes 4–6 days (longer in outbreak periods), the 72 624 patient tests conducted at the POC testing sites equated to 17 564 days saved in receiving positive SARS-CoV-2 test results (calculation based on 4391 positive test results15 and the four-day minimum result turnaround time from centralised laboratories within the study period).

All six jurisdictions were supplied with test results in a manner that satisfied mandatory case notification requirements for public health surveillance, representing the first large decentralised POC testing network of its kind in Australia to satisfy this requirement.

Procurement and logistics

Procurement and access to test cartridges was coordinated nationally by the Australian Government. The program received a third of all cartridges available nationally each week — above the population proportional allocation — accounting for the specific risks associated with higher levels of chronic disease and lack of timely testing alternatives in remote communities. Despite this, demand exceeded supply during Phases 1 and 2, until RATs became available during Phase 3.

The program used an agile supply management system to ensure adequate stocks across the network, particularly in locations often cut off from regular supply routes due to COVID-19 border closures or seasonal weather. Key adaptations to enhance the system included: (i) the establishment of an electronic alert system to identify low clinic stock; (ii) engagement with services to pre-empt increased test demand; (iii) collaboration with pathology providers to ensure adequate testing coverage; and (iv) stock expiry management.

Conclusion

There was an early and justifiable recognition in Australia that COVID-19 public health responses needed to prioritise and tailor strategies for remote areas to ensure equitable access to health and other support services for First Nations peoples. In Australia, this translated to significant action through the implementation of service-led, decentralised COVID-19 molecular POC testing, which became part of a comprehensive, responsive and integrated public health response.

Decentralised molecular POC testing embedded into primary health services was an integral component of Australia's COVID-19 outbreak response in First Nations communities and if sustained, will provide key preparedness infrastructure to respond to future pandemics.

Fundamental recommendations are summarised in Box 8. We acknowledge the limitations of these recommendations as they were generated through the lens of program staff, and therefore may contain some biases. However, as these staff were involved in the implementation of this program over the entirety of the pandemic response, this perspective provides a unique insight that warrants reporting.

Future directions

The established relationships, First Nations people-led governance, decentralised asset network and infrastructure provide the opportunity to evaluate, implement and scale up POC testing for other priority infections in these communities (including influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, sexually transmitted infections, hepatitis C, human papillomavirus and group A Streptococcus), and serves as a model for future emergency responses for infectious diseases with epidemic potential. Going forward, establishing sustainable funding models to support all facets of the program (Box 2) will be critical to the wider adoption of decentralised molecular testing in Australia and other settings.

Box 1 – Remote Australian epidemiological phases of COVID-19 (April 2020 to August 2022)

|

Epidemiological phase |

Definition |

Time period |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Phase 1 |

From the beginning of the First Nations COVID-19 Molecular Point-of-care Testing Program (program) until first cases of community transmission |

April 2020 – July 2021 |

|||||||||||||

|

Phase 2 |

Established community transmission in two jurisdictions |

August 2021 – December 2021 |

|||||||||||||

|

Phase 3 |

Established transmission nationally (evidenced throughout the program). |

January 2022 – August 2022 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Updated COVID-19 point-of-care testing framework6

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019. Source: adapted from The Lancet Infectious Diseases with permission.6

Box 3 – Case study 1: prompt response, site support and stakeholder engagement

Late in Phase 2, the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in a remote community was detected by the First Nations COVID-19 Molecular Point-of-care Testing Program (program). This individual had recently travelled to the community from a nearby regional town. The individual tested positive via molecular point-of-care (POC) testing, the POC operator notified the result directly to the regional public health department, with a formal result from the program following promptly. Within 24 hours of the positive result, a public health team flew into the community to collect samples to be sent back to the reference laboratory, or if the result was urgent due to the individual being unable to isolate or being at risk of severe illness, the sample was tested on the molecular POC device within the primary care service. Following this, program staff became aware of individuals who had recently travelled from this community into another jurisdiction and who were being followed up with contact tracing. Program staff contacted the relevant health service to ensure adequate staff testing capacity, offer further training and send additional testing equipment. Alongside this, program staff were also in contact with the jurisdictional pathology providers to ensure a comprehensive and complementary response was conducted.Box 4 – Map of participating health services

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; POC = point-of-care.

Box 5 – Recommended COVID-19 point-of-care test use in remote communities in Australia

|

Level of COVID-19 community transmission |

Recommended COVID-19 POC test type |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

No known community transmission |

Molecular POC test for both asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals. |

||||||||||||||

|

Established community transmission |

RATs for both symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals, unless:

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; POC = point-of-care; RAT = rapid antigen test. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Case study 2: point-of-care operator support and bidirectional communication

Early in Phase 2, a remote community experienced their first outbreak of community transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The resulting impact on the health services included point-of-care (POC) operators working extended hours, well beyond a usual working day and including weekends to conduct POC testing; POC testing demand was further increased as a result of visiting public health teams collecting additional samples throughout the community and pathology-based testing was severely constrained, resulting in delayed results. The First Nations COVID-19 Molecular Point-of-care Testing Program's hotline staff were in constant contact with the POC operators conducting testing within the clinics, while other program staff were urgently liaising with regional public health, pathology departments and the Australian Government to support equitable testing approaches. Through this bidirectional communication, further molecular POC testing resources were deployed to enhance capacity within existing participating services, and new services enrolled where community transmission was next expected or just commencing. Further, to support the POC operators at services experiencing very high demand, POC testing prioritisation guidelines were developed, and additional staff trained.Box 7 – Program quality and risk management enhancements

|

Category |

Process |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Positive patient test results |

Electronic alert to program staff if:

|

||||||||||||||

|

High cycle threshold results* |

High cycle threshold results triggered intensive review by program staff in partnership with the health service, responsible public health team and reference laboratories (called “case investigations”) — consistent with guidance from Australia's peak laboratory advisory organisation (Public Health Laboratory Network). |

||||||||||||||

|

Quality control |

In response to an increased number of positive test results, to ensure accuracy of results and device performance, the frequency of negative quality control, and/or blank molecular transport media testing was altered. |

||||||||||||||

|

Variants of concern |

Inclusion of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in external quality assurance material was conducted where available through the external quality assurance provider (RCPAQAP). |

||||||||||||||

|

Risk of contamination |

POC operator re-training with specific focus on minimising the risk of biological and/or amplicon contamination. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

POC = point-of-care; Program = First Nations COVID-19 Molecular Point-of-care Testing Program; RCPAQAP = The Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Quality Assurance Program; SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. *The SARS-CoV-2 GeneXpert assay is highly sensitive, and false-positive results related to high cycle thresholds have been reported, albeit infrequently.22 To minimise the risk of unnecessary public health responses following false-positive results, results with “high” cycle threshold values (> 35) were agreed to be referred to as “non-negatives” during Phase 1. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 8 – Summary recommendations by point-of-care testing framework component

|

POC testing framework component |

Recommendation |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Governance |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Patient and community |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Setting |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Policies and guidelines |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Stakeholder engagement |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Risk and quality management and results support |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Workforce and training |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Connectivity, monitoring and reporting |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Procurement and logistics |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; POC = point-of-care; Program = First Nations COVID-19 Molecular Point-of-care Testing Program. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Thurber KA, Barrett EM, Agostino J, et al. Risk of severe illness from COVID‐19 among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults: the construct of ‘vulnerable populations’ obscures the root causes of health inequities. Aust N Z J Public Health 2021; 45: 658‐663.

- 2. Sherwood J. Colonisation ‐ it's bad for your health: the context of Aboriginal health. Contemp Nurse 2013; 46: 28‐40.

- 3. Bailie RS, Wayte KJ. Housing and health in Indigenous communities: key issues for housing and health improvement in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Aust J Rural Health 2006; 14: 178‐183.

- 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote heath. Australian Government: AIHW, July 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural‐remote‐australians/rural‐and‐remote‐health (viewed Dec 2022).

- 5. Hengel B, Maher L, Garton L, et al. Reasons for delays in treatment of bacterial sexually transmissible infections in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia: a qualitative study of healthcentre staff. Sex Health 2015; 12: 341‐347.

- 6. Hengel B, Causer L, Matthews S, et al. A decentralised point‐of‐care testing model to address inequities in the COVID‐19 response. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21: e183‐e190.

- 7. World Health Organization. Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO's framework for action. Geneva: WHO, 2007. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/everybody‐s‐business‐‐‐‐strengthening‐health‐systems‐to‐improve‐health‐outcomes (viewed June 2020).

- 8. Stanley F, Langton M, Ward J, et al. Australian First Nations response to the pandemic: a dramatic reversal of the ‘gap’. J Paediatr Child Health 2021; 57: 1853‐1856.

- 9. Eades S, Eades F, McCaullay D, et al. Australia's First Nations’ response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; 396: 237‐238.

- 10. Australian Government. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Protection AHPPS Sub‐Committee. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, August 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/committees‐and‐groups/the‐national‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐protection‐ahppc‐sub‐committee (viewed Aug 2023).

- 11. National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council. National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council (NPAAC) Requirements for Point of Care Testing. 2nd ed. Australian Government Department of Health, 2021. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/resource‐library/requirements‐point‐care‐testing‐second‐edition‐2021 (viewed Aug 2023).

- 12. World Health Organization. Universal access to malaria diagnostic testing: an operational manual. Geneva: WHO, 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44657/9789241502092_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (viewed Aug 2023).

- 13. World Health Organization. WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis, Module 3: Diagnosis. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://tbksp.org/en/node/720 (viewed Aug 2023).

- 14. Respiratory Infection POCT. First Nations Respiratory Infection Molecular POCT Program Report May 2020 to March 2023. https://www.covid19poct.com.au/covid‐dashboard (viewed Sept 2024).

- 15. Department of Health and Aged Care, Nous Group. Evaluation of COVID‐19 point‐of‐care testing in remote and First Nations communities. Nous: Dec 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/evaluation‐of‐covid‐19‐point‐of‐care‐testing‐in‐remote‐and‐first‐nations‐communities‐0?language=en (viewed Sept 2024).

- 16. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio‐economic indexes for areas (SIEFA) 2021. Canberra: ABS, 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people‐and‐communities/socio‐economic‐indexes‐areas‐seifa‐australia/latest‐release#interactive‐maps (viewed Jan 2025).

- 17. Public Health Laboratory Network. PHLN guidance on laboratory testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 (the virus that causes COVID‐19). PHLN, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/01/phln‐guidance‐on‐laboratory‐testing‐for‐sars‐cov‐2‐the‐virus‐that‐causes‐covid‐19.pdf (viewed Apr 2020).

- 18. Commonwealth of Australia (Interim Australian Centre for Disease Control). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, version 8, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024‐06/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐cdna‐national‐guidelines‐for‐public‐health‐units_0.pdf (viewed Jan 2025).

- 19. Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Berhane S, et al. Rapid, point‐of‐care antigen and molecular‐based tests for diagnosis of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; 3: CD013705.

- 20. Fragkou PC, Moschopoulos CD, Dimopoulou D, et al. Performance of point‐of care molecular and antigen‐based tests for SARS‐CoV‐2: a living systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29: 291‐301.

- 21. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP). State Operations Manual, Appendix C ‐ Survey Procedures and Interpretive Guidelines for Laboratories and Laboratory Services. Baltimore: CMS, 1988. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations‐and‐Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/som107ap_c_lab.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 22. Falasca F, Sciandra I, Di Carlo D, et al. Detection of SARS‐COV N2 gene: very low amounts of viral RNA or false positive? J Clin Virol 2020; 133: 104660.

- 23. Fitts MS, Russell D, Mathew S, et al. Remote health service vulnerabilities and responses to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Aust J Rural Health 2020; 28: 613‐617.

- 24. Saha A, Andrewartha K, Badman SG, et al. Flexible and innovative connectivity solution to support national decentralised infectious diseases point‐of‐care testing programs in primary health services: descriptive evaluation study. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e46701.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

The First Nations Molecular Point of Care Testing Program is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. We thank the Australian Department of Health, Indigenous Health Branch for funding. They had no role in the design, preparation or publication of this manuscript. On behalf of all past and present program team members from the Kirby institute, including Rachel Papa, and the International Centre for Point‐of‐Care Testing, Flinders University; participating Aboriginal community‐controlled health organisations and peak bodies including: National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, Aboriginal Health Council of WA, Aboriginal Health Council of SA, Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of NSW, Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory, Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council, Apunipima Cape York Health Council, Ngaanyatjarra Health Service, Nganampa Health Council, Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services; industry partners including: Cepheid Inc, Clinical Universe, Health Link; state and territory health departments and other government services: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, VIC Health, WA Country Health Service, SA Health, NSW Health, QLD Health, NT Health; pathology providers: St Vincent's Centre for Applied Medical Research/NSW State Reference Laboratory for HIV, PathWest, Pathology Queensland, including Forensic and Scientific Services, SA Pathology, Territory Pathology, NSW Health Pathology, Peter Doherty Institute for Immunity and Infection, Microbiological Diagnostic Unit Public Health Laboratory & VIDRL, Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia Quality Assurance Program; governing bodies including: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Protection Sub‐committee, COVID‐19 Clinical Advisory Group, First Nations Infectious Diseases Point‐of Care Leaders Group.

Cepheid has contributed in‐kind study equipment (cartridges, machines) to the project Scaling up Infectious Disease Point‐of‐care Testing for Indigenous People (RARUR000080) funded by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) Rapid Applied Research Translation (RART) grant.