Participation is widely recognised as a determinant of children and young people's health.1 Both the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) (Article 18) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 12) enshrine participation as an inalienable right.2,3 Despite this, the exclusion and non‐participation of Indigenous children, adolescents and young people persists.4

Indigenous children and young people experience worse health outcomes than their non‐Indigenous peers and are starkly over‐represented in the contact with youth justice and in out‐of‐home care.5,6,7 We propose this is in part due to their exclusion and non‐participation — both as children and as Indigenous people.4,5,7 These children and young people's stories are often told for them, if at all.4 “It didn't matter what I screamed at (Child Protection Services), they wanted to tell my story for me, decide for me, know what was best for me. That's easier than listening, isn't it?”, said one Indigenous young person in contact with the youth justice system.6

Indigenous young people are less likely to access primary health services despite having more health needs than non‐Indigenous counterparts.8 Most children and young people in the youth justice system have severe neurodevelopmental disorders — nearly all previously undiagnosed and untreated.9 Current mainstream health and youth services are failing to provide culturally safe rudimentary services and meet Indigenous children and young people's unique needs.5,7,8,10 They have not been designed with meaningful participation of Indigenous people, let alone children and young people.5,8 There is an urgency for meaningful participation of Indigenous children and young people in reform.4,7,8 There is an urgency for decision makers to listen and act.4,5,7,8

Best‐practice mechanisms like the case study provided in this article, the Victorian based youth‐led, Indigenous‐led Koorie Youth Council, which centres self‐determination, can ensure that Indigenous children and young people are empowered.4 This article is part of the 2024 MJA supplement for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030, which examines how participating affects the health and wellbeing of children, young people and future generations. Society must not only uphold Indigenous children and young people's rights, but also value their strengths and the expertise they hold about their own lives.4,5,7,8,11

Participation is a spectrum

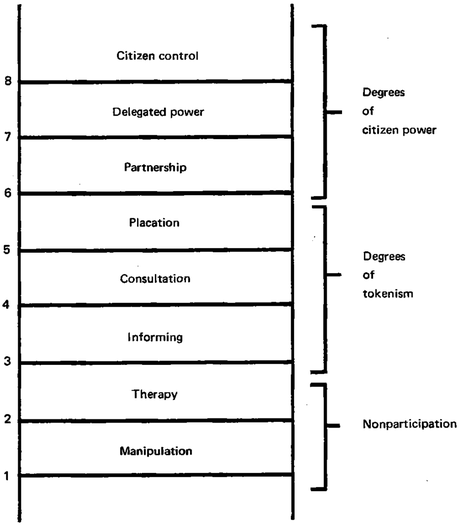

Participation is not a binary, it exists on a spectrum indicating the degree of agency afforded to individuals or groups to relationally determine outcomes.12,13 The degree of agency is the extent to which individuals can exercise freedom to determine their own outcomes, intersecting with the extent others exert power (and control) over them.14 Arnstein's ladder describes participation as ranging from manipulation to degrees of tokenism, through to citizen control or, in the language of UNDRIP, self‐determination (Box 1).2,12 In 1992, Hart adapted Arnstein's ladder of participation recognising adults as the relational power‐holders over children and young people.15 Developmentally, participation also allows children and young people the opportunity to practise agency, assess relational power dynamics, and invite others to participate in mutual causes.14,15

Participation is a determinant of Indigenous concepts of health

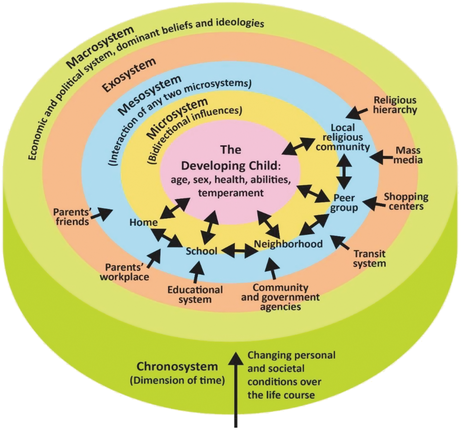

Indigenous concepts of health describe more than the physical status of an individual; they are collectivist and inclusive of “the social, emotional, and cultural wellbeing of the whole community”.16,17 Health exists not as a moment in time, but is a whole‐of‐life view.16 Indigenous concepts of health are intrinsically relational and include not just anthropocentric relationships to family, kin and community, but to history, Country, lands, spirituality and culture.17,18,19 Children and young people do not exist in isolation, but as Bronfenbrenner's ecological model describes, are influenced by the context around them (Box 2).20 Participation, or children and young people's relational agency across the ecological system, is a key determinant of Indigenous health.7,17

Although Bronfenbrenner's ecological system model provides a valuable conceptual framework for considering relational agency, it should also be acknowledged that it was developed with ontological and epistemological foundations insufficient to capture Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing. This is an unfortunate commonality among many mainstream youth social and health frameworks.16,21,22 They are often not cross‐culturally developed or tested, not fit for Indigenous contexts, and can inflict harm regardless of intent.21,22 In light of this, Māori academic Tuhiwai Smith challenges academics and clinicians to decolonise methodologies.21 An Indigenous critique of Bronfenbrenner's model includes that it is anthropocentric rather than chronocentric or ecocentric, and that it is focused on the individual rather than the collective.23

Fundamental concepts of childhood, and so age and developmentally appropriate participation, vary across different Indigenous cultures and often differ from Western norms.24 Supporting children and young people's participation and responsibility for kin, culture and lands is a value across many Indigenous cultures.16 Participation in community and cultural practices promotes Indigenous children and young people's positive sense of identity and culture and is also a determinant of Indigenous health.17,25,26 It is important to tailor participation strategies to meet the unique needs, development, cultural norms, obligations and preferences of individual children and young people.4

Koorie Youth Council: introduction to the case study

This article presents a case study of Koorie Youth Council (KYC) as an exemplary mechanism of young people's participation that centres self‐determination. It is both youth‐led and Indigenous‐led. KYC is the only organisation of its kind in Australia.27 It is the dedicated representative organisation for Indigenous young people living in Victoria towards the vision of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander young people collectively creating (their) future.

KYC was initially established in 2003 by the then Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission as the Victorian Indigenous Youth Advisory Council.27 KYC receives most of its funding through a combination of government grants and partnerships, currently operating under the auspices of the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service. KYC currently consists of an executive of 15 Indigenous young people and is staffed by nine young people, all Indigenous bar one. An all‐Indigenous board also provides strong cultural and governance support.

Five requisites for meaningful participation

We propose five requisites for meaningful participation. Both (i) visibility and (ii) inclusion are pre‐requisites of participation; that is, being considered and in the room, in the first place.28 Further, meaningful participation requires (iii) an acknowledgement of power dynamics (structural and relational); (iv) free, prior and informed consent; and (v) typically a shift of power.2,10,28,29

In the case of children and young people, it is important to recognise the complexities of free, prior and informed consent. Carers (kin in the case of kinship care, and non‐kin in many cases of out‐of‐home care) and, in some cases, the state act as a delegated authority that provides consent on behalf of children and young people.14,15 Free, prior and informed consent, a key principle in UNDRIP, ensures that participation is a choice free from coercion — the freedom to choose not to participate.2,28,29 Many Indigenous people would rather not participate than be restricted to tokenism. The spectrum of participation provides a salient example that the “how” for Indigenous people is as, if not more, important as the “what”.

Koorie Youth Council: Wayipunga participation framework

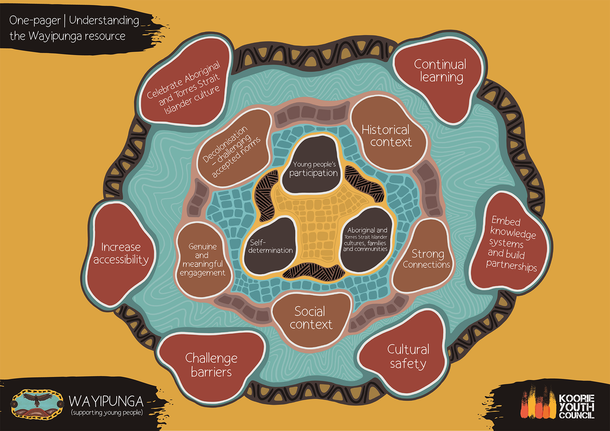

Wayipunga, meaning “supporting young people” in the Dja Dja Wurrung language, is a framework designed for workers, organisations and governments to facilitate culturally safe participation of Indigenous young people in decision‐making processes4 (Box 3). The resource was developed by KYC in response to the historical exclusion and non‐participation of Indigenous young people across services. It was informed by a series of Indigenous‐led, youth‐led workshops across Victoria to understand the needs, barriers and enablers of Indigenous young people's meaningful participation.

Wayipunga is structured around three sections: values, knowledge, and actions.4 Values lay the foundational principles on how to respect Indigenous young people.4 Knowledge provides the necessary insights for understanding their unique experiences and needs.4 Actions offers practical strategies to enhance meaningful youth participation and contribution.4 All three sections are interrelated and inform each other. Wayipunga challenges relational and structural power dynamics and reimagines accepted norms, centring Indigenous young people as experts on their own lives.

Participation based on need

Across youth and health services there has been increasing demand for participation by diverse cohorts, following recognition of failures for these populations.5 Many sectors have strived for population parity in Indigenous participation, but this neglects the disproportionate need for access to appropriate youth and health services. Indigenous children and young people have a higher likelihood of health burdens, including many diseases (such as trachoma, chronic suppurative otitis media and hearing loss, and rheumatic heart disease), developmental delay, death by suicide, and mental illness, as well as being over‐represented in at‐risk environments of out‐of‐home care and youth justice.7,8,30,31 This intersects with unique needs that require culturally informed support.4,5,7,8 The result is high demand for culturally safe clinicians, youth workers, and services.5,7,8 It is critical to acknowledge these indicators do not signal a problem with Indigenous children and young people, but rather stem from root historical and socio‐economic determinants of health and entrenched racism in colonial services and systems.5,8,10,32 Participation of intended users, particularly those with the greatest need and most barriers to access, should be prioritised in service design and reform.5,7,8

Koorie Youth Council: convening power to define unique needs

The Koorie Youth Summit, organised by KYC, is an annual event created for and by Indigenous young people.33 The summit is a vibrant environment for young people to connect, discuss significant issues, celebrate culture, and learn from one another. The summit emphasises cultural pride, strength and resilience, while also ensuring inclusivity and accessibility to those from regional and rural areas. These summits are also opportunities to define the unique needs of Indigenous young people, by Indigenous young people.

Koorie Youth Council: trusted peer services to support unique needs

The power shift and meaningful participation between government and the Indigenous community‐controlled sector was instrumental in the much lower coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) morbidity and mortality experienced by Indigenous Australians than expected (lower than non‐Indigenous Australians).34 Youth‐led services have a unique understanding of use and trends of language and current technology that can be harnessed for social mobilisation and health promotion.35,36 KYC demonstrated leadership during this time with increased frequency of its peer‐to‐peer virtual yarning circles (on Instagram) in response to the Victorian Indigenous community's expressed need. KYC's social media accounts encouraged Indigenous young people to engage in physical distancing and get vaccinated against COVID‐19 by appealing to Indigenous concepts of health, values and worldviews.

Racism contributes to poor health outcomes.10,37 Indigenous young people's high use of social media amplifies the experiences of racism.38 The failed 2023 Australian national referendum on enshrining an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in the constitution saw an increase in racism experienced by Indigenous Australians.39

A large proportion of the Indigenous population are children and young people; the median age of Indigenous people in Victoria is 24 years, compared with 38 years for non‐Indigenous Australians.40 With the voting age being 18 years, a large proportion of Indigenous Australians were disenfranchised during the 2023 Voice to Parliament referendum. They were not able to meaningfully participate in determining the outcome that most affects them, their families and communities. Although Australia permits young people aged 16 years to drive and be employed (and pay taxes), they have not been permitted meaningful participation in democratic elections.41 The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria has lowered the voting age to 16 years, mainstream Australia is yet to follow suit.42

During this tumultuous period, KYC continued yarning circles to support wellbeing. It is established that lack of cultural safety is a barrier for Indigenous young people accessing primary health and support services.8 Through social media, KYC encouraged young people to seek help from within the Indigenous community and/or culturally safe health and support services (such as Aboriginal Medical Services or crisis support phoneline 13‐YARN).

Seven red flags of performative non‐participation

Although tokenistic participation (informing, consultation, placation) does little to consider and redistribute power, non‐participation actively maintains the power imbalance.12 Non‐participation allows power holders to rubber‐stamp or tick a checkbox in a process, often with an intent to educate participants rather than listen to them.12 Frequently, even tokenistic participation is, in fact, performative non‐participation resembling instead manipulation or coercion.

The proposed seven red flags of performative non‐participation are that participation (i) is led by a non‐minority group (non‐Indigenous); (ii) is retrospective rather than prospective; (iii) is characterised by false urgency, without regard for the time it takes to build genuine relationships and trust; (iv) resembles informing rather than making space for dialogue; (v) is not representative of heterogeneity of minority (Indigenous) perspectives, prioritising or cherry‐picking the privileged, politically aligned, or least disruptive individuals; (vi) misses those with community‐recognised cultural authority; and/or (vii) where the priorities and outcomes are near or pre‐determined regardless.

Seven amber flags of tokenistic participation

Tokenism is common across organisations and not limited to the participation of Indigenous people. Arnstein's ladder posits informing, consultation and placation as forms of tokenistic participation as it maintains that, without accountability mechanisms, the power holders only heed the advice the powerful deem desirable and disregard what is less desirable.12 The proposed amber flags can indicate tokenistic participation. Amber flags require interrogation and often repair to move towards meaningful participation.

The proposed seven amber flags of tokenistic participation are: (i) use of buzzwords; (ii) employing a single person of the minority group; (iii) lacking an authorising environment (authority, resources or support); (iv) not valuing labour; (v) commodifying community connections and cultural knowledge; (vi) lacking culturally safe critical allies; and (vii) lacking mentorship, career progression and/or development.

Moving towards meaningful participation: amber to green

To improve the health and wellbeing of Indigenous children and young people, services, organisations and governments need to support the meaningful participation of Indigenous employees. All clinicians, researchers, leaders and decision makers can shift the amber flags of tokenistic participation towards meaningful participation in conjunction with the Wayipunga framework, considering the following seven items.

Interrogate language use

Use of buzzwords, such as “co‐design”, “place‐based” and “participatory research”, can elicit caution among minority groups and Indigenous people. While the intent of these concepts is to shift power, the language has been frequently co‐opted to rebrand lower levels of participation.43 For example, co‐design requires genuine partnership implying equal power; however, efforts labelled “co‐design” often fall short in redistributing any power.43 It can also be used as a convenient mechanism by power holders to take credit for when things go right and shift blame when things go wrong. Similarly, place‐based and participatory research have a wide range of interpretations depending on the stakeholder. These principles and their original intent (of shifting power towards community) should not be abandoned, but rather when the terms are used, continuous critical review between principles and practice is required.44

Recruit and retain power in numbers

Organisations may, with good intent, seek to diversify or establish meaningful participation of minority groups. However, these individuals are often pejoratively “the lonely only” — the only minority member within an organisation.45 Although the intent may be to increase the cross‐cultural capacity of the organisation, these employees typically have informal authority as an expert, but outsized organisational expectations often fall outside of their official, and often junior, role. Supporting and attracting cohorts creates solidarity in a shared experience, promotes change through political blocs, and acknowledges the heterogeneity of Indigenous perspectives, experiences and communities.46

Create authorising environments

Indigenous employees or participants commonly have not been equipped with an authorising environment (formal authority, resources, and/or support) to implement the organisation‐wide capacity uplift that is demanded from them.47 This often undermines their own and the organisation's success.47 Governance structures can help create accountability mechanisms for meaningful participation.48 This can be through ensuring that advisory and ethics boards are empowered with decision‐making capacity and ability to dissent.48 There should be zero tolerance for racism and harassment with well developed and adhered‐to workplace complaint policies. Improving overarching organisational diversity and leadership including at the hierarchical apex (organisational board members and executive), increases the likelihood of creating adaptive environments that are required for uplifting organisational cross‐cultural capacity.47

Value labour

Indigenous people are frequently expected to provide unpaid work, despite their subject matter expertise being recognised as crucial for improving organisation and government services.4,45 Like any expert, their time and contributions should be valued and remuneration normalised.49

Avoid commodifying community relationships and/or cultural knowledge

There is often expectation and/or coercion of Indigenous employees to engage in tokenistic participation, to answer but not ask questions, using their own cultural knowledge and community networks for the organisation rather than community's benefit. This commodification of relationships and cultural knowledge, the expectation to educate and connect their non‐Indigenous colleagues, including hierarchical superiors, can induce added strain to employment.50 This phenomenon is often termed “cultural load”; however, there is growing usage of “colonial load” instead, which reframes the source of the strain as not Indigenous cultures, but rather colonial foundations of non‐Indigenous‐led services, organisations, government and systems.50 Cultural safety is a journey not a destination.51 To reduce racism and inappropriate requests for education and connections, it is strongly recommended all organisations enshrine cultural safety training for all non‐Indigenous staff as an ongoing commitment.51

Provide culturally safe critical allyship

Shifting mainstream recognition regarding the value of lived experience, and the outsized health needs of Indigenous children and young people, has driven increased demand for participation of Indigenous people.5 This is a double‐edged sword: with increasing demand also comes increased burden.4 Despite increased demand in services, Indigenous people cannot be everywhere, all at once; they represent a small percentage of the Australian population, and carry social and cultural obligations that require time and attention.4 Strong extra‐ and intra‐organisational allies are required to progress work. Allyship is an often uncomfortable process of learning and unlearning. Critical allyship moves beyond intent and the interpersonal level to impact and the structural level.52 Critical allies hold a delicate tension between creating space and amplifying minority voices when able, while also thoughtfully lending their authority (own voice where it may be better heard or resources where needed), in the ultimate goal of structural change, without personal gain.52,53

Support mentorship, career progression and leadership development

Supporting and providing resources for mentorship, career progression, and leadership development throughout the lifespan is optimal practice, especially for Indigenous young people.4 Indigenous young people take on informal and formal leadership roles earlier and more frequently than their non‐Indigenous counterparts, due to social, cultural and community obligations and increased demand.4,5 Concepts of leadership can feel conflicting for Indigenous leaders who walk in two worlds — colonial notions of leadership typically value the individual and top‐down hierarchical models, whereas Indigenous concepts value collective, grassroots and consensus models.54 Young Indigenous leaders should be supported to value and find power in this tension, to successfully walk in both worlds.

Koorie Youth Council: grassroots research and advocacy to improve health

The 2018 Ngaga‐dji report, meaning “hear me” from Woiwurrung language of the Wurundjeri people, is an example of grassroots research and advocacy. Through group yarning circles and qualitative individual interviews, KYC amplified the voice for one of the most excluded and unheard populations in Australia. Ngaga‐dji collects and shares the stories of Indigenous children and young people in contact with the youth justice system, in their own voices.11 The report is a collective call to action to decision makers, the government, and the wider public to commit to reform and systemic change, and addresses root causes of Indigenous children and young people's over‐representation within the justice system.11 The three grounding principles for reform include self‐determination, youth participation, and culture, family, Elders and communities.11

One of the recommendations of the report to support children to become happy and healthy adults was to raise the age of the state supporting young people when leaving out‐of‐home‐care from 18 to 21 years.11 Victoria was the first state to enact this change due to collective advocacy from many communities and organisations including KYC.55 Many other recommendations from the Ngaga‐dji report have yet to be implemented.

Conclusion

Indigenous‐led initiatives and organisations support self‐determination, are trusted by communities, and are attuned to Indigenous concepts of health, values and worldviews.5,8,35 Youth‐led initiatives and organisations are well placed to define children and young people's needs and design creative, strength‐based solutions.36 KYC is a best‐practice example of youth‐led, Indigenous‐led participation that centres self‐determination to improve health. Given the health needs of Indigenous children and young people, there is a strong case for funding, scaling and/or replicating youth‐led, Indigenous‐led models such as KYC in other regions.

Shifting from performative non‐participation and tokenism towards meaningful participation is an essential part of creating more culturally safe services to improve the health of Indigenous children and young people. This involves redistributing power, shared decision making, and genuine partnership based on respect.4,5,8,13,56 It is the work of all decision makers, clinicians, researchers and leaders to ensure Indigenous children and young people are heard and at decision‐making tables to help create their own healthy futures.

Box 1 – Arnstein's ladder of citizen participation

Source: Arnstein S. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Plann Assoc 1969; 35: 216‐224, with permission from publisher Taylor and Francis Ltd (www.tandfonline.com).12

Box 2 – Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems model of the child

Source: Image by Ian Joslin, licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Rio_Hondo/CD_106%3A_Child_Growth_and_Development_(Andrade)/01%3A_Introduction_to_Child_Development/1.05%3A_Developmental_Theories).

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Lycett K, Cleary J, Calder R, et al. A framework for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030: tracking the health and wellbeing of children and young people to hold Australia to account. Med J Aust 2023; 219 (Suppl): S3‐S10. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/framework‐future‐healthy‐countdown‐2030‐tracking‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐children

- 2. United Nations. UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. UN, 2007. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp‐content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 3. UNICEF Australia. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [website]. https://www.unicef.org.au/united‐nations‐convention‐on‐the‐rights‐of‐the‐child (viewed May 2024).

- 4. Koorie Youth Council. Wayipunga [website]. Melbourne: Koorie Youth Council, 2024. https://koorieyouthcouncil.org.au/wayipunga/ (viewed May 2024).

- 5. SNAICC, National Voice for our Children. Family matters report 2023. Melbourne: SNAICC, 2023. https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/07/20240731‐Family‐Matters‐Report‐2023.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 6. Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap annual data compilation report, July 2023 [website]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/annual‐data‐report/2023/report (viewed May 2024).

- 7. Azzopardi PS, Sawyer SM, Carlin JB, et al. Health and wellbeing of Indigenous adolescents in Australia: a systematic synthesis of population data. Lancet 2018; 391: 766‐782.

- 8. Harfield S, Purcell T, Schioldann E, et al. Enablers and barriers to primary health care access for Indigenous adolescents: a systematic review and meta‐aggregation of studies across Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and USA. BMC Health Serv Res 2024; 24: 553.

- 9. Bower C, Watkins RE, Mutch RC, et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and youth justice: a prevalence study among young people sentenced to detention in Western Australia. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e019605.

- 10. Tarrago A, Veit‐Prince E, Brolan CE. “Simply put: systems failed”: lessons from the Coroner's inquest into the rheumatic heart disease Doomadgee cluster. Med J Aust 2024; 221: 13‐16. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2024/221/1/simply‐put‐systems‐failed‐lessons‐coroners‐inquest‐rheumatic‐heart‐disease

- 11. Koorie Youth Council. Ngaga‐dji report, August 2018. [Internet]. Melbourne: Koorie Youth Council, 2018. https://www.koorieyouthcouncil.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/09/Ngaga‐djireportAugust2018.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 12. Arnstein S. A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Plann Assoc 1969; 35: 216‐224.

- 13. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. AIATSIS engagement policy snapshot 2020. https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/research_pub/AIATSIS%20Engagement%20Policy%20Snapshot%202020.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 14. Hart RA. Children's participation: From tokenism to citizenship. Florence, Italy: United Nations Children's Fund International Child Development Centre [website]. Organiszing Engagement, 1992. https://organizingengagement.org/models/ladder‐of‐childrens‐participation/ (viewed May 2024).

- 15. White SC, Choudhury SA. The politics of child participation in international development: the dilemma of agency. Eur J Dev Res 2007; 19: 529‐550.

- 16. Gee G, Dudgeon P, Shultz C, et al. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. In: Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R; editors. Working Together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2014. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal‐health/working‐together‐second‐edition/working‐together‐aboriginal‐and‐wellbeing‐2014.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 17. Anderson K, Elder‐Robinson E, Gall A, et al. Aspects of wellbeing for Indigenous youth in CANZUS countries: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 13688.

- 18. Bamblett M, Frederico M, Harrison J, et al. “Not one size fits all”: understanding the social & emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children. Melbourne: La Trobe University, 2012. https://opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/report/_Not_one_size_fits_all_Understanding_the_social_emotional_wellbeing_of_Aboriginal_children/22239874/1 (viewed May 2024).

- 19. Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Lawrence DM, et al. The Western Australian Aboriginal Child Health Survey: the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children and young people. Perth: Curtin University of Technology and Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 2005. https://api.research‐repository.uwa.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/10057115/WAACHSVolume2.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 20. Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Dev 1974; 45: 1‐5.

- 21. Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples, 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, 2012.

- 22. Uink B, Bennett R, Bullen J, et al. Racism and Indigenous adolescent development: a scoping review. J Res Adolesc 2022; 32: 487‐500.

- 23. O'Keefe VM, Fish J, Maudrie TL, et al. Centering Indigenous knowledges and worldviews: applying the indigenist ecological systems model to youth mental health and wellness research and programs. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 6271.

- 24. Yeo SS. Bonding and attachment of Australian Aboriginal children. Child Abuse Rev 2003; 12: 292‐304.

- 25. Brown N, Azzopardi P, Stanley F. Aragung buraay: culture, identity and positive futures for Australian children. Med J Aust 2023; 219: 451‐453. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/aragung‐buraay‐culture‐identity‐and‐positive‐futures‐australian‐children

- 26. Bourke S, Wright A, Guthrie J, et al. Evidence review of Indigenous culture for health and wellbeing. Int J Health Wellness Soc 2018; 8: 11–27.

- 27. Koorie Youth Council. About us [website]. Melbourne: Koorie Youth Council, 2024. https://koorieyouthcouncil.org.au/about/ (viewed May 2024).

- 28. United Nations Women. Strategy for Inclusion and visibility of Indigenous women. New York: UN Women, 2016. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2016/Strategy‐for‐inclusion‐and‐visibility‐of‐indigenous‐women‐web‐en.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 29. Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples. UN, 2013. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/IPeoples/FreePriorandInformedConsent.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 30. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health and wellbeing of First Nations people. Burden of disease [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias‐health/indigenous‐health‐and‐wellbeing#Burden%20of%20disease (viewed May 2024).

- 31. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: summary report, March 2024. Canberra: AIHW, 2024. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/getattachment/79e5f9c5‐f5b9‐4a1f‐8df6‐187f267f6817/hpf_summary‐report‐aug‐2024.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 32. Paradies Y. Colonisation, racism and indigenous health. J Popul Res 2016; 33: 83‐96.

- 33. Koorie Youth Council. Koorie Youth Summit [website]. Melbourne: Koorie Youth Council, 2024. https://koorieyouthcouncil.org.au/koorie‐youth‐summit/ (viewed May 2024).

- 34. Stanley F, Langton M, Ward J, et al. Australian First Nations response to the pandemic: a dramatic reversal of the “gap”. J Paediatr Child Health 2021; 57: 1853‐1856.

- 35. Wilson O, Daxenberger L, Dieudonne L, et al. A rapid evidence review of young people's involvement in health research. London: Wellcome Trust, 2020. https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/2021‐02/a‐rapid‐evidence‐review‐of‐young‐peoples‐involvement‐in‐health‐research.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 36. Azzopardi P, Blow N, Purcell T, et al. Investing in the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adolescents: a foundation for achieving health equity. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 202. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/5/investing‐health‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐adolescents‐foundation

- 37. Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0138511.

- 38. Allison F, Cunneen C, Selcuk A. “In every corner of every suburb”. The Call It Out Racism Register 2022–2023. Sydney: Jumbunna Institute for Indigenous Education and Research, University of Technology Sydney; 2023. https://callitout.com.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/11/Call‐It‐Out‐Annual‐Report‐2022‐2023‐Final‐v2.pdf (viewed May 2024).

- 39. Anderson I, Paradies Y, Langton M, Calma T. Racism and the 2023 Australian constitutional referendum. Lancet 2023; 402: 1538‐1539.

- 40. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data by region [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2024. https://dbr.abs.gov.au/region.html?lyr=ste&rgn=2 (viewed May 2024).

- 41. Make It 16. Why 16? [website]. https://www.makeit16.au/why‐16 (viewed Aug 2024).

- 42. Vic treaty takes on new‐age democracy. SBS News 2019; 11 Apr. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/vic‐treaty‐takes‐on‐new‐age‐democracy/8au1fx36g (viewed May 2024).

- 43. Dillon MC. Codesign in the Indigenous Policy domain: risks and opportunities [discussion paper No. 296/2021]. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University; 2021. https://caepr.cass.anu.edu.au/research/publications/codesign‐indigenous‐policy‐domain‐risks‐and‐opportunities (viewed Oct 2024).

- 44. Anderson K, Gall A, Butler T, et al. Development of key principles and best practices for co‐design in health with First Nations Australians. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 147.

- 45. McAllister T. 50 Reasons why there are no Māori in your science department. J Glob Indig 2022; 6: 1‐10.

- 46. Bond C, Brough M, Mukandi B, et al. Looking forward looking black: making the case for a radical rethink of strategies for success in Indigenous higher education. Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 2020; 49: 153‐162.

- 47. Heifetz RA. Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 1994.

- 48. Burchill LJ, Kotevski A, Duke DL, et al. Ethics guidelines use and Indigenous governance and participation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a national survey. Med J Aust 2023; 218: 89‐93. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/2/ethics‐guidelines‐use‐and‐indigenous‐governance‐and‐participation‐aboriginal‐and

- 49. National Tertiary Education Union. NTEU celebrates the inclusion of cultural load allowance clauses into enterprise agreements for the first time ever [media release]. 10 April 2024. https://www.nteu.au/News_Articles/Media_Releases/inclusion_of_cultural_load_allowance_clauses.aspx (viewed June 2024).

- 50. Andrews S, Gallant D, Mazel O. Shifting the terrain, enriching the academy: Indigenous PhD scholars’ experiences of and impact on higher education. High Educ 2024; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734‐024‐01207‐z

- 51. Wylie L, McConkey S, Corrado AM. It's a journey not a check box: indigenous cultural safety from training to transformation. Int J Indig Health 2021; https://doi.org/10.32799/ijih.v16i1.33240

- 52. Nixon SA. The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: implications for health. BMC Public Health 2019; 19: 1637.

- 53. Sullivan‐Clarke A. Empowering relations: an Indigenous understanding of allyship in North America. Journal of World Philosophies 2020; 5: 30‐42.

- 54. Deshong M, Evans M. Australian Indigenous women and political leadership. In: Rosser‐Mims D, McNellis JR, Bailey J, Egan C; editors. Pathways into the political arena: the perspectives of global women leaders. Information Age Publishing, 2020; p 223.

- 55. Department of Families, Fairness and Housing. Home stretch [website]. Melbourne: Government of Victoria, 2024. https://services.dffh.vic.gov.au/home‐stretch (viewed May 2024).

- 56. Productivity Commission. Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap; study report, volume 1. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/closing‐the‐gap‐review/report/closing‐the‐gap‐review‐report.pdf (viewed May 2024).

We respectfully acknowledge the unceded lands on which we live, learn and work. We acknowledge the wisdom and knowledge that Elders, past, present and future, who have and will continue to ensure Indigenous ways of being, knowing and doing, are centred and passed onto children and young people for generations. Koorie Youth Council extends their appreciation to the young people who have participated and engaged with them in their work. Your insights, knowledge and experiences have been invaluable in amplifying your voices and guiding our efforts. Without your contributions, Koorie Youth Council's work would not be possible. We commit to ensuring the ideas and content in this article are also made accessible to Indigenous young people and the wider community, by participating in more readily accessible language and mediums in parallel to the publication of this article.

This article is part of the 2024 MJA supplement on the Future Healthy Countdown 2030, which was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) — a pioneer in health promotion that was established by the Parliament of Victoria as part of the Tobacco Act 1987, and an organisation that is primarily focused on promoting good health and preventing chronic disease for all.

No relevant disclosures.