In Australia, electronic cigarette (e‐cigarette) use has nearly tripled since 2019, despite legal restrictions.1 These vaping products generally contain the carrier fluids propylene glycol and glycerine, flavouring chemicals, cooling agents, and nicotine.2 Most users purchase their products outside intended sources,3,4 in what the federal government describes as a “black market”.5 At the time of the study reported in this article, a prescription was required for purchasing nicotine‐containing e‐cigarette products in Australia.6 To enable over‐the‐counter sales and prevent seizure during customs controls, some suppliers have modified the products and their packaging.2

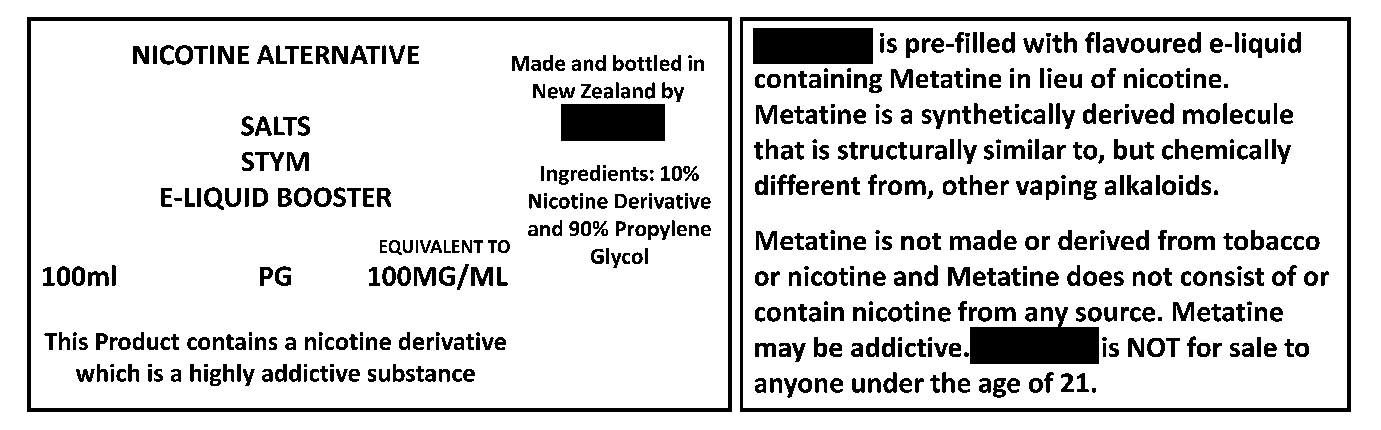

We investigated new e‐cigarette products advertised in Australia as containing a nicotine alternative (Box 1) that manufacturers claim passes routine nicotine testing (ie, no nicotine detected), facilitating their legal sale to Australian adults without prescription. We purchased e‐cigarette products from three manufacturers in November 2023: four concentrated solutions for dilution before use and five ready‐to‐use products. All samples were analysed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry methods described in our earlier publication2 (Supporting Information). The nicotine alternative was purified and fully characterised by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy and high resolution mass spectrometry. We did not seek formal ethics approval for our analysis.

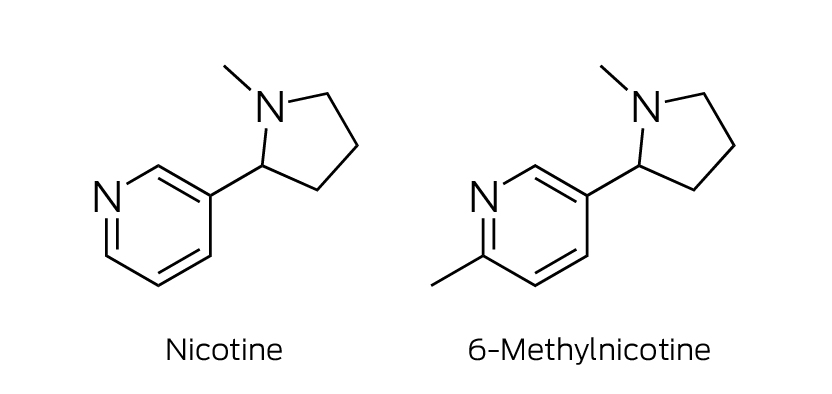

All nine products contained an ingredient that would not be identified by standard analytical testing for nicotine; complementary chemical characterisation techniques (Supporting Information) identified it as 6‐methylnicotine (Box 2, Box 3).

Only one other study has identified 6‐methylnicotine in an e‐cigarette product (one United States brand), but without complete chemical characterisation to confirm its structure.7 The in vitro affinity of 6‐methylnicotine for nicotinic cholinergic receptors is higher than that of nicotine, and its psychotropic potency three times greater.8 The cytotoxicity of 6‐methylnicotine exceeds that of nicotine at similar concentrations, and a lower dosage has been recommended for e‐cigarette products.9

The difference in toxicity between nicotine and 6‐methylnicotine is particularly concerning given the concentration of 6‐methylnicotine in the products we assessed. Samples ALT‐01 and ALT‐02, each labelled “100 mg/mL [nicotine] equivalent”, respectively contained about one‐third and one‐fifth of the equivalent listed nicotine concentration, whereas ALT‐03 and ALT‐04, labelled as “10%” solutions, contained as much as 100 mg/mL 6‐methylnicotine (Box 2). While instructions on the retailers’ websites recommended using lower concentrations of the nicotine alternative than of nicotine, this was not indicated on the product or its packaging. The differences in labelling and actual concentrations in these products could confuse users, increasing the risk of accidental exposure to high concentrations of a compound with unknown health effects. Ready‐to‐use products (ALT‐05 to ALT‐09) contained 6‐methylnicotine concentrations about an order of magnitude lower than the equivalent nicotine content of currently available nicotine‐containing e‐cigarette products2 (Box 2). Benzoic acid, included to reduce throat irritation by high nicotine concentrations by converting it to nicotine benzoate,10 was detected in seven of the nine samples. Whether conversion of 6‐methylnicotine to its benzoate salt has the same effect is unknown.

One limitation of our study was the small number of samples we analysed. We undertook a thorough internet search to identify, purchase, and analyse all products including nicotine alternatives, but compounds other than 6‐methylnicotine may also be used as nicotine alternatives.

We found that nine “nicotine alternative”‐containing e‐cigarette products sold in Australia contained 6‐methylnicotine. The concentration range determined and the limited information on the toxicity and potential health effects of 6‐methylnicotine are both concerning. The toxicology of 6‐methylnicotine and the consequences for health of inhaling it should be investigated, particularly as a long term alternative to nicotine in e‐cigarette products. Clinicians should be aware of the availability of these products in Australia, including without prescription. Recent changes to Australian regulation have banned the sale of any e‐cigarette products without prescription, closing the loophole manufacturers were using to legally distribute these products.4,5 However, further novel e‐cigarette products could be developed to circumvent the new regulations.

Box 1 – Text transcription of labels from e‐cigarette products containing a nicotine alternative: a concentrated product (ALT‐02, left) and a pod‐based (ready‐to‐use) product (ALT‐05, right)*

* Brand names redacted.

Box 2 – E‐cigarette products tested for 6‐methylnicotine concentration

|

Sample designation |

Nicotine‐related labelling |

Labelled concentration (mg/mL equivalent) |

Methylnicotine concentration (mg/mL), mean (SD)* |

Benzoic acid detected† |

Manufacturer |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Concentrated solution (for dilution) |

|||||||||||||||

|

ALT‐01 |

“nicotine derivative” |

“100 mg/mL nicotine equivalent” (100 mg/mL) |

31.4 (0.8) |

No |

1 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐02 |

“nicotine derivative” |

“100 mg/mL nicotine equivalent” (100 mg/mL) |

20 (1) |

Yes |

1 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐03 |

“nicotine alternative agent” |

10% (100 mg/mL) |

100 (10) |

No |

2 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐04 |

“nicotine alternative agent” |

10% (100 mg/mL) |

57 (4) |

Yes |

2 |

||||||||||

|

Ready‐to‐use (disposable devices or pod cartridges) |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

ALT‐05 |

“nicotine‐like experience, without the nicotine” |

5% (50 mg/mL) |

3.4 (0.4) |

Yes |

3 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐06 |

“nicotine‐like experience, without the nicotine” |

5% (50 mg/mL) |

5.4 (0.6) |

Yes |

3 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐07 |

“nicotine‐like experience, without the nicotine” |

5% (50 mg/mL) |

5.2 (0.6) |

Yes |

3 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐08 |

“no‐nicotine nicotine solution” |

None listed |

3.0 (0.2) |

Yes |

2 |

||||||||||

|

ALT‐09 |

“no‐nicotine nicotine solution” |

None listed |

2.9 (0.3) |

Yes |

2 |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

SD = standard deviation. * For three replicate measurements. † Presence of benzoic acid indicates that the nicotine alternative is present as a benzoate salt; its absence suggests that the nicotine alternative is present as the base. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 4 March 2024, accepted 13 May 2024

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey 2022–2023 (cat. no. PHE 340). 29 Feb 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/illicit‐use‐of‐drugs/national‐drug‐strategy‐household‐survey (viewed Mar 2024).

- 2. Jenkins C, Powrie F, Morgan J, Kelso C. Labelling and composition of contraband electronic cigarettes: analysis of products from Australia. Int J Drug Policy 2024; 128: 104466.

- 3. Pettigrew S, Miller M, Alvin Santos J, et al. E‐cigarette attitudes and use in a sample of Australians aged 15–30 years. Aust N Z J Public Health 2023; 47: 100035.

- 4. Therapeutic Goods Administration (Department of Health and Aged Care). Changes to the regulation of vapes. Updated 25 July 2024. https://www.tga.gov.au/products/unapproved‐therapeutic‐goods/vaping‐hub/reforms‐regulation‐vapes (viewed July 2024).

- 5. Minister for Health and Aged Care. Taking action on smoking and vaping [press release]. 2 May 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the‐hon‐mark‐butler‐mp/media/taking‐action‐on‐smoking‐and‐vaping (viewed July 2024).

- 6. Morgan J, Breitbarth AK, Jones AL. Risk versus regulation: an update on the state of e‐cigarette control in Australia. Intern Med J 2019; 49: 110‐113.

- 7. Jordt SE, Jabba SV, Zettler PJ, Berman ML. Spree Bar, a vaping system delivering a synthetic nicotine analogue, marketed in the USA as “PMTA exempt”. Tob Control 2024: tc‐2023‐058469 [online ahead of print].

- 8. Wang DX, Booth H, Lerner‐Marmarosh N, et al. Structure–activity relationships for nicotine analogs comparing competition for [3H]nicotine binding and psychotropic potency. Drug Dev Res 1998; 45: 10‐16.

- 9. Qi H, Chang X, Wang K, et al. Comparative analyses of transcriptome sequencing and carcinogenic exposure toxicity of nicotine and 6‐methyl nicotine in human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicol in Vitro 2023; 93: 105661.

- 10. Leventhal AM, Madden DR, Peraza N, et al. Effect of exposure to e‐cigarettes with salt vs free‐base nicotine on the appeal and sensory experience of vaping: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4: e2032757.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by University of Wollongong, as part of the Wiley – University of Wollongong agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data sharing:

The data underlying this study are available on request by contacting the corresponding author.

This project was funded (purchase and analysis of samples) by the University of Wollongong, Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health Small Grant Scheme.

No relevant disclosures.