The known: Australian health and medical research organisations have lagged behind international initiatives to improve the integration of sex and gender in research, potentially resulting in low quality research and inequitable health outcomes.

The new: Most Australian health and medical research organisations have policies regarding the reporting of sex and gender in research. However, many of these organisations refer to local policies or overseas guidelines rather than dedicated organisation‐specific policies.

The implications: Research policy and guidelines for integrating sex and gender into health and medical research must be implemented and evaluated across Australian health and medical research to achieve change.

Inadequate consideration of sex and gender in health and medical research has an impact on everyone: women, men, and those who do not identify with a specific gender, including non‐binary and agender people. Sex and gender influence a person's risk of disease, access to treatment, and response to management.1 Improved data collection and analysis, and the reporting of sex‐ and gender‐disaggregated data can promote more rigorous, reproducible, and responsible science, leading to recognition of sex‐ and gender‐related phenomena, fewer erroneous conclusions and less low value research, better targeted treatments, and ultimately better health outcomes.2,3,4 Increased integration of sex‐ and gender‐related concepts and practices also supports a human rights‐based approach to research by promoting participation, non‐discrimination, and access to the benefits of scientific research and better health for all.

Policies that emphasise the integration of sex and gender in health and medical research can facilitate this aim. Important progress and success in advancing standards of sex and gender analysis have been achieved.5,6,7,8 Since 2020, the European Commission has required that grant recipients integrate sex and gender analysis into their study design.5 More recently, a subset of Nature portfolio journals have required researchers to state how sex and gender were considered in their work, or to justify why they were not.8 In 2020, we reported that most funding agencies and peer‐reviewed journals in Australia did not have policies on integrating sex and gender into medical research.9 Our report included a call to action by all concerned, not just funders and journals, to raise awareness of the question and to support sex and gender analysis in health and medical research.

Building on our earlier report, we investigated a broader spectrum of Australian health and medical research organisations, including research creators and educators, evidence synthesisers, and research advocacy groups, peak bodies, and societies. Our aim was to identify key organisations in Australian health and medical research, to explore their policies on defining, collecting, analysing, and reporting data on sex and gender, and to identify barriers to and facilitators of developing and implementing such policies.

Methods

In humans, sex is largely a legal status, with categories of male or female in most jurisdictions, typically based on the presumption or observation at birth by a medical professional of external sex characteristics. A person's sex can be changed over the course of their lifetime and may therefore differ from sex recorded at birth.10,11 Some people have innate variations of sex characteristics that do not fit medical norms for female and male bodies (intersex).12 Gender is usually defined as a socio‐cultural construct that refers to the way in which a person identifies or expresses themselves, including behaviour, attitudes, appearance, and habits. A person's gender identity or gender expression is not always binary, and may change over time. Gender is often considered to be distinct from sex, but it is recognised that the scientific and legal categorisation of sex relies on socio‐cultural constructs regarding sex differences between male and female bodies.13 Gender‐related attitudes and behaviours are complex and change with time and place,14 and variations in other social categories, such as age, ethnic background, class, and disability, typically intersect with gender differences. Gender also encompasses gender norms and gender relations, including power relationships and different cultural expectations regarding masculinity and femininity.4

Sex and gender policies are defined as policies, procedures, statements, or guidelines for defining, collecting, analysing, or reporting data on sex and gender in health and medical research.10

Peak bodies is a term used in Australia and New Zealand to denote “representative bodies that provide advocacy, representation, coordination, information, research and policy development on behalf of member organisations within a given sector or representing a specific section of the population.”15

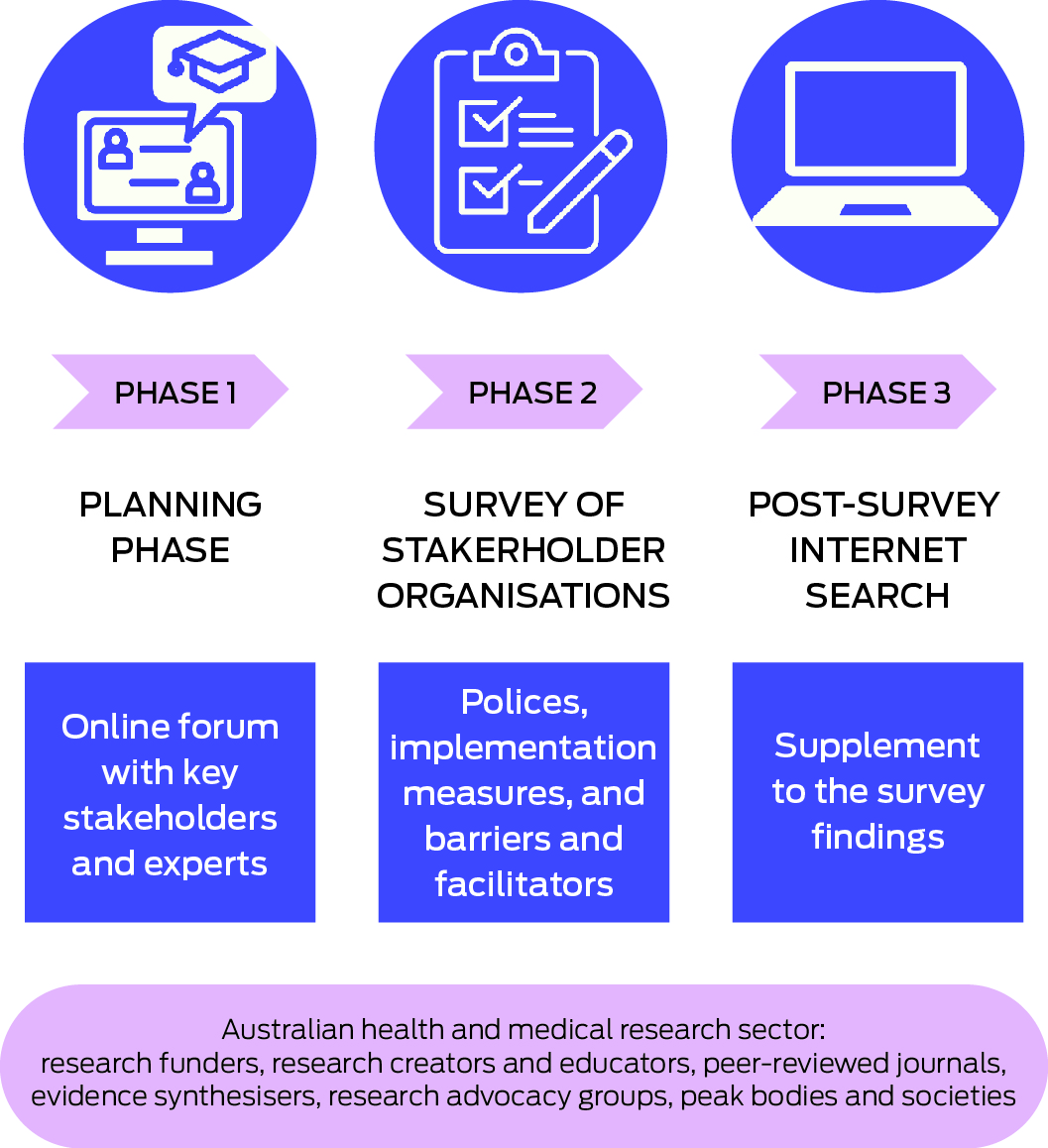

Our mixed methods study was conducted in three phases: a planning phase (expert consultation); a survey of key organisations connected with health and medical research in Australia; and a post‐survey internet search (Box 1).

Planning phase: online planning forum

To inform the survey phase of our study, an online planning forum was held on 19 May 2021. Participants were recruited using snowball methods; we initially invited participants in our earlier study,9 and then invited researchers, clinicians, policy makers, and representatives of advocacy groups and community organisations suggested by the participants at an earlier forum.16 The aims of the 2021 forum were to ascertain local barriers to and facilitators of the development and implementation of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research in Australia; to validate our approach to identifying key organisations in Australian health and medical research; and to provide recommendations about the organisations in five areas of health and medical research in Australia — research creators and educators, evidence synthesisers, and research advocacy groups, peak bodies and societies, as well as the research funders and peer‐reviewed journals included in our earlier study9 (Box 2) — who should be invited to participate in our survey. A program provided to forum participants outlined its aims and anticipated outcomes, including lists of barriers and facilitators to implementing policies. During the forum, participants were randomly allocated to online breakout groups; group leaders used nominal group techniques to assist discussions about barriers and facilitators and the identification of additional relevant organisations.

Survey of organisations involved in health and medical research in Australia

A cross‐sectional survey was developed in accordance with the aims of the study and pre‐tested with a range of academic researchers at the George Institute for Global Health and the Australian Human Rights Institute, University of New South Wales (Supporting Information, table 1). The survey was then sent to a convenience sample of organisations identified during the planning phase. People in leadership positions or staff members responsible for organisation policy development (based on publicly available information) were invited by email to participate in the online survey, available during 1 August – 23 November 2021; they were contacted by phone if they did not respond to the email. Participants had access to the survey after providing personal informed consent to participation. The 22‐question survey covered three main areas: policies, procedures, statements, or guidelines regarding the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in research at the participant's organisation; implementation and evaluation measures for these policies; and pre‐specified barriers to and facilitators of developing and implementing such policies in their organisation. Password‐protected, anonymised survey data were stored on secure computer servers at the George Institute for Global Health; only study personnel, bound by strict confidentiality agreements, had access to the data.

Post‐survey internet search for policies

Supplementary internet searches for publicly accessible policies, procedures, statements, or guidelines regarding the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex‐ and gender‐specific health data on the websites of all organisations invited to participate in the survey was undertaken during 24 January – 11 February 2022 and 23 November – 12 December 2022. The searches conformed with the methods for our earlier article:9 on each organisation website we searched for “sex, gender, demographics, representation/representative/underrepresented, diversity/diverse, inclusion/inclusive, woman/women, man/men, female, male”. Relevant webpages or documents were classified into three categories: dedicated policy: dedicated organisation‐specific sex and gender policies (the entire document met the definition of a sex and gender policy as defined above); content in another research policy (policies, guidelines, or statements with broader aims, but including content that met the definition of a sex and gender policy as defined above); and references to external policies (references to policies, guidelines, or statements from external sources that met the definition of a sex and gender policy, either in their entirety or because of specific content).

Ethics approval

The survey was approved by the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney) Human Research Ethics Committee (HC210326).

Results

Online planning forum

Fifty‐one of 61 invited people connected with health and medical research participated in the online expert forum; ten were early to mid‐career researchers, ten were people with lived experience or community members, and 31 were senior researchers, academics, or professional staff members. They identified several barriers to and facilitators of policy development and implementation in the areas of leadership, language and definitions, financial costs, integration with established systems (including infrastructure, resources, processes), knowledge skills and training, and community acceptance. These barriers and facilitators were subsequently reflected in the survey questions.

The forum participants identified 138 organisations connected with health and medical research in Australia; after removing duplicates and assessment of their relevance, 65 were included in our final list, including fifteen research creators and educators, ten evidence synthesisers, and twenty research advocacy, peak bodies, and societies, as well as the ten research funders and ten peer‐reviewed journals included in our earlier report9 (Supporting Information, table 2).

Survey of organisations involved in health and medical research in Australia

Twenty of 65 organisations responded to our survey invitations. Seven organisations reported at least one relevant policy, and six had plans to develop or implement such policies during the following two years (Box 3).

In terms of implementation and evaluation measures, eight organisations referred to external resources regarding training and capacity building (Supporting Information, table 3). In most cases, each resource was mentioned by only one organisation; the Australian Bureau of Statistics Standard for sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation17 was mentioned by three organisations. No organisations reported policy evaluation measures.

Seventeen of the twenty organisations responded to questions about barriers to developing and implementing policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research (mean, two barriers; range, zero to five). The most frequently reported were lack of tools and training, language definitions, lack of content expertise, and lack of local examples of successful policies. Four organisations reported no barriers. Five of the barriers identified during the planning phase were not reported by any organisation, and three organisations reported other barriers, including policy development not being the responsibility of the organisation and inadequate staff member numbers or capacity (Box 4).

The same seventeen organisations responded to questions about facilitators of the development and implementation of policies on the collection, analysis and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research (mean, five facilitators; range, one to eleven). The key facilitators were greater awareness of the rationale for sex and gender incorporation, support for cultural shift in research practice, intersectional approach, and development of tools and standards. Three organisations reported other facilitators, including more local and global collaborations, and advice specifically for sex‐ and gender‐sensitive survey design (Box 5).

Post‐survey internet search for policies

Fifty‐seven of the 65 organisations had some form of sex and gender policy, including all ten journals and five of ten funders (Box 6). Twelve organisations, including eight peak bodies, have published dedicated sex and gender policies on their websites. Fourteen organisations referred to documents that included content about sex and gender in research in another research policy, including checklists and guidelines for different types of evidence synthesis, and guidelines for conducting trials or preparing regulatory applications.

Thirty‐eight organisations referred to external policies, often referring to the same documents (Box 6). These references were largely to national and international ethics guidelines, medical publishing guidelines, and study design‐specific guidelines and checklists. Five organisations referred to specific external policies on sex and gender in research, including the Australian Bureau of Statistics standard,17 the Sex and gender equity in research (SAGER) guidelines,18 the National Institutes of Health Sex as a biological variable policy,19,20 and a Health Canada guideline.21

Discussion

We found that a diverse group of organisations is actively involved in the integration of sex and gender in health and medical research in Australia. While the response rate for our survey was lower than expected (30%), we identified a number of organisations leading this area, and others with plans to develop organisation‐specific policies. Our survey was supplemented by an internet search which found that most organisations invited to participate in the survey had dedicated policies or relevant content in other research policies, or referred to external policies on sex and gender in health and medical research. Our findings build on our earlier report,9 providing a more comprehensive picture of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in Australian health and medical research.

Specific sex and gender policies improve the integration of sex and gender in health and medical research. For example, in response to the Canadian government sex‐and‐gender‐based analysis (SGBA) policy, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research introduced SGBA requirements and interventions for all applicants for funding by the national health research funding program and for grant application evaluators. Interventions included training opportunities, resources, and explicit instructions to applicants and evaluators. A ten‐year longitudinal evaluation found that the number of grant applications including consideration of sex and gender had subsequently increased, and that such consideration was associated with application success.22 The authors of the study emphasised the importance of the SGBA policy being implemented by a national agency.

There was little consistency in the sex and gender policies and resources used in the Australian health and medical research community, suggesting a lack of inter‐organisational collaboration. A study of sex and gender research policies in the United States, Canada, and the European Union found that their successful integration requires the coordination of multiple organisations, and that one organisation or agency in each country or union led the way in incorporating sex and gender into the research process.3 In order to educate the scientific community about how to appropriately take sex and gender into account in research, each lead organisation needs to collaborate with and support the development of a lead policy agency that monitors, evaluates, and supports engagement with concepts and practices related to sex and gender across all aspects of research.

The integration of sex and gender into health and medical research has increased, as illustrated by the Medical Journal of Australia recommendation that authors follow the SAGER guidelines23 and the National Health and Medical Research Council Gender equity strategy 2022–2025, which noted that the development of a statement on sex and gender inclusivity in research design is a priority.24 However, there are still barriers to implementation, mostly related to inadequate awareness, understanding, leadership, and guidance in adapting systems to incorporate sex and gender data. Most of these problems can be overcome by robustly developed and disseminated training resources and tools. In a review of government‐based research funding agencies that developed policies on the integration of sex and gender into medical research, positive outcomes were associated with investment in implementing policies and requirements, providing incentives and resources, developing training resources, and holding appropriately targeted workshops.3

In the past five years, progress has been made in the development and implementation of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in Australian health and medical research. In our 2017 internet search for policies related to sex and gender, we found that only six of the ten leading peer‐reviewed journals and two of the ten leading funding agencies in Australia had such policies;9 five years later, all ten leading journals and five of ten funders had some form of relevant policy. In 2024, the National Health and Medical Research Council and the Department of Health and Aged Care, jointly responsible for the Medical Research Future Fund, released a statement on Sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation in health and medical research for public consultation, which included as an aim “improving consideration of… sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation throughout the design, conduct, analysis, reporting, translation and implementation of all research”.25 Moreover, the Association of Australian Medical Research Institutes released their Sex and gender policy recommendations for health and medical research in 2023, advocating “the need to raise awareness and encourage considerations of sex, sex characteristics, sex and gender variables in health and medical research, where appropriate.”26 Having these policies is a necessary first step, but will it be sufficient to increase the integration of sex and gender in health and medical research? An analysis of original research articles published by the ten leading Australian medical journals in 2020 found no association between endorsement of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines, which provide criteria for reporting sex and gender, and adherence to these guidelines.27 External monitoring and evaluation of compliance to a policy (including, for example, our reports) effectively highlight the problem, but they are not sufficient for achieving the required organisational commitment. Policy implementation requires support for researchers, reinforced by regular internal monitoring of compliance and evaluations of barriers and facilitators to compliance at the organisational level.

Limitations

We performed a systematic examination of sex and gender policies in health and medical research, as well as of the barriers to and facilitators of their development and implementation. However, as the response rate for our survey was low, we conducted a post‐survey internet search for publicly available policies of all invited organisations. The representativeness of the 65 health and medical research organisations included is unclear. Some relevant organisations may not have been identified during the planning phase, and the individuals who completed the survey may not have had full knowledge of organisation policies. We did not review the content of sex and gender policies submitted by the organisations for the survey. Further analysis of organisational policies using a comprehensive checklist, such as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Integrating sex and gender checklist,28 is needed to better assess the sex and gender policy landscape in Australia. In addition, we did not use a robust implementation framework, which may limit change processes. Future studies should more comprehensively examine policies in qualitative interviews and use implementation frameworks (eg, Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment29) to collaborate with experts in implementation science to gather stronger evidence for policy change. It is also crucial to evaluate whether policies are implemented.

Conclusion

We are at a critical point in the long history of building awareness of the significance of sex and gender in health and medical research, both in Australia and around the world. While many research‐related organisations now have policies for guiding this change, inter‐organisational collaboration is needed to overcome barriers to and promote facilitators of implementing these policies, and to ensure that our understanding of both the importance and the complexity of these matters continues to grow.

Box 1 – The three phases of our mixed methods study of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research in Australia

Box 2 – Types of organisation involved in health and medical research in Australia included in our study of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research

|

Organisation type |

Selection strategy |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Research funders |

Ten leading research funding agencies in Australia, identified by the University of New South Wales research office.9 |

||||||||||||||

|

Peer‐reviewed journals |

Ten leading peer‐reviewed Australian medical journals, identified using InCites in Web of Science (Clarivate).9 |

||||||||||||||

|

Researcher creators and educators |

All Group of 8 universities in Australia were included (https://go8.edu.au); we initially contacted people in the medical or health faculties. High profile independent medical research institutes were also selected, based on the SCImago institute ranking (https://www.scimagojr.com). Three industry research organisations were selected by convenience sampling. |

||||||||||||||

|

Evidence synthesisers |

Purposively sampled organisations defined as responsible for synthesising medical research evidence and producing clinical or policy recommendations. |

||||||||||||||

|

Research advocacy groups, peak bodies, and societies |

Purposively sampled organisations representing basic science, public health and health promotion, clinical research, and consumer organisations. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Organisations that responded to our survey of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research in Australia

|

|

Survey participation |

Relevant policies |

|||||||||||||

|

Organisations |

Invited |

Responded |

Current |

Plans to develop |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Research funders |

10 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||||

|

Peer‐reviewed journals |

10 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

|||||||||||

|

Research creators and educators |

15 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||||

|

Evidence synthesisers |

10 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|||||||||||

|

Research advocates, peak bodies, societies |

20 |

9 |

3 |

4 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Barriers to the development or implementation of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research in Australia: survey responses by 17 organisations

|

Barrier identified during the planning phase |

Survey participants |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Informatics or other system adaptations are required to implement these policies |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Linguistic and definitional challenges associated with sex and gender |

4 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of content expertise in definitions, mechanisms, design, analysis and reporting of sex and gender |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of local examples of successful policies |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

Complexity of the field and related fear of doing the wrong thing |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Increased cost for conducting disaggregated analysis, as larger studies are needed |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Work is limited by the research evidence that is collected by others, so perceived as not relevant to our organisation |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Policies are not relevant to research content area, or not convinced this is an issue for research |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Conflicting frameworks across disciplines |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of expertise in policy development |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of leadership and institutional buy‐in |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

These policies are thought to be too prescriptive |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

External guidelines already exist (such as ICMJE guidelines), so additional guidelines are not required |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

Gender bias |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

Lack of up‐to‐date evidence of why this is important |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

Limitations of current research methods (recruitment, small sample sizes, extrapolating effectiveness from efficacy) |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

Policies promote an approach that is not hypothesis‐driven |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

Other barriers |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

No barriers |

4 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ICMJE = International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (https://www.icmje.org). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Facilitators of the development or implementation of policies on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research in Australia: survey responses by 17 organisations

|

Facilitator identified during the planning phase |

Survey participants |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Greater awareness or understanding of the rationale for sex and gender incorporation |

13 |

||||||||||||||

|

Supporting cultural shift in research practice |

11 |

||||||||||||||

|

Integrating the analysis of sex and gender with other issues, such as ethnicity |

10 |

||||||||||||||

|

Development and use of standards and consistent tools |

10 |

||||||||||||||

|

Training and support in definitions, mechanisms, design, analysis and reporting of sex and gender |

9 |

||||||||||||||

|

Significant Australian organisations leading by example |

9 |

||||||||||||||

|

Local individual champions |

7 |

||||||||||||||

|

Significant international organisations leading by example |

6 |

||||||||||||||

|

Training and support in policy development and evaluation |

5 |

||||||||||||||

|

Regulation or enforcement of policy requirements |

5 |

||||||||||||||

|

Awards, recognition, or other incentives |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Provision of additional funding to increase study sample sizes |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Supporting infrastructure changes |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Other facilitators |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

None |

0 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Organisations with at least one type of policy on the collection, analysis, and reporting of sex and gender in health and medical research

|

Characteristic |

Funders |

Peer‐reviewed journals |

Research creators and educators |

Evidence synthesisers |

Research advocates, peak bodies and societies |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of organisations |

10 |

10 |

15 |

10 |

20 |

||||||||||

|

Dedicated policy |

1 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

8 |

||||||||||

|

Content in another research policy |

2 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

||||||||||

|

Reference to external policy |

5 |

10 |

11 |

5 |

7 |

||||||||||

|

Any type of policy |

5 |

10 |

13 |

7 |

12 |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Received 14 February 2023, accepted 29 April 2024

- Cheryl Carcel1

- Amy Vassallo1,2

- Laura Hallam1

- Janani Shanthosh1,2

- Kelly Thompson1,3

- Lily Halliday2

- Jacek Anderst1

- Anthony KJ Smith4

- Briar L McKenzie1

- Christy E Newman4

- Keziah Bennett‐Brook1

- Zoe Wainer5,6

- Mark Woodward1,7

- Robyn Norton1

- Louise Chappell2

- 1 The George Institute for Global Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Australian Human Rights Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District (NSW Health), Penrith, NSW

- 4 Centre for Social Research in Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

- 5 The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 6 Victorian Department of Health, Melbourne, VIC

- 7 The George Institute for Global Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom

Correspondence: c.carcel@unsw.edu.au

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley – University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data sharing:

To request access to de‐identified data, please contact the corresponding author.

We acknowledge the contributions of Jacqui Webster, Colman Taylor, and Elizabeth Duck‐Chong to this study as part of our Advisory Group (https://www.sexandgenderhealthpolicy.org.au/our‐team). Cheryl Carcel is supported by a Heart Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (102741) and a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator grant (Emerging Leadership 1; APP2009726), Kelly Thompson by an NHMRC Investigator grant (Emerging Leadership 1, APP1194058), and Mark Woodward by an NHMRC Investigator grant (APP1174120), and program grant (APP1149987). An anonymous philanthropic donor provided monetary support for the study but had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or write‐up of the study.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Rexrode KM, Madsen TE, Yu AYX, et al. The impact of sex and gender on stroke. Circ Res 2022; 130: 512‐528.

- 2. Woodward M. Rationale and tutorial for analysing and reporting sex differences in cardiovascular associations. Heart 2019; 105: 1701‐1708.

- 3. White J, Tannenbaum C, Klinge I, et al. The integration of sex and gender considerations into biomedical research: lessons from international funding agencies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106: 3034‐3048.

- 4. Tannenbaum C, Ellis RP, Eyssel F, et al. Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering. Nature 2019; 575: 137‐146.

- 5. European Commission. Gender equality in Horizon 2020 [fact sheet]. 9 Dec 2013. https://genderedinnovations.stanford.edu/FactSheet_Gender_091213_final_2.pdf (viewed Mar 2024).

- 6. National Institutes of Health. NIH policy guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research. Updated 6 Dec 2017. https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women‐and‐minorities/guidelines.htm (viewed Aug 2024).

- 7. Peters SAE, Babor TF, Norton RN, et al. Fifth anniversary of the Sex And Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines: taking stock and looking ahead. BMJ Glob Health 2021; 6: e007853.

- 8. Nature journals raise the bar on sex and gender reporting in research [editorial]. Nature 2022; 605: 396.

- 9. Wainer Z, Carcel C. Sex and gender in health research: updating policy to reflect evidence. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 57‐62. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/2/sex‐and‐gender‐health‐research‐updating‐policy‐reflect‐evidence

- 10. Sex and Gender in Health and Medical Research Australia Group. Project glossary (terms and definitions for “sex and gender policies in health and medical research”). 2021. https://www.sexandgenderhealthpolicy.org.au/glossary (viewed July 2024).

- 11. Johnson JL, Greaves L, Repta R. Better science with sex and gender: facilitating the use of a sex and gender‐based analysis in health research. Int J Equity Health 2009; 8: 14.

- 12. Monro S, Carpenter M, Crocetti D, et al. Intersex: cultural and social perspectives. Cult Health Sex 2021; 23: 431‐440.

- 13. Fausto‐Sterling A. Gender/sex, sexual orientation, and identity are in the body: how did they get there? J Sex Res 2019; 56: 529‐555.

- 14. Brady B, Rosenberg S, Newman CE, et al. Gender is dynamic for all people. Discov Psychol 2022; 2: 41.

- 15. Sawer, M. Governing for the mainstream: implications for community representation. Australian Journal of Public Administration 2022: 61: 39‐49.

- 16. George Institute for Global Health. Ensuring the collection, analysis and reporting of sex‐ and gender‐specific health data in Australia. 29 May 2018. https://www.georgeinstitute.org/events/ensuring‐the‐collection‐analysis‐and‐reporting‐of‐sex‐and‐gender‐specific‐health‐data‐in (viewed Feb 2024).

- 17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standard for sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation variables, 2020. 14 Jan 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/standards/standard‐sex‐gender‐variations‐sex‐characteristics‐and‐sexual‐orientation‐variables/2020 (viewed June 2021).

- 18. Heidari S, Babor TF, De Castro P, et al. Sex and Gender Equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Res Integr Peer Rev 2016; 1: 2.

- 19. Office of Research on Women's Health (National Institutes of Health). NIH policy on sex as a biological variable. Undated. https://orwh.od.nih.gov/sex‐gender/orwh‐mission‐area‐sex‐gender‐in‐research/nih‐policy‐on‐sex‐as‐biological‐variable (viewed Mar 2024).

- 20. National Institutes of Health. Consideration of sex as a biological variable in NIH‐funded research. 9 June 2015. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice‐files/not‐od‐15‐102.html (viewed May 2022).

- 21. Health Canada. Considerations for inclusion of women in clinical trials and analysis of sex differences. 29 May 2013. https://www.canada.ca/en/health‐canada/services/drugs‐health‐products/drug‐products/applications‐submissions/guidance‐documents/clinical‐trials/considerations‐inclusion‐women‐clinical‐trials‐analysis‐data‐sex‐differences.html (viewed Apr 2022).

- 22. Haverfield J, Tannenbaum C. A 10‐year longitudinal evaluation of science policy interventions to promote sex and gender in health research. Health Res Policy Syst 2021; 19: 94.

- 23. Dorrigan A, Zuccala E, Talley NJ. Striving for gender equity at the Medical Journal of Australia. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 138‐139. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/217/3/striving‐gender‐equity‐medical‐journal‐australia

- 24. National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC gender equity strategy 2022–2025. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/research‐policy/gender‐equity/nhmrc‐gender‐equity‐strategy‐2022‐2025. (viewed Jan 2022).

- 25. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care; National Health and Medical Research Council. Statement on sex, gender, variations of sex characteristics and sexual orientation in health and medical research. Aug 2024. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/research‐policy/gender‐equity/statement‐sex‐and‐gender‐health‐and‐medical‐research (viewed Aug 2024).

- 26. Association of Australian Medical Research Institutes. What should AAMRI do to support improved use of sex and gender in research practices and decision making: a deliberative panel approach. Response to the recommendations. 14 Sept 2023. https://aamri.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/09/AAMRIs‐Sex‐and‐Gender‐Policy‐Recommendations‐for‐Health‐and‐Medical‐Research.pdf (viewed Mar 2024).

- 27. Hallam L, Vassallo A, Hallam C, et al. Sex and gender reporting in Australian health and medical research publications. Aust N Z J Public Health 2023; 47: 100005.

- 28. Canadian Institute for Health Research. Integrating sex & gender checklist: partnership development grants for the healthy & productive work initiative. Updated 18 Nov 2015. https://www.cihr‐irsc.gc.ca/e/49336.html (viewed Aug 2024).

- 29. Moullin JC, Dickson KS, Stadnick NA, et al. Ten recommendations for using implementation frameworks in research and practice. Implement Sci Commun 2020; 1: 42.

Abstract

Objective: To explore the policies of key organisations in Australian health and medical research on defining, collecting, analysing, and reporting data on sex and gender, and to identify barriers to and facilitators of developing and implementing such policies.

Study design: Mixed methods study: online planning forum; survey of organisations in Australian health and medical research, and internet search for policies defining, collecting, analysing, and reporting data by sex and gender in health and medical research.

Setting, participants: Australia, 19 May 2021 (planning forum) to 12 December 2022 (final internet search).

Main outcome measures: Relevant webpages and documents classified as dedicated organisation‐specific sex and gender policies; policies, guidelines, or statements with broader aims, but including content that met the definition of a sex and gender policy; and references to external policies.

Results: The online planning forum identified 65 relevant organisations in Australian health and medical research; twenty participated in the policy survey. Seven organisations reported at least one relevant policy, and six had plans to develop or implement such policies during the following two years. Barriers to and facilitators of policy development and implementation were identified in the areas of leadership, language and definitions, and knowledge skills and training. The internet search found that 57 of the 65 organisations had some form of sex and gender policy, including all ten peer‐reviewed journals and five of ten research funders; twelve organisations, including eight peak body organisations, had published dedicated sex and gender policies on their websites.

Conclusion: Most of the organisations included in our study had policies regarding the integration of sex and gender in health and medical research. The implementation and evaluation of these policies is necessary to ensure that consideration of sex and gender is adequate during all stages of the research process.