The known: Clinical registries are data repositories that monitor clinical quality indicators which are used for quality improvement of clinical standards and health care effectiveness in Australia. It is not clear if quality improvement processes from registries include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

The new: Between 17 January 2022 and 30 April 2023, 107 registries were registered with the Australian Register of Clinical Registries, and 39% of these clinical registries did not record any ethnicity data for patients. The vast majority of registries (93%) did not have Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation on registry governance or steering committees or approval from an Aboriginal human research ethics committee.

The implications: Variability exists in application of Indigenous governance of data by clinical quality, affecting the visibility of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals’ needs for policy, clinical models of care, health services and initiatives. Radical change is required, and clinical registries must work with peak bodies and stakeholders to ensure that quality improvement initiatives target populations in greatest need of this change.

Clinical registries are epidemiological repositories that provide systematic clinical quality indicator monitoring for clinical domains.1,2,3 Most clinical registries have nationally accepted quality indicators drawn from clinical models of care, providing feedback on adherence and performance.1,2 Such monitoring enacted through clinical registries is essential for continued quality improvement in clinical standards and effectiveness in health care, through identifying and addressing gaps in clinical quality outcomes.2 Ongoing monitoring of clinical quality indicators with adaptation for continued improvement can play an important role in improving health outcomes for priority populations.2,4

In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are disproportionately affected with a greater burden of disease and injury compared with the non‐Indigenous Australian population. These inequities include a risk of hospitalisation that is 2–10 times greater for injury or chronic conditions, higher diagnosis and mortality rates for preventable cancers, and a life expectancy that is 10 years lower than that for other Australians, along with significant barriers to accessing affordable and equitable health care.5,6,7 These high rates of disease and poor health and social outcomes reflect the ongoing marginalisation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, and systematic racism embedded in the health system — a continued legacy from colonisation.6

The National Strategy for Clinical Quality Registries and Virtual Registries (2020–2030) and the Framework for Australian clinical quality registries by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (the Commission) have key priority action areas aimed at addressing health inequities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.2,8 One way in which they are implemented is through principles of Indigenous Governance of Data (IG‐Data), which are formal structures for management and governance of any data (procedures, policies, reporting, translation) which relate to or affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.9

Currently it is not known how, or if, Australian clinical quality registries contain clinical quality indicators on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity, if registries have Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation on governance or steering committees, or if registries have Aboriginal human research ethics committee (AHREC) approval. In this audit, we sought to understand these unknowns, focusing on how Australian clinical quality registries engage with IG‐Data, through registry items for recording ethnicity, ethics approvals, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representation on registry governance or steering committees.

Methods

Design and participants

The Australian Register of Clinical Registries (ARCR) was established by the Commission, and contains summary information and activity on clinical registries, that have voluntarily registered, to enhance understanding, awareness and collaboration across the health care sector.10 The ARCR contains standard information on registries: identification, condition, clinical domain, registry name, abbreviation, contact information, data custodians, reporting mode and ethics. It does not contain clinical quality indicators or items recorded and reported by discrete registries.

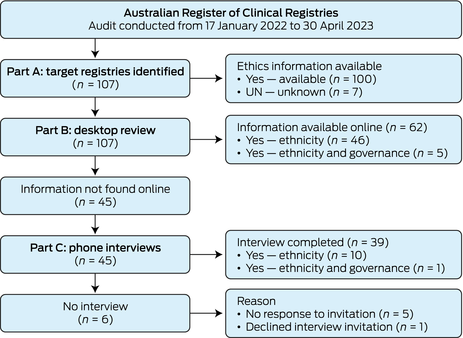

This audit involved a review of all registries in the ARCR from 17 January 2022 to 30 April 2023. General registry demographics were collected from the ARCR: registry establishment year, clinical domain, geographical coverage (international, national, etc), and ethics approval body. Examination of IG‐Data was undertaken by identifying if and how registries collected participant ethnicity, if ethics approval was provided and by whom, and if there was Indigenous representation on registry governance or steering committees. Ethnicity, rather than Indigenous status, as an item was investigated, because Indigenous status is commonly embedded in ethnicity as a data item in registries. The registry audit was conducted over three parts (Box 1): target registries were identified in Part A, identified registries were examined by desktop review in Part B, and registries moved to Part C of the audit (phone interviews) if ethnicity item reporting was not found during the desktop review.

Study governance, ethics approval and analysis

Our investigative team was led by an Aboriginal researcher (CR). Indigenous knowledges (knowing, being and doing) were important for the overall focus and conceptualisation of outcomes. The lead researcher engaged their lived experience in Indigenous Data Governance and registry work, in the context of outcomes, and used yarning with the investigative team to determine the main themes for reporting. Ethics approval was acquired from the Human Research Ethics Committee at UNSW Sydney (HC210907). Ethics approval was not sought from an AHREC as no data were collected from Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples. Data were collected in Microsoft Excel and imported into Stata 14 for calculation of descriptive statistics (frequencies and proportions).

Results

Registry audit

The audit was conducted from 17 January 2022 to 30 April 2023 (Box 2). In Part A, a total of 107 registries were identified in the ARCR (Supporting Information, Table 1). Part B, the desktop review, provided item information on 62 registries (58%). A total of 45 registries (42%) were marked as unknown for their ethnicity collection and invited to a phone interview in Part C, in which 39 registries participated (87% response rate). One registry declined to participate due to time constraints and five registries did not respond to email requests.

Registry demographics

Of the 107 registries, 40 (37%) were binational (including both Australia and New Zealand), followed by state (26 [24%]) and national (25 [23%]) registries, with smaller numbers of regional (10 [9%]) and international (5 [5%]) registries (Box 3). The majority of registries were young, with 58 registries (54%) having been established for 10 years or less. Only 69 registries (64%) included a prioritised clinical domain area in the ARCR. In terms of broad clinical domain, 29 registries (27%) focused on high burden cancers or cancers, and 11 registries (10%) focused on each of the following: musculoskeletal disorders; critical care; and cardiac, stroke and ischaemic heart disease. Other broad clinical domain areas for registries included: trauma, burns and injury; diabetes; dementia; and maternity.

Ethnicity collection

In total, 65 registries (61%) collected ethnicity data (Box 4). Of these registries, 24 (37%) were binational, 19 (29%) were national and 19 (29%) were state based (Box 5). Indigenous status was embedded in the ethnicity data item (Box 4); of the registries that collected ethnicity data, 62 (95%) collected Indigenous status data, and another five (8%) collected data on other ethnicities. Of the 62 registries collecting Indigenous status, 29 (47%) registries classified this item as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (Box 4). None of these 29 registries collected ethnicity data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals at a regional level (eg, Koori, Nunga) or at a language group or community level (eg, Kaurna, Larrakia, Gadigal). For the remaining 36 of those that collected ethnicity data (55%), variability was evident — for example, some binational registries recorded “Māori, Pacific Islander”, and others recorded non‐Indigenous ethnicity.

Governance representation

Many registries had governance or steering committees with a central role in overseeing processes and outputs for each registry. Membership generally consisted of clinicians, allied health specialists, researchers, funding bodies and consumers; however, only eight registries (7%) reported Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation on these committees through a specific identified role (Box 5), 87 (81%) did not have such representation, and this information was unknown for the remaining registries.

Registry ethics

A total of 94 registries (88%) provided details to the ARCR on governing bodies which had provided human research ethics committee (HREC) approval; the remaining 13 (12%) cited quality improvement initiatives for safety and quality, such as jurisdiction agreements or health care or hospital acts in place of ethics approvals (Supporting Information, table 1). Of the 94 registries which had sought ethics approval, 11 (12%) had sought approval through a state or territory AHREC for their registry in addition to their primary HREC approval. Of the 83 registries (78%) that did not have documented AHREC approval, 45 (54%) had sought approval from an HREC in a state which does not have a registered AHREC or similar body. In addition, 49 of these 83 registries (59%) recorded ethnicity status in their registries (Box 5).

Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive review of IG‐Data processes around quality indicator collection, ethics approval, and Indigenous representation on registry governance in Australian clinical registries. Our outcomes suggest that collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status is not a priority for clinical registries, with no data items for collection of Indigenous status in nearly 40% of registries. For international registries, this lack of data items may be attributable to legal requirements as it is not legally allowed to collect ethnicity status across Sámi, Ainu, Ryūkyūan and Kanak countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, France–New Caledonia, and Japan); however, this only affects 5% of registries in this study.11 The lack of appropriate data items may also be indicative of challenges to data quality in collection of ethnicity status for registries. Under‐identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status is well documented in administrative data collections (eg, censuses, taxation information, health records), which may influence the decision of a registry as to whether they collect ethnicity status.12,13,14 Improvements to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identification in administrative data have occurred through data linkage and application of enhancement or multistage algorithms by industry.12,14 These processes are costly and require specialised data science skills, which are not conceivable for many registries that are constrained by tight resourcing and often rely on the goodwill of staff in registry participation sites to upload this information as part of quality and safety reporting without additional resourcing.

Lack of reporting of Indigenous status in registries may also represent conceptualisation of health and wellbeing models from Western biomedical models of health, where quality indicators and patient care focus on clinical knowledge, and cultural nuances are precluded. These approaches do not recognise diversity or pluralism in health care journeys or relationality in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient experience.7,11 For these reasons, the Commission has redeveloped principles in their clinical quality registries framework through prioritising consumer engagement, particularly with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, in clinical design and outcome translation.2 In addition, recommendations in the National Clinical Quality Registry and Virtual Registry Strategy 2020–2030 call for prioritisation of identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in datasets.8 These recommendations support national initiatives to improve accuracy and completeness of ethnicity status in hospital medical records, which are often used for registries, through training of health care staff on the standard Indigenous question.7 However, further reforms are needed for accurate and reliable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health data analysis through community‐centric approaches, such as strength‐based analysis and community contextualisation to inform policy, clinical models of care, service responses and health services.15 Time will tell if further uptake of these national principles has long term impacts on recording and reporting of health care quality and effectiveness for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

For the 61% of registries which contained an ethnicity item, variation existed in coding of this item. Nearly 30% of registries that we audited coded their ethnicity item using national phrasing of “Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander”; however, no registries collected data at a regional, community or language group level. Other registries used collective phrasing of “Indigenous”, or even tautologies of “Indigenous Australian or Torres Strait Islander”. This ambiguity is indicative of white possessive logic in registry processes16 which is reflective of AHREC engagement — only 10% of registries had this approval. In addition, 49 of the registries that had sought ethics approval but not AHREC approval (59%) recorded ethnicity. While some of these registries may have approval in a jurisdiction without an AHREC or may not formally report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status, it does question integrity around ethics processes when working with Indigenous data. The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) provide six core values for research in this area (reciprocity, respect, equality, responsibility, survival and protection, and spirit and integrity);17,18 this does not preclude Indigenous data or registry work. Registries need to consider the significant role that they play in IG‐Data to work towards Indigenous data sovereignty.

In addition, the National Strategy for Clinical Quality Registries and Virtual Registries (2020–2030) provides priority actions to enhance quality and efficiency of systematic data collection through all registries having a “standard Indigenous status item”.8 However, no standard methods exist to support registries in developing meaningful and ethically appropriate ethnicity coding for Indigenous communities internationally and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities nationally. Our recommendation is for registries to work with Aboriginal organisations to co‐develop ethical data collection approaches, items and coding for ethnicity collection,7 which should include AHREC approvals. This might involve, for example, peak bodies (ie, the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, AIATSIS or Lowitja Institute) for binational and national registries, with AIATSIS ethics approval and AHREC approval across represented jurisdictions. These organisations are best placed in providing informed, ethical, community‐centric data governance approaches for Indigenous data. This may include cases where it is inappropriate for a clinical registry to collect ethnicity data at a language group level due to individual identification.

Data custodians of clinical registries have a responsibility to establish governance or steering committees who provide input into overarching strategies, policies and procedures, such as data access agreements or annual reporting.2,8 Representation on these governance or steering committees generally includes researchers, clinicians and patients or consumers. Recommendations from the Commission and Australian Government Department of Health and Age Care include identified roles for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander participants on these committees.2,8 However, despite these national recommendations, less than one in ten clinical registries had Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation. The invisibility of Indigenous knowledges at this level contributes and reinforces deficit discourses of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities against clinical quality indicators and outcome measures. The national recommendations, in part, act to disrupt these approaches and recognise the sovereign rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to data control, ownership and self‐determination, along with the responsibility of clinical registries to facilitate meaningful engagement and champion change.7,11,19 This should be further supported by registries enacting principles from the AIATSIS research code of ethics17 and the NHMRC Road Map 3 for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health through research.18

Limitations

Registration with the Commission's ARCR is purely voluntary, thus not all clinical quality registries in Australia may presently be registered. Despite this, to our knowledge, our study is the first to undertake a comprehensive audit of ARCR registries, focusing on IG‐Data processes. We hope that current clinical registries, and researchers and clinicians looking to establish registries, will find outcomes from this audit of use to guide their current work. Additional limitations of this study include the targeted focus of this audit on specific IG‐Data processes, in which specific statistical processes and reporting have not been examined. We note that five registries did not respond to interview requests. Since the time of our data collection, both desktop review and interviews, some registries may have added new items (eg, ethnicity status) to their registries or obtained AHREC approval, and more registries may have been added to the ARCR.

Conclusion

Indigenous governance of data is a key priority area for national government frameworks and strategies in Australia. However, there is significant variability across clinical quality registries in how IG‐Data is enacted or addressed. These approaches affect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, rendering communities invisible in policy, clinical models of care, health services and initiatives. It is clear that radical change is required to facilitate new meaningful approaches to clinical quality indicator development. This development must engage with peak stakeholders and community organisations with accountability in targeting health inequities for improvement in health outcomes.

Box 1 – Audit process and data collection steps

|

|

Sources, considerations, and steps for collecting data |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Part A: target registries identified |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Source |

Australian Register of Clinical Registries |

||||||||||||||

|

Demographics |

Condition, clinical domain, year established, geographical coverage, ethics approval |

||||||||||||||

|

AHREC coding |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Broad clinical domains |

Review and grouping of Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care‐defined conditions for each registry |

||||||||||||||

|

Clinical domain (Commission defined) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Part B: desktop review |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Sources |

Registry websites, annual reports, data dictionaries and other relevant registry documents available online |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity collection coding |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity coding |

Outlining how the ethnicity item is coded by registries (eg, “Indigenous Australian”) |

||||||||||||||

|

Governance representation |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Part C: phone interviews |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Sources |

Registry data custodians and/or administrators |

||||||||||||||

|

Recruitment |

Email invitation to phone interview, with follow‐up to participate conducted twice if no response |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity collection question |

Do you collect ethnicity data for patients in your registry? |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity coding question |

If you do collect this item, how is this item coded? |

||||||||||||||

|

Governance representation question |

Do you have Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation on your registry's governance or steering committee? |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AHREC = Aboriginal human research ethics committee; HREC = human research ethics committee. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Registry demographics

|

Type of registry |

Number (%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Geographical coverage |

|

||||||||||||||

|

International |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Binational between Australia and New Zealand |

40 (37%) |

||||||||||||||

|

National |

25 (23%) |

||||||||||||||

|

State |

26 (24%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Regional |

10 (9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

1 (1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Time since registry first started |

|

||||||||||||||

|

< 5 years |

29 (27%) |

||||||||||||||

|

5–10 years |

29 (27%) |

||||||||||||||

|

11–20 years |

26 (24%) |

||||||||||||||

|

> 20 years |

18 (17%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Broad clinical domain |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Asthma |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Blood, liver conditions |

8 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Cancer (high burden cancers or cancers) |

29 (27%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Cardiac, stroke, ischaemic heart disease |

11 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Critical care |

11 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Dementia |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Diabetes |

3 (3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Maternity |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Musculoskeletal disorders |

11 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other congenital or autoimmune condition |

7 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other specialised conditions or service |

4 (4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other surgery, anaesthetics or implant |

7 (7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Pain and rehabilitation |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Pelvic floor procedures, devices, endometriosis |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Trauma, burns, injury |

6 (6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Variation in ethnicity data item definition

|

|

Number (%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity data collected and/or reported* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

65 (61%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Indigenous status |

62 (58%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other ethnicities |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

33 (31%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

10 (9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity definition used for Indigenous status † |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal Islander |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

29 (47%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; Indigenous |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; Caucasian; Pacific Islander; Native American; Hispanic; Indian; Asian; African American; other |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; Oceanic First Peoples; culturally and linguistically diverse |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity (generic) |

3 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethnicity, Māori (NZ), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Indigenous |

8 (13%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Indigenous; culturally and linguistically diverse |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Indigenous Australian or Torres Strait Islander; Māori, Pacific Islander |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Indigenous or Torres Strait Islander; Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Māori (NZ), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

9 (15%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Māori (NZ), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; Caucasian; Pacific Islander; Native American; Hispanic; Indian; Asian; African American; other |

2 (3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Māori (NZ), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; First Nations; Oceanian (specified with Indigenous peoples [eg, Cook Island Māori, NZ Māori, Aboriginal Australian, Torres Strait Islander, Samoan]) |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Māori, Pacific Islander; Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

3 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander; Ethnicity–skin type: Australian Aboriginal; Anglo‐Saxon/Celtic; Arab/North African/Middle Eastern/Central Asian (eg, Lebanese, Turkish); Black African/Caribbean Islander; Māori/Pacific Islander; mixed skin type; Southern/South Eastern European (eg, Italian, Spanish, Maltese, Greek, Croatian); Western/Northern/Eastern European (eg, German, Danish, Polish); North East Asian (eg, Chinese, Japanese, Korean); South East Asian (eg, Vietnamese, Filipino); South Asian (eg, Indian, Pakistani); South American; other |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

NZ = New Zealand. * Denominator for calculation of percentages is 107 (total number of registries reviewed in the study). † Denominator for calculation of percentages is 62 (number of registries that collected and/or reported Indigenous status). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Inclusion of ethnicity analysed by geographical coverage, Indigenous representation and AHREC approval

|

|

Number of registries |

Number (%) of registries that included ethnicity |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Geographical coverage |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

International |

5 |

1 (20%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Binational |

40 |

24 (60%) |

|||||||||||||

|

National |

26 |

19 (73%) |

|||||||||||||

|

State |

26 |

19 (73%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Regional |

9 |

2 (22%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Indigenous representation on governance or steering committee |

8 |

8 (100%) |

|||||||||||||

|

AHREC approval |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

8 |

4 (50%) |

|||||||||||||

|

No |

33 |

16 (48%) |

|||||||||||||

|

No — no AHREC* |

50 |

34 (68%) |

|||||||||||||

|

No — other† |

7 |

6 (86%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

8 |

4 (50%) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AHREC = Aboriginal human research ethics committee; HREC = human research ethics committee. * HREC approval in Victoria, Queensland or Tasmania, where there is no state AHREC or similar. † Health care and/or hospital acts or other jurisdiction agreements precluded HREC approval requirements. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Received 8 September 2023, accepted 18 December 2023

- Courtney Ryder1,2

- Sadia Hossain1,3

- Leanne Howard4

- Julia Severin1

- Rebecca Ivers1,4

- 1 Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

- 2 Flinders Health and Medical Research Institute, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

- 3 Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW

- 4 UNSW Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Flinders University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Flinders University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

We acknowledge the traditional lands in which this manuscript was created and shaped (Eora, Kaurna Yerta, Bedegal, Gadigal and Darug) and pay respect to their Elders past, present and emerging.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Prioritised list of clinical domains for clinical quality registry development: final report. November 2016. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/resource‐library/prioritised‐list‐clinical‐domains‐clinical‐quality‐registry‐development‐final‐report (viewed Aug 2023).

- 2. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National arrangements for clinical quality registries. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our‐work/health‐and‐human‐research/national‐arrangements‐clinical‐quality‐registries (viewed Aug 2023).

- 3. Gong J, Singer Y, Cleland H, et al. Driving improved burns care and patient outcomes through clinical registry data: a review of quality indicators in the Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand. Burns 2021; 47: 14‐24.

- 4. Ryder C, Mackean T, Hunter K, et al. Equity in functional and health related quality of life outcomes following injury in children — a systematic review. Crit Public Health 2020; 30: 352‐366.

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework summary report January 2023. Canberra: AIHW, 2023.

- 6. Ryder C, Mackean T, Hunter K, et al. Yarning up about out‐of‐pocket healthcare expenditure in burns with Aboriginal families. Aust N Z J Public Health 2021; 45: 138‐142.

- 7. Diaz A, Soerjomataram I, Moore S, et al. Collection and reporting of Indigenous status information in cancer registries around the world. JCO Glob Oncol 2020; 6: 133‐142.

- 8. Australian Government Department of Health and Age Care. Maximising the value of Australia's clinical quality outcomes data: a national strategy for clinical quality registries and virtual registries 2020–2030. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/a‐national‐strategy‐for‐clinical‐quality‐registries‐and‐virtual‐registries‐2020‐2030?language=en (viewed Aug 2023).

- 9. Maiam nayri Wingara; Indigenous Data Sovereignty Summit 2023. Data for governance: governance of data [briefing paper]. Proceedings of the 2nd Indigenous Data Sovereignty Summit; Cairns, 13 August 2023.

- 10. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Australian Register of Clinical Registries. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/australian‐register‐clinical‐registries (viewed Jan 2021).

- 11. Balestra C, Fleischer L. Diversity statistics in the OECD: how do OECD countries collect data on ethnic, racial and indigenous identity? (OECD Statistics Working Paper No. 2018/09). Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018. https://www.oecd‐ilibrary.org/economics/diversity‐statistics‐in‐the‐oecd_89bae654‐en (viewed Aug 2023).

- 12. Christensen D, Davis G, Draper G, et al. Evidence for the use of an algorithm in resolving inconsistent and missing Indigenous status in administrative data collections. Aust J Soc Issues 2014; 49: 423‐443.

- 13. Griffiths K, Coleman C, Al‐Yaman F, et al. The identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in official statistics and other data: critical issues of international significance. Stat J IAOS 2019; 35: 91‐106.

- 14. Randall DA, Lujic S, Leyland AH, Jorm LR. Statistical methods to enhance reporting of Aboriginal Australians in routine hospital records using data linkage affect estimates of health disparities. Aust N Z J Public Health 2013; 37: 442‐449.

- 15. Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet–Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): a population study. Lancet 2016; 388: 131‐157.

- 16. Ryder C, Holland AJA, Mackean T, et al. In response to “Driving improved burns care and patient outcomes through clinical registry data: a review of quality indicators in the Burns Registry of Australia and New Zealand”. Burns 2022; 48: 477‐479.

- 17. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. AIATSIS Code of Ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research. Canberra: AIATSIS, 2020. https://aiatsis.gov.au/research/ethical‐research/code‐ethics (viewed Jan 2022).

- 18. National Health and Medical Research Council. Road Map 3: a strategic framework for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health through research. June 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about‐us/publications/road‐map‐3‐strategic‐framework (viewed Jan 2022).

- 19. Ryder C, Wilson R, D'Angelo S, et al. Indigenous data sovereignty and governance: the Australian Traumatic Brain Injury National Data Project. Nat Med 2022; 28: 888‐889.

Abstract

Objectives: To examine Indigenous Governance of Data processes in Australian clinical registries.

Design, setting, participants: Audit (via desktop review and interviews) of registries in the Australian Register of Clinical Registries from 17 January 2022 to 30 April 2023.

Main outcome measures: The number of clinical registries collecting ethnicity data, reporting Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation on registry governance or steering committees, and reporting human research ethics committee approval.

Results: A total of 107 clinical registries were reviewed. Of these registries, 65 (61%) collected ethnicity data; when these were grouped by geographical coverage, those most likely to collect ethnicity data were binational (24/40 [60%]), national (19/26 [73%]) or state based (19/26 [73%]). Of the registries that collected ethnicity data, 29 (45%) classified their ethnicity item as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Only eight clinical registries (7%) reported Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander representation on their governance or steering committees. Human research ethics approval was reported in 94 registries (88%), with only 11 (12%) having Aboriginal human research ethics committee approval.

Conclusion: Significant variability is evident in clinical registry recording of Indigenous governance of data, meaning that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities remain invisible in data which is used to inform policy, clinical models of care, health services and initiatives. Radical change is required to facilitate meaningful change in quality indicators for clinical registries nationally.