The known: The disproportionate numbers of Aboriginal people who come into contact with the justice system or die by suicide are major public health problems and the focus of Closing the Gap targets.

The new: A culturally informed program co‐developed with Aboriginal people improved the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal women preparing to leave prison in Perth, and reduced their psychological distress.

The implications: Our findings have implications for prison reform, may have economic and social justice benefits, and could contribute to improved clinical practice and health care for Aboriginal people in justice system facilities. Improving their social and emotional wellbeing could help reduce the number of Aboriginal people in Australian prisons by reducing recidivism.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have great strengths and resilience and have the longest continuing cultures in the world, with more than 65 000 years of history. However, colonisation and government policies have contributed to ongoing systemic discrimination. As a result of colonial oppression, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people today experience disadvantages across health, housing, education, and employment,1 and are over‐represented in criminal justice systems.2

The landmark Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody3 led to 339 recommendations, many concerning the disproportionate number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prison. A subsequent inquiry2 recommended that the “unique systemic and background factors” be considered when sentencing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders (recommendation 6‐1). More than 30 years since the Royal Commission, the disproportionate number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the justice system remains a national concern and a priority in the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.4 However, closing the gap in justice outcomes will fail without fundamental change, including the prioritisation of Aboriginal‐led and culturally informed healing programs.2,5

Western Australia has the highest Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander imprisonment rates: 3598 per 100 000 adults (national rate: 2269 per 100 000 adults).6 Further, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women comprise one of the fastest growing groups in the Australian prison system;7 in the ten years to 2021, 78% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander female prisoners had prior imprisonments, compared with 30% of other female prisoners.8 The high incarceration and recidivism rates can be attributed to a range of disadvantages and oppression arising from colonisation, including historical, political, and social factors. Culturally informed in‐prison rehabilitation programs that strengthen the wellbeing and promote the healing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are needed.

The Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program9 was co‐developed with a cultural framework by Aboriginal psychologists and community co‐researchers. It is based on the Social and Emotional Wellbeing model,10 which departs from the medicalised Western model of wellbeing. The Social and Emotional Wellbeing model is a strengths‐based and holistic health framework developed by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. It reflects the dynamic and complex relationships between the self, the seven domains of wellbeing, and historical, political, cultural, and social determinants of health, as experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is inextricably linked with connections to the seven interrelated and overlapping domains of the Social and Emotional Wellbeing model (Box 1); disharmony in these relations is a risk for wellbeing.

The Program has been delivered in three urban communities in Western Australia and two rural communities in Queensland. After participating in the Program, community members reported reduced psychological distress, improved relationships with families and communities, strengthened social support networks, and enhanced self‐confidence and resilience.11 Other positive outcomes included strengthening and celebrating Aboriginal culture, learning parenting and communication skills, and feeling empowered.11 Despite such success, the Program has not been used or evaluated in the justice system.

The Program is the first Aboriginal‐led, in‐prison program in Western Australia that specifically aims to enhance social and emotional wellbeing and promote healing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. We are aware of only two Aboriginal‐led in‐prison programs in Western Australia that have been evaluated; they target alcohol and substance misuse, and work training, and have reported reduced recidivism rates.12

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impacts of the Program in the prison system, and to ascertain whether the positive effects reported by community members11 are also reported by Aboriginal women who complete the Program during the pre‐release period. It was expected that participating in the Program would reduce psychological distress and enhance the social and emotional wellbeing of pre‐release Aboriginal women.

Methods

We adopted an Aboriginal Participatory Action Research (APAR) methodology.13 The APAR is a strengths‐based and culturally appropriate approach that privileges participation by the relevant community, based on their collective experience and social history. The authorship team consisted of senior Aboriginal researchers (first and last authors) and early to mid‐career Aboriginal and non‐Aboriginal researchers under the guidance of the first and last authors, working within Aboriginal‐led organisations. We acknowledge and pay respect to the traditional custodians of Noongar Boodja. We pay respects to Elders past and present, and acknowledge the strengths and resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This research is guided by the national statement on ethical research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples14 and the Consolidated Criteria (CONSIDER) for reporting of health research involving Indigenous Peoples (Supporting Information).15

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the Boronia Pre‐Release Centre for Women, Perth, were invited (through promotional flyers and at an information session) to participate in the Program (two days per week for six weeks), and to evaluate it at the end of the Program. This is an interactive program involving presentations, workshops, activities, group discussions and self‐reflections. It is designed to enhance social and emotional wellbeing, resilience and strengthen relationships, and reduce levels of psychological distress and suicide. The content of the Program is based on three main modules: the Self, Family and Community. The first delivery of the Program in a justice system facility during May – July 2021 was initiated by Aboriginal women from the Langford Aboriginal Association in response to the needs of the community. Evaluation of the delivery, including data analyses and interpretation, was led and governed by the first author, who led the National Empowerment Project from which the Program was developed.16 A community reference group convened by the Langford Aboriginal Association met regularly before, during and after Program delivery. This project privileged the voices of Aboriginal co‐researchers; for example, the views of Aboriginal co‐researchers were prioritised during data coding, and a strengths‐based analysis was adopted.

Measures

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K‐5)17 was used to assess participants’ psychological distress at the first and last Program sessions. The K‐5 has been validated with Aboriginal communities and is a culturally modified assessment tool.18 It consists of five items that measure the frequency of psychological distress during the preceding four weeks on a 5‐point Likert scale (from 1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time). A total score of 5–11 was deemed to indicate a moderate level, 12–25 a high level of psychological distress. We conducted a paired sample t test and correlation of pre‐ and post‐Program K‐5 scores.

The “stories of most significant change” technique19 was used to assess the outcomes of the Program from the individual perspective. On completion of the Program, participants wrote the most significant change they had experienced during the Program, explained why it was significant, and provided a title for their story. This measure privileges the voices and world views of participants.

We undertook an adapted reflexive thematic analysis of the stories of most significant change to examine the success factors and mechanisms of change of the Program (Supporting Information). Reflexive thematic analysis is inductive; themes are extracted from the qualitative data by coders,20 precluding determination of themes beforehand. Two independent thematic analyses were conducted by four coders working in pairs to ensure rigour during the reflexive thematic analysis. One pair of non‐Aboriginal coders, researchers in the Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention, were supervised by the Aboriginal centre director. The other pair of coders, an Aboriginal facilitator and a Program administrative support staff member, were present during Program delivery at the Boronia Centre. The final thematic map was developed by consensus among the four coders.

Positionality

Pat Dudgeon AM is from the Bardi people and is the director of the Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention at the University of Western Australia. Her research focus is Indigenous social and emotional wellbeing and suicide prevention. She is also the lead chief investigator of a national research project, Transforming Indigenous Mental Health and Wellbeing, that aims to develop approaches to Indigenous mental health services that promote cultural values and strengths as well as empowering users. She is a board member of Gayaa Dhuwi (Proud Spirit) Australia, a prominent contributor to the Australian Indigenous Psychologists Association, and a member of Advisory Group to the National Office of Suicide Prevention. She was also the co‐chair of the National Ministerial Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Advisory Group, where significant policies have been developed to improve the mental health and wellbeing of Indigenous Australians.

Ee Pin Chang has Chinese heritage and moved to Whadjuk Country to pursue studies in psychology. Her research focuses on enhancing social and emotional wellbeing of justice‐involved Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Joan Chan has Chinese heritage and moved to Whadjuk Country ten years ago. She works to identify best practice Indigenous suicide prevention programs and services.

Carolyn Mascall has connections to Yinggardu Country and lives on Wadjuk Boodjar where she works to further cultural, social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Gillian King is from Noongar/Gurindji people and facilitates the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program in the Boronia Centre, with Langford Aboriginal Association, to empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Jemma Collova has Italian heritage, was born on Whadjuk Country, and currently lives on Miriwoong Country. She is continuing to decolonise her worldview and research approach.

Angela Ryder AM is a proud Wilman/Goreng Noongar woman, a mother and grandmother. Her research focus is Aboriginal cultural, social, and emotional wellbeing.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC875), the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (RA/4/1/5299), and the Western Australian Department of Justice Research Application and Advisory Committee (ID474). Participants provided informed consent to the evaluation stage of the project after reading the participant information form by signing a participant consent form.

Results

Fourteen of the 16 Aboriginal women at the Boronia Centre agreed to participate and completed the Program, ten of whom completed the evaluation (mean age, 37.2 years; standard deviation [SD], 7.8 years). Mean psychological distress after the Program (K‐5 score: 9.0 [SD, 3.5]; 95% confidence interval [CI], 6.5–11.5) was lower than before the Program (11.3 [SD, 3.3]; 95% CI, 9.0–13.6; P = 0.047). The effect size was medium (Cohen d = 0.59), but the correlation of pre‐ and post‐Program K‐5 scores was not statistically significant (r = 0.35, P = 0.33).

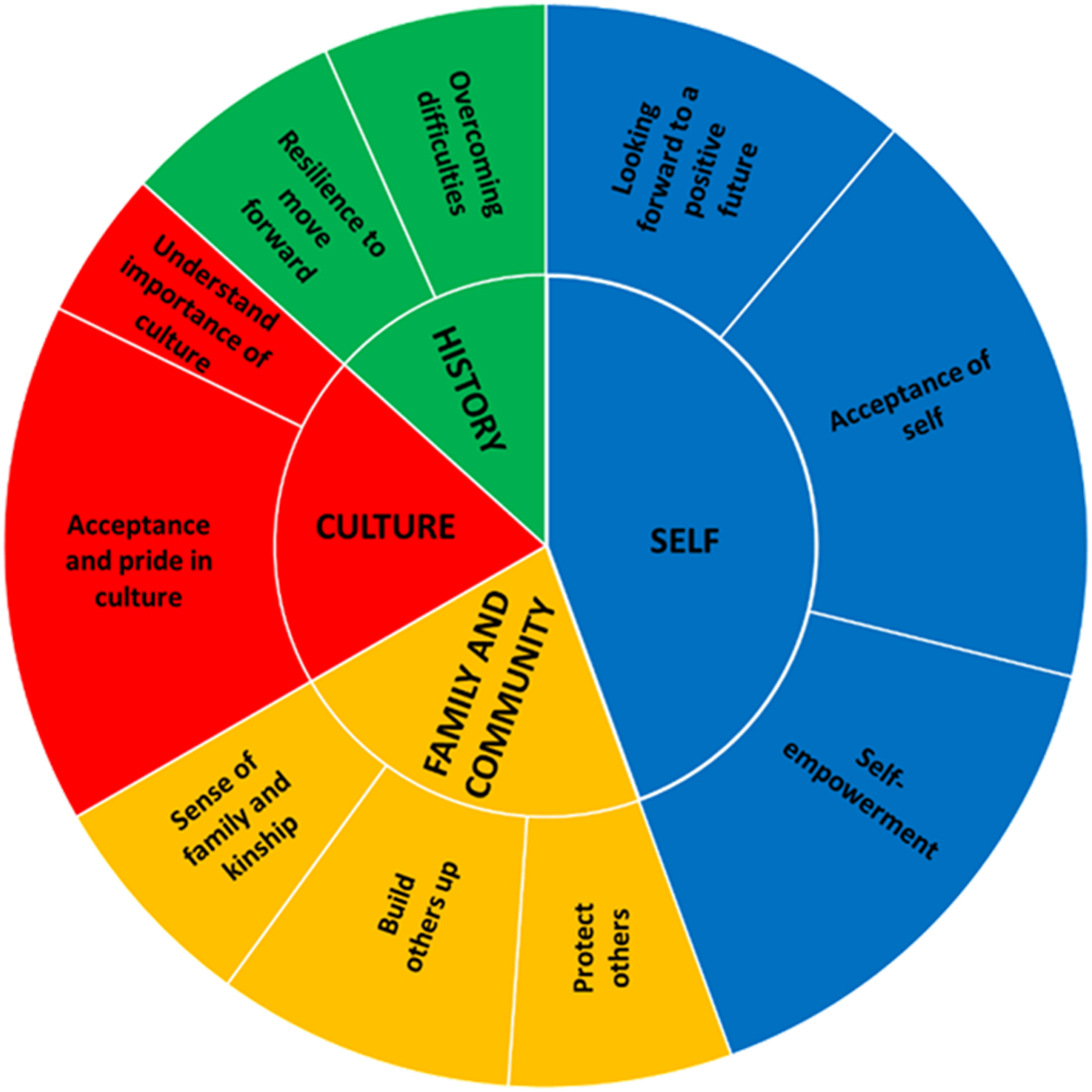

Four overarching themes, with ten sub‐themes, emerged from thematic analysis of the stories of most significant change (Box 2; Box 3). “History” (two sub‐themes: overcoming difficulties; resilience to move forward) reflects the courage to acknowledge the difficulties participants experienced. Both sub‐themes were consistent with the findings of the earlier program evaluation workshops. Acknowledging one's history and past promotes healing and recovery,11 and underlies the strengths and resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples throughout history.

The theme “self” (three sub‐themes: acceptance of self; looking forward to a positive future; self‐empowerment) corresponds to “self” as reported in the Program community evaluation workshops.11 Despite traumatic and challenging pasts, participants described renewed hope for the future, feeling empowered by participation in the Program. They expressed a desire to educate themselves. In turn, they experienced confidence in seeing positive change, and excitement associated with “a new chapter of my life”. Endorsed by all participants, this theme was the strongest to emerge; eight participants endorsed at least two of the three sub‐themes. This suggests that the Program was effective in empowering the women and enhancing their self‐determination, contributing to reduced psychological distress by enhancing their self‐esteem and cultural identity. This sense of empowerment led participants to experience a desire to reconnect with families, communities, and culture, reflecting an innate motivation and desire for cultural continuity.21

The theme “culture” (two sub‐themes: acceptance and pride in culture; understanding the importance of culture) reflects the importance of connection to culture, an outcome of the National Empowerment Project from which the Program was developed.16 Participants expressed acceptance of and pride in culture and Aboriginality. Culture is also a recurring theme in other investigations of the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.2,10,11,22,23 The concept of cultural continuity has been defined as the maintenance of cultural identity through mechanisms by which members of its community maintain cultural practices.24 For Indigenous peoples, cultural continuity can protect against uncertainty by grounding individuals in an identity associated with long standing, meaningful cultural practices and rich histories that provide guidelines for navigating the world.25 Strengthening cultural identity protects against psychological distress, reduces the risk of suicide, and promotes social and emotional wellbeing across all Indigenous groups and ages.21,26 Connection to culture is therefore an effective, strengths‐based approach to promoting social and emotional wellbeing, reduces psychological distress in Indigenous peoples, particularly those directly affected by colonisation and forcibly removed from their homes,27 disrupting connection to family and community.

The theme “family and community” (three sub‐themes: a sense of family and kinship; build others up; protect others) corresponds to two domains of the Social and Emotional Wellbeing model of health framework (family and community), reflecting the collectivist perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.16 Having been empowered, participants became aware of their roles in the family and community (eg, as parents) and wanted to fulfil these roles by sharing cultural knowledge, teaching life lessons, and protecting their children. Connections to family and community underpin social and emotional wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture.11 A strong healthy connection to family and community fosters a greater sense of self and resilience, contributing to improvements in other determinants of health, including education, employment, and community safety, as highlighted in the implementation plan of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023.28

Discussion

We evaluated the effects of the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program for Aboriginal women at the Boronia Pre‐Release Centre for Women in Perth. The stories offered by the women indicated that participating in the Program was associated with positive, empowering changes in their perceptions of history, culture, family and community, and themselves, consistent with the findings of an evaluation of the Program delivered in the community.11 These changes were accompanied by a reduction in the mean level of self‐reported psychological distress.

Our findings provide preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of the Program for empowering Aboriginal women preparing to re‐enter the community from prison, with practical implications. First, our findings provide important insights into a high priority problem and two targets of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap: the disproportionate number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who have contact with the criminal justice system, and the need to improve the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to reduce the risk of suicide. Specifically, the stories revealed that the women were deprived of truth‐telling as a powerful healing tool. Our findings highlight the power of programs that facilitate truth‐telling in culturally safe spaces while strengthening wellbeing. Truth‐telling should also be undertaken in other settings (eg, in schools) to reduce the risk of contact with the justice system. Our findings also indicate that incarceration disrupts social and emotional wellbeing connections, including connections with family and community, and with Country. Programs that aim to restore these connections can be preventive and restorative justice approaches by strengthening the resilience of the women. However, it is important to consider how Closing the Gap targets can be reached after the outcome of the Voice referendum, as Australians see the undoing of promising reform made.

Second, our findings provide preliminary evidence about the potential of the Program to respond to several recommendations of the Pathways to Justice Report.2 Specifically, the Program is trauma‐informed and strives for cultural appropriateness; as it was “developed with and delivered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women”, it could reduce recidivism in this group (recommendation 11‐1). The Program could be offered as a pre‐ or post‐release program to facilitate the reintegration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people into their communities (recommendation 9‐1), and as a parole condition, instead of short sentences, to increase the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners released on parole (recommendation 9‐2). Further research is needed to assess the effectiveness of the Program for facilitating the reintegration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, before and after their release from prison, and for reducing recidivism in the longer term by reducing psychological distress, enhancing social and emotional wellbeing, and responding to the social and cultural determinants of health. Our findings highlight the importance of culturally informed programs developed for and by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, adopting best practice principles that acknowledge the Aboriginal ways of knowing, being, and doing.29,30

Limitations

Our small sample size, and the fact that women at Boronia Centre may not be representative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in mainstream prisons, means that our findings may not be generalisable to other justice facilities; our study should be replicated with a larger number of participants. Further, the reduction in mean psychological distress should be interpreted with caution. The K‐5 is time‐sensitive and may be influenced by recent life events (negative or positive). Future studies could evaluate whether such reductions are sustained beyond the end of the Program. Finally, evaluations of the effectiveness of programs and services with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would benefit from broadening the outcomes assessed and going beyond evidence‐deficit narratives by embedding culturally appropriate assessment tools and methodologies.13

Conclusion

We report the first evaluation of the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program delivered in a justice system facility. The preliminary evidence suggests that it is effective for enhancing protective factors that promote social and emotional wellbeing and reduce psychological distress in Aboriginal women in contact with the justice system. Our findings have implications for prisons reform, could have economic and social justice benefits, and provide insights into effective health care policy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who come in contact with the justice system.

Box 1 – The social and emotional wellbeing model that forms the basis of the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people*

* Adapted, with permission, from reference 10.

Box 2 – Thematic map of the stories of most significant change provided by the ten women who participated in the evaluation of their experience of the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program at the Boronia Pre‐Release Centre for Women in Perth*

* The size of each pie chart slice represents the number of women who endorsed the theme or sub‐theme

Box 3 – Representative quotes from the stories of most significant change provided by the ten women who participated in the evaluation of their experience of the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program at the Boronia Pre‐Release Centre for Women in Perth

|

Theme/sub‐theme |

Illustrative quotes |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

History |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Overcoming difficulties |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Resilience to move forward |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Self |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Acceptance of self |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Looking forward to a positive future |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Self‐empowerment |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Culture |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Acceptance and pride in culture |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Understanding the importance of culture |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Family and community |

|

||||||||||||||

|

A sense of family and kinship |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Build others up |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Protect others |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Received 26 October 2023, accepted 7 May 2024

- Pat Dudgeon (Bardi)1,2

- Ee Pin Chang2,3

- Joan Chan2

- Carolyn Mascall4,5

- Gillian King (Noongar)5

- Jemma R Collova2

- Angela Ryder (Noongar)4,5

- 1 Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, the University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 2 Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention, the University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 3 Suicide Prevention Australia, Sydney, NSW

- 4 Aboriginal Services Relationships Australia Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 5 Langford Aboriginal Association, Perth, WA

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Western Australia, as part of the Wiley – the University of Western Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data sharing:

The study participant information form and participant consent form will be available for sharing upon email request to the corresponding author after publication. Individual participant data will not be available for sharing.

The Psyche Foundation (https://www.psychefoundation.org) provided grant funding for this research project. The Psyche Foundation did not have any influence on the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, reporting or publication of this article. We also acknowledge the participation and assistance of the Western Australia Department of Justice in our project. This report has not been endorsed by the Department, nor is it an expression of the policies or views of the Department. Any errors of omission or commission are the responsibility of the research team at the Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention. To our knowledge, the following references report Indigenous‐led research: 1, 7, 9‐11, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21‐25, 29, 30.

Ee Pin Chang is funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from Suicide Prevention Australia. Suicide Prevention Australia did not have any influence on the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, reporting or publication of this article. Pat Dudgeon is partly supported by the Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, Perth.

We acknowledge the knowledge, courage, and generosity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, families, and communities who contributed to this project with their honest and open sharing of their experiences.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Milroy H, Watson M, Kashyap S, Dudgeon P. First Nations peoples and the law. Australian Bar Review 2021; 50: 510‐522.

- 2. Australian Law Reform Commission. Pathways to justice: an inquiry into the incarceration rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (ALRC Report No 133). Dec 2017. https://www.alrc.gov.au/publication/pathways‐to‐justice‐inquiry‐into‐the‐incarceration‐rate‐of‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐peoples‐alrc‐report‐133 (viewed Oct 2022).

- 3. Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Reports. Updated 29 Apr 1998. https://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/IndigLRes/rciadic (viewed Oct 2022).

- 4. National Agreement on Closing the Gap. July 2020. https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national‐agreement (viewed June 2022).

- 5. Productivity Commission, Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Study report, volume 1. Jan 2024. www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/closing‐the‐gap‐review/report/closing‐the‐gap‐review‐report.pdf (viewed Feb 2024).

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Corrective Services, Australia, March quarter 2022. 9 June 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime‐and‐justice/corrective‐services‐australia/mar‐quarter‐2022 (viewed Oct 2022).

- 7. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner. Walking with the women: addressing the needs of Indigenous women exiting prison. In: Social Justice Report 2004; pp. 11‐66. https://humanrights.gov.au/our‐work/social‐justice‐report‐2004‐chapter‐2‐walking‐women‐addressing‐needs‐indigenous‐women (viewed Oct 2022).

- 8. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Prisoners in Australia, 2021 [here: table 29]. 9 Dec 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/crime‐and‐justice/prisoners‐australia/2021 (viewed Oct 2022).

- 9. Transforming Indigenous Mental Health and Wellbeing. Fact sheet B. The National Empowerment Project (NEP): Cultural, Social, and Emotional Wellbeing (CSEWB) Program. https://timhwb.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2021/09/CSEWB‐Full‐Doc.pdf (viewed Feb 2024).

- 10. Gee G, Dudgeon P, Schultz C, et al. Social and emotional wellbeing and mental health: an Aboriginal perspective. In: Dudgeon P, Milroy H, Walker R, editors. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Second edition. Canberra, 2014; pp. 55‐68. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/globalassets/media/documents/aboriginal‐health/working‐together‐second‐edition/working‐together‐aboriginal‐and‐wellbeing‐2014.pdf (viewed Feb 2024).

- 11. Dudgeon P, Derry KL, Mascall C, Ryder A. Understanding Aboriginal models of selfhood: the national empowerment project's cultural, social, and emotional wellbeing program in Western Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 4078.

- 12. Justice Reform Initiative. The need for alternatives to incarceration in Western Australia. Mar 2023. https://assets.nationbuilder.com/justicereforminitiative/pages/337/attachments/original/1681695603/9_JRI_Alternatives_WA_Full_V4_FINAL.pdf?1681695603 (viewed Feb 2024).

- 13. Dudgeon P, Bray A, Darlaston‐Jones D, Walker R. Aboriginal participatory action research: an Indigenous research methodology strengthening decolonisation and social and emotional wellbeing. Sept 2020. https://www.lowitja.org.au/page/services/resources/Cultural‐and‐social‐determinants/mental‐health/aboriginal‐participatory‐action‐research‐an‐indigenous‐research‐methodology‐strengthening‐decolonisation‐and‐social‐and‐emotional‐wellbeing (viewed Oct 2022).

- 14. National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Aug 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about‐us/resources/ethical‐conduct‐research‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐peoples‐and‐communities (viewed Feb 2024).

- 15. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 16. Dudgeon P, Cox A, Walker R, et al. Voices of the people: the national empowerment project. National summary report 2014: promoting cultural, social and emotional wellbeing to strengthen Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265786292_Voices_of_the_Peoples_The_National_Empowerment_Project_National_Summary_Report_2014_Promoting_cultural_social_and_emotional_wellbeing_to_strengthen_Aboriginal_and_Torres_Strait_Islander_communities (viewed Oct 2022).

- 17. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Measuring the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Jan 2009. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/5b75be10‐49ee‐4d9c‐baf0‐5092936c585e/msewatsip.pdf?v=20230605180910&inline=true (viewed May 2024).

- 18. Brinckley MM, Calabria B, Walker J, et al. Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of a culturally modified Kessler scale (MK‐K5) in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 1111.

- 19. Davies R, Dart J. The “most significant change” (MSC) technique. A guide to its use. Apr 2005. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275409002_The_‘Most_Significant_Change’_MSC_Technique_A_Guide_to_Its_Use (viewed Oct 2022).

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 2021; 18: 328‐352.

- 21. Chandler MJ, Lalonde C. Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada's First Nations. Transcult Psychiatry 1998; 35: 191‐219.

- 22. Dudgeon P, Bray A, Blustein S, et al. Connection to community. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 25 Mar 2022. https://www.indigenousmhspc.gov.au/publications/connection‐to‐community#:%20~:%20text=Connections%20to%20community%20are%20an,identity%20which%20can%20reduce%20suicide (viewed Oct 2022).

- 23. Edwige V, Gray P. Significance of culture to wellbeing, healing and rehabilitation. Bugmy Bar Book, 2021. https://www.publicdefenders.nsw.gov.au/Documents/significance‐of‐culture‐2021.pdf (viewed Oct 2022).

- 24. Auger MD. Cultural continuity as a determinant of Indigenous peoples’ health: a metasynthesis of qualitative research in Canada and the United States. Int Indig Policy J 2016; 7: 3.

- 25. Arabena K. “Country can't hear English”: a guide supporting the implementation of cultural determinants of health and wellbeing with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Karabena Consulting, 27 June 2020. https://www.karabenaconsulting.com/resources/country‐cant‐hear‐english (viewed Oct 2022).

- 26. Gibson M, Stuart J, Leske S, et al. Suicide rates for young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: the influence of community level cultural connectedness. Med J Aust 2021; 214: 514‐518. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/214/11/suicide‐rates‐young‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐people‐influence

- 27. Australian Human Rights Commission. Bringing them home report. Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Apr 1997. https://humanrights.gov.au/our‐work/bringing‐them‐home‐report‐1997 (viewed Oct 2022).

- 28. Department of Health and Aged Care. Implementation plan for the national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2013–2023. 2015; updated 15 Dec 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/implementation‐plan‐for‐the‐national‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐plan‐2013‐2023 (viewed June 2022).

- 29. Dudgeon P, Milroy J, Calma T, et al. Solutions that work: what the evidence and our people tell us. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide prevention evaluation project. University of Western Australia, Nov 2016. https://www.atsispep.sis.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2947299/ATSISPEP‐Report‐Final‐Web.pdf (viewed Oct 2022).

- 30. Jones J, McGlade H, Davison S. Traditional Aboriginal healing in mental health care, Western Australia. In: Danto D, Zangeneh M, editors. Indigenous knowledge and mental health: a global perspective. Cham: Springer, 2022; pp. 241‐253.

Abstract

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of the Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program for reducing psychological distress and enhancing the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal women preparing for release from prison.

Study design: Mixed methods; qualitative study (adapted reflexive thematic analysis of stories of most significant change) and assessment of psychological distress.

Setting, participants: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women at the Boronia Pre‐release Centre for Women, Perth, Western Australia, May and July 2021.

Intervention: Cultural, Social and Emotional Wellbeing Program (two days per week for six weeks). The Program involves presentations, workshops, activities, group discussions, and self‐reflections designed to enhance social and emotional wellbeing.

Main outcome measures: Themes and subthemes identified from reflexive thematic analysis of participants’ stories of most significant change; change in mean psychological distress, as assessed with the 5‐item Kessler Scale (K‐5) before and after the Program.

Results: Fourteen of 16 invited women completed the Program; ten participated in its evaluation. They reported improved social and emotional wellbeing, reflected as enhanced connections to culture, family, and community. Mean psychological distress was lower after the Program (mean K‐5 score, 11.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 9.0–13.6) than before the Program (9.0; 95% CI, 6.5–11.5;P = 0.047).

Conclusion: The women who participated in the Program reported personal growth, including acceptance of self and acceptance and pride in culture, reflecting enhanced social and emotional wellbeing through connections to culture and kinship. Our preliminary findings suggest that the Program could improve the resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander in contact with the justice system.