Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) affect 3–10% of all pregnancies globally.1,2,3 In Australia and New Zealand, 3–4% of pregnancies are affected by preeclampsia, a type of HDP that is associated with significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality.4,5,6,7 More recently, studies have demonstrated that HDP, particularly preeclampsia, are also associated with long term comorbid conditions in affected women and their offspring.8

The Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) was established in 2005, through amalgamation of the Australasian Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ASSHP) and the Obstetric Medicine Group of Australasia (OMGA), and is committed to providing up‐to‐date guidance to improve maternal and obstetric outcomes in pregnant women with medical disorders. This guideline represents an update of the SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014.9 Knowledge has advanced significantly since publication of the last guideline and newer evidence has allowed for recommendations on screening for women who are at risk of developing preeclampsia, preventive interventions, and clinical use of angiogenic biomarkers.

Methods

The methodology for the guideline was developed in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) standards for guidelines10 and was approved by NHMRC in December 2023, under section 14A of the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992. Detailed description of the methodology is accessible through the main guideline document and published methodology.11 Key stages included:

- establishing an expert multidisciplinary group of 28 members, comprised of a broad range of medical practitioners (obstetricians, primary care, intensive care, subspecialty physicians, and neonatologists), midwives, scientists, pharmacists, methodologists, First Nations People and consumer representatives;11

- identifying 39 clinical questions of priority, within the categories of screening, prevention and management;

- comprehensive literature searches for studies from 1970 to 2022, based on pre‐determined MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) keywords, through three main electronic databases (Medline, Cochrane Library, Embase);

- data extraction of selected literature, conducted independently by two members of the working group;

- meta‐analyses of extracted data through Review Manager 5.4 (RevMan; the Cochrane Collaboration, 2020; https://revman.cochrane.org/info);

- bivariate model analyses for sensitivity and specificity for diagnostic test accuracy through STATA18 (StataCorp);

- quality of evidence appraisal through the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach;12 and

- generation of recommendations based on the Evidence to Decision framework.13

Final recommendations were made with more than 60% of group members in agreement. The draft guideline was open for public consultation for six weeks, with 94 resulting comments addressed and incorporated into the guideline where appropriate.

Recommendations in the guideline are presented as either evidenced‐based recommendations or practice points.11 The main guideline document contains summary of meta‐analyses, rationale for recommendations and comparison of recommendations with key national and international guidelines. The guideline along with clinician and multilingual patient information sheets are accessible online at https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/.11

The recommendations are based on literature published up to December 2022. Where indicated, the working group may update meta‐analyses and recommendations based on critical new data. Updates following publication of this guideline can be accessed through the SOMANZ website.11

Summary of recommendations

The recommendations are presented in eight parts and include definitions of HDP, screening for women at risk, and preventive and management strategies.

Part 1: definitions of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Recommendations on definitions of HDP are largely consistent with the previous version of this guideline and are based on expert consensus.9 New to the guideline is the definition of masked hypertension.

Hypertension in pregnancy is defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg. These measurements should be confirmed by repeated readings (with three consecutive readings at least two minutes apart) within a minimum of four hours to confirm true hypertension. Accurate blood pressure measurement is important, as inaccuracies may result in variation of treatment.11

The recommended classifications of HDP are described in Box 1. Important updated points include the following:11

- proteinuria is a commonly recognised feature of preeclampsia but is not a mandatory criterion for the diagnosis of preeclampsia (refer to “Part 4.1: urine assessment for proteinuria” for more information); and

- at the time of publication, there remain limited data on inclusion of angiogenic markers as a diagnostic criterion for preeclampsia (refer to “Part 4.2: use of sFlt‐1/PlGF ratio” for more information).

The following investigations should be performed as part of the initial assessment of new onset hypertension (Practice point):

- full blood count — additional investigations for disseminated intravascular coagulation and/or haemolysis (coagulation studies, blood film, lactate dehydrogenase and fibrinogen) should be considered for significant thrombocytopenia or a rapid decline in haemoglobin concentration;

- electrolytes, urea and creatinine;

- liver function tests;

- proteinuria assessment — a dipstick assessment for proteinuria is clinically useful, readily available and easy to perform as an initial screening tool; however, where there is clinical suspicion for a HDP, a quantitative urine analysis (ie, urinary protein to creatinine ratio [uPCR]) should be performed (refer to “Part 4.1: urine assessment for proteinuria” for more information);

- angiogenic markers (eg, soluble fms‐like tyrosine kinase‐1 [sFlt‐1] to placental growth factor [PlGF] ratio) with a cut‐off < 38 can help rule out preeclampsia in women with clinical suspicion of preeclampsia after 20 weeks’ gestation and, if locally available, in a timely manner (refer to “Part 4.2: use of sFlt‐1/PlGF ratio” for more information);

- fetal assessment — ultrasound assessment for fetal growth, amniotic fluid volume (using amniotic fluid index or deepest vertical pocket), and umbilical artery Doppler; and

- cardiotocography assessment may be indicated according to hospital policy and gestation.

Following the diagnosis of a HDP, subsequent investigations and management of the diagnosed HDP should be undertaken as recommended in the main guideline document.11

Part 2: screening for women at risk of preeclampsia

Women should have their risk of preeclampsia assessed early in pregnancy to allow for consideration of preventive strategies (1B). There are clinical factors that may help in identifying women who are or who are not at increased risk of developing preeclampsia (Box 2). Risk assessment can be refined using combined first trimester screening (combined algorithm of maternal characteristics, biomarkers and sonographic assessment) (2B).

Where there are conflicting risk assessments based on clinical factors and combined first trimester screening, clinicians should discuss the risks and potential benefits of preventive strategies with women through a shared, informed decision‐making process.

At the time of publication, there were no published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the clinical use of combined first trimester screening, and the recommendations made were based on a diagnostic test accuracy assessment of 11 cohort studies. Furthermore, at the time of publication, combined first trimester screening is not widely accessible across Australia and New Zealand. The group acknowledges that there are ongoing studies on this topic and current recommendations are subject to review based on future updated data.

Part 3: prevention of preeclampsia

The recommendations on 14 pharmacological and two non‐pharmacological preventive interventions were made based on 118 RCTs (Box 3).

In summary, we recommend that 150 mg of oral aspirin (1B) at bedtime (2C) is commenced before 16 weeks’ gestation (1B) in women who have been identified at high risk of developing preeclampsia (Box 3). We recommend ceasing aspirin between 34 weeks’ gestation and birth (2B). The guideline includes an infographic that can be used to counsel women on the use of aspirin in pregnancy.11 We also recommend the use of supplemental calcium in women with a dietary calcium intake of less than 1 g per day (1C). The guideline includes a summarised dietary calcium intake calculator that can be used to ascertain women's dietary calcium intake.11 In addition to aspirin and supplemental calcium, moderate intensity exercise, in the form of aerobic, stretching and/or muscle resistance exercises, for a total of 2.5 to five hours a week, is recommended (Box 3) (2D). This guideline includes an infographic on exercising in pregnancy.11 At the time of publication, there remain inadequate data on the benefit of other pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions examined.11

Part 4: diagnosis of preeclampsia

This version of the guideline includes recommendations on the use of urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (uACR) for diagnosis of proteinuria in pregnancy as well as the clinical use of angiogenic markers.

In summary, we recommend that urine dipstick can be used as an initial screening tool; however, dipstick alone is inadequate to diagnose proteinuria in pregnancy (2B). For quantitative testing, a uPCR of ≥ 30 mg/mmol can be used (1B). Where uPCR is unavailable, a uACR with a cut‐off ≥ 8 mg/mmol can be used (2B).

Where available in a timely manner, the sFlt‐1:PlGF ratio with a cut‐off < 38 can be used in women over 20 weeks’ gestation with clinical suspicion of preeclampsia to rule out preeclampsia within one to four weeks of testing (2D). At the time of publication, the use of an elevated sFlt‐1:PlGF ratio (> 85) in diagnosing preeclampsia, determining fetal outcomes, severity of disease, timing of birth and routine screening in asymptomatic women are not recommended until more data are available (2D).

Similarly, more data on the clinical application of PlGF alone testing in women with clinical suspicion of preeclampsia are required before clinical implementation of testing based on PlGF alone in Australia and New Zealand. At the time of publication, both angiogenic biomarkers (sFlt‐1:PlGF ratio and PlGF alone) are not widely accessible in Australia and New Zealand. The group acknowledges that RCTs on this topic are ongoing and that the recommendations on the clinical application of angiogenic biomarkers are subject to a review based on updated data in the near future.

Part 5: management of chronic or gestational hypertension in pregnancy

Recommendations on five key clinical questions on the management of chronic or gestational hypertension were made based on 120 RCTs (Box 4).

We recommend that women with gestational or chronic hypertension should have blood pressure controlled to a target of ≤ 135/85 mmHg (1C). Where appropriate, home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) with the use of a validated blood pressure device can be utilised in women with stable chronic or gestational hypertension (1B). The use of HBPM, however, should not replace the minimum recommended frequency of antenatal review according to the woman's parity and stage of pregnancy (Box 4). The guideline includes an infographic on HBPM and sample HBPM log.11

Oral agents such as labetalol, methyldopa and/or nifedipine can be used to manage stable hypertension (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, non‐severe hypertension in preeclampsia) (2C). The choice of agent should be individualised based on availability, women's clinical history and through a shared, informed decision‐making process (Box 4 and Box 5).

There remain inadequate data to suggest the need for planned birth before 37+6 weeks’ gestation in women with stable gestational or chronic hypertension and where there are no concerns for fetal wellbeing. The decision on the timing of birth should be individualised based on women's clinical history and through a shared, informed decision‐making process (Box 4) (2D).

Where indicated, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring should be considered to exclude white coat hypertension in women with isolated hypertension in pregnancy (in the absence of an established diagnosis of preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, or gestational hypertension; Box 4) (Practice point).

Part 6: management of preeclampsia

Recommendations in addressing nine key clinical questions on the management of preeclampsia were made based on 99 RCTs (Box 6).

Oral agents labetalol, methyldopa and/or nifedipine can be used in managing stable (non‐severe/non‐acute) hypertension in women with preeclampsia (Box 5 and Box 4) (2C). Short‐acting agents, such as intravenous hydralazine, intravenous labetalol, oral immediate release nifedipine or intravenous diazoxide are recommended in managing acute hypertension (≥ 160/110 mmHg; Box 6 and Box 7) (2C). The use of magnesium sulphate is strongly recommended in women who are at risk of eclampsia (Box 8 and Box 6) (1A).

Timing of birth for women with preeclampsia should be based on the maternal and fetal indications. Birth should be considered at any gestation in the event of significant deterioration. At ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation, birth should be initiated in women with preeclampsia (2D). At < 37 weeks’ gestation, the decision on expectant management or immediate birth should be made based on maternal and fetal stability and balanced against risks arising from preterm birth (Box 6) (2D).

For women at risk of preterm birth, the use of corticosteroid is recommended in women who are at risk of birth < 34 weeks’ gestation (2A). The use of magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection is strongly recommended in women at risk of preterm birth at < 30 weeks’ gestation (Box 6) (2A).

As preeclampsia is a risk factor for venous thromboembolism (VTE), it is important to consider VTE prophylaxis in women with preeclampsia (Practice point). VTE risk assessment should be made based on local hospital or state‐based protocols or policies. In the absence of relevant guidance, this guideline includes a VTE risk assessment tool for use in women with preeclampsia.11

Part 7: immediate and short term postpartum care

It is important to note that there are significant differences in the postpartum care of women with HDP compared with women without. Newer data from 14 RCTs informed these updated recommendations.

The routine use of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in postpartum pain management in women with preeclampsia is conditionally recommended against until more data on safety are available (2C). The short term use of loop diuretics in the in‐patient setting can be considered where clinically indicated (ie, pulmonary oedema, clinical features of fluid overload) (2C).

There remain inadequate data to suggest the superiority of a single agent or group of agents in managing hypertension postpartum. The antihypertensives used antenatally can be continued postpartum, although in addition, enalapril can be used in the postpartum period. The choice of antihypertensive should be made through a shared, informed decision‐making process, particularly in lactating women (2D). The group acknowledges that there are ongoing RCTs examining antihypertensives in the postpartum period and that the recommendation on the choice of antihypertensives is subject to review based on future updated data.

Part 8: long term postpartum care

It is increasingly evident that women who develop preeclampsia and gestational hypertension in pregnancy are at an increased long term risk of ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension and renal disorders. At the time of publication, there remain limited data on appropriate postpartum interventions in reducing the long term metabolic and cardiovascular risks. The recommendations presented in Box 9 are practice points based on data and clinical practice that are current at the time of publication. The guideline includes a clinician checklist and patient infographic that can be used in counselling women on the importance of postpartum and long term follow‐up.11

Importantly, health care providers should assess for normalisation of abnormal clinical and biochemical findings that developed during the pregnancy (eg, proteinuria, liver function abnormalities, hypertension) (Practice point). Where normalisation does not occur by three to six months, further investigation may be required (Practice point). The working group are aware of ongoing RCTs on this topic and anticipates an update in the rating of current recommendations based on new data in the near future.

Conclusion

The SOMANZ hypertension in pregnancy guideline 2023 presents significant updates on evidence‐based recommendations for screening, prevention and management of HDP that has been developed to NHMRC's standards. We encourage users to refer to the main document of the guideline for in‐depth information on the recommendations made and for future updates on recommendations.11

Box 1 – Definitions of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP)

|

Classification |

Description |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Preeclampsia |

Preeclampsia is a multisystem disorder defined as the new onset of hypertension (sBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/ or dBP ≥ 90 mmHg) after 20 weeks’ gestation accompanied by one or more of the following signs of new onset organ involvement:

|

||||||||||||||

|

Gestational hypertension |

Gestational hypertension is defined as the new onset of hypertension after 20 weeks’ gestation without any maternal or fetal features of preeclampsia, followed by normalisation of BP within 3 months postpartum |

||||||||||||||

|

Superimposed preeclampsia |

Superimposed preeclampsia is defined as features of preeclampsia superimposed on either pre‐existing chronic hypertension, or pre‐existing renal disease, or both, after 20 weeks’ gestation |

||||||||||||||

|

Chronic hypertension |

Chronic hypertension is defined as the presence of hypertension (sBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or dBP ≥ 90 mmHg) before pregnancy or before 20 weeks’ gestation |

||||||||||||||

|

White coat hypertension |

White coat hypertension is defined as raised BP (sBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or dBP ≥ 90 mmHg) in the presence of a clinical attendant (clinical BP) with normal BP readings when assessed in a non‐clinical setting (ambulatory or home BP monitoring) |

||||||||||||||

|

Masked hypertension |

Masked hypertension refers to normal BP readings in a clinical setting with raised BP (sBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or dBP ≥ 90 mmHg) in a non‐clinical setting (ambulatory or home BP monitoring) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

BP = blood pressure; dBP = diastolic blood pressure; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; sBP = systolic blood pressure; uPCR = urinary protein to creatinine ratio. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Clinical factors used in identifying women at risk of preeclampsia*

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Factors identified as “high risk” for developing preeclampsia (one or more risk factors):

|

|||||||||||||||

Factors identified as “moderate risk” for developing preeclampsia (two or more risk factors):

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Use of preventive strategies (Box 3) is recommended in women with either one or more major risk factors or two or more moderate risk factors. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Summary of recommended preventive interventions*,†

|

Recommended preventive strategies |

|||||||||||||||

|

Clinical question |

Type of recommendation |

Recommendation |

Rating of recommendation |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

3A.1 Aspirin |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

3A.1.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Initiation of aspirin in women at high risk of developing preeclampsia, prior to 16 weeks’ gestation, is strongly recommended |

1B |

||||||||||||

|

3A.1.2 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

The use of 150 mg/day of aspirin is recommended |

1B |

||||||||||||

|

3A.1.3 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

The use of bedtime aspirin is conditionally recommended |

2C |

||||||||||||

|

3A.1.4 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Cessation of aspirin between 34 weeks’ gestation and birth is conditionally recommended. The exact timing of cessation should be based on individualised clinical judgment and shared, informed decision making with the patient |

2B |

||||||||||||

|

3A.1.5 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Universal aspirin in low risk nulliparous women is conditionally recommended against. Shared, informed decision making with the patient is recommended where appropriate risk stratification is not possible |

2B |

||||||||||||

|

3A.1.6 |

Practice point |

Counselling on the use of aspirin in pregnancy is recommended to improve adherence to aspirin in pregnancy |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

3A.2 Oral supplemental calcium |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

3A.2.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

The use of supplemental calcium is strongly recommended in pregnant women with low dietary calcium intake (< 1 g/day) |

1C |

||||||||||||

|

3A.2.2 |

Practice point |

Assess dietary calcium intake prior to recommending oral calcium supplementation |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

3A.2.3 |

Practice point |

Consider assessing serum corrected calcium prior to commencement of calcium oral supplementation (to ensure the absence of underlying hypercalcaemia) |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

3B.1 Exercise or physical activity |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

3B.1.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Moderate intensity exercise, in the form of aerobic, stretching and/or muscle resistance exercises, for a total of 2.5–5 hours a week, as recommended as part of routine pregnancy wellbeing has the added benefit of reducing the risk of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Adherence to the current recommended exercise regimen for general pregnancy wellbeing is encouraged |

2D |

||||||||||||

|

3B.1.2 |

Practice point |

Exercise regimen should be commenced early in the pregnancy |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

PP = practice point. * Details on preventive strategies currently not recommended can be accessed through the main guideline document.11 † Current as of January 2024. Please refer to https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/ for updates.11 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Summary of recommendations on management of chronic and gestational hypertension*

|

Management of chronic or gestational hypertension in pregnancy |

|||||||||||||||

|

Clinical question |

Type of recommendation |

Recommendation |

Rating of recommendation |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

5.1 BP target in women with chronic or gestational hypertension |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Women with gestational or chronic hypertension should have tight blood pressure control to a target of ≤ 135/85 mmHg |

1C |

||||||||||||

|

5.2 HBPM in monitoring women with stable chronic or gestational hypertension |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

5.2.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Where appropriate, HBPM with the use of a validated blood pressure device can be used in women with chronic or gestational hypertension. The use of HBPM, however, should not replace the minimum recommended frequency of antenatal review according to the woman's parity and stage of pregnancy |

1B |

||||||||||||

|

5.2.2 |

Practice point |

Compliance and technique with HBPM should be reassessed at each review to ensure ongoing suitability |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

5.3 Antihypertensive agents in the management of stable hypertension |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

5.3.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Oral agents labetalol, methyldopa and/or nifedipine can be used in managing stable hypertension in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, non‐severe hypertension in preeclampsia). The choice of agent should be individualised based on access to the agent, women's clinical history, and through a shared, informed decision‐making process |

2C |

||||||||||||

|

5.3.2 |

Practice point |

In addition to the agents above, oral hydralazine can be used in managing stable hypertension in pregnancy |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

5.4 Timing of birth in women with chronic hypertension or gestational hypertension |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

There remain inadequate data to suggest the need for planned birth between 36 and 37+6 weeks’ gestation in women with gestational or chronic hypertension. The decision on the timing of birth should be individualised based on the patient's clinical and obstetric history and through a shared, informed decision‐making process |

2D |

||||||||||||

|

5.5 Use of ABPM in pregnancy |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

5.5.1 |

Practice point |

ABPM should be considered to exclude white coat hypertension in women with isolated hypertension in pregnancy (in the absence of an established diagnosis of preeclampsia, chronic hypertension, or gestational hypertension) |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

5.5.2 |

Practice point |

Where there are poor pregnancy outcomes in current or previous pregnancies that could not be explained by other factors, we suggest ABPM to assess for masked hypertension |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ABPM = ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; BP = blood pressure; HBPM = home blood pressure monitoring; PP = practice point. * Current as of January 2024. Please refer to https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/ for updates.11 |

|||||||||||||||

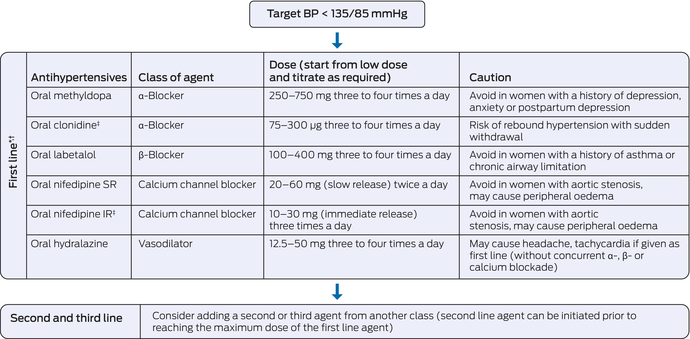

Box 5 – Management of non‐acute/non‐severe hypertension in pregnancy

IR = immediate release; SR = slow release. * Choice of agent should be individualised based on women's medical history and through and informed, shared decision‐making process. † Oxprenolol is no longer accessible in Australia and New Zealand. Where it remains available, a dose of 20–60 mg three times a day can be used. Oxprenolol should be avoided in women with a history of asthma or chronic airway limitation. ‡ Access and supply may be limited in certain parts of Australia and New Zealand.

Box 6 – Summary of recommendations on management of preeclampsia

|

Management of preeclampsia |

|||||||||||||||

|

Clinical question |

Type of recommendation |

Recommendation |

Rating of recommendation |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

6.1 Antihypertensives in the management of stable hypertension in preeclampsia |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Oral agents labetalol, methyldopa and/or nifedipine can be used in managing stable hypertension in pregnancy (gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, non‐severe hypertension in preeclampsia). The choice of agent should be individualised based on access to agent, women's clinical history and through a shared, informed decision‐making process |

2C |

||||||||||||

|

6.2 Management of acute hypertension (≥ 160/110 mm Hg) in preeclampsia |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

6.2.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Short‐acting agents such as IV hydralazine, IV labetalol, oral IR nifedipine or IV diazoxide should be used in managing acute hypertension. The choice of short‐acting antihypertensive should be based on the unit's access and familiarity with agent of choice |

2C |

||||||||||||

|

6.2.2 |

Practice point |

Acute (severe) hypertension should be treated to a target of < 160/110 mmHg |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.3 Timing of birth in preeclampsia |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

6.3.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Birth plan should be initiated women with preeclampsia at ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation |

2D |

||||||||||||

|

6.3.2 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Decision for expectant management or immediate birth in women with preeclampsia < 37 weeks’ gestation should be made based on maternal and fetal clinical stability in weighing the risk of preterm birth. The decision should be made through a shared, informed decision‐making process with the patient |

2D |

||||||||||||

|

6.3.3 |

Practice point |

Birth should be considered at any gestation in the event of deterioration |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.3.4 |

Practice point |

Women with preeclampsia at risk of early preterm birth (< 34 weeks’ gestation) should be considered for a transfer to a unit with appropriate level of neonatal and paediatric care |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.3.5 |

Evidence‐based recommendation and practice point |

There are limited data to support the use of angiogenic biomarkers in determining timing and indication of birth |

2B |

||||||||||||

|

6.3.6 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Where appropriate, consider the use of corticosteroid and magnesium sulphate in women at risk of early preterm birth |

2A |

||||||||||||

|

6.4 Corticosteroid in women with preeclampsia at risk of preterm birth |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

6.4.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Use of corticosteroid (either betamethasone or dexamethasone) is recommended in women with preeclampsia who are at risk of birth at < 34 weeks’ gestation |

2A |

||||||||||||

|

6.4.2 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

There are insufficient data to recommend routine use of corticosteroid in women with preeclampsia who are at risk of birth between 34 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The use of corticosteroid in this setting should be individualised based on clinical assessment and through a shared, informed decision‐making process with the patient |

2B |

||||||||||||

|

6.4.3 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Redosing of corticosteroid can be considered in women with preeclampsia who remain at risk of birth at < 34 weeks’ gestation 7–14 days following initial single dose of corticosteroid. The decision on redosing should be made through a shared, informed decision‐making process with the patient |

2A |

||||||||||||

|

6.5 Magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection in women at risk of preterm birth |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

6.5.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

The use of magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection in women with preeclampsia at risk of preterm birth at < 30 weeks’ gestation is strongly recommended |

2A |

||||||||||||

|

6.5.2 |

Practice point |

Decision on the use of magnesium sulphate for fetal neuroprotection in women with preeclampsia at risk of birth between 30 and 34 weeks’ gestation should be individualised based on clinical assessment and through a shared, informed decision‐making process with the patient |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.6 Magnesium sulphate in minimising the risk of eclampsia and treating eclampsia |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

6.6.1 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Prophylactic magnesium sulphate with an IV loading dose of 4 g followed by maintenance at 1 g/h for 24 h in total or from time of last seizure is strongly recommended in women at risk of eclampsia or recurrent eclampsia |

1A |

||||||||||||

|

6.6.2 |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

There is inadequate evidence to support an alternative magnesium regimen or the use of anticonvulsants for the prevention of eclampsia |

2C,2D |

||||||||||||

|

6.7 Corticosteroid in the management of HELLP syndrome |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

The use of corticosteroid in managing HELLP syndrome is not recommended until more data are available |

2C |

||||||||||||

|

6.8 Thromboprophylaxis in women with preeclampsia |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

6.8.1 |

Practice point |

Women's risk of VTE and need for VTE prophylaxis should be made based on the current local hospital or state‐based protocol or policy. In the absence of which, the included VTE risk in pregnancy assessment tool can be used |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.8.2 |

Practice point |

Risk assessment should be conducted in early pregnancy (first trimester) or pre‐conception, at every admission into hospital, at the time of diagnosis of preeclampsia or new intercurrent medical issue and in the immediate postpartum period |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.8.3 |

Practice point |

Concurrent use of LMWH for VTE prevention and aspirin for preeclampsia prevention should be done in weighing the benefits and risks to the maternal and fetal outcomes and should be done through a shared, informed decision‐making process with the patient |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

6.9 Plasma expansion in women with preeclampsia |

Evidence‐based recommendation |

Routine plasma expansion for management of preeclampsia is not recommended until more data are available |

2C |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IR = immediate release; IV = intravenous; HELLP = haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count; LMWH = low molecular weight heparin; PP = practice point; VTE = venous thromboembolism. * Current as of January 2024. Please refer to https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/ for updates.11 |

|||||||||||||||

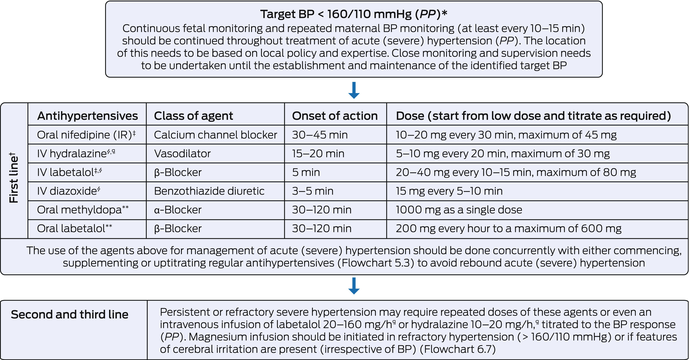

Box 7 – Management of acute hypertension in pregnancy

BP = blood pressure; IV = intravenous; PP = practice point. * Target BP should be individualised particularly in the presence of features of fetal compromise. † The most important consideration in choice of antihypertensive agent is that the unit has access and familiarity with that agent. Agents should be uptitrated as indicated in the first line section in this Box, and if target BP is not reached, second and third line treatment options should be employed. ‡ Supply and access may be limited in Australia and New Zealand. § Administration of IV agents should be followed by a 10–20 mL normal saline IV flush to ensure systemic circulation of the administered agent. ¶ 250 mL IV fluid preloading (normal saline 0.9%) should be considered to minimise the risk of hypotension (PP). ** Slower onset of action (up to two hours). Use can be individualised based on clinical setting (ie, in the absence of short‐acting agents).

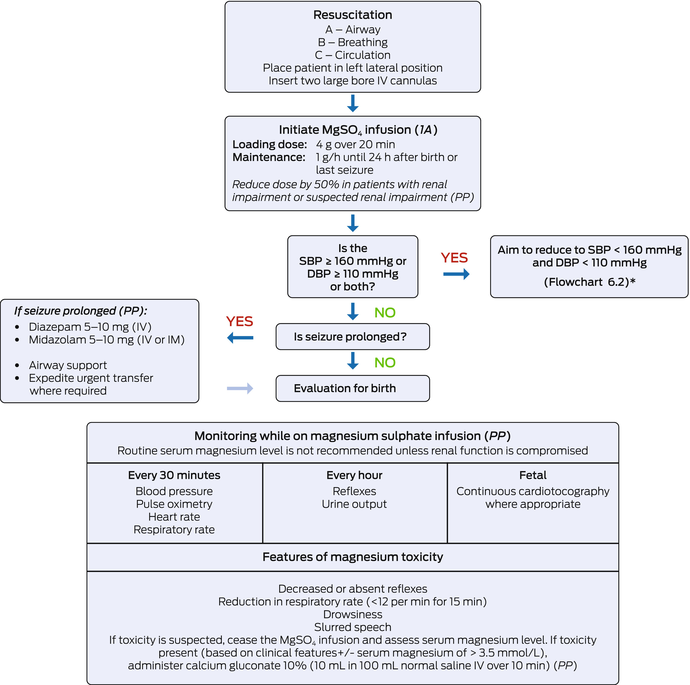

Box 8 – Management of eclampsia

1A = based on 1A quality evidence; IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous; MgSO4 = magnesium sulphate; PP = practice point. * This flow chart provides guidance based on the evidence at the time of which this guideline was developed. Management of eclampsia must be done in accordance with local protocol where applicable.11

Box 9 – Summary of recommendations on the long term postpartum care of women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

|

Long term postpartum care |

|||||||||||||||

|

Clinical question |

Type of recommendation |

Recommendation |

Rating of recommendation |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

8.1.1 |

Practice point |

Women should be informed of the long term risks associated with preeclampsia and the importance of postpartum follow‐up prior to discharge from hospital |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

8.1.2 |

Practice point |

Women should be reviewed by a health care provider within one week of discharge from hospital to ensure stable blood pressure after discharge |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

8.1.3 |

Practice point |

At 3–6 months postpartum, a follow‐up review of blood pressure (consider a 24‐hour blood pressure monitor if not previously done), urinary protein assessment (uACR and/or uPCR), BMI and metabolic profile (fasting blood glucose and fasting cholesterol assessment) should be considered. Interventions for any abnormalities (ie, further investigations, specialist referral, weight management, lifestyle changes, smoking cessation) should be discussed |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

8.1.4 |

Practice point |

A yearly follow‐up of blood pressure, urinary protein assessment, BMI and metabolic profile should be considered in identifying early abnormalities in the first 5–10 years postpartum |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

8.1.5 |

Practice point |

At every review, women should be opportunistically screened for postpartum depression and anxiety. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) can be used as an initial screening tool |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

8.1.6 |

Practice point |

At every review, women should be counselled on the risk of preeclampsia in subsequent pregnancies and the importance of pre‐conception medical optimisation, contraception (where indicated) and risk minimisation strategies (ie, prophylactic aspirin) |

PP |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

BMI = body mass index; uACR = urinary albumin to creatinine ratio; uPCR = urinary protein to creatinine ratio. * Current as of Jan 2024. Please refer to https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/ for updates.11 |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Renuka Shanmugalingam1,2

- Helen L Barrett3,4

- Amanda Beech3,4

- Lucy Bowyer3

- Tim Crozier5,6

- Amanda Davidson7

- Marloes Dekker Nitert8

- Kerrie Doyle2

- Luke Grzeskowiak9

- Nicole Hall1

- Hicham Ibrahim Cheikh Hassan10,11

- Annemarie Hennessy2,12

- Amanda Henry4,13

- David Langsford14,15

- Vincent WS Lee16,17

- Zachary Munn18

- Michael J Peek19,20

- Joanne M Said15,21

- Helen Tanner22

- Rachel Taylor23

- Meredith Ward3

- Jason Waugh24

- Linda LY Yen25

- Ellie Medcalf16

- Katy JL Bell16

- Deonna Ackermann16

- Robin Turner26

- Angela Makris1,2

- 1 Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney, NSW

- 4 University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

- 5 Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, VIC

- 6 Monash University, Melbourne, VIC

- 7 Australian Pregnancy Hypertension Foundation Limited, Sydney, NSW

- 8 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 9 Flinders Medical Centre, Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

- 10 Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health District, Wollongong, NSW

- 11 University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW

- 12 Campbelltown Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 13 St George Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 14 Grampians Health, Ballarat, VIC

- 15 University of Melbourne, Ballarat, VIC

- 16 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 17 Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 18 Health Evidence Synthesis, Recommendations and Impact (HESRI), University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA

- 19 Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

- 20 Centenary Hospital for Women and Children, Canberra, ACT

- 21 Joan Kirner Women's and Children's Sunshine Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 22 Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, Brisbane, QLD

- 23 Waikato Women's Hospital, Hamilton, New Zealand

- 24 University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

- 25 Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand Counties Manukau, Auckland, New Zealand

- 26 Biostatistics Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Western Sydney University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Western Sydney University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This guideline was funded by the Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) membership. The working group members are mostly volunteers who provided their valuable time and expertise at no cost. SOMANZ acknowledges the significant contribution from all working group members, Michael Ritchie (graphic designer), and National Health and Medical Research Council's Clinical Practice Guidelines Team in the development of this guideline. A detailed list of the working group members is available in the main guideline document (https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/).

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, et al. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013; 170: 1‐7.

- 2. Wallis AB, Saftlas AF, Hsia J, Atrash HK. Secular trends in the rates of preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension, United States, 1987–2004. Am J Hypertens 2008; 21: 521‐526.

- 3. Wang W, Xie X, Yuan T, et al. Epidemiological trends of maternal hypertensive disorders of pregnancy at the global, regional, and national levels: a population‐based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021; 21: 364.

- 4. Thornton C, Dahlen H, Korda A, Hennessy A. The incidence of preeclampsia and eclampsia and associated maternal mortality in Australia from population‐linked datasets: 2000–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013; 208: 476 e1‐e5.

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Maternal deaths in Australia 2008–2012 [Cat. No. PER 70]. Canberra: AIHW, 2015. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers‐babies/maternal‐deaths‐in‐australia‐2008‐2012/summary (viewed Jan 2024).

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's mothers and babies [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/mothers‐babies/australias‐mothers‐babies/contents/summary (viewed Jan 2024).

- 7. Anderson NH, Sadler LC, Stewart AW, et al. Ethnicity, body mass index and risk of pre‐eclampsia in a multiethnic New Zealand population. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2012; 52: 552‐558.

- 8. Korzeniewski SJ, Sutton E, Escudero C, Roberts JM. The Global Pregnancy Collaboration (CoLab) symposium on short‐ and long‐term outcomes in offspring whose mothers had preeclampsia: a scoping review of clinical evidence. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022; 9: 984291.

- 9. Lowe SA, Bowyer L, Lust K, et al. SOMANZ guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2015; 55: e1‐e29.

- 10. National Health and Medical Research Council. 2016 NHMRC standards for guidelines [website]. Canberra: NHMRC, 2016. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelinesforguidelines/standards (viewed Jan 2024).

- 11. Society of Obstetric Medicine Australia and New Zealand. Hypertension in pregnancy guideline 2023. Sydney: SOMANZ, 2023. https://www.somanz.org/hypertension‐in‐pregnancy‐guideline‐2023/ (viewed Jan 2024).

- 12. Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction — GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64: 383‐394.

- 13. Alonso‐Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016; 353: i2089.

Abstract

Introduction: Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) affect up to 10% of all pregnancies annually and are associated with an increased risk of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. This guideline represents an update of theSociety of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ) guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014 and has been approved by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) under section 14A of the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992 . In approving the guideline recommendations, NHMRC considers that the guideline meets NHMRC's standard for clinical practice guidelines.

Main recommendations: A total of 39 recommendations on screening, preventing, diagnosing and managing HDP, especially preeclampsia, are presented in this guideline. Recommendations are presented as either evidence‐based recommendations or practice points. Evidence‐based recommendations are presented with the strength of recommendation and quality of evidence. Practice points were generated where there was inadequate evidence to develop specific recommendations and are based on the expertise of the working group.

Changes in management resulting from the guideline: This version of the SOMANZ guideline was developed in an academically robust and rigorous manner and includes recommendations on the use of combined first trimester screening to identify women at risk of developing preeclampsia, 14 pharmacological and two non‐pharmacological preventive interventions, clinical use of angiogenic biomarkers and the long term care of women who experience HDP. The guideline also includes six multilingual patient infographics which can be accessed through the main website of the guideline. All measures were taken to ensure that this guideline is applicable and relevant to clinicians and multicultural women in regional and metropolitan settings in Australia and New Zealand.