The known: Vaccination of pregnant women against pertussis is highly effective in preventing infection of their infants during their first seven months of life.

The new: The proportion of pregnant women in northern and western Australia vaccinated against pertussis was smaller for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (37%) than other women (52%), and the impact of maternal vaccination on pertussis incidence was not statistically significant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants.

The implications: Rates of pertussis vaccination during pregnancy and pertussis infections in infants since the COVID‐19 pandemic (when the number of notified cases declined) should be assessed. Increasing the number of vaccinated pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women could reduce the rate of infections among their infants.

The global burden of pertussis is greatest for infants under four months of age.1 Rates of severe illness (including disease requiring hospitalisation or intensive care) and death are highest for this age group because routine vaccination schedules mean that infants are not fully vaccinated until six months of age. In Australia, vaccination against pertussis is undertaken at two, four, and six months of age.2 The greatest sources of infection risk for infants are family members, particularly parents and siblings, and child care facilities.3,4

Vaccinating pregnant women against pertussis provides passive protection to infants via maternal antibody transfer. This protection, estimated to prevent 60%5 to 91%6 of potential infant pertussis infections, is thought to persist until infants can be protected by childhood vaccination. For this reason, pertussis vaccination programs for pregnant women commenced in August 2014 in Queensland and during April–June 2015 in other Australian states and territories.7 However, no vaccination uptake target has been set. About 27% of eligible Queensland, Western Australia, and Northern Territory women were vaccinated in 2014–15 (161 620 of 591 868)8 before steadily increasing during 2016–21 to more than 70% in most states and territories.9

During 1997–2014 (ie, prior to the introduction of maternal pertussis vaccination programs), rates of notified pertussis infection, hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission, and death were three to eight times as high for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants and children under five years of age as for non‐Indigenous infants and children.10,11 Australian studies of the effectiveness of maternal vaccination for preventing pertussis infections in their infants12,13 have not taken Indigenous status into account, were not large enough to provide robust estimates for Indigenous infants, and did not undertake time‐varying statistical analyses.

The primary aim of our retrospective cohort study was therefore to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination for preventing laboratory‐confirmed pertussis infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants under seven months of age in the Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia.

Methods

For our retrospective cohort study, health department data linkage branches probabilistically linked Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australian administrative health data for a previously established mother–infant cohort (Links2HealthierBubs).14 The cohort included all pregnant women who gave birth to infants during 1 January 2012 – 31 December 2017 at a gestational age of at least 20 weeks or with a birthweight of at least 400 g. The linked datasets were:

- perinatal data collections: NT Perinatal Trends, the Queensland Perinatal Data Collection, and the WA Midwives Notification System;

- vaccination registers and databases: the NT Immunisation Register (NTIR), the Queensland Vaccination Information and Vaccination Administration System (VIVAS), and the WA Antenatal Vaccination (WAAVD) database; and

- infectious diseases databases: the NT Communicable Infectious Diseases, Queensland Notifications and Other Communicable Infectious Diseases (NOCS), and WA Notifiable Infectious Diseases databases.

Indigenous status

For WA, the Data Services Branch used a validated algorithm across multiple datasets to identify the Indigenous status of the mothers, an approach that achieves data accuracy and completeness of greater than 99%.15 For the NT and Queensland, multiple variables for Indigenous status in each health administrative dataset were used.

Maternal pertussis vaccinations

We calculated maternal pertussis vaccination rates during 1 August 2014 – 31 December 2017 from vaccination register and perinatal data collection data; this period included the introduction of maternal pertussis vaccination programs in Queensland (August 2014) and NT and WA (April 2015).7 We compare vaccination rates, overall and by selected socio‐demographic and health characteristics, for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous women in dumbbell plots. We also compared the overall vaccination rates for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous pregnant women in a multivariable logistic regression analysis adjusted for maternal age, residential postcode‐based remoteness (Australian Statistical Geography Standard structure16) and socio‐economic status (Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA] Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage [IRSAD]17), initiation of antenatal care, mother's health conditions, and year of birth; we report adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Pertussis infections in infants

We calculated the incidence of pertussis infections per 10 000 births among infants under seven months of age born during 1 January 2012 – 31 December 2017, separately for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous infants, from notifiable infectious diseases and births data.

Effectiveness of maternal vaccination for protecting infants from pertussis infection

We compared pertussis infection rates for infants whose mothers were or were not vaccinated during pregnancy in separate mixed effects models for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous infants (infant age in months as the time variable). We restricted this analysis to data for women who gave birth to live singleton babies and for whom complete information regarding maternal age, pre‐existing health conditions, parity, smoking status, trimester at initiation of antenatal care, socio‐economic status, influenza vaccination status, and year and season of conception were available. We also excluded women who had been vaccinated against pertussis less than 14 days prior to giving birth. Our models included two random intercepts: one for state or territory to account for clustering within jurisdictions, and one for mothers to account for clustering within siblings.

To reduce confounding, models were weighted by inverse probability of treatment weights derived from multivariable logistic regression models of the probability of pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as one minus the weighted hazard ratio. All analyses were conducted in Stata 17.1.

Ethics approval

The human research ethics committees of the WA Department of Health (HREC 2016/56), Curtin University (HRE2017‐0808), the Menzies School of Health Research (HREC 2018‐3199), the Queensland Health and Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital (HREC/2018/QRBW/47660), and WA Aboriginal Health (HREC 889) approved the study.

Results

A total of 603 708 mother–infant pairs with birth dates during 1 January 2012 – 31 December 2017 were identified (NT, 23 387; Queensland, 370 945; WA, 209 376); 279 418 infants born during 1 August 2014 – 31 December 2017 were included in the vaccination effectiveness analysis (NT, 9996; Queensland, 194 373; WA, 75 049), including 19 892 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and 259 526 non‐Indigenous infants. The completeness of Indigenous status data exceeded 99% for all three jurisdictions.

Maternal pertussis vaccinations

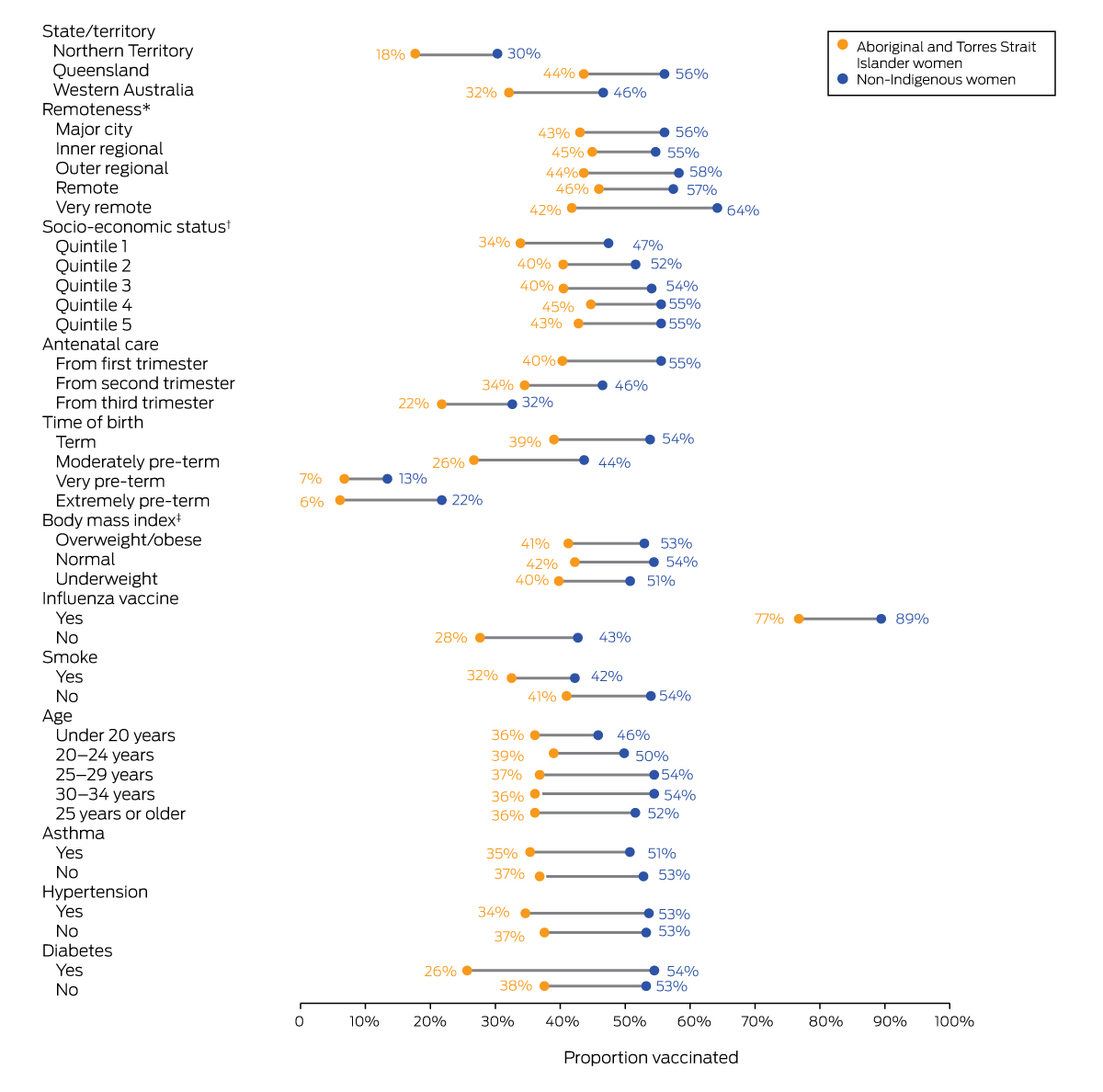

Of the 279 418 mothers who gave birth to live infants during 2012–2017, 144 429 had received pertussis vaccine doses during pregnancy (51.7%). The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who had been vaccinated (7398 of 19 892, 37.2%) was smaller than that of non‐Indigenous women (137 034 of 259 526, 52.8%; aOR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.62–0.70). The largest differences in vaccination rates between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous women were for those with diabetes (137 of 536 [25.6%] v 1011 of 1861 [54.3%]), women living in very remote areas (506 of 1215 [41.6%] v 719 of 1120 [64.2%]), women with hypertension (140 of 407 [34.4%] v 1878 of 3520 [53.4%]), women aged 30–34 years (1180 of 3242 [36.4%] v 48 854 of 89 881 [54.4%]), and women who gave birth moderately pre‐term (492 of 1858 [26.5%] v 6278 of 14 409 [43.6%]) (Box 1).

Infant pertussis infections

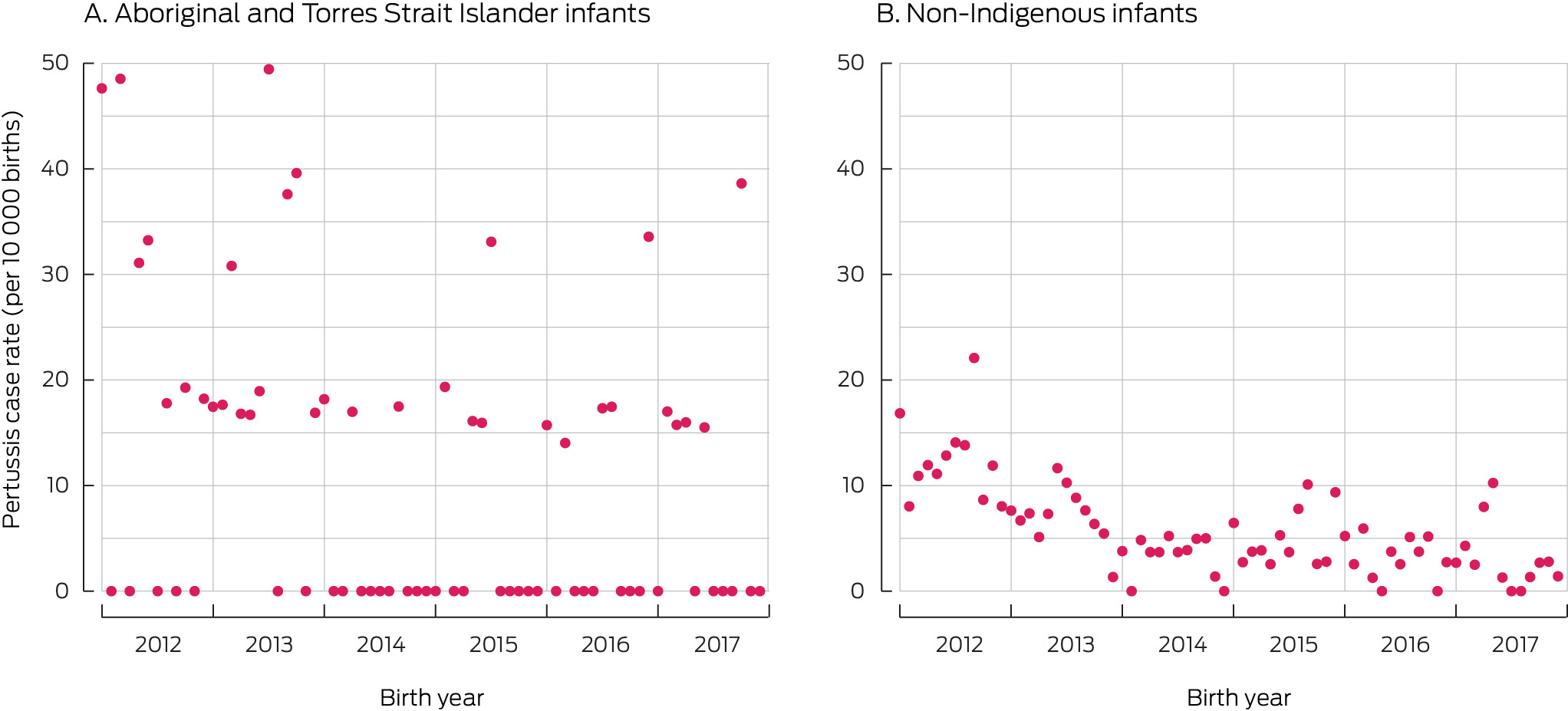

The overall incidence of pertussis infection was 19.2 (95% CI, 11.8–31.1) cases per 10 000 births in January 2012 and 1.3 (95% CI, 0.2–7.4) cases per 10 000 births in December 2017. The annual rate for non‐Indigenous infants declined from 16.8 (95% CI, 9.9–29) in 2012 to 1.4 (95% CI, 0.3–8.0) cases per 10 000 births in 2017; for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants, it declined from 47.6 (95% CI, 16.2–139) to 38.6 (95% CI, 10.6–140) cases per 10 000 births. The incidence of pertussis infection during the fourth quarter of 2017 among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants (12.5 cases per 10 000 births; 95% CI, 3.4–45) was similar to that for non‐Indigenous infants during the first quarter of 2012, before maternal pertussis vaccination programs were introduced (11.9 [95% CI, 8.3–17.3] cases per 10 000 births) (Box 2).

The highest rates of infant pertussis infection were for those born to women with hypertension (15.3 [95% CI, 7.0–33.3] cases per 10 000 infants), women under 20 years of age (14.6 [95% CI, 8.7–24.5] cases per 10 000 infants), and women who smoked (12.2 [95% CI, 8.9–16.7] cases per 10 000 infants) (Supporting Information).

Effectiveness of maternal vaccination for protecting infants from pertussis infection

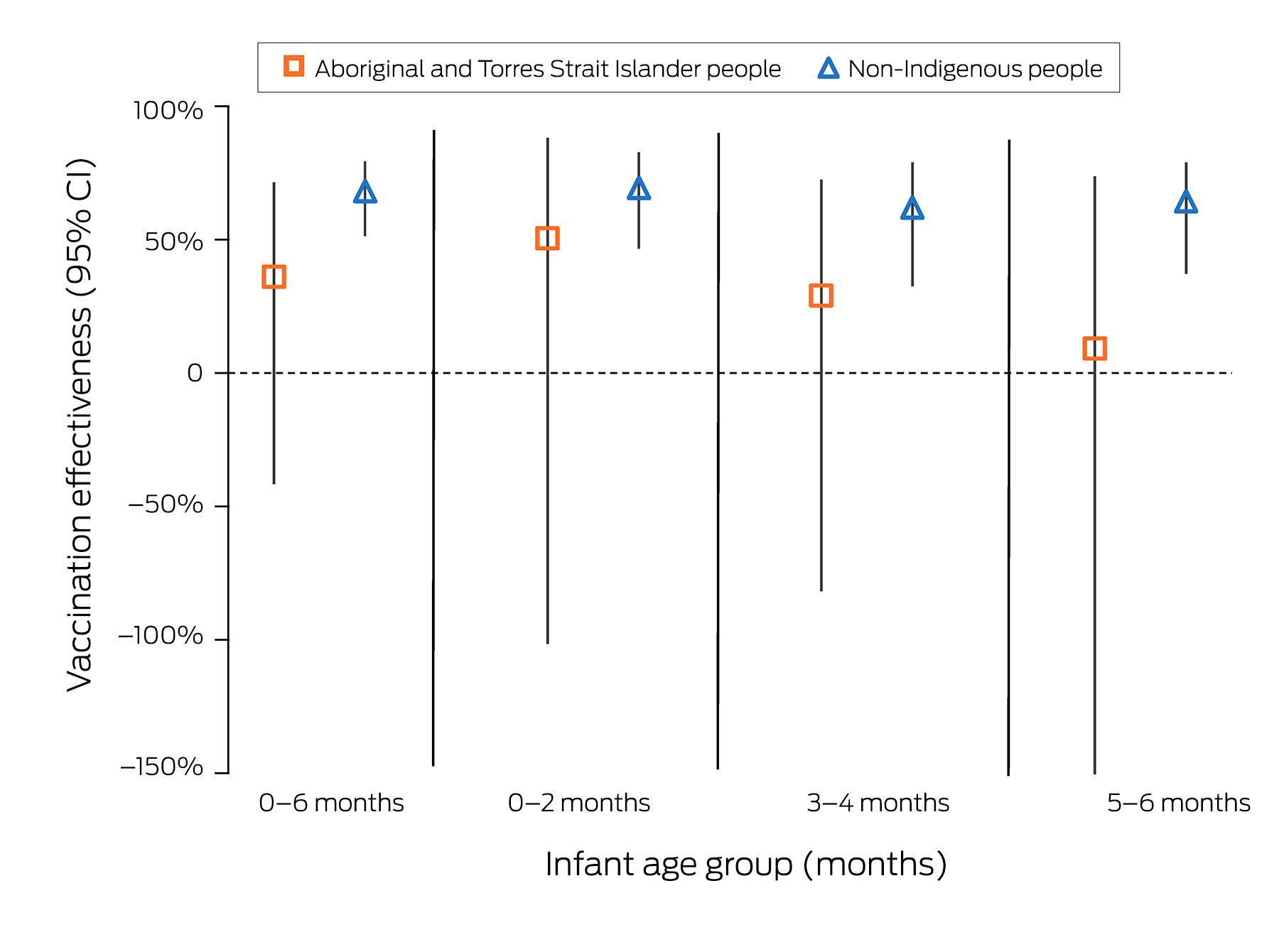

For non‐Indigenous infants under seven months of age, the estimated effectiveness of maternal vaccination during 2014–17 was 68.2% (95% CI, 51.8–79.0%); for infants to two months of age it was 69.5% (95% CI, 47.1–82.4%); for infants aged 3–4 months, 62.1% (95% CI, 33.0–78.6%); and for infants aged 5–6 months, 64.4% (95% CI, 37.6–78.6%). For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants, the estimated effectiveness of maternal vaccination was not statistically significant at any age: for all infants under seven months of age it was 36.1% (95% CI, –41.3% to 71.1%). For infants to two months of age it was 50.5% (95% CI, –101% to 87.8%); for infants aged 3–4 months, 28.9% (95% CI, –81.4% to 72.2%); and for infants aged 5–6 months, 9.2% (95% CI, –210% to 73.3%) (Box 3).

Discussion

Our study is the largest to estimate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination for preventing pertussis infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants under seven months of age. Although pertussis vaccination is recommended and fee‐free for every pregnant woman in Australia, only 37.2% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women had been vaccinated during pregnancy. Further, we have previously reported that vaccination rates were lower for Indigenous than non‐Indigenous pregnant women during 2015–2017 in the NT (17% v 29%), Queensland (50% v 64%), and WA (30% v 42%).18 This finding is consistent with the lower uptake of pertussis vaccination during pregnancy by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women reported for other states; for instance, the difference was as large as 20 percentage points in Victoria and South Australia.9

We have previously reported that geographic, social, and financial factors influence the uptake of pertussis vaccination by pregnant women.18 Uptake was lower among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in remote regions of the NT, Queensland, and WA (v other geographic remoteness classifications: prevalence ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.69–0.75), and was higher among Indigenous women in areas of higher socio‐economic status (prevalence ratio, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.17–1.48).18 These factors need to be considered when attempting to improve maternal pertussis vaccination rates. We have also reported that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, women under 20 years of age, women who smoke during pregnancy, and women who have previously given birth are all less likely to be vaccinated during pregnancy, whereas antenatal care during the first trimester and influenza vaccination during pregnancy are associated with pertussis vaccination during pregnancy.8

We did not find evidence for a population‐level impact of maternal vaccination on pertussis incidence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants under seven months of age, nor for the effectiveness of maternal vaccination for preventing infections in infants. The incidence of pertussis infections was, in fact, higher among Indigenous infants several years into the maternal pertussis vaccination programs than among non‐Indigenous infants prior to their implementation. Vaccine effectiveness estimates would be more robust were vaccination uptake among pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women increased. In a small New South Wales case–control study (234 infants; Indigenous status not reported) the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination for preventing infection in infants under six months of age was not statistically significant (39%; 95% CI, –12% to 66%), but the estimated effectiveness for preventing severe disease (ie, leading to hospitalisation) was 94% (95% CI, 59–99%),13 consistent with the findings of a 2020 systematic review of overseas studies (91–94% for prevention of hospitalisation).19 The vaccination effectiveness estimates of a Victorian study for 2015–201720 were similar to those of our study and of the NSW study with respect to non‐Indigenous infants, but the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers (2575 women) was smaller than in our study. The authors acknowledged that low infant pertussis infection numbers constrained the statistical power of their analysis;20 further, they reported risk ratios rather than hazard ratios, the preferred statistic for analyses of serial data points.

The combination of maternal pertussis vaccination and timely infant vaccination (ie, according to the two‐, four‐, and six‐month schedule) is crucial for reducing pertussis infections in infants under seven months of age. A Queensland project supported by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners increased the uptake of maternal vaccination against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) during the recent pandemic by providing care closer to or on country,21 a strategy that could be used to improve the uptake of maternal vaccination against pertussis and other diseases during pregnancy.

Limitations

Our study is the largest to have examined the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination for preventing infant infections in Australia, and the only study to provide estimates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants. Our sample size was large, including Indigenous people from multiple states, and the completeness (greater than 99%) of Indigenous status data strengthened the internal validity of our study and minimised potential selection bias.

However, the low number of notified pertussis infections during 2015–2017 affected the precision of our estimates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants, as indicated by the broad confidence intervals. Our study period preceded the COVID‐19 pandemic, and the pertussis notification rate was higher than during 2020–2022. Our study could be extended to assess the current disease burden and the impact of maternal vaccination. Whether our findings can be generalised from the three included states and territories to other Australian jurisdictions is uncertain.

Our observational study design entailed risks of bias with respect to exposure and outcome variables and of confounding. To minimise these risks, we adjusted our analyses for a number of possible confounders. Data for vaccination status and notified infections were extracted from registers and databases; the possibility of misclassification of exposure and outcomes cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

To reduce the burden of pertussis infections among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants, optimising the vaccination of pregnant women against pertussis is crucial. The pertussis disease burden in Australia should be re‐examined to establish whether the current level more closely matches the pre‐pandemic level or the lower burden during the pandemic. In the meantime, increasing the vaccination of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women during pregnancy will require culturally appropriate, innovative strategies co‐designed in partnership with Indigenous organisations and communities and supported by all tiers of government.

Box 1 – Pertussis vaccination rates for pregnant women in the Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia, 2015–2017, by Indigenous status

* Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness Structure, by residential postcode.16† Index of Relative Socio‐economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD), by residential postcode.17‡ Overweight/obese, > 25 kg/m2); normal, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, underweight, < 18.5 kg/m2.

Box 2 – Pertussis infections in infants under seven months of age in the Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia, 2012–2017, by Indigenous status

Box 3 – Estimated effectiveness of maternal vaccination for protecting infants from pertussis infection, the Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia, 2015–2017, by Indigenous status*

CI = confidence interval.* Overall, seven of 7395 vaccinated and eighteen of 12 497 unvaccinated Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants, and 26 of 137 034 vaccinated and 73 of 122 492 unvaccinated non‐Indigenous infants had pertussis.

Received 25 May 2023, accepted 10 September 2023

- Lisa McHugh1

- Heather A D’Antoine2

- Mohinder Sarna3,4

- Michael J Binks5,6

- Hannah C Moore6

- Ross M Andrews7

- Gavin F Pereira3,8

- Christopher C Blyth4,9

- Paul Van Buynder10

- Karin Lust11

- Annette K Regan3,12

- 1 The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 2 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research Network, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 3 Curtin University, Perth, WA

- 4 Wesfarmers Centre for Vaccines and Infectious Diseases, Telethon Kids Institute, Perth, WA

- 5 Menzies School of Health Research, Darwin, NT

- 6 Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 7 Office of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health, Brisbane, QLD

- 8 Centre for Fertility and Health, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway

- 9 The University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 10 Griffith University, Gold Coast, QLD

- 11 Royal Brisbane and Woman's Hospital Health Service District, Brisbane, QLD

- 12 University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States of America

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley – The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This investigation was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Project Grant (GNT1141510) and operational funds provided by the Western Australia Department of Health. Lisa McHugh is supported by an NHMRC EL1 Investigator Grant (GNT2016407) at the University of Queensland. Annette K Regan was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (GNT1138425). Hannah C Moore was supported by a Stan Perron Charitable Foundation People Fellowship. Christopher C Blyth was supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (GNT1111596) and NHMRC Investigator award (APP1173163). Michael J Binks was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (GNT1088733) and an NHMRC‐funded Hot North (Improving Health Outcomes in the Tropical North) Fellowship (1131932). Gavin F Pereira was supported by NHMRC Project (GNT1099655) and Investigator Grants (GNT1173991), and by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme (GNT262700). The funding sources had no role in the planning, study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation, reporting or publication.

We thank the Linkages Services Branch of Queensland Health and the data custodians of the Perinatal, Notifications and Other Communicable Infectious Diseases, and Immunisation Data collections; the Linkage and Client Services Teams at the Data Linkage Branch of the Western Australia Department of Health and the data custodians of the Midwives Notification System, the WA Antenatal Vaccination Database, and the WA Notifiable Infectious Diseases Database; and SA‐NT DataLink and the NT Centre for Disease Control, and the data custodians of the NT Perinatal Trends, Communicable Infectious Diseases, and Immunisation Databases.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Yeung KHT, Duclos P, Nelson EAS, Hutubessy RCW. An update of the global burden of pertussis in children younger than 5 years: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 974‐980.

- 2. Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. National Immunisation Program Schedule. Updated 12 July 2023. https://beta.health.gov.au/health‐topics/immunisation/immunisation‐throughout‐life/national‐immunisation‐program‐schedule (viewed Nov 2023).

- 3. Wiley KE, Zuo Y, Macartney KK, McIntyre PB. Sources of pertussis infection in young infants: a review of key evidence informing targeting of the cocoon strategy. Vaccine 2013; 31: 618‐625.

- 4. Bertilone C, Wallace T, Selvey LA. Finding the “who” in whooping cough: vaccinated siblings are important pertussis sources in infants 6 months of age and under. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2014; 38: E195‐E200.

- 5. Regan AK, Moore HC, Binks MJ, et al. Maternal pertussis vaccination, infant immunization, and risk of pertussis. Pediatrics 2023; 152: e2023062664.

- 6. Amirthalingam G, Andrews N, Campbell H, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in England: an observational study. Lancet 2014; 384: 1521‐1528.

- 7. Beard FH. Pertussis immunisation in pregnancy: a summary of funded Australian state and territory programs. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 2015; 39: E329‐E336.

- 8. McHugh L, Van Buynder P, Sarna M, et al. Timing and temporal trends of influenza and pertussis vaccinations during pregnancy in three Australian jurisdictions: the Links2HealthierBubs population‐based linked cohort study, 2012–17. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2023; 63: 27‐33.

- 9. McRae JE, McHugh L, King C, et al. Influenza and pertussis vaccine coverage in pregnancy in Australia, 2016–2021. Med J Aust 2023; 218: 528‐541. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/11/influenza‐and‐pertussis‐vaccine‐coverage‐pregnancy‐australia‐2016‐2021

- 10. McHugh L, Viney KA, Andrews RM, Lambert SB. Pertussis epidemiology prior to the introduction of a maternal vaccination program, Queensland Australia. Epidemiol Infect 2017; 146: 207‐217.

- 11. Joseph T, Menzies R, Sinclair M. Vaccination for our mob, 2006–2010. Summary report of Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination coverage in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Australia, 2006 to 2010. Sydney: National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases, 2014; pp. 27‐29. https://nacchocommunique.com/wp‐content/uploads/2017/04/vaccination‐for‐our‐mob‐2006‐2010.pdf (viewed Dec 2023).

- 12. Quinn HE, Comeau JL, Marshall HS, et al. Pertussis disease and antenatal vaccine effectiveness in Australian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2021; 41: 180‐185.

- 13. Saul N, Wang K, Bag S, et al. Effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination in preventing infection and disease in infants: the NSW public health network case–control study. Vaccine 2018; 36: 1887‐1892.

- 14. Sarna M, Andrews RM, Moore H, et al. “Links2HealthierBubs” cohort study: protocol for a record linkage study on the safety, uptake and effectiveness of influenza and pertussis vaccines among pregnant Australian women. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e030277.

- 15. Christensen D, Davis G, Draper G, et al. Evidence for the use of an algorithm in resolving inconsistent and missing Indigenous status in administrative data collections. Aust J Soc Issues 2014; 49: 423‐443.

- 16. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS): Volume 5. Remoteness structure, July 2016 (1270.0.55.005). 16 Mar 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1270.0.55.005 (viewed Dec 2023).

- 17. Australian Bureau of Statistics. IRSAD. In: Census of Population and Housing: Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016 (2033.0.55.001). 27 Mar 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people‐and‐communities/socio‐economic‐indexes‐areas‐seifa‐australia/latest‐release#index‐of‐relative‐socio‐economic‐advantage‐and‐disadvantage‐irsad‐ (viewed Dec 2023).

- 18. McHugh L, Regan AK, Sarna M, et al. Inequity of antenatal influenza and pertussis vaccine coverage in Australia: the Links2HealthierBubs record linkage cohort study, 2012–2017. [Cited here: supplementary figure 1 and table 2]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023; 23: 314.

- 19. Vygen‐Bonnet S, Hellenbrand W, Garbe E, et al. Safety and effectiveness of acellular pertussis vaccination during pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 136.

- 20. Rowe SL, Leder K, Perrett KP, et al. Maternal vaccination and infant influenza and pertussis. Pediatrics 2021; 148: e2021051076.

- 21. Queensland Department of Health. First Nations COVID‐19 vaccination training. 2022. https://clinicalexcellence.qld.gov.au/showcase/events/showcase‐2022/care‐for‐mob/covid‐vaccination‐training.html (viewed Nov 2023).

Abstract

Objectives: To evaluate the effectiveness of maternal pertussis vaccination for preventing pertussis infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants under seven months of age.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study; analysis of linked administrative health data.

Setting, participants: Mother–infant cohort (Links2HealthierBubs) including all pregnant women who gave birth to live infants (gestational age ≥ 20 weeks, birthweight ≥ 400 g) in the Northern Territory, Queensland, and Western Australia during 1 January 2012 – 31 December 2017.

Main outcome measures: Proportions of women vaccinated against pertussis during pregnancy, rates of pertussis infections among infants under seven months of age, and estimated effectiveness of maternal vaccination for protecting infants against pertussis infection, each by Indigenous status.

Results: Of the 19 892 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who gave birth to live infants during 2012–2017, 7398 (37.2%) received pertussis vaccine doses during their pregnancy, as had 137 034 of 259 526 non‐Indigenous women (52.8%; Indigenousv non‐Indigenous: adjusted odds ratio, 0.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62–0.70). The annual incidence of notified pertussis infections in non‐Indigenous infants declined from 16.8 (95% CI, 9.9–29) in 2012 to 1.4 (95% CI, 0.3–8.0) cases per 10 000 births in 2017; among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants, it declined from 47.6 (95% CI, 16.2–139) to 38.6 (95% CI, 10.6–140) cases per 10 000 births. The effectiveness of maternal vaccination for protecting non‐Indigenous infants under seven months of age against pertussis infection during 2014–17 was 68.2% (95% CI, 51.8–79.0%); protection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants was not statistically significant (36.1%; 95% CI, –41.3% to 71.1%).

Conclusions: During 2015–17, maternal pertussis vaccination did not protect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants in the NT, Queensland, and WA against infection. Increasing the pertussis vaccination rate among pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women requires culturally appropriate, innovative strategies co‐designed in partnership with Indigenous organisations and communities.