The implementation of a national Lung Cancer Screening Program (LCSP), commencing in July 2025, presents a significant opportunity to have an impact on an intractable health problem for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.1 Lung cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer death for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.2 The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander age‐standardised incidence rate was 85.2 cases per 100 000 for 2009–2013 and the mortality rate was 56.8 deaths per 100 000, which are double the rates found in non‐Indigenous populations.2 Lung cancer mortality rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are increasing, in contrast to falling rates in non‐Indigenous Australians.2 These diverging trends are expected to increase disparities for many years to come and clearly demonstrate the health system is failing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The disproportionate lung cancer burden means that an LCSP could deliver greater benefits to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and reduce the disparity with non‐Indigenous Australians.

International trials demonstrate the clinical effectiveness and potential benefits of an LCSP, through low dose computed tomography (LDCT), including identifying disease at an early stage where survival rates are substantially improved.3,4 The outcomes of existing LCSPs in high income countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom show these results can be achieved in communities with high levels of socio‐economic deprivation (eg, Lung Health Check in the UK).5 Aotearoa New Zealand has demonstrated the cost‐effectiveness of an LCSP to reduce population level inequities in lung cancer for the Māori population. Māori people will achieve greater per capita health gains compared with non‐Māori people due to higher rates of tobacco use and higher incidence and mortality from lung cancer.6 Currently, there are Māori‐led implementation trials to provide evidence on strategies that optimise an LCSP for the Māori population, including determining the most effective recruitment strategies (comparing participation via general practitioners versus a central hub).7

Australia is to implement a national LCSP, with the Australian Government funding a risk‐tailored LCSP. The program will identify and refer individuals aged 50–70 years with a history of cigarette smoking of at least 30 pack‐years, and, if they had formally smoked, had quit within the previous ten years, for an LDCT scan via a medical practitioner.3,8

An understanding of historical and cultural contexts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing in a settler colonial state is essential. Tobacco use and lower rates of participation in existing cancer screening programs reflect the legacy of over two centuries of racism, colonisation, genocide and dispossession of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, creating the social, economic and political context for health care exclusion. A one‐size‐fits‐all approach will not work, as already evidenced in the broader health care system. An equitable LCSP requires ensuring a good fit between the program and the specific contexts within which it will be implemented.9

Although the need for an equitable approach to an LCSP in Australia has been previously identified,3 much remains unknown about suitable implementation strategies to meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities. The 2023–24 federal budget included funding to ensure mainstream cancer care services are culturally safe and accessible to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.10 However, we argue that an equity lens must be applied to designing and implementing an LCSP with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation at the core of program design rather than a post hoc alteration to a mainstream program. Principles to guide the codesign of an LCSP with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do exist.11,12 To ensure equitable access, the design of an LCSP must address known barriers to existing cancer screening programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, while gathering LCSP‐specific evidence of enablers to implementation.

Leveraging knowledge from existing cancer screening programs

Existing bowel, breast and cervical cancer screening programs have failed to provide equitable outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, with low reported participation, high screening positivity, low diagnostic assessment rates, and high age‐standardised incidence and mortality for these cancers.2,13,14,15

Barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples participating in existing cancer screening programs are known and include understanding the benefits of screening, fear or shame associated with the screen or cancer diagnosis, and a lack of awareness of cancer screening.16,17 US research indicates that low awareness of the LCSP and its benefits is a significant barrier to engaging communities.18

Known logistical barriers to screening participation, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in rural and remote communities, include transport, accommodation and associated costs.16,19 Service level barriers include a lack of culturally safe services and communication and language barriers.20 Culturally safe services comprise practitioners who have reflected on and understand how their cultural identity shapes their health care practice and can then apply this knowledge to provide safe, respectful and empowering care to a person of another culture.12 These long‐standing structural barriers embedded broadly into the health system result in exclusion or inappropriate care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and lead to mistrust of mainstream health services.20

The complexity of lung cancer screening presents additional challenges

The LCSP may result in additional barriers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ participation. LCSP requirements for targeted recruitment, complex shared decision‐making processes, and referral for an LDCT by a GP will place additional resource implications on an already scarce and limited workforce servicing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.21 Access barriers faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living across rural and remote Australia need to be addressed, for example, through a mobile lung cancer LDCT screening program.

Lung cancer risk assessment tools that inform LDCT referral decisions have not yet been validated in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. Validation will require engagement with key stakeholders to identify critical risk factors, the ability to routinely collect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status in the health services that provide lung cancer investigation and management, and ensuring that race is not used as a proxy factor for more relevant socio‐economic risk factors.22

Delivery of lung cancer screening must be culturally safe and appropriate

Promoting awareness of lung cancer screening and its benefits among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and health professionals who work with them is fundamental to access. Successful promotional strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples used in existing cancer screening programs include promotional campaigns tailored to local communities, the use of peer educators and community champions, and promoting positive messages and emotions toward screening, could inform LCSP strategies.16,17

Developing strong, trusting relationships with clinicians and health services, is effective in increasing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in breast and cervical screening programs20,23 and will be important in an LCSP. BreastScreen Australia has had a focus on cultural safety through codesign of resources and a flexible approach to service delivery, including the use of mobile vans. Similarly, bowel screening participation increased in a pilot of an alternative pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples developed in consultation with communities, which resulted in the distribution and explanation of tests via known and trusted local health care workers.24 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health care professionals and services are essential to building strong relationships. Aboriginal community controlled health services have enabled and fostered culturally safe programs and access to cancer screening programs through initiatives such as making group bookings for community members and providing group travel to and from screening.17,25

Smoking cessation is integral to an LCSP, and trials have demonstrated higher quit rates than in the general population.3 As smoking is a leading contributor to disease burden for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, smoking cessation delivered through an LCSP is an important primary prevention mechanism for lung cancer as well as delivering other health benefits. Referring to established and successful culturally safe smoking cessation services will be essential to the long term success of the program, particularly for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples for whom, despite impressive declines in smoking prevalence, smoking rates remain high.26

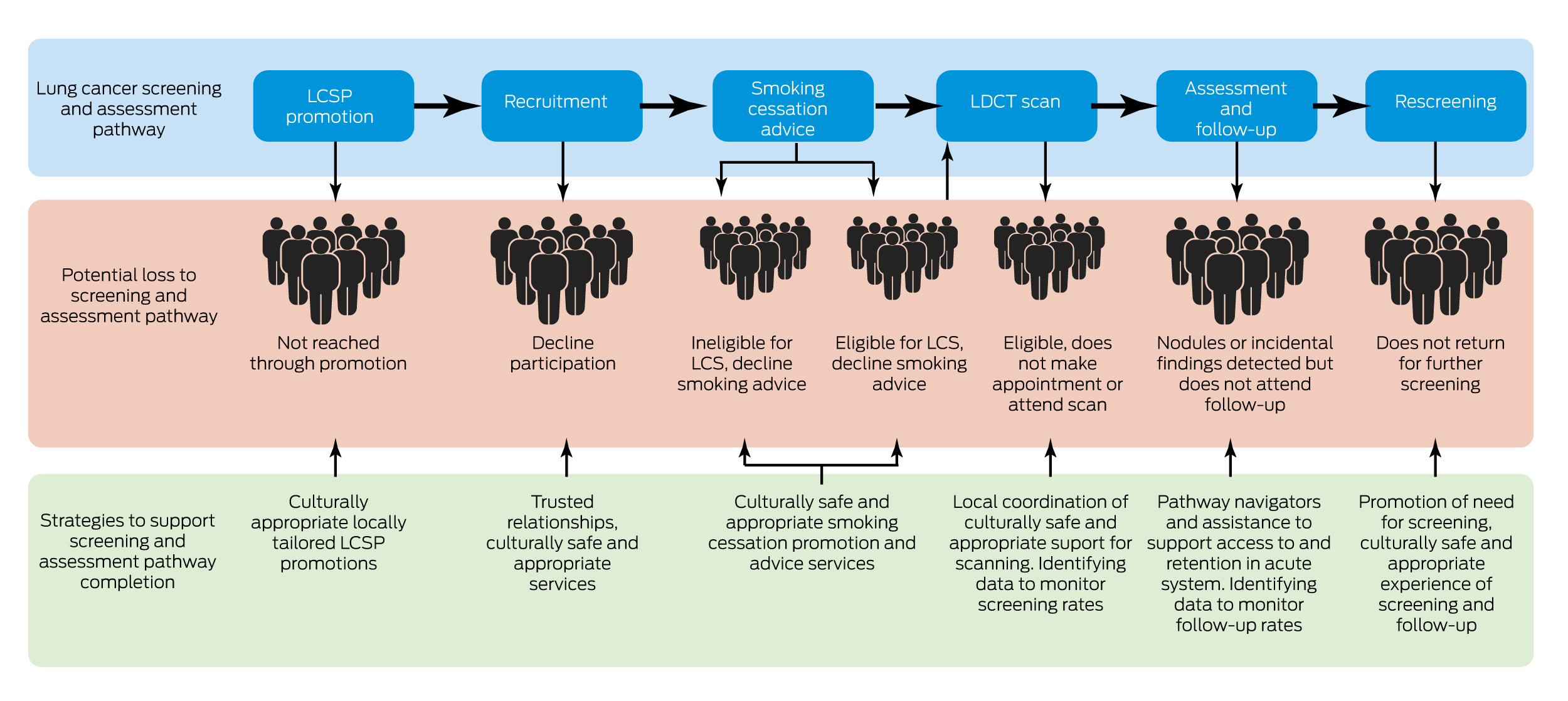

Access to a culturally safe LCSP is essential as is timely referral and access to health services for participants who require follow‐up after an LDCT scan. Access to navigators (culturally safe trained health care workers) to navigate specialist and hospital appointments to overcome structural barriers to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants accessing mainstream services is needed to realise the benefits of early lung cancer detection.27,28 This navigation role could be extended more broadly across the lung cancer screening and assessment pathway and into the mainstream health system. Strategies to be codesigned with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations to support the LCSP completion are summarised in Box 1.

A call to action: an equitable Australian lung cancer screening program is essential

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders, organisations and people with lived experience of lung cancer must drive the design of an equitable LCSP including tailoring program promotion, workforce development, and program delivery to a range of contexts in which the program will be delivered. A commitment to culturally appropriate codesign processes will shape the development of an equitable lung cancer screening pathway. The key elements of an equitable LCSP for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples underpinned by the principles of codesign are outlined in Box 2.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations have the most to gain from an equitable approach to implementation and, conversely, the greater burden to bear if population‐specific implementation barriers are not identified and addressed as part of an LCSP. An equitable LCSP will ensure that potentially underscreened populations are able to participate through culturally safe and appropriate screening and service delivery models. Applying the principle of proportionate universalism, increasing services and resourcing in line with the gradient of health need,30 will be essential to achieving equity.

Box 1 – Strategies to support the completion of the lung cancer screening and assessment pathway

LCS = lung cancer screening; LCSP = Lung Cancer Screening Program; LDCT = low dose computed tomography.

Box 2 – Call to action for lung cancer screening (LCS)

|

Key elements of an equitable LCSP |

Examples of how to achieve an equitable LCSP |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

An equitable LCS pathway is codesigned through a process that is guided at all stages by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership at all levels and from the range of diverse communities |

Leadership such as:

|

||||||||||||||

|

Benefits of LCS are identified by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and not presumed by others |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Lessons learned from existing cancer screening programs are incorporated |

|||||||||||||||

|

Implementation of LCS pathway for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is accountable to and overseen by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leadership |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

LCSP = Lung Cancer Screening Program; VACCHO = Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Commonwealth of Australia. Portfolio Budget Statements 2023–24 Budget related paper No. 1.9 — Health and Aged Care Portfolio. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐05/health‐portfolio‐budget‐statements‐budget‐2023‐24.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People of Australia [Cat. No. CAN 109]. Canberra: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer/cancer‐in‐indigenous‐australians/contents/about (viewed Aug 2023).

- 3. Cancer Australia. Report on the Lung Cancer Screening enquiry. Sydney: Cancer Australia, 2020. https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/publications‐and‐resources/cancer‐australia‐publications/report‐lung‐cancer‐screening‐enquiry (viewed Aug 2023).

- 4. O'Dowd EL, Ten Haaf K. Lung cancer screening: enhancing risk stratification and minimising harms by incorporating information from screening results. Thorax 2019; 74: 825‐828.

- 5. Hinde S, Crilly T, Balata H, et al. The cost‐effectiveness of the Manchester “lung health checks”, a community‐based lung cancer low‐dose CT screening pilot. Lung Cancer 2018; 126: 119‐124.

- 6. McLeod M, Sandiford P, Kvizhinadze G, et al. Impact of low‐dose CT screening for lung cancer on ethnic health inequities in New Zealand: a cost‐effectiveness analysis. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e037145.

- 7. Health Research Council of New Zealand. Māori‐led trial of lung cancer screening a first for New Zealand. Auckland: HRCNZ, 2021. https://hrc.govt.nz/news‐and‐events/maori‐led‐trial‐lung‐cancer‐screening‐first‐new‐zealand (viewed Aug 2023).

- 8. Medical Services Advisory Committee. MSAC Outcomes — Public Summary Document: application No. 1699 – National Lung Cancer Screening. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. http://www.msac.gov.au/internet/msac/publishing.nsf/Content/1699‐public (viewed Aug 2023).

- 9. Baumann AA, Cabassa LJ. Reframing implementation science to address inequities in healthcare delivery. BMC Health Serv Res 2020; 20: 190.

- 10. Department of Health and Aged Care. Taking action on smoking and vaping [media release]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the‐hon‐mark‐butler‐mp/media/taking‐action‐on‐smoking‐and‐vaping (viewed Aug 2023).

- 11. Anderson K, Gall A, Butler T, et al. Development of key principles and best practices for co‐design in health with First Nations Australians. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 147.

- 12. Butler T, Gall A, Garvey G, et al. A comprehensive review of optimal approaches to co‐design in health with First Nations Australians. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19: 16166.

- 13. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Analysis of cancer outcomes and screening behaviour for national cancer screening programs in Australia [Cat. No. CAN 115]. Canberra: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer‐screening/cancer‐outcomes‐screening‐behaviour‐programs/summary (viewed Aug 2023).

- 14. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. BreastScreen Australia monitoring report 2019 [Cat. No. CAN 128]. Canberra: AIHW, 2019. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/dab466c6‐1e5c‐425d‐bd1f‐c5d5bce8b5a9/aihw‐can‐128.pdf.aspx?inline=true (viewed Aug 2023).

- 15. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: monitoring report 2020 [Cat. No. CAN 133]. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer‐screening/national‐bowel‐cancer‐screening‐monitoring‐2020/summary (viewed Aug 2023).

- 16. Moxham R, Moylan P, Duniec L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, intentions and behaviours of Australian Indigenous women from NSW in response to the National Cervical Screening Program changes: a qualitative study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2021; 13: 100195.

- 17. Pilkington L, Haigh MM, Durey A, et al. Perspectives of Aboriginal women on participation in mammographic screening: a step towards improving services. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 697.

- 18. American Lung Association. 2022 Lung Health Barometer media summary. Chicago (IL): ALA, 2022. https://www.lung.org/getmedia/5becd092‐6a85‐41c7‐b42f‐a37ca2c27f7d/lf‐barometer‐media‐summary‐2022‐final.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 19. Butler TL, Anderson K, Condon JR, et al. Indigenous Australian women's experiences of participation in cervical screening. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0234536.

- 20. Whop LJ, Smith MA, Butler TL, et al. Achieving cervical cancer elimination among Indigenous women. Prev Med 2021; 144: 106314.

- 21. Ireland K, Hendire D, Ledwith T, Singh A. Strategies to address barriers and improve bowel cancer screening participation in Indigenous populations, particularly in rural and remote communities: a scoping review. Health Promot J Austr 2023; 34: 544‐560.

- 22. Waters EA, Colditz GA, Davis KL. Essentialism and exclusion: racism in cancer risk prediction models. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021; 113: 1620‐1624.

- 23. Butler TL, Lee N, Anderson K, et al. Under‐screened Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women's perspectives on cervical screening. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0271658.

- 24. Menzies School of Health Research. National Indigenous Bowel Screening Pilot: final report. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/06/final‐report‐on‐the‐national‐indigenous‐bowel‐screening‐pilot.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 25. Haigh M, Burns J, Potter C, et al. Review of cancer among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Perth: Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin, 2018. https://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/review‐of‐cancer‐2018/ (viewed Aug 2023).

- 26. National Indigenous Australian Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Performance Framework, Tier 2 — Determinants of Health. 2.15 Tobacco use. Canberra: AIHW, 2023. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/2‐15‐tobacco‐use#:~:text=By%20remoteness%2C%20the%20proportion%20of,and%2038%25%2C%20respectively (viewed Aug 2023).

- 27. Shahid S, Finn LD, Thompson SC. Barriers to participation of Aboriginal people in cancer care: communication in the hospital setting. Med J Aust 2009, 190: 574‐579. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2009/190/10/barriers‐participation‐aboriginal‐people‐cancer‐care‐communication‐hospital

- 28. Meiklejohn JA, Garvey G, Bailie R, et al. Follow‐up cancer care: perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2017; 25: 1597‐1605.

- 29. Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. The Beautiful Shawl Project. Melbourne: VACCHO, 2023. https://www.vaccho.org.au/beautiful‐shawl‐project/ (viewed Aug 2023).

- 30. Marmot M. Fair society, healthy lives. Florence: Leo S Olschki, 2013.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley – The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Lisa Whop is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator Grant (2009380). Gail Garvey is funded by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (1176651). Claire Nightingale is supported by a Mid‐Career Research Fellowship (MCRF21039) from the Victorian Government acting through the Victorian Cancer Agency. Nicole Rankin is funded by an NHMRC Ideas Grant (2019/GA65812) and a Medical Research Future Fund Grant (2019/MRF2008603). The funding sources had no role in the content of this article.

We received funding from Cancer Australia for conducting consultations with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce around lung cancer screening but we were not directly funded for the publication of this article.