Our stressed health system needs innovative solutions to care adequately for people with post‐COVID‐19 conditions

The post-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) condition or syndrome (“long COVID”) is defined as the persistence of existing symptoms or the development of new symptoms, without an alternative explanation, three months after an initial acute severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. The symptoms, of varying and inconstant severity, can impair everyday functioning. Although long COVID can affect many body systems, the most frequent symptoms are fatigue, shortness of breath, and cognitive dysfunction.1 Long COVID lasting more than twelve weeks is estimated to affect 5–10% of people in Australia who have had COVID-19,2 but lower rates following SARS-CoV-2 infections since 2022 have recently been reported in the United Kingdom (4.0% of first infections in adults, 2.4% of re-infections).3

Long COVID is precisely the kind of challenge the current Australian health system finds most difficult: a non‐fatal, chronic condition manifested as complex combinations of symptoms, without a simple diagnostic test or definitive pharmacotherapy, and causing distress to people with the disorder, who may need considerable face‐to‐face and other contact care. Responding to long COVID will require improved access to coordinated, multidisciplinary, team‐based care, supported by more efficient health information systems and digital tools, as outlined in the recent Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report.4 Additional challenges include uncertainty about the risk factors, incidence, and prevalence of long COVID.5,6 People with long COVID, especially those with severe functional disability, have felt unsupported, socially stigmatised, isolated, and, at times, not taken seriously by health professionals.7

Determining who has long COVID remains a key problem. A standardised, functional, clinical definition is essential for epidemiological purposes and to facilitate access to appropriate care, but none is universally accepted. The definition endorsed by the World Health Organization1 provides a framework currently used in Australia and elsewhere for clinical purposes, but it needs to be updated and applied to better serve the needs of people who need medical or psychological care, rehabilitation, and social or disability support, as well as the needs of public health care providers, planners, and policy makers. The definition must evolve with the evidence (new tests, functional assessment tools, validated treatments, social support pathways). Further, its wording must be clear to all Australians, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, and people with limited health literacy. It must also take developmental influences in younger children into account.

In Australia, health system planning for long COVID is constrained by the paucity of data on its incidence, clinical manifestations, and its effects in different risk groups, geographic locations, and health care settings. Published studies are small, local, and predominantly involve people previously hospitalised with acute COVID‐19. Ongoing monitoring of the prevalence, severity, prognosis, and other aspects of long COVID is essential for health system planning, but no nationally consistent health information system provides basic data on the numbers of cases seen in primary or ambulatory care. The United Kingdom Office of National Statistics Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Infection Survey3 is an example that the Australian Bureau of Statistics could profitably emulate.

A health care system capable of change with the right approach and support

COVID‐19 has already driven changes in Australian primary care, including a shift to telehealth services, systems that have achieved greater than 80% COVID‐19 vaccination coverage,8 and the establishment of general practitioner‐led respiratory clinics.9 However, while guidance is available,10 problems for implementing person‐centred and integrated models in primary care remain. The primary care system is under strain: workforce shortages and the decline in bulkbilling have reduced accessibility, especially in rural and remote areas.4 Person‐centred and integrated attention to the biopsychosocial components of long COVID and the added complexities of caring for people with other medical conditions will require further structural innovation. Co‐designing service solutions with patients is essential for improving the experience and outcomes of long COVID care.5,7 Widespread translation into practice requires more than guidelines: specific implementation science skills and tools are essential.

Intersectoral integrated care and active self‐management

While primary care assessment, management, and triaging of people who may have long COVID are vital, better coordination of multidisciplinary care across health and social care sector boundaries and better mobilisation of medical specialist, social worker, and allied health professional resources are needed. This requires reform beyond the primary care focus of the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report.4

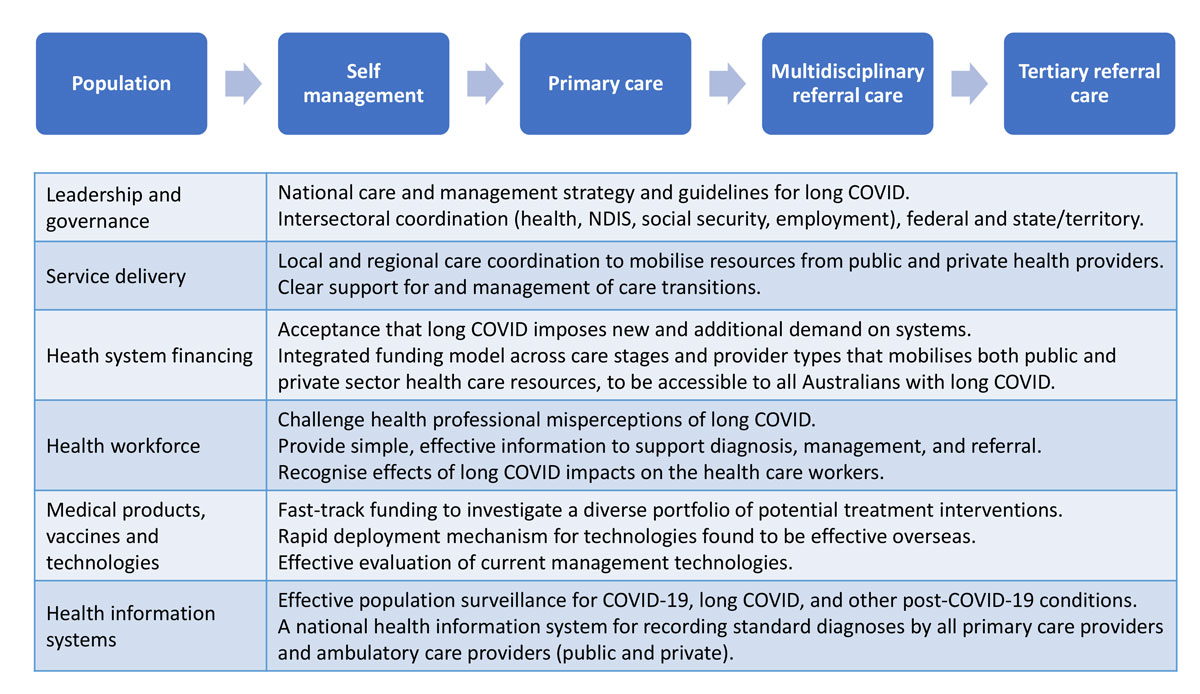

Potential strategies include a screening hierarchy of self‐assessment, telehealth, multidisciplinary community care and social support, and appropriate specialist referral and rehabilitation pathways (Box). We must ensure equitable access to services (including in our rural and remote communities), an adequate and informed health care workforce, and a community provided with well defined, consistent guidelines. Moreover, people should be empowered, as far as possible, to manage aspects of their condition themselves, as exemplified by the NHS digital resource Your Covid Recovery (https://www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk). With these health system elements in place, we would be on the way to an effective response to long COVID. Further, such changes would also assist people with other chronic conditions that constitute the major burden of disease for at least one in two Australians.12

Box – A comprehensive health system response to long COVID*

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NDIS = National Disability Insurance Scheme.* Effective support for people with long COVID of differing levels of severity and complexity requires a comprehensive, integrated continuum of services from population‐level surveillance and prevention through to referral to specialist services (top sequence). Developing this comprehensive pathway requires action across each of the WHO Health System Building Blocks (table).11

Provenance: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

- 1. World Health Organization. A clinical case definition of post COVID‐19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Geneva: WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐2019‐nCoV‐Post_COVID‐19_condition‐Clinical_case_definition‐2021.1 (viewed April 2023).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Long COVID in Australia: a review of the literature (AIHW cat. no. PHE 318). 16 Dec 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/covid‐19/long‐covid‐in‐australia‐a‐review‐of‐the‐literature/summary (viewed Apr 2023).

- 3. Office for National Statistics (UK). New‐onset, self‐reported long COVID after coronavirus (COVID‐19) reinfection in the UK. 23 Feb 2023. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/newonsetselfreportedlongcovidaftercoronaviruscovid19reinfectionintheuk/23february2023 (viewed Apr 2023).

- 4. Australian Government. Strengthening Medicare Taskforce report. Dec 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐02/strengthening‐medicare‐taskforce‐report_0.pdf (viewed Apr 2023).

- 5. Alwin NA. The road to addressing long COVID. Science 201; 373: 491‐493.

- 6. Saunders C, Sperling S, Bendstrup E. A new paradigm is needed to explain long COVID. Lancet Respir Med 2023; 11: e12‐e13.

- 7. Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport (Parliament of Australia). Impacts of long COVID and repeated COVID infections [Hansard]. 17 Feb 2023. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Hansard/Hansard_Display?bid=committees/commrep/26500/&sid=0007 (viewed Apr 2023).

- 8. Kidd M, de Toca L. The contribution of Australia's general practitioners to the COVID‐19 vaccine rollout. Aust J Gen Pract 2021; 50: 871‐872.

- 9. Kidd M. Five principles for pandemic preparedness: lessons from the Australian COVID‐19 primary care response. Br J Gen Pract 2020; 70: 316‐317.

- 10. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Caring for patients with post‐COVID‐19 conditions. Melbourne: RACGP, 2022. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical‐resources/covid‐19‐resources/clinical‐care/caring‐for‐patients‐with‐post‐covid‐19‐conditions/introduction (viewed Apr 2023).

- 11. World Health Organization. Everybody's business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO's framework for action. Geneva: WHO, 2007. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43918/9789241596077_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (viewed Apr 2023).

- 12. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic disease. Updated 3 Feb 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports‐data/health‐conditions‐disability‐deaths/chronic‐disease/overview (viewed Apr 2023).

- 13. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport. Sick and tired: casting a long shadow. Inquiry into long COVID and repeated COVID infections. Apr 2023. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Health_Aged_Care_and_Sport/LongandrepeatedCOVID/Report (viewed Apr 2023).

- 14. Minister for Health and Aged Care. $50 million for research in to long COVID [media release]. 24 Apr 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/ministers/the‐hon‐mark‐butler‐mp/media/50‐million‐for‐research‐in‐to‐long‐covid (viewed Apr 2023).

We acknowledge the work of the fellows of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences and the Australian Academy of Science and of other experts who contributed to a joint written submission to the Parliamentary Inquiry into Long COVID and Repeated COVID Infections and a subsequent roundtable discussion with the Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport. The final report of the Standing Committee was released on 24 April 2023.13 The Minister for Health and Aged Care, the Hon. Mark Butler MP, subsequently announced that $50 million would be provided from the Medical Research Future Fund for long COVID research.14

Martin Hensher was a member of the National COVID‐19 Health and Research Advisory Committee Working Group on Long COVID (unremunerated). Lena Sanci co‐leads the long COVID project in APPRISE (Australian Partnership for Preparedness Research on Infectious Disease Emergencies, a Centre for Research Excellence. Tania Sorrell is a chief investigator and an executive member of APPRISE, but has received no remuneration in relation to the Long COVID project.