Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a multisystem disorder characterised by productive cough and recurrent chest infections linked with bronchiectasis; extrapulmonary symptoms may include gastrointestinal reflux, malnutrition associated with pancreatic insufficiency, and chronic sinus disease.1 With multidisciplinary care and improving therapeutic options, the median life expectancy for people with CF is now almost 50 years of age.1 In 2022, highly effective modulator therapy (elexacaftor–tezacaftor–ivacaftor) was made available to all Australians with CF aged 12 years or more with at least one F508del‐CFTR mutation (present in 90% of people with CF),1 with dramatic clinical benefits.2,3

Most people with CF are diagnosed during newborn screening or while still young, but as many as 10% are only diagnosed as adults, most because they were born before newborn screening was introduced or because of the limitations of earlier screening strategies.4 Here we describe the characteristics of adults (18 years or older) with confirmed CF according to current diagnostic guidelines, who were listed in the Australian CF data registry (ACFDR) during 1 January 2000 – 31 December 2019. In 2020, data completeness for the ACFDR was 95.5%.5 Data were censored at the final documented interaction with the ACFDR while the patient was alive, or at the time of an event (transplantation or death). CF‐related complications were assessed when the information was available, including pancreatic insufficiency, diabetes, and microbiological airway colonisation. The study protocol was approved by the Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (references, X20‐0421; STE04158).

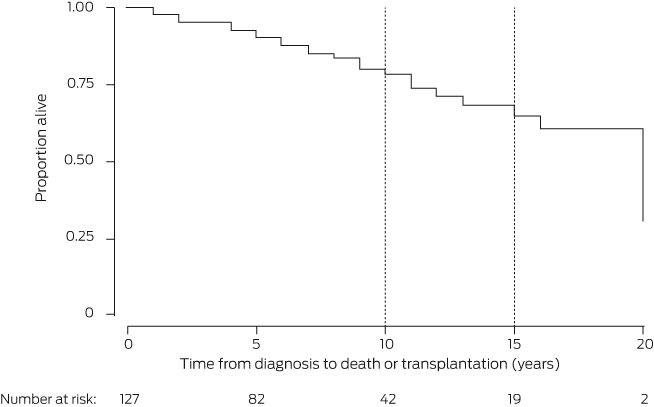

CF was diagnosed during adulthood in 146 people, or 4.5% of the 3446 people registered by the ACFDR in 2019 (Box 1).2 Fourteen people (10%) were lost to follow‐up; the median follow‐up time for the others was seven years (interquartile range, 3–12 years). In Kaplan–Meier analyses, we estimated that 10‐year transplant‐free survival for the entire cohort was 78.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 67.2–86.1%) and 15‐year survival was 64.9% (95% CI, 49.6–76.5%) (Box 2). That is, life expectancy for people diagnosed as adults with CF was lower than for the general Australian population (at least 80 years of age).6

We identified features of CF diagnosed during adulthood in Australia that may differ from the classic CF phenotype. First, 34 of 109 adults for whom the CF diagnosis was suggested by clinical features (31%) presented with non‐respiratory symptoms, such as gastrointestinal disease and infertility (Box 1). Other features reported at diagnosis in some cases included chronic sinus disease and family history of CF (data not shown). Second, adults with CF diagnosed were generally well nourished (based on body mass index) and had mildly reduced lung function (based on forced expiratory volume in one second). Third, 109 of 146 adults (75%) had at least one F508del mutation. While evidence of Pseudomonas colonisation was infrequent at diagnosis (9 of 109, 8%), it was later identified in 35 of 62 patients (56%). Finally, although the disease course was milder than for infants and children diagnosed with CF, lung transplant‐free survival was still shorter than for people without CF.

Detailed data for some variables, such as treatment, were not captured by the ACFDR until 2019. Further, as the registry could be linked with National Death Index data only from 2019, ascertainment bias may have affected our results.

Our findings indicate that CF diagnosed in adults may manifest with milder symptoms across a range of organ systems than classical CF. High clinical suspicion is consequently needed by specialists and general practitioners to expedite its diagnosis.

Box 1 – Demographic and clinical characteristics of 146 adults diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, Australia, 1 January 2000 – 31 December 2019, by outcome*

|

Characteristic |

All people with cystic fibrosis |

Transplantation or death |

People with censored data |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of people |

146 |

25 |

107 |

||||||||||||

|

Age at diagnosis (years) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Median (IQR) |

34.7 (26.5–45.7) |

39.9 (32.9–57.2) |

34.0 (26.4–44.1) |

||||||||||||

|

18–30 |

49 (34%) |

5 (20%) |

40 (37%) |

||||||||||||

|

31–50 |

67 (46%) |

10 (40%) |

50 (47%) |

||||||||||||

|

Over 50 |

30 (20%) |

10 (40%) |

17 (16%) |

||||||||||||

|

Age at death/transplantation, (years), median (range) |

— |

48 (30–77) |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Sex (men) |

73 (50%) |

13 (52%) |

52 (49%) |

||||||||||||

|

FEV1 (% predicted), median (IQR)† |

75.8 (56.7–92.8) |

41.6 (36.1–67.5) |

79.0 (63.6–93.2) |

||||||||||||

|

Body mass index (kg/m2), median (IQR)† |

24.2 (21.6–24.2) |

22.0 (20.6–24.6) |

24.6 (22.1–27.8) |

||||||||||||

|

Genetic mutations |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

F508del homozygous |

6 (4%) |

2 (8%) |

3 (3%) |

||||||||||||

|

F508del heterozygous |

103 (70%) |

18 (72%) |

76 (71%) |

||||||||||||

|

Other mutation |

37 (25%) |

5 (20%) |

28 (26%) |

||||||||||||

|

Clinical features at diagnosis |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Respiratory signs and symptoms |

70/109 (64%) |

16/23 (70%) |

51/76 (67%) |

||||||||||||

|

Infertility |

20/109 (18%) |

2/23 (9%) |

16/76 (21%) |

||||||||||||

|

Gastrointestinal symptoms |

14/109 (13%) |

2/23 (9%) |

9/76 (12%) |

||||||||||||

|

Abnormal respiratory imaging |

12/109 (11%) |

2/23 (9%) |

9/76 (12%) |

||||||||||||

|

Airway colonisation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa at diagnosis |

9/109 (8%) |

2/23 (9%) |

7/76 (9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Non‐tuberculous mycobacteria at diagnosis |

2/109 (2%) |

0/23 |

2/76 (3%) |

||||||||||||

|

Pancreatic sufficiency‡ |

81/119 (68%) |

11/21 (52%) |

62/88 (70%) |

||||||||||||

|

Cystic fibrosis‐related diabetes |

15/118 (13%) |

10/22 (46%) |

5/88 (6%) |

||||||||||||

|

Airway colonisation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ever) |

35/62 (56%) |

5/5 (100%) |

30/57 (53%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; IQR = interquartile range. * Fourteen people were lost to follow‐up. † Missing data: all people with CF, 15; transplantation or death, two; censored data, four. ‡ Pancreatic sufficiency recorded at diagnosis. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 18 April 2022, accepted 11 November 2022

- 1. Bell SC, Mall MA, Gutierrez H, et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: 65‐124.

- 2. Australian Department of Health. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) meeting outcomes: December 2021 PBAC meeting. https://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac‐meetings/pbac‐outcomes/2021‐12/December%202021%20PBAC%20Web%20Outcomes.pdf (viewed Feb 2022).

- 3. Middleton PG, Mall MA, Drevinek P, et al; VX17‐445‐102 Study Group. Elexacaftor–tezacaftor–ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1809‐1819.

- 4. Massie RJ, Curnow L, Glazner, et al. Lessons learned from 20 years of newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Med J Aust 2012; 196: 67‐70. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2012/196/1/lessons‐learned‐20‐years‐newborn‐screening‐cystic‐fibrosis

- 5. Ahern S, Salimi F, Caruso M, et al. The Australian Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry: annual report 2020; version 1.1. Updated July 2021. https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/the‐australian‐cystic‐fibrosis‐data‐registry‐annual‐report‐2020 (viewed Feb 2022).

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Life tables; reference period 2017–2019. Updated 4 Nov 2020. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/life‐tables/2017‐2019 (viewed Jan 2022).

We thank the Australian Cystic Fibrosis Data Registry for supporting this study. We also thank people with cystic fibrosis and their families who participate in the data registry.

No relevant disclosures.