Clinical record

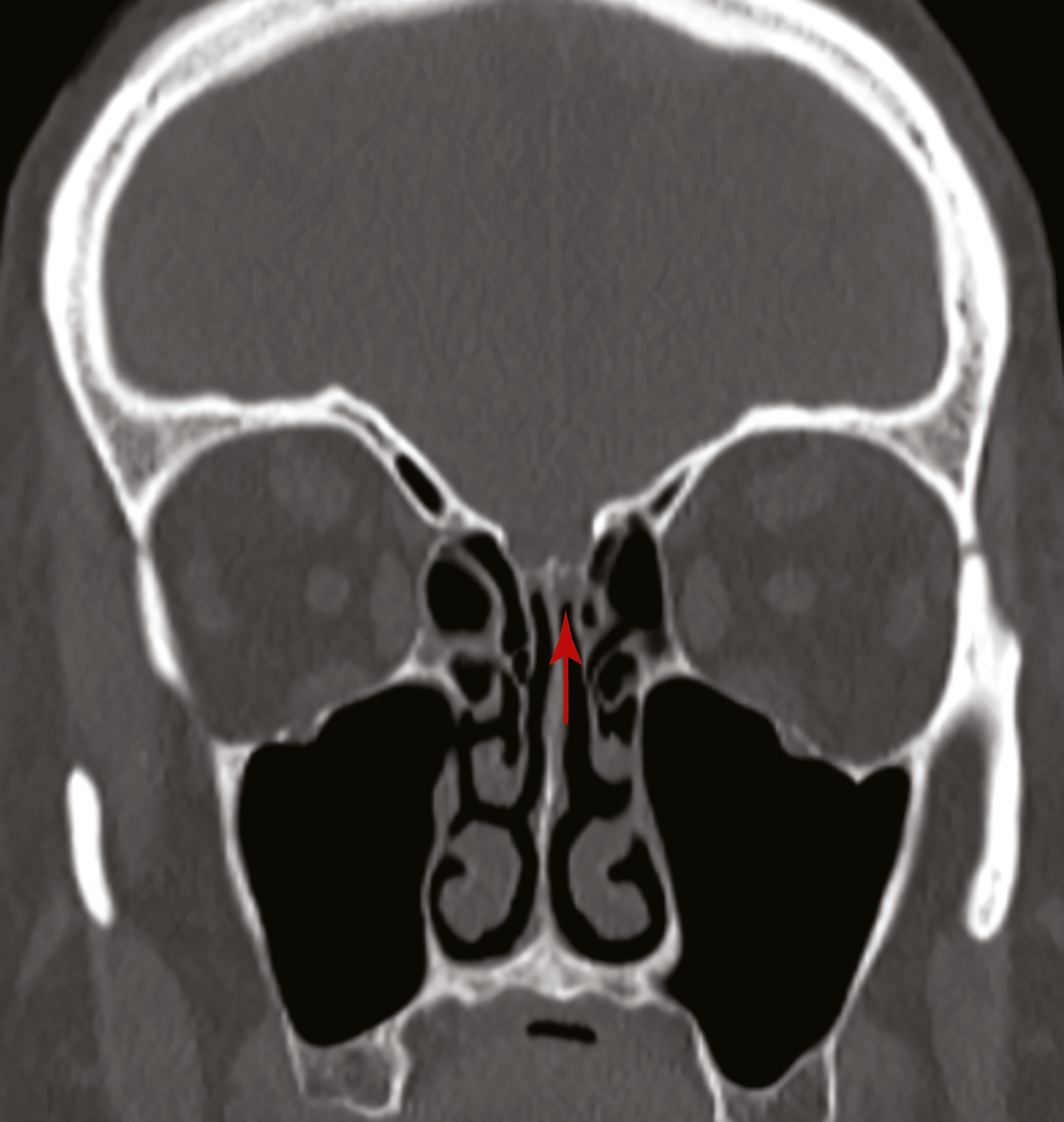

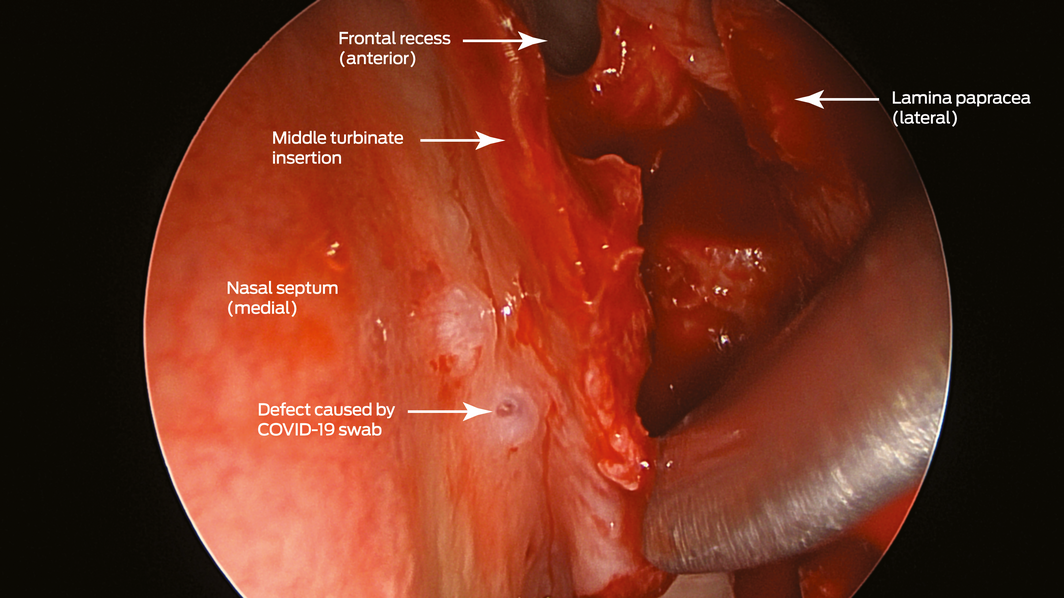

A 67‐year‐old woman was referred to our ear, nose and throat department with confirmed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea. She was recently treated for proven bacterial meningitis, having presented to a regional hospital with headache, nausea and photophobia 2 months previously. The patient precisely recalled the onset of unilateral clear rhinorrhoea, which occurred within hours of an “extremely painful” coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) swab test. This occurred approximately 48 hours prior to presentation to the emergency department. She had no other historical or medical risk factors for a CSF fistula (eg, previous surgery, trauma) nor harboured any stigmata of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Intra‐operative evaluation confirmed a small, well demarcated defect (2–3 mm) in the left anterior skull base in the posterior cribriform plate (Box 1 and Box 2). The defect was successfully repaired with a fat plug and free mucosa overlay graft. She made a full recovery and remains leak‐free. Given the historical description, time frame and clinical findings, we believe the injury to be a complication of the COVID‐19 swab.

Discussion

In response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, there has been an overarching public health goal to slow transmission rates. Instrumental to achieving this goal are mass testing and tracing programs to rapidly identify and isolate cases. While nasopharyngeal sampling is regarded as a safe procedure when performed correctly, our case highlights the occurrence of skull base injury during nasal swabbing. This represents a severe but rare complication of mass testing. At the time of writing, and to our knowledge, our case appeared to be the only such complication identified in Australia. This equates to a national incidence of skull base injury from COVID‐19 swab testing of one in 7 393 693.1 A 2020 report described a CSF leak following a COVID‐19 swab in a patient with a known history of idiopathic intracranial hypertension, nasal encephalocele and sinus surgery.2 Our case had no such pre‐existing history to confound the aetiology of the leak.

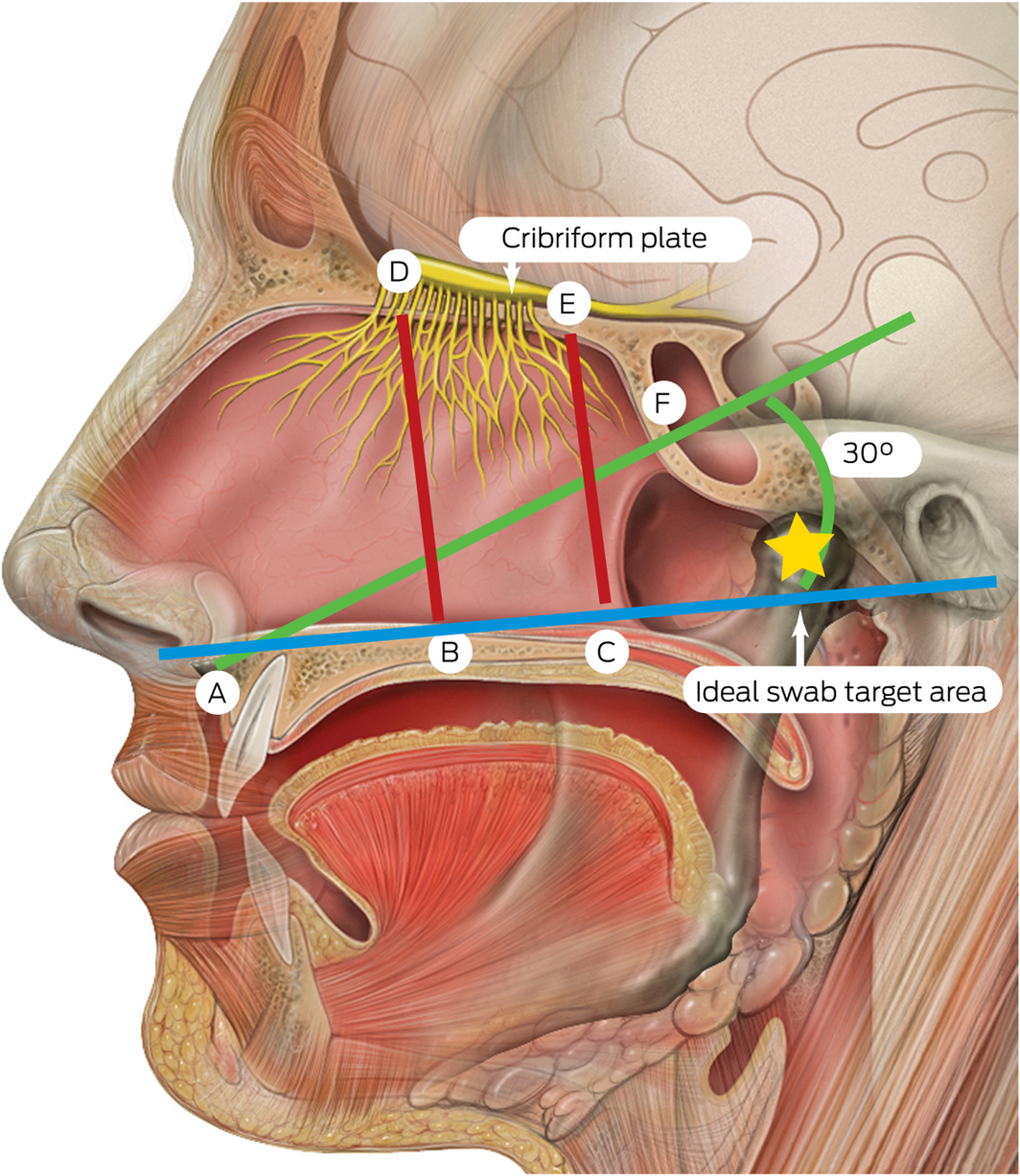

Safe techniques in obtaining deep nasal and nasopharyngeal swabs have been published by numerous public health authorities globally during the COVID‐19 pandemic.3,4 Although deep nasal swabs aiming to sample nasal mucosa at about 2–3 cm depth have been reported to be inferior to nasopharyngeal swabs, they are less invasive.3,4 In our opinion, descriptions of techniques for deep nasal and nasopharyngeal swabs may be easily confused by health care providers. It appears that a possible area for confusion relates to recommendations in patient positioning of a 70° angle of head extension.3 Confusion may occur where guidance does not reference the angle of swab insertion. In this setting, there is significant risk of damage to the skull base if the swab is introduced in a horizontal orientation in relation to the tester with excessive depth and force. A previous anatomical study identified measurements and angles of the skull base to key nasal landmarks.5 The average height from the nasal floor to the weakest area of the nasal roof (cribriform plate) is 45.73 mm (range, 38–52 mm) anteriorly within the nasal cavity (Box 3).5 The angle whereby the opening of the sphenoid sinus is encountered is about 30° from the horizontal at a distance of 61.50 mm (range, 43–69 mm) from the anterior nasal spine. Therefore, consideration must be taken by health care providers in relation to the swab length (135 mm at our institution) and angle of introduction to allow safe swab testing.

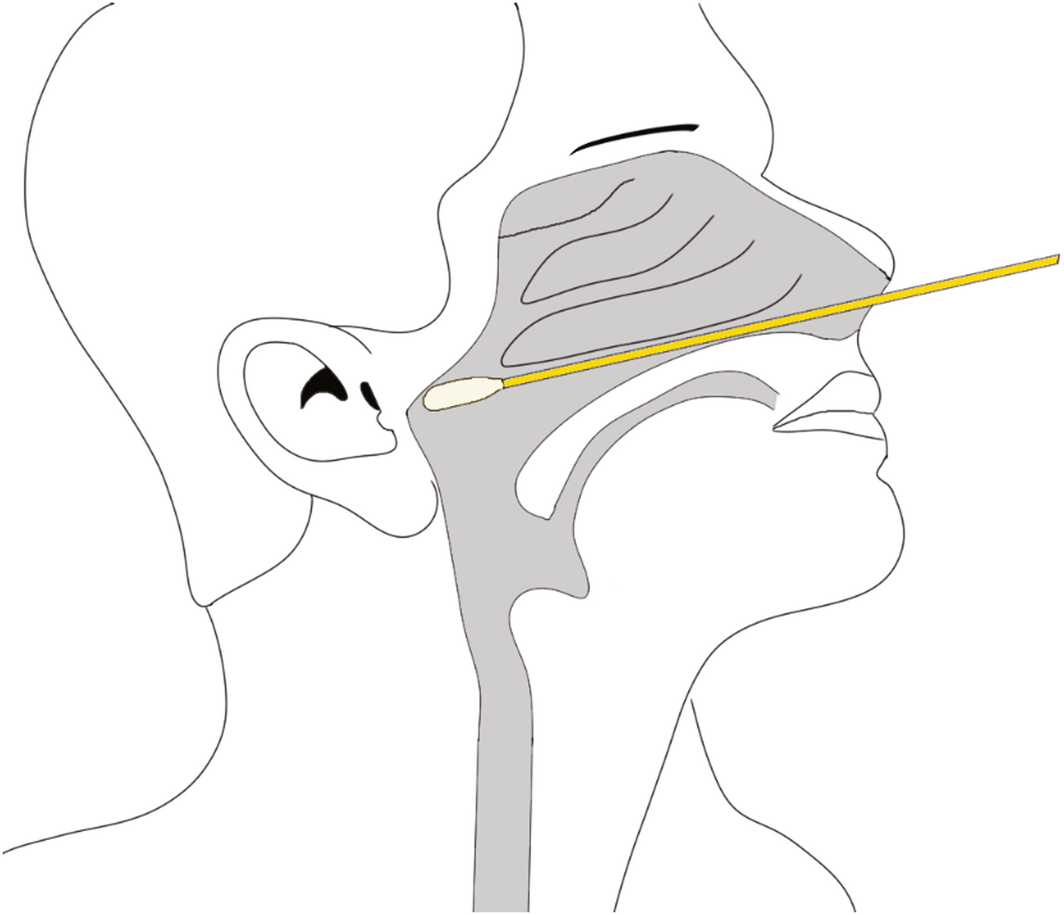

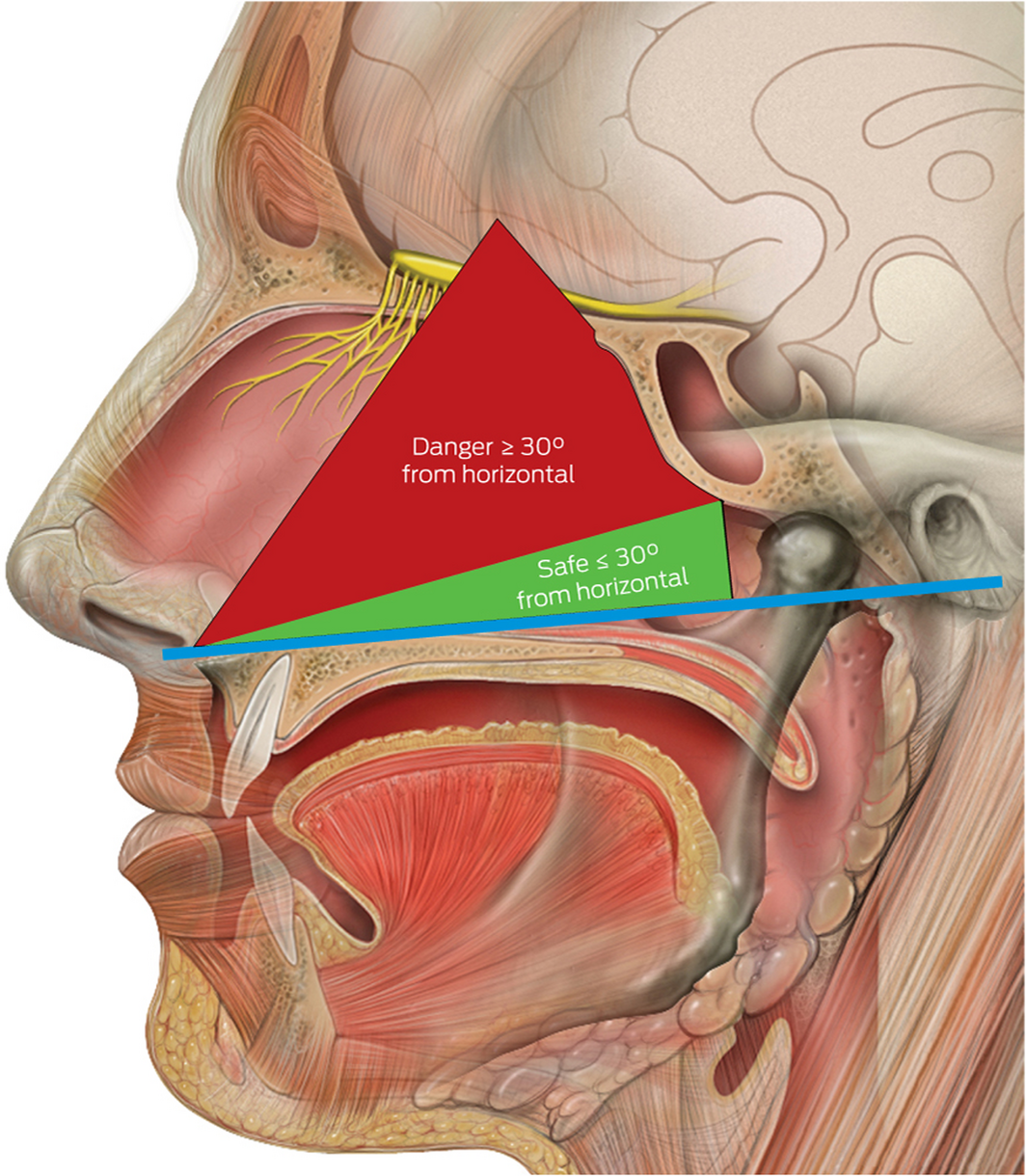

We recommend that a safe and effective approach for deep nasal and nasopharyngeal sampling does not depend on any head extension. More crucially, it involves swab insertion into the nasal cavity at a plane between the opening of the nose and the external ear canal on the patient, which can be considered as the horizontal plane for the purpose of relationship to surface anatomy (Box 4). This will allow the swab to be inserted parallel to the nasal floor, which would avoid injury to the middle turbinates. Swabs inserted in an upward orientation into the nasal cavity (> 30°) not only have a risk of failing to achieve an adequate diagnostic sample from the desired nasal mucosa and nasopharynx but also puts the patient at greater risk of injury to the thin and delicate areas of the skull base (attachment of middle turbinate and cribriform plate) which are superior and anterior to the sphenoid sinus ostium. Box 5 illustrates a safe arc for swabbing and the danger areas that should be avoided. We urge that this angle is not exceeded when performing diagnostic tests, as it places the patient at greatest risk of serious adverse events.

- Skull base injury and cerebrospinal fluid leak are a possible but very rare complication from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) swab testing.

- There have been limited reports of complications secondary to COVID‐19 nasopharyngeal swabs. As mass testing continues, the accumulation of reports of complications will be essential to improve practice.

- A 70° head extension exposes the skull base to injury if the tester performs the incorrect technique.

- Swabs must be inserted at a horizontal plane between the nasal opening and the external ear canal.

Box 1 – Coronal view of a computed tomography scan of the sinuses showing a defect in the left cribiform plate before the insertion of a fat plug (arrow)

Box 2 – Endoscopic view (45° endoscope) of the defect created by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) swab (left nasal cavity)

Box 3 – Measurements from the nasal floor to the skull base and sphenoid*,5

* A = anterior nasal spine; B = anterior nasal floor; C = posterior nasal floor; D = anterior cribriform plate; E = posterior cribriform plate; F = sphenoid ostium opening. A–F = 61.50 mm (range, 43–69 mm); B–D = 45.73 mm (range, 38–52 mm); C–E = 44.93 mm (range, 36–52 mm). The ideal swab target for the nasopharyngeal swab is indicated by the yellow star. Source: Lynch PJ, Jaffee CC. Head anatomy with olfactory nerve. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Head_olfactory_nerve.jpg (viewed Oct 2020). Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 (full terms at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/). Original image adapted by Sandeep Mistry.

Box 4 – Illustration of safe nasopharyngeal swab technique following the horizontal plane between the nostril and the external ear canal along the nasal floor

Box 5 – Diagram to illustrate safe angles to swab*

* The blue horizontal line bisects the points between the nasal floor and the external auditory canal. Source: Lynch PJ, Jaffee CC. Head anatomy with olfactory nerve. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Head_olfactory_nerve.jpg (viewed Oct 2020). Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 (full terms at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/). Original image adapted by Sandeep Mistry.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Department of Health. Total COVID‐19 tests conducted and results. Australian Government, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/total-covid-19-tests-conducted-and-results (viewed Sept 2020).

- 2. Sullivan C, Schwalje A, Jensen M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid leak after nasal swab testing for coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA 2020; 146: 1179–81.

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for collecting and handling of clinical specimens for COVID‐19 testing. CDC, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html#collecting (viewed Oct 2020).

- 4. Public Health Laboratory Network. COVID‐19 swab collection: upper respiratory specimen. Canberra: Department of Health, Australian Government, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/06/phln-guidance-covid-19-swab-collection-upper-respiratory-specimen.pdf (viewed Oct 2020).

- 5. Lang J. Clinical anatomy of the nose, nasal cavity, and paranasal sinuses. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1989.

No relevant disclosures.