Patients with serious mental illness who require surgical care are routinely treated in non‐psychiatric hospitals.1 As the prevalence of serious mental illness is relatively low (2–3% in Australia2), it is unsurprising that surgeons only infrequently ask patients about their mental health before operations, and lack confidence in caring for these vulnerable and complex patients.3

Serious mental illness should be treated like any other medical comorbidity and managed pro‐actively, both before and after surgery, to optimise the patient’s care. This ideal is realised for some surgery types, such as solid organ transplantation and bariatric surgery,4,5 but established care pathways for patients undergoing routine surgical treatment are rare. Further, patients with serious mental illnesses have a higher burden of chronic disease,6 experience negative attitudes from a range of health professionals,7,8,9,10,11 and may find navigating complex health systems difficult.12,13

Several studies have investigated surgical outcomes for people with serious mental illness, but there have been few reviews; findings with regard to relative mortality and morbidity have been mixed, and the overall risk for these vulnerable patients is unclear. The aim of our systematic review and meta‐analysis was to develop a greater understanding of the association between having a serious mental illness and outcomes of elective surgery for adults, including in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality, hospital re‐admission, post‐operative complications, and hospital length of stay.

Methods

We employed the methods recommended by the Cochrane Methods Prognosis Group14 and our review protocol concords with the PRISMA‐P statement15 (PROSPERO registration, CRD42018080114; 30 January 2018).

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, and the Cochrane Library for publications in English to 30 July 2018 of studies that examined associations between having a serious mental illness and surgical outcomes in adults who underwent elective surgery; the final search was conducted on 15 August 2018 (online Supporting Information, table 1). Two authors (KM, DS) screened all titles and abstracts and excluded irrelevant publications. Two authors (KM, DS) independently evaluated the full text of potentially eligible articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third reviewer (MS).

Eligibility criteria

We included peer‐reviewed publications in our systematic review if they reported data for patients aged 18 years or more who underwent elective surgery; a pre‐operation measure of serious mental illness; post‐operative outcomes, as defined below; and a measure of association between having a serious mental illness before the operation and post‐operative outcomes, or data that permitted assessment of such an association. Studies solely concerned with delirium, children, emergency surgery, case reports, case series with fewer than ten patients, and qualitative studies were excluded.16

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes assessed were in‐hospital mortality, 30‐day mortality, post‐operative complications, and length of hospital stay. Secondary outcomes were admission to and length of stay in intensive care, blood transfusions, non‐routine discharge, discharge destination, hospital costs, pain, adverse events, and re‐admission within 30 days of discharge.

“Any serious mental illness” was defined as including adjustment disorder, affective disorder, anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, mood disorder, mental retardation, neurotic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, personality disorder, post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), psychosis, schizophrenia, somatisation, substance misuse‐related mental health disorder, and Tourette syndrome.

“Any post‐operative complication” was defined as including anastomotic strictures or failure, anaemia, bleeding or blood transfusion, bowel obstruction, cardiovascular complication, cerebral spinal fluid leak, death, deep wound infection, deep vein thrombosis or venous thrombo‐embolism, diarrhoea, not being discharged from hospital within 30 days of surgery, gastrointestinal complication, ileus, infection, infected seroma, intra‐abdominal abscess, intra‐operative complication, intubation, mechanical wound complication, meningitis, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism or complication, re‐intervention using percutaneous, endoscopic or operative techniques, renal failure, return to theatre, septicaemia, stroke, superficial site infection, surgical site infection, urinary complication, urinary tract infection, wound complications, infections or dehiscence, and “other complications”.

Pain was defined as any measure of pain in hospital or within 30 days of hospital discharge.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (KM, DS) independently collated data from each included review in standardised data extraction forms: sample characteristics (age, sex), specialty type, serious mental illness type and assessment methodology, and primary and secondary outcome measures. Quality of evidence was assessed with the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool.14 Two authors (KM, DS) independently assessed the risk of bias; disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Studies were grouped by serious mental illness and post‐operative outcomes. When possible, a subgroup analysis was based on objective classifications of serious mental illness; ie, International Classification of Diseases, ninth or tenth revisions (ICD‐9 or ICD‐10) codes, or clinical diagnosis.

Meta‐analyses were conducted in Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis, version 3 (Biostat). Odds ratios (ORs) or mean differences (MDs) were calculated (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) in random effects models to provide pooled effect estimates for each analysis. When meta‐analysis was not possible because of data heterogeneity or because the results could not be merged as “any serious mental illness”, the results of the individual studies were described qualitatively.

Results

A total of 3824 publications were identified by the initial database search. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, the full text of 79 articles was assessed for eligibility. Twenty‐six studies17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42 that investigated the association between serious mental illness prior to an operation and post‐operative outcomes were included in our review (Supporting Information, figure 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

The included studies covered a range of surgical specialties: mixed specialties (585 930 patients in total),17,20,22,28,29,31,40 and orthopaedic (5 383 241 patients),18,21,23,27,32,37 colorectal or gastrointestinal (24 801 patients),19,25,26,41 cardiothoracic or vascular (611 patients),34,35,36,37,38 bariatric (21 405 patients),30,33 breast (40 251 patients),24,39 and plastic surgery (116 597 patients);42 a total of 6 129 806 unique patients were included. Study sample sizes ranged between 2134 and 5 339 284 patients.32 The mean age of patients was 54.5 years (standard deviation, 15.0 years); 3 095 939 were men (52%) (each based on 23 articles that reported age and sex).

Serious mental illness was diagnosed with an objective measure (eg, ICD diagnosis codes) or by a psychiatrist in 19 studies; in seven studies, it was determined with a validated patient self‐report instrument. The investigated diagnoses were any serious mental illness,17,41,42 depression,17,39,40 anxiety,17,23,32,35,38,39,41 schizophrenia,22,25,27,29,31,32 bipolar disorder,17,22 and PTSD17,22 (Supporting Information, table 2).

Risk of bias

Overall risk of bias was low in eighteen studies.17,36,37,38,40,41,42 Five studies were assessed as having a moderate risk of bias because of problems with study participation, outcome measurements, confounding, or poor statistical analysis.18,19,23,28,35 Three studies were assessed as having a high risk of overall bias because of problems with study attrition, prognostic measures, confounding, or statistical analysis.27,34,39 Risk of study confounding was low in 20 studies that measured and adjusted for key confounders, such as age, sex, ethnic background, and comorbid medical conditions that can affect surgical outcomes17,18,36,37,38,40,41,42 (Supporting Information, table 3).

Primary outcomes

In‐hospital and 30‐day mortality

Five studies investigated the association between having a serious mental illness and in‐hospital death.17,31,32,35,38 (Supporting Information, figure 2). There was no significant association between having any serious mental illness and in‐hospital mortality (three studies, 42 926 patients; OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.69–2.12),17,31,38 nor statistically significant associations specifically with depression,17,32,35 anxiety,17,32,38 or schizophrenia.31,32 Similarly, no significant associations were found in studies that reported only objective measures for determining serious mental illness (any serious mental illness17,31 or depression17,32).

Eight studies investigated the association between having a serious mental illness and death within 30 days of discharge (Supporting Information, figure 3).17,19,22,25,28,29,37,40 No association was found with having any serious mental illness (six studies, 83 013 patients; OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 0.86–3.99),17,19,25,28,29,37 nor specifically with depression,17,22,37,40 anxiety,17,40 schizophrenia,22,29 bipolar disorder,17,22 or PTSD.17,22 Similarly, no significant associations were found in studies that reported objective measures for determining serious mental illness (any serious mental illness17,19,25,28,29 or depression17,22,40).

Post‐operative complications

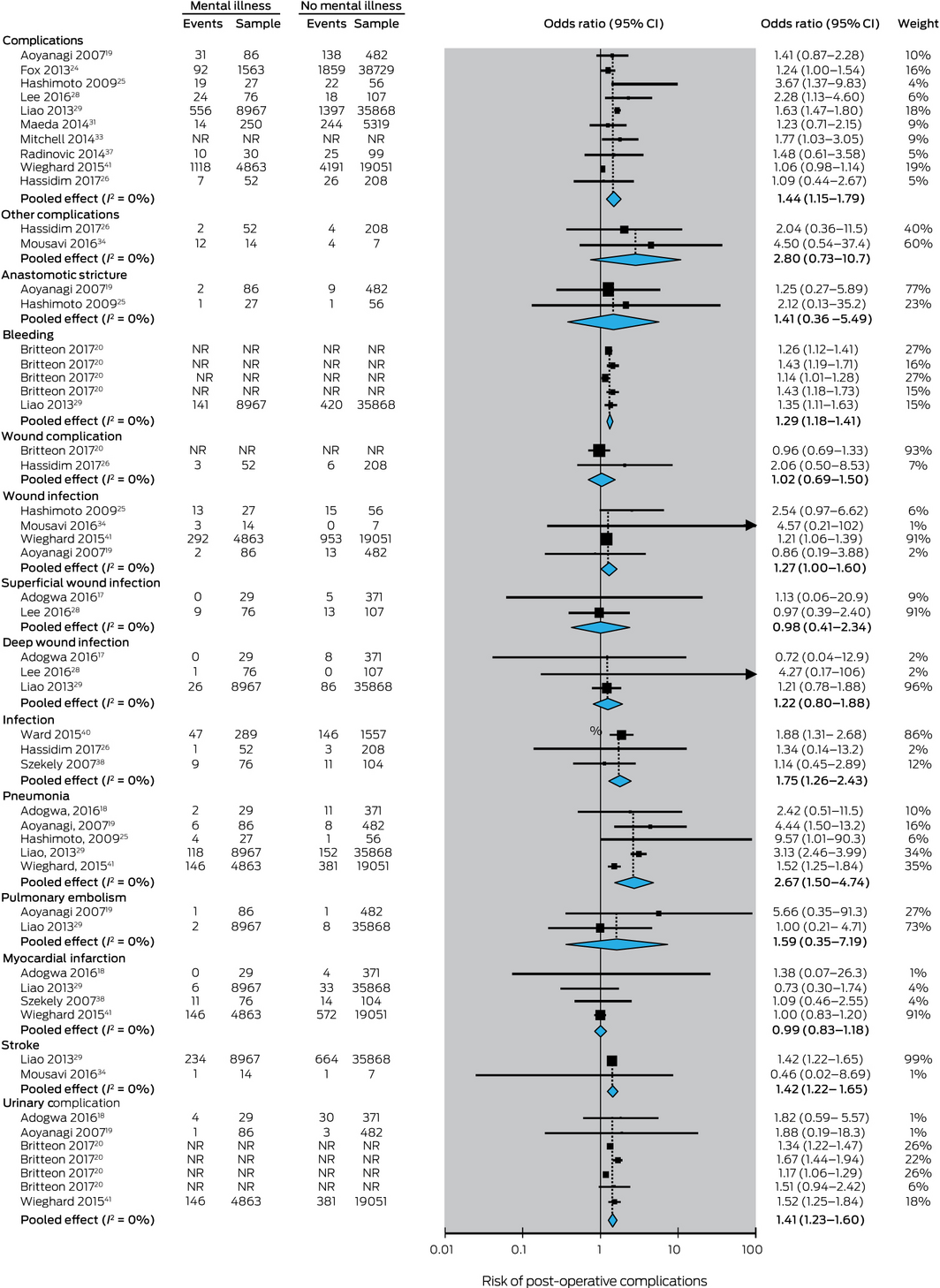

The association between having a serious mental illness and post‐operative complications was investigated in 17 studies,18,19,20,31,32,33,34,37,38,40,41 15 of which we included in our meta‐analysis. The association between having any serious mental illness diagnosis and having any post‐operative complication (ten studies, 125 624 patients) was statistically significant19,41 (pooled effect: OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.15–1.79) (Box 1). Restricting analysis to studies that used objective measures for determining serious mental illness diagnoses (eight studies, 115 704 patients)19,24,25,26,28,29,31,41 yielded a similar result (pooled effect: OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.11–1.79).

Associations between having any serious mental illness and five complications were each statistically significant: bleeding (pooled effect: OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18–1.41),20,29 infection (pooled effect: OR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.26–2.43),26,38,40 pneumonia (pooled effect: OR, 2.67; 95% CI, 1.50–4.74),18,19,25,29,41 stroke (pooled effect: OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.22–1.65),29,34 and urinary complications (pooled effect: OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.23–1.60).18,19,20,41

Two studies that investigated the association between having a serious mental illness and post‐operative complications were not included in our meta‐analysis because of the heterogeneity of the data collected22 or because data were reported by individual diagnosis and could not be combined into “any serious mental illness”.32 One of these studies (321 131 patients) found that post‐operative complications were significantly more frequent among patients with schizophrenia than among patients with bipolar disorder, PTSD, or major depressive disorder.22 The other study (5 339 284 patients) found significantly higher rates of wound complications, pulmonary embolism, and blood transfusion, but not of other complications, in patients with depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia than in patients without these disorders. Patients with schizophrenia had more severe post‐operative complications than patients with depression, anxiety, or no serious mental illness32 (Supporting Information, table 4).

Length of hospital stay

The association between having a serious mental illness and hospital length of stay was investigated in 18 studies,18,36,37,38,39,40,41 ten of which were included in our meta‐analysis (Box 2). The pooled results of these ten studies (5 385 970 patients) indicated that the mean length of hospital stay was significantly greater for patients with any serious mental illness than for patients without such illnesses (pooled effect: MD, 2.6 days; 95% CI, 0.8–4.4 days).18,39 Restricting analysis to studies that included an objective measure for determining the serious mental illness diagnosis18,19,25,26,28,29,32 yielded a similar result (pooled effect: MD, 0.8 days; 95% CI, 0.5–1.2 days)

The mean hospital stay was longer for patients with schizophrenia than for those without schizophrenia (pooled effect: MD, 11.8 days; 95% CI, 4.8–18.7 days)29,32 but differences for patients with depression18,32,37,40 or anxiety32,38,40 were not statistically significant.

Associations between having a serious mental illness and hospital length of stay were also assessed by seven other studies.21,23,24,30,31,35,41 Four studies found patients with serious mental illness stayed significantly longer in hospital, including those with any serious mental illness,24,31 anxiety,23 or depression,36 while three studies found that serious mental illness was not associated with significantly longer hospital length of stay21,30,41 (Supporting Information, table 4).

Secondary outcomes

Intensive care: admission and length of stay

One study (44 835 patients) found that the odds of post‐operative admission to intensive care were significantly higher for patients with schizophrenia than for those without a serious mental illness (OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.54–1.76).29 Another study (180 patients) found no significant difference in the length of intensive care stay for patients with and without anxiety38 (Supporting Information, table 4).

Pain

Three studies compared post‐operative pain in surgical patients with or without serious mental illnesses; the two we included in our meta‐analysis assessed post‐operative pain scores for patients with either anxiety or depression.35,39 Patients with anxiety had significantly higher mean pain scores (pooled effect: MD, 22.0 points; 95% CI, 14.0–29.9 points); those with depression had significantly higher pain scores one day after their operations than patients without depression, as assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; pooled effect: MD, 15.3 points; 95% CI, 3.4–26.6 points) but not with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; pooled effect: MD, 9.4 points; 95% CI, –0.2 to 19.0 points) (Supporting Information, figure 4).

Another study (75 patients) found that post‐operative pain scores for surgical patients with schizophrenia were significantly lower than for a control group two, five and 24 hours and five days after their operations27 (Supporting Information, table 4).

Non‐routine hospital discharge and discharge destination

One large study (5 339 284 patients) found that patients with schizophrenia (OR, 4.30; 95% CI, 4.00–4.60), depression (OR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.30–1.40), or anxiety (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.20–1.20) were each significantly more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility than patients without these conditions.32 Another study (23 890 patients) found that routine discharges were significantly less likely for patients with serious mental illnesses (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83–0.94) and that home health care at discharge was more likely than for those without psychiatric diagnoses (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.06–1.20).41

Hospital costs

Mean in‐hospital costs for patients who had any serious mental illness were found by two American studies to be significantly higher than for patients who did not (pooled effect: MD, $US851; 95% CI, $US8 – $US1693; Supporting Information, figure 5).24,29 Another study (5569 patients), excluded from our meta‐analysis, also reported significantly higher costs for patients who had with psychiatric illnesses31 (Supporting Information, table 4).

Hospital re‐admission

The pooled results of five studies that investigated the association between any serious mental illness and hospital re‐admission within 30 days of discharge18,22,28,30,42 indicated that patients with any serious mental illness were almost twice as likely to be re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days as other patients (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.17–3.10); the difference for patients with depression was not statistically significant18,22 (Supporting Information, figure 6).

Adverse events

A study that investigated the association between serious mental illness and adverse events (83 patients) found that patients with serious mental illness were more likely to be physically restrained (OR, 5.60; 95% CI, 1.87–16.8) and exhibit resistant behaviour after their operation (OR, 11.0; 95% CI, 3.35–36.1) than patients without serious mental illnesses.25

Discussion

We found that several surgical outcomes were more likely for people with serious mental illnesses than for other patients, including greater risk of post‐operative complications, longer stays in hospital, higher inpatient costs, and greater risk of re‐admission within 30 days of discharge. Rates of in‐hospital or 30‐day death were similar for patients with or without serious mental illness, but these events are generally rare (0.08% of all surgical patients).43 Further, our findings suggest that surgical patients with serious mental illness probably stay in hospital longer because of post‐operative complications rather than behavioural disturbances or other confounders linked to their mental illness diagnosis, including medical comorbidity. Given both the small number of studies that reported the secondary surgical outcomes we investigated and their mixed findings, our conclusions regarding the influence of having a serious mental illness on the experience of surgical patients in intensive care, post‐operative pain, behavioural adverse events, and discharge destination were limited. With the exception of pain in patients with schizophrenia, we identified no surgical outcome for which outcomes were better for patients with serious mental illness than for patients without such illnesses.

Our review is the first to include a meta‐analysis of the surgical outcomes we investigated, but a few reviews have examined differences in post‐operative complications and hospital length of stay for surgical patients with serious mental illness. A 2007 systematic review44 included findings from 12 studies of patients who had undergone elective or emergency surgery (including eight by one group of investigators). The frequencies of post‐operative complications and death were higher for patients with schizophrenia (ten studies) and rates of post‐operative delirium were higher for patients with major depressive disorders (two studies) than for patients without these disorders. The review authors could not identify any studies that examined surgical outcomes for patients with other serious mental illness diagnoses.44 A 2005 systematic review45 found that the results of 15 studies of service use by medical and surgical inpatients with mental disorders, including six with surgical cohorts, were mixed; the authors concluded that considering only hospital length of stay was too narrow an approach for assessing resource use. In 2014, a non‐systematic review of the treatment of people with mental disorders in non‐psychiatric hospitals (32 studies) found that post‐operative complications were more frequent and mean hospital stay longer for patients with mental disorders.1

Our findings suggest opportunities for optimising surgical outcomes for patients with serious mental illnesses, including testing a range of interventions, such as pre‐surgery screening tools,46 collaborative care models that enhance communication between and linkage of surgical and mental health teams,47 and improving awareness in inpatient clinical teams of the needs of patients with serious mental illness.48 Associations between post‐operative surgical outcomes and specific serious mental illness diagnoses should also be investigated, including substance misuse and eating disorder diagnoses, data for which are not currently available.

Strengths and limitations of our review

Strengths included our prospective registration of the protocol of our review with the PROSPERO registry, the very large overall sample size (more than 6 million patients), the number and quality of the included studies (risk of bias deemed to be low in 18 of 26 included publications), and our separate analysis of the 19 studies that employed objective measures of serious mental illness and thereby included more comparable data.

Limitations included the heterogeneity of patients grouped according to both surgical specialty and mental illness diagnosis, which did not allow analysis by clinical severity of illness. This problem is related to the broader lack of recognition of differences in the presentation of each mental disorder, and should be taken into consideration when interpreting our results. Although subgroup analyses were performed when possible, the method for determining serious mental illness diagnoses may have influenced our results. Of the 19 studies employing objective measures, ICD codes were retrospectively reviewed in twelve, an approach that underestimates the prevalence of chronic medical conditions, including serious mental illnesses.49 Indeed, ICD codes for mental disorders are only allocated to patients who require treatment or resources related to these disorders during their admission; that is, patients with active illness but not those with stable mental health. Six different tools were used in the seven studies that employed subjective measures for determining diagnoses; although validated for this purpose, each has limitations, including the fact that they capture symptoms but not necessarily clinically defined disorders.36

Conclusion

Our systematic review and meta‐analysis indicate that having a serious mental illness is associated with higher rates of post‐operative complications, longer stays in hospital, higher inpatient costs, and a higher rate of re‐admission within 30 days of discharge, but not with higher in‐hospital or 30‐day mortality.

Received 6 November 2019, accepted 5 January 2021

- Kate E McBride1,2

- Michael J Solomon3

- Paul G Bannon2

- Nicholas Glozier2

- Daniel Steffens3

- 1 Institute of Academic Surgery, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Surgical Outcomes Research Centre, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Mather B, Roche M, Duffield C. Disparities in treatment of people with mental disorder in non‐psychiatric hospitals: a review of the literature. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2014; 28: 80–86.

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Mental health services, in brief 2014 (Cat. no. HSE 154). Canberra: AIHW, 2014. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/1fa38ce8-bed1-47b7-ac3d-5be09baac2cc/16873.pdf.aspx?inline=true (viewed Feb 2019).

- 3. McBride KE, Solomon MJ, Steffens D, et al. Mental illness and surgery: do we care? ANZ J Surg 2019; 89: 630–631.

- 4. Fabricatore AN, Crerand CE, Wadden TA, et al. How do mental health professionals evaluate candidates for bariatric surgery? Survey results. Obes Surg 2006; 16: 567–573.

- 5. Heinrich TW, Marcangelo M. Psychiatric issues in solid organ transplantation. Har Rev Psychiatry 2009; 17: 398–406.

- 6. Morgan W, Jablensky M, McGrath C, et al. People living with psychotic illness 2010. Report on the second Australian national survey. Nov 2011. Archived: https://web.archive.org/web/20201021051954if_/http://www6.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/717137A2F9B9FCC2CA257BF0001C118F/$File/psych10.pdf (viewed Feb 2019).

- 7. Arvaniti A, Samakouri M, Kalamara E, et al. Health service staff’s attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009; 44: 658–665.

- 8. Gabbidon J, Clement S, van Nieuwenhuizen A, et al. Mental Illness: Clinicians’ Attitudes (MICA) scale: psychometric properties of a version for healthcare students and professionals. Psychiatry Res 2013; 206: 81–87.

- 9. Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, et al. Attitudes towards people with a mental disorder: a survey of the Australian public and health professionals. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1999; 33: 77–83.

- 10. Kassam A, Glozier N, Leese M, et al. Development and responsiveness of a scale to measure clinicians’ attitudes to people with mental illness (medical student version). Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010; 122: 153–161.

- 11. van der Kluit MJ, Goossens PJ. Factors influencing attitudes of nurses in general health care toward patients with comorbid mental illness: an integrative literature review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2011; 32: 519–527.

- 12. Lambert TJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Med J Aust 2003; 178 (9 Suppl): S67–S70. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2003/178/9/medical-comorbidity-schizophrenia

- 13. Phelan M, Stradins L, Morrison S. Physical health of people with severe mental illness: can be improved if primary care and mental health professionals pay attention to it. BMJ 2001; 322: 443–444.

- 14. Higgins J, Green S, editors. Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.1.0. Updated Mar 2011. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org (viewed Feb 2021).

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010; 8: 336–341.

- 16. Solomon MJ, McLeod RS. Clinical studies in surgical journals: have we improved? Dis Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 43–48.

- 17. Abrams TE, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on surgical mortality. Arch Surg 2010; 145: 947–953.

- 18. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Mehta AI, et al. Association between baseline affective disorders and 30‐day readmission rates in patients undergoing elective spine surgery. World Neurosurg 2016; 94: 432–436.

- 19. Aoyanagi N, Iizuka I, Watanabe M. Surgery for digestive malignancies in patients with psychiatric disorders. World J Surg 2007; 31: 2323–2328.

- 20. Britteon P, Cullum N, Sutton M. Association between psychological health and wound complications after surgery. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 769–776.

- 21. Chaichana KL, Mukherjee D, Adogwa O, et al. Correlation of preoperative depression and somatic perception scales with postoperative disability and quality of life after lumbar discectomy. J Neurosurg Spine 2011; 14: 261–267.

- 22. Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Sako EY, et al. Serious mental illnesses associated with receipt of surgery in retrospective analysis of patients in the Veterans Health Administration. BMC Surg 2015; 15: 74.

- 23. Floyd H, Sanoufa M, Robinson JS. Anxiety’s impact on length of stay following lumbar spinal surgery. Perm J 2015; 19: 58–60.

- 24. Fox JP, Philip EJ, Gross CP, et al. Associations between mental health and surgical outcomes among women undergoing mastectomy for cancer. Breast J 2013; 19: 276–284.

- 25. Hashimoto N, Isaka N, Ishizawa Y, et al. Surgical management of colorectal cancer in patients with psychiatric disorders. Surg Today 2009; 39: 393–398.

- 26. Hassidim A, Bratman Morag S, Giladi M, et al. Perioperative complications of emergent and elective procedures in psychiatric patients. J Surg Res 2017; 220: 293–299.

- 27. Kudoh A, Ishihara H, Matsuki A. Current perception thresholds and postoperative pain in schizophrenic patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2000; 25: 475–479.

- 28. Lee DS, Marsh L, Garcia-Altieri MA, et al. Active mental illnesses adversely affect surgical outcomes. Am Surgeon 2016; 82: 1238–1243.

- 29. Liao CC, Shen WW, Chang CC, et al. Surgical adverse outcomes in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based study. Ann Surg 2013; 257: 433–438.

- 30. Litz M, Rigby A, Rogers AM, et al. The impact of mental health disorders on 30‐day readmission after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018; 14: 325–331.

- 31. Maeda T, Babazono A, Nishi T, et al. Influence of psychiatric disorders on surgical outcomes and care resource use in Japan. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014; 36: 523–527.

- 32. Menendez ME, Neuhaus V, Bot AGJ, et al. Psychiatric disorders and major spine surgery: epidemiology and perioperative outcomes. Spine 2014; 39: E111–E122.

- 33. Mitchell JE, King WC, Chen JY, et al. Course of depressive symptoms and treatment in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS-2) study. Obesity 2014; 22: 1799–1806.

- 34. Mousavi SH, Sekula RF, Gildengers A, et al. Concomitant depression and anxiety negatively affect pain outcomes in surgically managed young patients with trigeminal neuralgia: long-term clinical outcome. Surg Neurol Int 2016; 7: 98.

- 35. Navarro-García MA, Marín-Fernández B, de Carlos-Alegre V, et al. Preoperative mood disorders in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: risk factors and postoperative morbidity in the intensive care unit. Rev Esp Cardiol (English edition) 2011; 64: 1005–1010.

- 36. Poole L, Leigh E, Kidd T, et al. The combined association of depression and socioeconomic status with length of post‐operative hospital stay following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: data from a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res 2014; 76: 34–40.

- 37. Radinovic KS, Markovic-Denic L, Dubljanin‐Raspopovic E, et al. Effect of the overlap syndrome of depressive symptoms and delirium on outcomes in elderly adults with hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 1640–1648.

- 38. Székely A, Balog P, Benkö E, et al. Anxiety predicts mortality and morbidity after coronary artery and valve surgery: a 4-year follow-up study. Psychosom Med 2007; 69: 625–631.

- 39. Torer N, Nursal TZ, Caliskan K, et al. The effect of the psychological status of breast cancer patients on the short-term clinical outcome after mastectomy. Acta Chir Belg 2010; 110: 467–470.

- 40. Ward N, Roth JS, Lester CC, et al. Anxiolytic medication is an independent risk factor for 30‐day morbidity or mortality after surgery. Surgery 2015; 158: 420–427.

- 41. Wieghard NE, Hart KD, Herzig DO, et al. Psychiatric illness is a disparity in the surgical management of rectal cancer. Ann Surg Onc 2015; 22: 573–579.

- 42. Wimalawansa SM, Fox JP, Johnson RM. The measurable cost of complications for outpatient cosmetic surgery in patients with mental health diagnoses. Aesth Surg J 2014; 34: 306–316.

- 43. Watters DA, Fox JP, Johnson RM. Perioperative mortality rates in Australian public hospitals: the influence of age, gender and urgency. World J Surg 2016; 40: 2591–2597.

- 44. Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Pugh MJ, et al. Postoperative complications in the seriously mentally ill: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 31–38.

- 45. Koopmans GT, Donker MC, Rutten FH. Length of hospital stay and health services use of medical inpatients with comorbid noncognitive mental disorders: a review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2005; 27: 44–56.

- 46. Patel D, Sharpe L, Thewes B, et al. Feasibility of using risk factors to screen for psychological disorder during routine breast care nurse consultations. Cancer Nurs 2010; 33: 19–27.

- 47. Druss BG, Silke A. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006; 28: 145–153.

- 48. Kutney-Lee A, Aiken LH. Effect of nurse staffing and education on the outcomes of surgical patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2008; 59: 1466–1469.

- 49. Bot AG, Menendez ME, Neuhaus V, et al. The influence of psychiatric comorbidity on perioperative outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 519–527.

Abstract

Objective: To assess the association between having a serious mental illness and surgical outcomes for adults, including in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality, post‐operative complications, and hospital length of stay.

Study design: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of publications in English to 30 July 2018 of studies that examined associations between having a serious mental illness and surgical outcomes for adults who underwent elective surgery. Primary outcomes were in‐hospital and 30‐day mortality, post‐operative complications, and length of hospital stay. Risk of bias was assessed with the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool. Studies were grouped by serious mental illness diagnosis and outcome measures. Odds ratios (ORs) or mean differences (MDs), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were calculated in random effects models to provide pooled effect estimates.

Data sources: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, and the Cochrane Library.

Data synthesis: Of the 3824 publications identified by our search, 26 (including 6 129 806 unique patients) were included in our analysis. The associations between having any serious mental illness diagnosis and having any post‐operative complication (ten studies, 125 624 patients; pooled effect: OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.15–1.79) and a longer stay in hospital (ten studies, 5 385 970 patients; MD, 2.6 days; 95% CI, 0.8–4.4 days) were statistically significant, but not those for in‐hospital mortality (three studies, 42 926 patients; OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.69–2.12) or 30‐day mortality (six studies, 83 013 patients; OR, 1.85; 95% CI, 0.86–3.99).

Conclusions: Having a serious mental illness is associated with higher rates of post‐operative complications and longer stays in hospital, but not with higher in‐hospital or 30‐day mortality. Targeted pre‐operative interventions may improve surgical outcomes for these vulnerable patients.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO, CRD42018080114 (prospective).