The known The risk of suicide may be higher for medical practitioners and nurses than for those in other occupations. This problem had not been assessed at a national level or by sex.

The new Age-standardised rates of suicide were higher for female medical practitioners, and for male and female nurses, than for other occupations. The rate of suicide for health professionals with access to prescription medicines was higher than for health professionals without ready access to these means.

The implications Suicide prevention initiatives should focus on workplace factors and differential risks for men and women employed as health professionals.

In general, health professionals are healthier and live longer than the general population.1 However, research has identified elevated rates of suicidal ideation and death by suicide among certain groups of health professionals, including doctors, nurses and dentists.2-4

Suicides by health professionals typically have two distinguishing features. First, they are more likely to involve poisoning5-7 than methods such as hanging, which is more common in the general population.8 Second, women working in health professions appear to be at particular risk; whereas in the general population the rate of suicide for men is nearly four times as high as that for women,8 the rates of suicide among female health professionals are comparable with those of their male peers.2-4 These two findings may be related, as the lethality of self-poisoning increases with access to prescription medicines, and women are more likely than men to choose poisoning as the method of suicide. Other possible explanations for the elevated rates of suicide among female health professionals include greater exposure to work-related stressors.9

Australian research on suicide by health professionals has been restricted to Queensland;6 there are no published analyses at the national level. Further, research has been restricted to studying doctors and nurses, with a notable lack of published data on the burden of suicide in other health care professions in Australia. A better understanding of whether suicide rates are elevated for all health professionals, or for medical professionals specifically, would assist efforts to prevent suicide. We therefore used a national register of occupationally coded suicide cases to determine the rates of suicide by health professionals in Australia and the suicide methods used, and to compare these with data for suicides by people in other occupations. We also assessed whether suicide rates for female health professionals were higher than for their male colleagues.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a nationwide study of deaths by suicide between 2001 and 2012. The study included all employed adults with a known occupation who were at least 20 years old at the time of their death.

Ascertainment of suicide deaths

We identified suicide cases using the National Coronial Information System (NCIS). The NCIS is an internet-based data storage and retrieval system that enables coroners, government agencies, and researchers to monitor external causes of death in Australia and to identify cases for further investigation and analysis. The NCIS provides basic demographic information, as well as employment status and occupation at the time of death as recorded in coronial files.

The quality and completeness of NCIS data vary between cases, particularly for the early years of the scheme (the system was launched in 2000), and suicide may be under-reported because of legislative and professional differences between states and between coroners.10 In addition, there is a significant lag between deaths and their recording in the NCIS caused by the duration of the coronial process, meaning that 2012 was the most recent complete year with full available data for inclusion in our study. Nevertheless, the NCIS offers the best available information on suicide mortality in Australia, and is used as the basis for compiling the official death statistics published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

We classified suicide methods according to the International Classification of Disease, 10th revision (ICD-10), codes X60–X84.11 We were unable to code the method of suicide for 5.4% of cases.

Ascertainment of occupational groups

Our study only included persons employed in a known occupation at the time of death. Occupational information was coded according to the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) to the four digit level.12 Information on the coding procedure we used is included in Appendix 1.

We divided occupations into two broad groups: health professions, and all other occupations. “Health professions” included all health care-related occupations classified by ANZSCO as professions, based on the educational requirements and skills required for the job (ANZSCO codes 25xx and 2723). It did not include health care workers who are classified as community and personal service workers (code 1220), such as paramedics and Indigenous health workers. We analysed data for three health profession groups: medical practitioners (code 253x), midwifery and nursing professionals (code 254x), and other health professions, which included health diagnostic and promotion professions (codes 251x and 252x; such as pharmacists and optometrists), therapy professions (code 252x; such as physiotherapists and occupational therapists), and psychologists (code 2723). The “other occupations” category included all people employed in any other occupation at the time of death.

Ascertainment of population size

We extracted ABS 2006 census data (the midpoint of our study) on the size of the population aged 20–70 years, by age, sex and occupation, using TableBuilder (http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/tablebuilder?opendocument&navpos=240). Age was coded into 10-year bands; ANZSCO codes were used for occupation.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis and age-standardised suicide rates

We report the age and sex of individuals in the four occupational groups: medical practitioners, nurses and midwives, other health professions, and all other occupations. We also report the suicide methods used by members of these groups. Suicide rates per 100 000 person-years were calculated for each of the four groups, stratified by sex. These rates were age-standardised to the Australian standard population (2001),13 restricting the standard population to those aged 20–70 years (the range of ages at death for the analysed health professionals).

Regression models

We compared the rates of suicide for the four occupational groups in negative binomial regression models. We used the “other occupations” group as the reference category, and the model was controlled for year of death, age and sex. We initially tested for effect modification by sex by including an interaction term in the model; as there was strong evidence of effect modification, in this article we report models stratified by sex.

We then assessed the influence of occupational access to prescription medicines by comparing suicide rates among health professionals who have ready access to prescription medicines in the course of their work with those for health professionals who do not. We defined health care professions with access to these lethal means as registered professions whose members are legally allowed to prescribe, supply or administer prescription medicines. This includes doctors, nurses and midwives, dental practitioners and pharmacists (Appendix 1). We did not include optometrists and podiatrists, although some practitioners in these professions are permitted to prescribe certain medicines. We assumed that sex would not be an interacting factor, as male and female health professionals would have the same level of knowledge about and access to prescription medicines.

For all models, coefficients were transformed to incidence rate ratios (IRRs) to aid interpretation. Analysis was undertaken in Stata 13.1 (StataCorp).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, 2015-278) and the Justice Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, CF/15/13534).

Results

We identified 9828 suicides in Australia during the 12-year study period by employed adults aged 20–70 years, including 369 (3.8% of all suicides) by health professionals (Box 1). The age-standardised rate of suicide for male medical practitioners was 14.8 per 100 000 person-years, and 22.7 per 100 000 person-years for male nurses and midwives; the rate for men in other (non-health care) occupations was 14.9 per 100 000 person-years. The age-standardised rate of suicide among female health professionals was 6.4 per 100 000 person-years for medical practitioners, 8.2 per 100 000 person-years for midwives and nurses, and 4.5 per 100 000 person-years for other health professionals; this compares with 2.8 per 100 000 person-years for women in other occupations. Crude suicide rates by occupational group and sex are summarised in Appendix 2.

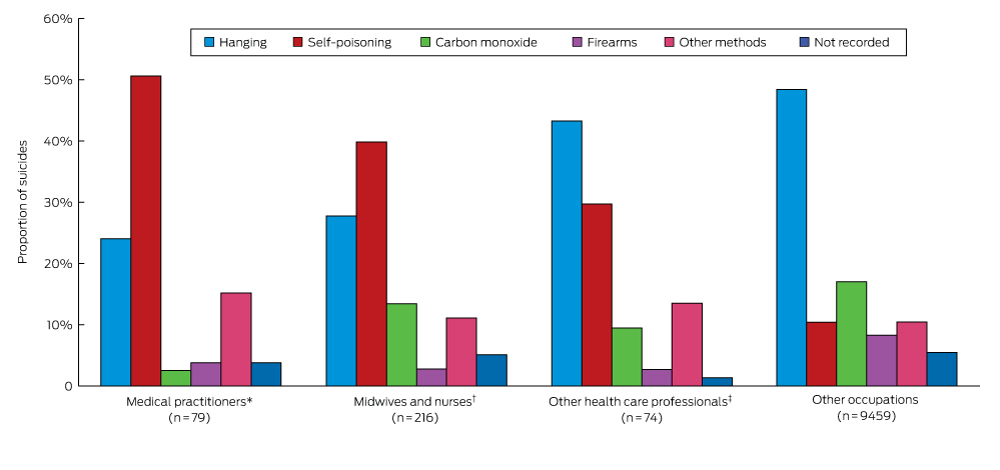

Hanging as the method of suicide was much less common among doctors (24%) and nurses and midwives (28%) than among other health professionals (43%) and those in other occupations (48%) (Box 2). Practitioners in these groups used self-poisoning (doctors, 51%; nurses and midwives, 40%) more often than did members of other occupations (10%).

A significant interaction between sex and occupation with respect to suicide rate was detected (χ2 test, P < 0.001), so models stratified by sex were calculated. After adjusting for year and age, we found a significantly higher suicide rate for men employed as nurses and midwives than for men in occupations other than health professions (IRR, 1.50; P = 0.006) (Box 3). The suicide rate for male “other health professionals” was slightly lower than for men employed in non-health care occupations (IRR, 0.75; P = 0.061). For women, being employed as a doctor (IRR, 2.52; P < 0.001) or as a nurse or midwife (IRR, 2.65; P < 0.001) was associated with significantly higher suicide rates than for women in non-health care occupations.

The rate of suicide among health professionals with ready access to prescription medicines was 1.62 times that for health professionals without this access (P < 0.001) (Box 4).

Discussion

In this national study of suicide in Australia, we found important sex differences between health professionals and other occupational groups in the epidemiology of suicide. The rate of suicide among women employed in any health profession was higher than for women in other occupations; the difference was statistically significant for women employed as nurses or medical practitioners. Compared with that for men in other occupations, the suicide rate was higher only among male health professionals in the fields of nursing and midwifery. Further, the rate of suicide was 62% higher among health professionals with ready access to prescription medicines than among health professionals without such access. Our findings also suggest that suicide rates across the entire working population have decreased slightly over time, and that suicide rates are lower among older working people (those over 50 years of age) than among younger working people (20–39 years of age) (Box 3, Box 4).

Sex-related stressors

Almost 15 years ago, Hawton and colleagues14 speculated that the rate of suicide by female health professionals would decline as more women entered the medical professions. Unfortunately, rates have not declined, despite the increasing number of women in these professions. It has been suggested that women working in male-dominated areas of medicine face a number of barriers that hinder their career advancement.15,16 In addition, female professionals may still feel pressure to undertake child care and household roles, leading to considerable gender role stress. This premise has been supported by studies in which young female doctors reported considerable pressure associated with combining work and family.17

Occupational gender norms may also play a role in explaining the high suicide rate among male nurses and midwives. These occupations are organised to reinforce traditionally feminine behaviours of caring and support. Qualitative research has found that some male nurses experience anxiety about the perceived stigma associated with their non-traditional career choice.18 These anxieties may constitute a risk factor for suicide for men in these occupations.

Work-related stressors

There is strong evidence that doctors experience a considerable number of psychosocial job stresses, including work–family conflict,19 long working hours, high job demands, and the fear of making mistakes at work.20 These psychosocial job stressors have been associated with common mental disorders (anxiety and depression) in several prospective cohort studies.21 Those working in caring professions, including nursing, may be particularly exposed to trauma, and they may also experience it vicariously through contact with patients and their families. Further, many health professionals operate their own businesses and may thus experience the stress of being sole operators.22

Suicide by self-poisoning

We found strong evidence of higher rates of suicide by self-poisoning among health professionals than by people in other occupations. We also found a higher rate of suicide for health professionals with ready access to prescription medicines than for health professionals without such access. These findings are consistent with those of several other studies. For example, a national study based on Danish population registers found differences in the use of medicinal drugs for deliberate fatal overdoses. Compared with teachers, who employed them in 22% of suicides, medicinal drugs were used far more frequently by nurses (55%), doctors (56%) and pharmacists (66%).2 An analysis of the Queensland suicide register found that poisoning was used more often by medical professionals (59% of suicides) and nurses (44%) than by education professionals (24%) and other groups (19%).6 A recent review of nine studies of suicide by nurses concluded that medication poisoning was the predominant method used for taking their own lives.5 Similarly, pharmacists employed poisoning as a suicide method more often than other employed people.7 It thus appears likely that access to prescription medicines as a lethal means is a risk factor in suicide by health professionals.

Limitations of our study

Major strengths of the study include the use of the best available individual-level data on suicide in Australia, the inclusion of multiple health care professions, and coverage of an entire national population over a 12-year period. We note, however, a number of limitations. First, under-reporting of suicide in the NCIS because of misclassification of the cause of death is a problem, as in any official record of deaths.10 Second, our study only included people who were employed at the time of death, so that health professionals who had stopped working because of illness, who were suspended from medical practice or de-registered, or who had retired were not included in our analysis. In addition, occupation may have been miscoded by police when collecting information, or during the coding process, despite independent coding by two researchers and the use of a structured approach to classification. Third, data on the method of suicide is incomplete, as initial data collection from the NCIS did not include this information. We have subsequently obtained these data for most suicides, but were unable to match suicide method for a small proportion of cases. Fourth, we note that the ANZSCO list of health professions is not perfectly aligned with the occupations regulated as health professions under the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme for health practitioners. For example, dental hygienists are a registered health profession, but are not listed as a health profession by ANZSCO; nutrition professionals are not a registered health profession, but are listed as such by ANZSCO.

The suicide rates for men in several of the jobs classified as “other occupations” (the denominator for our risk estimation) were particularly high, including men employed in lower skilled occupations and in technical and trade occupations.23 This circumstance will have affected the results of our analysis, as it will have reduced the calculated IRR when comparing suicide rates in male health professionals with those in other occupations. We did not have sufficient data to analyse suicide rates within specific medical specialties, such as anaesthesia, or within smaller health professions, such as dentistry. We cannot exclude the possibility that men working in these occupations may be at increased risk of suicide. Finally, we acknowledge the different age structures of the population of those in medical professions and of the standard Australian population; those employed in health professions were substantially older.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the rate of suicide among women employed in a range of health professions, including medicine, is markedly higher than that for women in other, non-health care occupations. An understanding of the specific stressors and risk factors experienced by women in these professions may shed additional light on targeted prevention strategies. Attention should also be given to the high rate of suicide among men, including those employed in health care. Strategies targeted at health professionals should also pay heed to the higher rate of suicide among professionals with access to prescription medicines.

Box 1 – Age-standardised rates of suicide by employed adults aged 20–70 years, Australia, 2001–2012, for health professional groups and for all other occupations

|

|

All persons |

Men |

Women |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Medical practitioners |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Number of suicides |

79 |

62 |

17 |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age, years |

44.7 |

46.3 |

39.0 |

||||||||||||

|

Population* |

53 672 |

34 649 |

19 023 |

||||||||||||

|

Adjusted suicide rate† (95% CI) |

12.2 (9.4–15.0) |

14.8 (11.0–18.7) |

6.4 (3.4–9.5) |

||||||||||||

|

Midwives and nurses |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Number of suicides |

216 |

49 |

167 |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age, years |

44.1 |

41.6 |

44.8 |

||||||||||||

|

Population* |

198 961 |

17 710 |

181 251 |

||||||||||||

|

Adjusted suicide rate† (95% CI) |

9.5 (8.0–11.0) |

22.7 (14.8–30.7) |

8.2 (6.7–9.7) |

||||||||||||

|

Other health professionals‡ |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Number of suicides |

74 |

47 |

27 |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age, years |

43.9 |

45.8 |

40.7 |

||||||||||||

|

Population* |

88 633 |

34 800 |

53 833 |

||||||||||||

|

Adjusted suicide rate† (95% CI) |

7.6 (5.7–9.6) |

11.5 (8.0–14.9) |

4.5 (2.3–6.6) |

||||||||||||

|

Other occupations |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Number of suicides |

9459 |

8172 |

1287 |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age, years |

40.3 |

40.4 |

39.6 |

||||||||||||

|

Population* |

8 060 397 |

4 441 462 |

3 618 935 |

||||||||||||

|

Adjusted suicide rate† (95% CI) |

9.6 (9.3–9.8) |

14.9 (14.5–15.2) |

2.8 (2.6–3.0) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006 census data. The data for health professionals exclude non-clinicians. † Age-standardised rate per 100 000 person-years. ‡ Nutrition, medical imaging, occupational and environmental health professionals, optometrists and orthoptists, pharmacists, other health care diagnostic and promotion professionals, chiropractors and osteopaths, complementary health therapists, dental practitioners, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, audiologists and speech pathologists and therapists, psychologists. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Suicide methods used by health professionals and by members of other occupations aged 20–70 years, Australia, 2001–2012

* General practitioners and resident medical officers, anaesthetists, specialist physicians, psychiatrists, surgeons, other medical practitioners. † Midwives, nurse educators and researchers, nurse managers, registered nurses. ‡ Nutrition, medical imaging, occupational and environmental health professionals, optometrists and orthoptists, pharmacists, other health care diagnostic and promotion professionals, chiropractors and osteopaths, complementary health therapists, dental practitioners, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, audiologists and speech pathologists and therapists, psychologists.

Box 3 – Negative binomial regression model comparing suicide rates for health professionals with rates for members of other occupations aged 20–70-years, Australia, 2001–2012, stratified by sex

|

|

Suicides |

Population* |

Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Men |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Medical practitioners |

62 |

34 649 |

1.01 (0.78–1.31) |

0.929 |

|||||||||||

|

Midwives and nurses |

49 |

17 710 |

1.50 (1.12–2.01) |

0.006 |

|||||||||||

|

Other health professionals† |

47 |

34 800 |

0.75 (0.56–1.01) |

0.061 |

|||||||||||

|

Other occupations (reference) |

8172 |

4 441 462 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Age‡ |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

60–70 years |

531 |

379 933 |

0.75 (0.64–0.88) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

50–59 years |

1406 |

917 291 |

0.82 (0.71–0.95) |

0.007 |

|||||||||||

|

40–49 years |

2344 |

1 146 076 |

1.07 (0.94–1.23) |

0.295 |

|||||||||||

|

20–39 years (reference) |

4049 |

2 085 321 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Year (as continuous variable)§ |

8330 |

4 528 621 |

0.98 (0.97–1.00) |

0.017 |

|||||||||||

|

Women |

|

|

|

— |

|||||||||||

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Medical practitioners |

17 |

19 023 |

2.52 (1.55–4.09) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Midwives and nurses |

167 |

181 251 |

2.65 (2.22–3.15) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Other health professionals† |

27 |

53 833 |

1.41 (0.96–2.08) |

0.083 |

|||||||||||

|

Other occupations (reference) |

1287 |

3 618 935 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Age‡ |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

60–70 years |

65 |

216 119 |

0.74 (0.56–0.97) |

0.030 |

|||||||||||

|

50–59 years |

287 |

775 659 |

0.90 (0.76–1.06) |

0.200 |

|||||||||||

|

40–49 years |

406 |

1 042 075 |

0.94 (0.80–1.10) |

0.439 |

|||||||||||

|

20–39 years (reference) |

740 |

1 839 189 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Year (as continuous variable)§ |

1498 |

3 873 042 |

0.96 (0.95–0.98) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006 census data. The data for health professionals exclude non-clinicians. † Nutrition, medical imaging, occupational and environmental health professionals, optometrists and orthoptists, pharmacists, other health care diagnostic and promotion professionals, chiropractors and osteopaths, complementary health therapists, dental practitioners, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, audiologists and speech pathologists and therapists, psychologists. ‡ All occupations. § *Incidence rate ratio refers to the effect of a one-year increase in time on the suicide rate. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Negative binomial regression model of suicide rate, comparing suicide rate for health professionals with access to prescription medicines with that for members of all other occupations aged 20–70-years, Australia 2001–2012

|

|

Suicides |

Population* |

Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Health professionals without access to lethal means (reference) |

55 |

64 365 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Health professional with access to lethal means† |

314 |

276 091 |

1.62 (1.20–2.17) |

0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Other occupations |

9459 |

8 060 397 |

0.98 (0.75–1.29) |

0.887 |

|||||||||||

|

Age‡ |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

60–70 years |

596 |

596 052 |

0.76 (0.66–0.88) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

50–59 years |

1693 |

1 692 950 |

0.86 (0.76–0.97) |

0.013 |

|||||||||||

|

40–49 years |

2750 |

2 188 151 |

1.03 (0.92–1.16) |

0.571 |

|||||||||||

|

20–39 years (reference) |

4789 |

3 924 510 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Sex‡ |

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

Women |

1498 |

3 873 042 |

0.22 (0.20–0.25) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

Men (reference) |

8330 |

4 528 621 |

1 |

— |

|||||||||||

|

Year§ |

9828 |

8 401 663 |

0.98 (0.96–0.99) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006 census data. The data for health professionals exclude non-clinicians. † Pharmacists, dental practitioners, generalist medical practitioners, anaesthetists, internal medicine specialists, psychiatrists, surgeons, other medical practitioners, midwives, nurses. ‡ All occupations. § Incidence rate ratio refers to the effect of a one-year increase in time on the suicide rate. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 15 September 2015, accepted 1 March 2016

- Allison J Milner1,2

- Humaira Maheen1

- Marie M Bismark3

- Matthew J Spittal4

- 1 Centre for Population Health Research, Deakin University, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Centre for Health Equity, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Centre for Health Policy, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 Centre for Mental Health, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

This work was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (SRG-1-091-13), the Society for Mental Health Research, and Deakin University. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design or in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Allison Milner receives financial support from the Society for Mental Health Research, Deakin University, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

- 1. Frank E, Biola H, Burnett CA. Mortality rates and causes among US physicians. Am J Prev Med 2000; 19: 155-159.

- 2. Hawton K, Agerbo E, Simkin S, et al. Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: a national study based on Danish case population-based registers. J Affect Disord 2011; 134: 320-326.

- 3. Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 2295-2302.

- 4. Lindeman S, Laara E, Hakko H, Lonnqvist J. A systematic review on gender-specific suicide mortality in medical doctors. Br J Psychiatry 1996; 168: 274-279.

- 5. Alderson M, Parent-Rocheleau X, Mishara B. Critical review on suicide among nurses. Crisis 2015; 36: 91-101.

- 6. Kolves K, De Leo D. Suicide in medical doctors and nurses: an analysis of the Queensland Suicide Register. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013; 201: 987-990.

- 7. Skegg K, Firth H, Gray A, Cox B. Suicide by occupation: does access to means increase the risk? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010; 44: 429-434.

- 8. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3303.0. Causes of death, Australia, 2013 [website]. Mar 2015. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/3303.0∼2013∼Main%20Features∼Suicides∼10004 (accessed Jan 2016).

- 9. Escribà-Agüir V, Martin-Baena D, Pérez-Hoyos S. Psychosocial work environment and burnout among emergency medical and nursing staff. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2006; 80: 127-133.

- 10. De Leo D, Dudley MJ, Aebersold CJ, et al. Achieving standardised reporting of suicide in Australia: rationale and program for change. Med J Aust 2010; 192: 452-456. <MJA full text>

- 11. World Health Organization. Intentional self-harm (X60–X84). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision (ICD-10) — WHO version for 2015 [website]. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en#/X60-X84 (accessed Dec 2015).

- 12. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1220.0. ANZSCO: Australian and New Zealand standard classification of occupations, 2013, version 1.2 [website]. June 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1220.02013,%20Version%201.2?OpenDocument (accessed Dec 2015).

- 13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Standard population for use in age-standardisation. June 2013. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/log?openagent&31010do003_201212.xls&3101.0&Data%20Cubes&67380BDD03ED7082CA257B8F00126E17&0&Dec%202012&20.06.2013&Latest (accessed Dec 2015).

- 14. Hawton K, Clements A, Sakarovitch C, et al. Suicide in doctors: a study of risk according to gender, seniority and specialty in medical practitioners in England and Wales, 1979–1995. Epidemiol Community Health 2001; 55: 296-300.

- 15. Boulis AK, Jacobs JA. The changing face of medicine: women doctors and the evolution of health care in America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008.

- 16. Riska E. Towards gender balance: but will women physicians have an impact on medicine? Soc Sci Med 2001; 52: 179-187.

- 17. Alexandros-Stamatios GA, Marilyn JD, Cary LC. Occupational stress, job satisfaction and health state in male and female junior hospital doctors in Greece. J Manage Psychol 2003; 18: 592-621.

- 18. Simpson R. Masculinity at work: the experiences of men in female dominated occupations. Work Employ Soc 2004; 18: 349-368.

- 19. Goehring C, Bouvier Gallacchi M, Künzi B, Bovier P. Psychosocial and professional characteristics of burnout in Swiss primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional survey. Swiss Med Wkly 2005; 135: 101-108.

- 20. beyondblue. National mental health survey of doctors and medical students. Oct 2013. https://www.beyondblue.org.au/docs/default-source/research-project-files/bl1132-report---nmhdmss-full-report_web.pdf?sfvrsn=4 (accessed Aug 2015).

- 21. Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bruinvels D, Frings-Dresen M. Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup Med 2010; 60: 277-286.

- 22. Cocker F, Martin A, Scott J, et al. Psychological distress, related work attendance, and productivity loss in small-to-medium enterprise owner/managers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013; 10: 5062-5082.

- 23. Milner A, Niven H, LaMontagne AD. Occupational class differences in suicide: evidence of changes over time and during the global financial crisis in Australia. BMC Psychiatry 2015; 15: 223.

Abstract

Objectives: To report age-standardised rates and methods of suicide by health professionals, and to compare these with suicide rates for other occupations.

Study design: Retrospective mortality study.

Setting, participants: All intentional self-harm cases recorded by the National Coronial Information System during the period 2001–2012 were initially included. Cases were excluded if the person was unemployed at the time of death, if their employment status was unknown or occupational information was missing, or if they were under 20 years of age at the time of death. Suicide rates were calculated using Australian Bureau of Statistics population-level data from the 2006 census.

Main outcome measures: Suicide rates and method of suicide by occupational group.

Results: Suicide rates for female health professionals were higher than for women in other occupations (medical practitioners: incidence rate ratio [IRR], 2.52; 95% CI, 1.55–4.09; P < 0.001; nurses and midwives: IRR, 2.65; 95% CI, 2.22–3.15; P < 0.001). Suicide rates for male medical practitioners were not significantly higher than for other occupations, but the suicide rate for male nurses and midwives was significantly higher than for men working outside the health professions (IRR, 1.50; 95% CI 1.12–2.01; P = 0.006). The suicide rate for health professionals with ready access to prescription medications was higher than for those in health professions without such access or in non-health professional occupations. The most frequent method of suicide used by health professionals was self-poisoning.

Conclusion: Our results indicate the need for targeted prevention of suicide by health professionals.