Implementing the roadmap to close the gap for vision — progress and more work to do

The roadmap to close the gap for vision was developed after extensive nationwide consultation and launched in 2012.1 It comprises 42 recommendations that span a whole-of-system approach to eliminate disparities in Indigenous eye health.2 These recommendations seek to increase accessibility and uptake of eye care services by Indigenous Australians; improve coordination between eye care providers, primary care and hospital services; improve awareness of eye health among patients and clinicians; and ensure culturally appropriate health services. The roadmap is a costed and sector-endorsed framework for a sustainable and efficient system. Community engagement is fundamental for achieving these objectives. It is essential that community and sector stakeholders drive and genuinely own this effort. This public health initiative includes activities to be implemented at regional, jurisdictional and national levels in order to achieve health system reform and improve patient engagement across the eye care pathway.

The roadmap aims at more than just improving eye health — it is about achieving equity. Up to 94% of vision loss in Indigenous adults is avoidable or amenable to treatment.2 Additionally, vision influences and is influenced by the social determinants of health. The child who can see the blackboard and the adult who can drive and participate in gainful employment have opportunities to improve their circumstances; social factors such as educational attainment and employment have a profound impact on a range of health outcomes. Vision also affects independence in activities of daily living, including self- and family care, and the ability to administer medication and manage other health issues. Finally, vision loss accounts for 11% of the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians,3 so it follows that fixing the eye care system to address avoidable vision loss will help to close the broader health and social gaps and will have flow-on effects well beyond eye health.

After decades of relative political inertia and a policy approach that has delivered periodic but short-lived activity,4 the roadmap has garnered considerable political and stakeholder support. Elements of the roadmap are currently being progressed nationally in several jurisdictions and in a number of health regions.

In this article, we report on the progress made in the 3 years since the launch of the roadmap, and call for support for these efforts from the broader medical and public health communities.

Regional activity

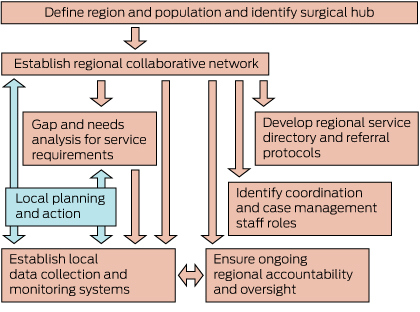

The roadmap identifies specific activities required at the regional level (Box 1). Regions take into account state or territory health department, Medicare Local and other boundaries, but should include a cataract surgical facility. Regional implementation requires the establishment of a collaborative network to coordinate and oversee regional activities. This group of key local stakeholders includes Aboriginal health services; the local hospital district; the Medicare Local; primary care; optometry and ophthalmology clinicians; and public health authorities. Regional implementation is iterative, requiring regular measurement of system performance and adoption of any necessary activity to bridge identified service delivery gaps.

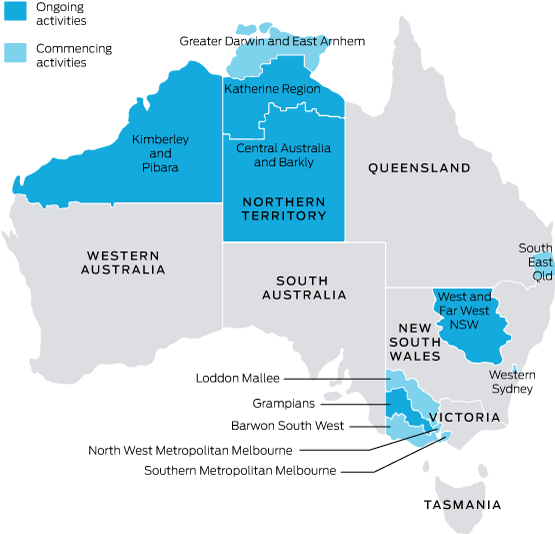

To date, 12 regions have initiated this process (Box 2). They cover five jurisdictions and about 35% of Indigenous Australia. Regions are at different stages of implementation, and the factors influencing the assembly and composition of the collaborative networks have varied markedly, reflecting differences in local contextual factors and funding arrangements. A dedicated individual has been assigned to an eye health regional implementation role in some regions, either through specific additional funding or reassignment of existing staff resources. These individuals have often had a significant impact.

Regional implementation tools have been developed.5 These include an online calculator that provides first-order estimates of the expected burden of eye disease and associated need for eye care in a region; an eye care service directory template to be populated with local details; specification of regional data requirements for gap analysis and monitoring; and an implementation checklist to guide regional efforts.

The national program for trachoma control has had impressive results, with the prevalence in children reducing from 14% in 2009 to 4% in 2013.6

Expert technical advice and support spanning ophthalmology, optometry, health services management and public health are also available to regions through the Indigenous Eye Health Unit (IEHU) at the University of Melbourne. The IEHU maintains close communications with all regions and receives some federal Department of Health funding for this. The IEHU participates in national forums and regional collaborative network meetings as requested and facilitates the sharing of lessons learned and stakeholder networking between regions.

Jurisdictional and national activity

A number of roadmap recommendations have been fully implemented (Box 3) and we highlight some achievements and ongoing activities.

Governance

A national oversight function, reporting to high levels of government, is essential to govern the roadmap approach. The need for such national leadership and commitment to reducing disparities in Indigenous eye health has recently been noted in speeches in both the Senate and House of Representatives. A national oversight proposal has been presented to government and the appropriate ministerial/advisory forum to assume this function is currently being assessed.

Jurisdictional oversight varies across the country. In Victoria, an eye health committee sits within Koolin Balit, the Victorian Government strategic plan for Aboriginal health. Chaired by the state health department, this committee has broad membership including state and Commonwealth departmental authorities, clinicians and representatives of Indigenous health and eye health peak bodies. Elsewhere, such jurisdictional activity is less well developed, although a similar committee has been established recently in the Northern Territory, sitting within the Aboriginal health planning framework.

Eye health indicators and regular measurement of population eye health status

Regular monitoring of system performance is required at regional, jurisdictional and national levels, and parameters measured and reported need to be consistent across the country and over time. A series of indicators has been developed and recommended for periodic collection and collation at various levels of the health care system. These measures will ascertain the size of any service gaps, inform the nature of any action required to bridge disparities and measure impact over time.

Regular reporting on population-level eye health status is also required. After a 30-year deficit in national population-level eye health data, the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey was conducted in 2008 and its findings highlighted the gross inequities in the burden of avoidable visual impairment and blindness among Indigenous adults.7 National data are needed every 5 years to monitor progress and meet Australia's international commitment to regularly monitor disease burden and reduce prevalence of avoidable blindness under World Health Assembly resolution 66.4.8 The Australian Government has recently committed funding for a National Eye Health Survey, to assess the eye health of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This survey will update the data on vision loss, gauge the collective impact of roadmap activities and help inform future priority action areas.

Eliminating cost as a barrier to accessing eye care

To eliminate cost as a barrier to service uptake, the importance of cost-certainty and bulk-billing have been highlighted for clinicians.9 Approaches to health authorities have sought to reduce consulting fees charged above schedule and to ensure adequate public ophthalmology services.

Cost is also a potential barrier to accessing glasses. Criteria for nationally consistent subsidised spectacle schemes have been endorsed by eye care and Aboriginal peak bodies. Currently, availability, eligibility to access subsidies and out-of-pocket expense vary greatly between jurisdictions.10 Indigenous patients in Victoria can obtain subsidised spectacles at an out-of-pocket cost of $10. In other states, there is limited supply of free glasses under subsidy schemes. Advocacy continues for appropriate low-cost spectacle schemes in each jurisdiction.

Building eye health workforce capacity and coordination of care

Measures to increase workforce capacity, sustainability and resources include increased Commonwealth funding for visiting services, equipment and infrastructure; earmarked funding for ophthalmology training in outback services; and a Medicare item number for retinal photography to increase coverage of retinal screening for people with diabetes.

Recommendations for medical software packages include prompts for providers for annual eye examinations when an Indigenous patient with diabetes presents for care.

Commonwealth funds for visiting optometry and ophthalmology services will be allocated through jurisdictional fundholders from 2015. Significant efforts to improve funding arrangements, and for fundholders to improve the coordination of visiting services, will ensure the appropriate sequencing, frequency and mix of services.

Conclusion

Over the 3 years since the launch of the roadmap to close the gap for vision, progress has been made to increase services, improve efficiencies and support better Indigenous patient engagement with the eye care system. Demonstrable gains are being made and there is growing momentum around the roadmap initiatives, but much remains to be done, and increased government support is required. In partnership with Indigenous communities and organisations, the public health and medical communities have a responsibility to engage with this effort and help close the gap for vision. The template used for eye care has high relevance for integrating care between primary health and essentially all visiting specialist services. With concerted multisectoral effort, political will and a commitment to establishing a sustainable eye care system, the gross disparities in eye health that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians can be eliminated. Equity in vision in Australia may well be in sight.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Taylor HR, Anjou MD, Boudville AI, McNeil RJ. The roadmap to close the gap for vision. Full report. Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit, Melbourne School of Population Health, University of Melbourne, 2012. http://iehu.unimelb.edu.au/?a=538656 (accessed Dec 2014).

- 2. Taylor HR, Boudville AI, Anjou MD. The roadmap to close the gap for vision. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 613-615. <MJA full text>

- 3. Vos T, Taylor HR. Contribution of vision loss to the Indigenous health gap. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2013; 41: 309-310.

- 4. Jones JN, Henderson G, Poroch N, et al. A critical history of Indigenous eye health policy-making: towards effective system reform. Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit, Melbourne School of Population Health, University of Melbourne, 2011. http://iehu.unimelb.edu.au/?a=459851 (accessed Dec 2014).

- 5. Indigenous Eye Health Unit. Roadmap resources. http://iehu.unimelb.edu.au/roadmap/resources (accessed Jun 2015).

- 6. National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit. Australian Trachoma Surveillance Report 2012. Sydney: National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit, The Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales, 2013. http://kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/hiv/resources/Australian%20Trachoma%20Surveillance%20Report%202012.pdf (accessed Dec 2014).

- 7. Taylor HR, Xie J, Fox S, et al. The prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous Australians: the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. Med J Aust 2010; 192: 312-318. <MJA full text>

- 8. Sixty-sixth World Health Assembly. WHA66.4 Towards universal eye health: a global action plan 2014–2019. Geneva: WHO, 2013.

- 9. Taylor HR. Ophthalmolgists and cost uncertainty. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 2014; 42: 904-905.

- 10. Anjou MD, Boudville AI, Taylor HR. Nationally consistent spectacle supply for Indigenous Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health 2013; 37: 94-95.

We acknowledge the ongoing work and contributions of national, jurisdictional and regional stakeholders and staff of the IEHU in advancing the activities of the roadmap.

No relevant disclosures.