“Contributing lives, thriving communities”: the National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services offers clear advice

At the halfway point of its first term, the Abbott Government has finally released the 700-page report of the National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services, Contributing lives, thriving communities.1 Fulfilling a 2013 election commitment, Health Minister Dutton had requested the National Mental Health Commission (NMHC) to recommend specific actions that the federal government could take to directly improve the lives of those affected by mental health problems, as well as to enhance programs for preventing suicide. The terms of reference of the review were restricted to considering how existing resources could be better deployed rather than making requests for new funding.

The NMHC recruited experts to inform its recommendations, and received more than 2000 submissions. It recognised that the Commonwealth already spends $9.6 billion on mental health each year, largely through five direct health or welfare programs (most notably, the disability support pension), but found that our “patchwork of services, programmes and systems … are not maximising the best outcomes from either a social or economic perspective” (page 13).1

The report also concluded that “by far the biggest inefficiencies in the system come from doing the wrong things — from providing acute and crisis response services when prevention and early intervention services would have reduced the need for those expensive services, maintained people in the community with their families and enabled more people to participate in employment and education” (page 14).1

The key recommendations: transforming the system

Allan Fels AO, Chair of the NMHC, and David Butt, NMHC Chief Executive Officer, in their preface to the report of the National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services wrote an open letter to the Minister for Health, Sussan Ley, dated 30 November 2014:

This report gives you clear guidance on practical solutions for change … there is an extraordinarily high degree of consensus as to the directions needed … You will find … immediate priorities for action, a programme to start implementation now and a set of measures to guide change.1

The NMHC report highlights the need to adopt three higher-order principles if genuine system change is to be achieved:

- a person-centred approach to mental health care;

- a new, population-based system architecture; and

- a shift in funding to “upstream” services and support (ie, population health, prevention, early intervention, recovery and participation).

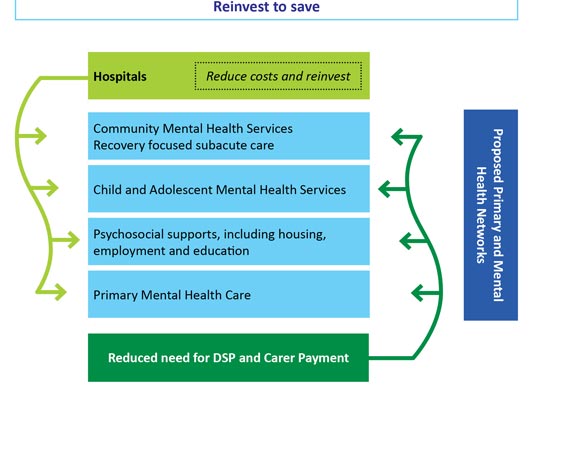

From a funding perspective, the NMHC therefore highlighted the need for the federal government to redirect its new investments, and any savings achieved through increased efficiencies in prevention and early intervention activities, to four key areas:

- community mental health and subacute care;

- child and adolescent mental health services;

- psychosocial support; and

- primary mental health care (Box 1).

Its 25 specific recommendations for transformational change over the next 2 years are grouped into nine key domains. Those that are most important and require immediate action (Box 2) are consistent with recommendations that have previously been proposed by experts in the field.2

From a health care perspective, five key recommendations were made. These emphasised:

- enhanced options for self-care;

- a central role for general practitioners and organised primary care hubs;

- increased and more equitable access to the Medicare Benefits Schedule Better Access initiative;

- direct engagement of pharmacists in the mental health team; and

- greater use of mental health nurses and other allied mental health staff (Box 3).

Plan nationally — act locally

These specific health care responses were framed in the conviction that mental health and suicide prevention activities need to be highly localised in their delivery as well as fundamentally coordinated at the regional level. The philosophy underpinning the primary reporting function of the NMHC is that it is essential to continuously evaluate and compare the differential health and social outcomes across the major geographic and functional regions of Australia. The goal is to use regional (and international) comparisons of meaningful data (eg, suicide attempts, access to care, stable housing and employment rates among those with major mental health disorders) as a stimulus to promote local best practice and to support calls for changes to major national programs.

Consistent with this approach, the NMHC took the innovative step in its 2013 National Report Card of reporting suicide levels at the regional level to emphasise the great variability across urban, regional and rural Australia.3 Previous Australian data have also indicated that lack of access to care is a major predictor of increased suicide rates.4,5 This approach also encourages the detailed examination of national datasets to determine whether major national programs are being delivered equitably — or whether they instead perpetuate inequalities associated with demographic (eg, lack of services for both young and older persons) or geographic factors (eg, rural and regional areas), or socioeconomic status (eg, lack of access to Medicare-supported psychological and psychiatric services6).

In advancing its recommendations, the NMHC has therefore placed great emphasis on the crucial need for local coordination between the new primary health networks (and specifically expanding their mandate to focus on mental health services7), state-based acute care and community services, and psychosocial support and accommodation services (which are largely supplied by non-government agencies, often operating under contract to the federal government). The NMHC report firmly asserts the necessity of local decision-making about the utility of relevant federal government-funded programs, and that the development of coordinated pathways of care between the various local and regional service providers is essential.

At the individual practice level, the NMHC strongly favours the “medical homes” model for those with long-term mental and comorbid physical illnesses.8,9 This would shift the focus of integrated medical and mental health care from the current patchwork of state-based community health and emergency services and Medicare-based private psychology and psychiatry services to an upgraded primary care model. Such collaborative models have the most secure evidence base of all proposed system reforms for enhancing the quality of care for those with mental health and substance misuse problems.10

The government response — thus far

In response to the leaking of the NMHC report in April, the Minister for Health and Minister for Sport, Sussan Ley, immediately ruled out one key recommendation — namely, a quite conservative attempt to rebalance the future use of federal funds by shifting the emphasis from acute public hospital facilities to supporting community-based services. She also announced her intention to establish a new Council of Australian Governments (COAG) working party to work cooperatively with the states and territories, and a new expert reference group to focus on four key areas (suicide prevention; prevention of and early intervention in mental illness; primary care; and national leadership, including regional service integration).11 No clear timeline for specific action on the recommendations of the NMHC report has been announced.

For those of us who have been engaged with mental health reform for some decades, it is worth remembering the official response to the release of the 2005 report of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission and the Mental Health Council of Australia (Not for service: experiences of injustice and despair in mental health care in Australia).12 Prime Minister John Howard immediately joined with NSW Premier Morris Iemma to launch the 2006–2011 COAG national reform package. Throughout that period, the federal government undertook major direct action to improve mental health care, including extending Medicare-based funding for psychological services (the Better Access initiative) and establishing headspace (Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation) to facilitate new primary care-based mental health services for young people.13-15 This engagement was continued by the Gillard Government in its 2011–12 federal Budget, which supported further expansion of early psychosis services, the “Partners in Recovery” program to enable local coordination of health and non-government services, and the establishment of the NMHC to monitor the implementation of these initiatives.16

While there is a strong expectation at this point that the federal government will continue to seek to work with the states to facilitate local service delivery and support suicide prevention initiatives, the responsibility for clear and immediate action in 2015–2016 now clearly lies at the feet of the Abbott Government. We look forward to specific decisions the government is prepared to take in response to the NMHC recommendations and a timeline for the actual delivery of better mental health care, social services and suicide prevention programs.

2 Achieving genuine system change: nine key domains for action, and some specific recommendations for the next 2 years

1. Set clear roles and accountabilities to shape a person-centred mental health system | |

Recommendation 1 | Agree the Commonwealth's role in mental health is through national leadership and regional integration, including integrated primary and mental health care |

2. Agree and implement national targets and local organisational performance measures | |

Recommendation 4 | Adopt a small number of important, ambitious and achievable national targets to guide policy decisions and directions in mental health and suicide prevention. |

3. Shift funding priorities from hospitals and income support to community and primary health care services | |

Recommendation 7 | Reallocate a minimum of $1 billion in Commonwealth acute hospital funding in the forward estimates over the five years from 2017–18 into more community-based psychosocial, primary and community mental health services. |

Recommendation 8 | Extend the scope of Primary Health Networks (renamed Primary and Mental Health Networks) as the key regional architecture for equitable planning and purchasing of mental health programmes, services and integrated care pathways. |

5. Promote the wellbeing and mental health of the Australian community, beginning with a healthy start to life | |

6. Expand dedicated mental health and social and emotional wellbeing teams for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people | |

Recommendation 18 | Establish mental health and social and emotional wellbeing teams in Indigenous Primary Health Care Organisations (including Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services), linked to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specialist mental health services. |

7. Reduce suicides and suicide attempts by 50 per cent over the next decade | |

Recommendation 19 | Establish 12 regions across Australia as the first wave for nationwide introduction of sustainable, comprehensive, whole-of-community approaches to suicide prevention. |

8. Build workforce and research capacity to support systems change | |

Recommendation 20 | Improve research capacity and impact by doubling the share of existing and future allocations of research funding for mental health over the next five years, with a priority on supporting strategic research that responds to policy directions and community needs. |

9. Improve access to services and support through innovative technologies | |

Recommendation 24 | Improve emergency access to the right telephone and internet-based forms of crisis support and link crisis support services to ongoing online and offline forms of information/ education, monitoring and clinical intervention. |

Recommendation 25 | Implement cost-effective second and third generation e-mental health solutions that build sustained self-help, link to biometric monitoring and provide direct clinical support strategies or enhance the effectiveness of local services. |

Source: Contributing lives, thriving communities, pages 10–11.1

3 Five key recommendations for improved mental health care in Australia

4. Empower and support self-care and implement a new model of stepped care across Australia | |

Recommendation 11 | Promote easy access to self-help options to help people, their families and communities to support themselves and each other, and improve ease of navigation for stepping through the mental health system. |

Recommendation 12 | Strengthen the central role of GPs in mental health care through incentives for use of evidence-based practice guidelines, changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule and staged implementation of Medical Homes for Mental Health. |

Recommendation 13 | Enhance access to the Better Access programme for those who need it most through changed eligibility and payment arrangements and a more equitable geographical distribution of psychological services. |

Recommendation 14 | Introduce incentives to include pharmacists as key members of the mental health care team. |

8. Build workforce and research capacity to support systems change | |

Recommendation 21 | Improve supply, productivity and access for mental health nurses and the mental health peer workforce. |

Source: Contributing lives, thriving communities, pages 10–11.1

Provenance: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

- 1. National Mental Health Commission. Contributing lives, thriving communities. Report of the National Review of Mental Health Programmes and Services. Volume 1. Sydney: NMHC, 2014. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media/119905/Vol%201%20-%20Main%20Paper%20-%20Final.pdf (accessed May 2015).

- 2. Hickie IB, McGorry PD, Davenport TA, et al. Getting mental health reform back on track: a leadership challenge for the new Australian Government. Med J Aust 2014; 200: 445-458. <MJA full text>

- 3. A contributing life: the 2013 National Report Card on mental health and suicide prevention. Sydney: National Mental Health Commission, 2013. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/media/94321/Report_Card_2013_full.pdf (accessed Apr 2015).

- 4. Hall WD, Mant A, Mitchell PB, et al. Association between antidepressant prescribing and suicide in Australia, 1991–2000: trend analysis. BMJ 2003; 326: 1008.

- 5. Page AN, Swannell S, Martin G, et al. Sociodemographic correlates of antidepressant utilisation in Australia. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 479-483. <MJA full text>

- 6. Meadows GN, Enticott JC, Inder B, et al. Better access to mental health care and the failure of the Medicare principle of universality. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 190-194. <MJA full text>

- 7. Ley S (Minister for Health). New Primary Health Networks to deliver better local care [media release] 11 Apr 2015. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2015-ley036.htm (accessed Apr 2015).

- 8. The Commonwealth Fund (US). Medical homes [website]. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/topics/current-issues/medical-homes (accessed Apr 2015).

- 9. Edwards ST, Bitton A, Hong J, Landon BE. Patient-centered medical home initiatives expanded in 2009–13: providers, patients, and payment incentives increased. Health Affairs 2014; 33: 1823-1831. Summary: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/in-the-literature/2014/oct/patient-centered-medical-home-initiatives-expanded (accessed Apr 2015).

- 10. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2006.

- 11. Ley S (Minister for Health). Abbott Government plans national approach on Mental Health [media release] 16 April 2015. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/health-mediarel-yr2015-ley039.htm (accessed Apr 2015).

- 12. Mental Health Council of Australia, Brain and Mind Research Institute, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Not for service. Experiences of injustice and despair in mental health care in Australia. Canberra: MHCA, 2005. http://www.hreoc.gov.au/disability_rights/notforservice/summary/index.html (accessed Apr 2015).

- 13. McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R, et al. headspace: Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation — where young minds come first. Med J Aust 2007; 187: S68-S70. <MJA full text>

- 14. Scott EM, Hermens DF, Glozier N, et al. Targeted primary care-based mental health services for young Australians. Med J Aust 2012; 196: 136-140. <MJA full text>

- 15. Cross SPM, Hermens DF, Hickie IB. Treatment patterns and short-term outcomes in an early intervention youth mental health service. Early Interv Psychiatry 2014; doi: 10.1111/eip.12191.

- 16. Commonwealth of Australia. Delivering better hospitals, mental health and health services (Budget 2011–12). May 2011. http://budget.gov.au/2011-12/content/glossy/health/download/glossy_health.pdf (accessed May 2015).

Ian Hickie has been a Commissioner in Australia's National Mental Health Commission since 2012. He was a director of headspace — Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation until January 2012.