Striking disparities in heart failure incidence and outcomes warrant urgent attention

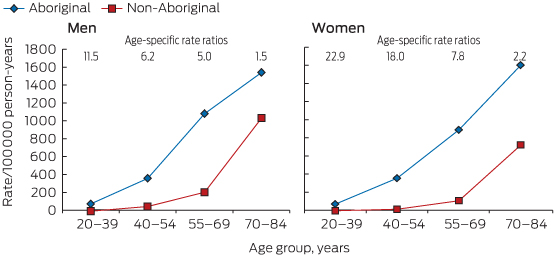

Heart failure (HF), a common sequel of many cardiovascular diseases and predisposing risk exposures, remains a major health problem despite recent advances in medical therapy.1 HF in Aboriginal Australians is characterised by a substantial and distressingly familiar excess in incidence (Box),2 morbidity and mortality, particularly at younger ages.2-4

Strategies to enhance the prevention and early detection of heart failure

The primary prevention of HF in Aboriginal people is paramount and must occur concomitantly with treatment efforts. This requires population-based approaches to address underpinning social determinants of health5 (eg, poverty, marginalisation, environmental factors); cardiovascular risk factor reduction (smoking, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia); increased physical activity; and early detection and management of structural heart disease. Prevention must include multisectoral strategies to address the structural–systemic factors that undermine Aboriginal people's opportunities throughout life. Additionally, screening, monitoring and treatment of HF antecedents in the community setting are needed to reduce HF incidence further, with suitably trained Aboriginal people central to delivering culturally appropriate health education. Further, primary care health professionals should be trained to detect subclinical HF using echocardiography6 and to manage predisposing risk factors optimally.

National guidelines highlight the importance of best-practice management for secondary prevention of HF comprising accessible, multidisciplinary, evidence-based and patient-centred care to improve HF outcomes.1,7 Yet the management of HF in practice remains problematic, with poor continuity of care and fragmented service provision, particularly for Aboriginal people. Rehospitalisation with HF is common, with the majority of readmissions triggered by potentially modifiable factors like poor discharge planning, inadequate competency for self-management and non-adherence to medications and diet, exacerbated by delays in medical consultation for escalating symptoms.8 Shortcomings are amplified for Aboriginal patients, who have additional challenges from increased HF severity; comorbidities; socioeconomic, language and cultural barriers; reduced access to cardiac rehabilitation; and limited access in rural and remote areas.1,2,4-6 A more coordinated but flexible, patient-focused approach that takes into account the complex patient journey of Aboriginal patients, particularly those from rural areas,9,10 is required to enhance chronic HF care for Aboriginal Australians.

Strategies to improve the management and outcomes in patients with clinical heart failure

Although the evidence for successful programs to manage HF and other chronic diseases in Aboriginal Australians is currently inadequate, several studies are underway that will provide a better evidence base to guide this.10-12 While engaging Aboriginal people throughout, implementation of the following actions should occur now, with refinement as new evidence emerges.

- Provide all Aboriginal patients hospitalised with HF, regardless of where they live, with a coordinated, seamless, patient-centred pathway of care. This requires clear clinical protocols and support using Indigenous care coordinators and health workers.

- Enhance the Aboriginal cultural competency of organisations and service providers.

- Strengthen primary health care services and Aboriginal voices within service delivery through engagement of communities.

- Integrate service and program delivery between mainstream services and Aboriginal community-controlled primary health care services, encouraging robust and effective partnerships.

- Recruit Aboriginal champions to create greater awareness of HF and its risk factors.

- Encourage Aboriginal people to enter health careers and enhance support to health professionals in rural and remote areas to address inadequate staffing and workforce turnover.

- Improve health literacy and HF management by providing culturally appropriate information on HF prevention and treatment to the Aboriginal community and individual caregivers.13

- Ensure effective clinical information systems (eg, patient medical records, recall systems) and protocols for information flow and sharing to improve hospital discharge planning, transition to community with appropriate support that includes Aboriginal care coordinators, and ongoing specialist oversight.

- Use technology to overcome geographical challenges, enhancing the use of telemedicine and remote monitoring to improve access to enable specialist input.14

- Use modern and appropriate technology for reminders of follow-up visits and medications.

- Develop and support comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programs (incorporating education, psychosocial support, exercise training, optimal pharmacotherapy) with ongoing case management.10,15

- Ensure sufficient discharge medications to cover patients' return home and next review; and involve community pharmacists and health workers for reminders and checks.

- Change or enhance traditional models of care to incorporate family-based and outreach programs, taking into account clinical, logistical and cultural complexity.9,10

- Facilitate the involvement of Aboriginal people in research and education.

Systematic delivery of multidisciplinary, patient-centred care for Aboriginal Australians with HF is crucial for improving health outcomes, especially for those living in rural and remote areas. This requires rethinking traditional models of care delivery. Importantly, we must ensure that Aboriginal Australians with HF experience satisfactory quality of life and are engaged with their family in end-of-life care decisions. Much progress has occurred with injection of new funds through the Closing the Gap initiatives. Commitment to long-term strategies is critical.

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. National Heart Foundation of Australia. A systematic approach to chronic heart failure care: a consensus statement. Melbourne: National Heart Foundation of Australia, 2013. http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/HF_CHF_consensus_web_FINAL_SP.pdf (accessed Dec 2014).

- 2. Teng TH, Katzenellenbogen JM, Thompson SC, et al. Incidence of first heart failure hospitalisation and outcomes in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal patients in Western Australia, 2000-2009. Int J Cardiol 2014; 173: 110-117.

- 3. Woods JA, Katzenellenbogen JM, Davidson PM, Thompson SC. Heart failure among Indigenous Australians: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2012; 12: 99.

- 4. Teng THK, Katzenellenbogen JM, Geelhoed E, et al. Readmissions after first heart failure hospitalization in Aboriginal versus non-Aboriginal patients in Western Australia, 2000-2007. Global Heart 2014; 9 (1 Suppl): e57-e58. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.1412.

- 5. Brown AD, Morrissey MJ, Sherwood JM. Uncovering the determinants of cardiovascular disease among Indigenous people. Ethn Health 2006; 11: 191-210.

- 6. Page K, Marwick TH, Lee R, et al. A systematic approach to chronic heart failure care: a consensus statement. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 146-150. <MJA full text>

- 7. Michalsen A, König G, Thimme W. Preventable causative factors leading to hospital admission with decompensated heart failure. Heart 1998; 80: 437-441.

- 8. McGrady M, Krum H, Carrington MJ, et al. Heart failure, ventricular dysfunction and risk factor prevalence in Australian Aboriginal peoples: the Heart of the Heart Study. Heart 2012; 98: 1562-1567.

- 9. Dwyer J, Kelly J, Willis E, et al. Managing two worlds together: city hospital care for country Aboriginal people – project report. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute, 2011. http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/fms/sites/health_care_management/mtwt/documents/Project%20Report_WEB.pdf (accessed Dec 2014).

- 10. Iyngkaran P, Harris M, Ilton M, et al. Implementing guideline based heart failure care in the Northern Territory: challenges and solutions. Heart Lung Circ 2014; 23: 391-406.

- 11. Huffman MD, Galloway JM. Cardiovascular health in indigenous communities: successful programs. Heart Lung Circ 2010; 19: 351-360.

- 12. Iyngkaran P, Majoni V, Nadarajan K, et al. AUStralian Indigenous Chronic Disease Optimisation Study (AUSI-CDS) prospective observational cohort study to determine if an established chronic disease health care model can be used to deliver better heart failure care among remote Indigenous Australians: proof of concept – study rationale and protocol. Heart Lung Circ 2013; 22: 930-939.

- 13. National Heart Foundation of Australia. Living every day with my heart failure. Canberra: NHF, 2011. http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/Living-every-day-with-my-heart-failure.pdf (accessed Dec 2014).

- 14. Mooi JK, Whop LJ, Valery PC, Sabesan SS. Teleoncology for indigenous patients: the responses of patients and health workers. Aust J Rural Health 2012; 20: 265-269.

- 15. Hayman NE, Wenitong M, Zangger JA, Hall EM. Strengthening cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Med J Aust 2006; 184: 485-486. <MJA full text>

No relevant disclosures