Internationally, there is a groundswell of activity seeking to identify and reduce the use of health care interventions that deliver marginal benefit, be it through overuse, misuse or waste. England’s National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) began this work in 2005,1 and most recently, the Choosing Wisely campaign led by physician groups in the United States is attracting worldwide attention.2 Other countries, and individual jurisdictions within countries, are also considering the best approaches to reducing the use of low-value health care practices. One problem has been fairness and transparency in identifying and prioritising suboptimal health care practices for consideration. Here, we report on Australian activities; in particular, on a collaborative project aiming to identify existing health care interventions that might warrant analysis from a health technology reassessment and practice optimisation perspective.

Australia’s Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) — a cornerstone of the Australian universal health care system — lists the rebates that are payable to patients for private medical services provided on a fee-for-service basis, and describes these services. In 2012, the MBS contains almost 6000 items (not including pharmaceuticals); only around 3% of these (accounting for about 1% of total MBS expenditure) have been formally assessed against contemporary evidence of safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.3

In the 2009–10 Budget, the Australian Government announced funding over 2 years for a range of projects to develop and implement a new evidence-based MBS Quality Framework — subsequently named the Comprehensive Management Framework for the MBS (CMF)3 — for managing the MBS into the future. The CMF set out to establish new listing, fee-setting and review mechanisms to ensure that prospective and already listed items: (i) meet agreed standards for effectiveness and safety; (ii) are likely to lead to improved health outcomes for patients; and (iii) represent value for money. The CMF is consistent with international efforts to maximise health outcomes and efficiency. CMF reform sought to improve transparency and provide a stronger evidence base for services listed on the MBS. Box 1 lists the key elements and principles of the framework.

A universal challenge in this area is to establish a systematic and transparent strategy to identify potential “low-value” clinical services for review.4-7 Traditional literature search strategies for “unsafe or ineffective care” offer limited utility in isolation.4 In this report, we describe one CMF project that used a range of information sources to identify items for review through an expanded “environmental scanning” approach. The 2-year CMF timeline dictated an expedited process. This work was developed and undertaken over 8 months in the financial year 2010–11.

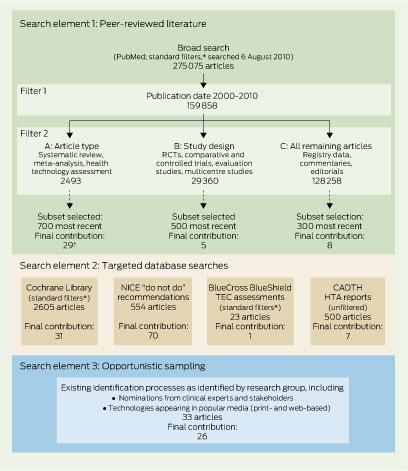

Peer-reviewed literature search: a detailed search strategy was applied to the PubMed search platform (Box 2).

Targeted database search: these were conducted of the Cochrane Library, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) “do not do” recommendations,8 BlueCross BlueShield Association Technology Evaluation Center assessments9 and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) health technology assessments.10

We used a series of keyword and medical subject heading (MeSH) strings (Box 2) across the bibliographic databases to identify potential candidate services for prioritisation. Exclusion criteria were applied to screens of titles, abstracts and full texts of retrieved articles (Box 3), with further limits and filters applied as shown in Box 4. Subsets of results from Filters 2A (Level I evidence11), 2B (Level II evidence11) and 2C (remaining literature search) were selected based on their date of publication, with the most recently published studies (2000–2010) forming the subsets (Box 4). Additionally, we undertook relative oversampling from Filter 2A in consultation with representatives from the Department of Health and Ageing, based on the assumption that the higher level of evidence represented in the results would provide greater yield for the final list of services.

All reports from the Cochrane Library and BlueCross BlueShield Association Technology Evaluation Center assessments were considered, after standard filters (humans, English language, not pharmaceuticals) were applied. All available reports from the NICE “do not do” recommendations and CADTH health technology assessments were considered for inclusion on the master list. These databases offer targeted and specific findings. NICE, for example, teamed with the Cochrane Collaboration to focus their search within Cochrane Reviews and guidelines.1 This complemented our broader method, but when mapped against existing MBS items, numerous services were filtered out as not relevant to the Australian funding context.

After the exclusion criteria (Box 3) were applied to titles, the abstract or executive summary of each included study was obtained and screened. Studies that reported the value of a medical service as inferior or similar to placebo were included, while studies that reported no difference between a service and an active comparator were excluded (because identifying the inferior service from such studies would likely require additional clinical expertise). Articles were screened by the authors of this report, with disagreements resolved through open discussion.

Eligible services were then tracked across search methods to triangulate medical service identification. This enabled us to identify services that appeared across the multiple elements of the search strategy. Triangulation may have value in prioritising further work, along with other criteria that we developed previously.4 This entire process was completed over 8 months by a two-member full-time-equivalent workforce.

A total of 5209 articles were screened for eligibility, resulting in 156 potentially ineffective or unsafe services being flagged for consideration (Appendix). The list includes examples where practice optimisation (ie, comparing the relative value of one treatment option against others) might be required. The Appendix details all the services we identified, including any citations that drew attention to their status as potential candidates, and an extract from the article highlighting key issues relevant to the service. Box 5 lists the 13 services identified by more than one search method; three services were identified by all three methods. While this serves to highlight the crossover points of the search strategies we used, there are other factors related to the candidate services that may influence their relative priority in any assessment process (eg, predominant safety concerns, strong evidence, high volume, cost-effective alternative, etc).4

For groups pursuing a health technology reassessment agenda, the next steps in the process requires further prioritisation of candidate services to a shortlist of those that may go on to formal review. Numerous methods have been proposed for this, each being somewhat context-specific.4-7 The assessment type that offers the greatest efficiency needs to be decided on. For example, initial rapid reviews as opposed to full health technology assessments may offer an efficient means of generating value of information to enhance the prioritisation process.

We also acknowledge that there are challenges in reducing or removing candidate services that are confirmed as having low value. Existing technologies or practices have complexities that do not beset those that are new or emerging, mostly because of their established status in medicine and society. These challenges have been discussed elsewhere.12-19

1 Key elements and principles of the Comprehensive Management Framework for the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)

Introducing a time-limited listing for new MBS items that do not undergo an assessment through the Medical Services Advisory Committee

Requiring an evaluation process for all time-limited items at the end of the time-limited period and before items can be approved for long-term MBS listing, as well as evaluation of amendments made to MBS items

Strengthening arrangements for appropriately setting fees for new MBS services

Establishing systematic MBS monitoring and review processes to inform appropriate amendment or removal of existing MBS items

Processes will focus on using evidence to support best outcomes for patients

Processes will be timely, transparent and offer opportunity for stakeholder participation

Conflicts of interest will be addressed and actively managed

Continuous improvement techniques will be applied, and feedback mechanisms will be embedded in processes to foster a quality-improvement culture

Principles to guide MBS reviews

Reviews have a primary focus on improving health outcomes and the financial sustainability of the MBS, by considering potential:

patient safety risk

limited health benefit

inappropriate use (underuse or overuse) and/or

intentional misuse of MBS services

Reviews are evidence-based, fit-for-purpose and consider all relevant data sources

Reviews are conducted in consultation with key stakeholders including, but not limited to, the medical profession and consumers

Review topics are made public, with identified opportunities for public submissions and outcomes of reviews are published

Reviews are independent of government financing decisions and may result in recommendations representing costs or savings to the MBS, as appropriate, based on the evidence

Secondary investment strategies to facilitate evidence-based changes in clinical practice are considered

Review activity represents efficient use of government resources

Source: Medical Benefits Reviews Task Group. Development of a quality framework for the Medicare Benefits Schedule discussion paper.3

3 Exclusion criteria applied in screening articles

4 Search process

CADTH = Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. HTA = health technology assessment. NICE = National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. RCT = randomised controlled trial. TEC = Technology Evaluation Center. * Standard filters: humans, English, not pharmaceuticals. † Final contribution to list (Appendix) after filtering and mapping evidence for relevance and applicability to existing Medicare Benefits Schedule items; the final list consists of health care services identified by more than one strategy (Box 5).

5 Services identified by more than one search method

Radiotherapy for patients with metastatic spinal cord disease |

|||||||||||||||

* Denotes services identified by all three search elements. † C-reactive protein tests for community-acquired pneumonia from two sources, for urinary tract infections in children in a third. Refer to Appendix for evidence and context (eg, specified indications) for each item. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 10 July 2012, accepted 21 September 2012

- Adam G Elshaug1,2,3

- Amber M Watt2

- Linda Mundy2

- Cameron D Willis2,4

- 1 Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass, USA.

- 2 School of Population Health, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA.

- 3 The Commonwealth Fund, New York, NY, USA.

- 4 Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Evaluation, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Funding for this project was provided by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. The findings and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the Commonwealth Fund, including its directors, officers or staff, or those of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Adam Elshaug and Cameron Willis hold NHMRC Fellowships (627061 and 1013165, respectively). We are grateful to Amy Lambart and Kelly Cameron of the Department of Health and Ageing for their thoughtful guidance and insight throughout the design and subsequent implementation of this project.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Garner S, Littlejohns P. Disinvestment from low value clinical interventions: NICEly done? BMJ 2011; 343: d4519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4519.

- 2. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA 2012; 307: 1801-1802.

- 3. Medical Benefits Reviews Task Group. Development of a quality framework for the Medicare Benefits Schedule. Discussion paper. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, 2010. http://www.health. gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/C38EFE94C3035988CA257713001DA46C/$File/Development%20of%20a%20Quality%20Framework%20for%20the%20MBS%20-%20Discussion%20Paper.pdf (accessed Sep 2012).

- 4. Elshaug AG, Moss JR, Littlejohns P, et al. Identifying existing health care services that do not provide value for money. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 269-273. <MJA full text>

- 5. Ruano Raviña A, Velasco González M, Varela Lema L, et al. Identification, prioritisation and assessment of obsolete health technologies. A methodological guideline. Santiago de Compostela: Galician Health Technology Assessment Agency, 2009.

- 6. Ibargoyen-Roteta N, Gutiérrez-Ibarluzea I, Asua J. Guiding the process of health technology disinvestment. Health Policy 2010; 98: 218-226.

- 7. Nuti S, Vainieri M, Bonini A. Disinvestment for re-allocation: a process to identify priorities in healthcare. Health Policy 2010; 95: 137-143.

- 8. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. NICE “do not do” recommendations. London: NICE, 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/usingguidance/donotdorecommendations/index.jsp (accessed Sep 2012).

- 9. Blue Cross Blue Shield Association. Technology evaluation center assessments. http://www.bcbs.com/blueresources/tec/tec-assessments.html (accessed Sep 2012).

- 10. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Health technology assessment. Ottawa: CADTH, 2012. http://cadth.ca/en/products/health-technology-assessment (accessed Sep 2012).

- 11. National Health and Medical Research Council. A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Appendix B. Canberra: NHMRC, AusInfo, 1999. http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/cp30.pdf (accessed Oct 2012).

- 12. Elshaug AG, Hiller JE, Tunis SR, Moss JR. Challenges in Australian policy processes for disinvestment from existing, ineffective health care practices. Aust New Zealand Health Policy 2007; 4: 23.

- 13. Cotter D. The National Center For Health Care Technology: lessons learned. Health Affairs Blog 2009; 22 Jan. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2009/01/22/the-national-center-for-health-care-technology-lessons-learned/ (accessed Sep 2012).

- 14. Sheingold S, Sheingold BH. Medical technology and the US healthcare system: is this the road to Abilene? World Med Health Policy 2010; 2: Article 5.

- 15. Wirtz V, Cribb A, Barber N. Reimbursement decisions in health policy – extending our understanding of the elements of decision-making. Health Policy 2005; 73: 330-338.

- 16. Donaldson C, Bate A, Mitton C, et al. Rational disinvestment. QJM 2010; 103: 801-807.

- 17. Hodgetts K, Elshaug AG, Hiller JE. What counts and how to count it: physicians’ constructions of evidence in a disinvestment context. Soc Sci Med 2012; Aug 27 [Epub ahead of print].

- 18. Watt AM, Willis CD, Hodgetts K, et al. Engaging clinicians in evidence-based disinvestment: role and perceptions of evidence. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2012; 28: 211-219.

- 19. Henshall C, Schuller T, Mardhani-Bayne L. Using health technology assessment to support optimal use of technologies in current practice: the challenge of “disinvestment”. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2012; 28: 203-210.

Abstract

Objective: To develop and apply a novel method for scanning a range of sources to identify existing health care services (excluding pharmaceuticals) that have questionable benefit, and produce a list of services that warrant further investigation.

Design and setting: A multiplatform approach to identifying services listed on the Australian Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS; fee-for-service) that comprised: (i) a broad search of peer-reviewed literature on the PubMed search platform; (ii) a targeted analysis of databases such as the Cochrane Library and National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) “do not do” recommendations; and (iii) opportunistic sampling, drawing on our previous and ongoing work in this area, and including nominations from clinical and non-clinical stakeholder groups.

Main outcome measures: Non-pharmaceutical, MBS-listed health care services that were flagged as potentially unsafe, ineffective or otherwise inappropriately applied.

Results: A total of 5209 articles were screened for eligibility, resulting in 156 potentially ineffective and/or unsafe services being identified for consideration. The list includes examples where practice optimisation (ie, assessing relative value of a service against comparators) might be required.

Conclusion: The list of health care services produced provides a launchpad for expert clinical detailing. Exploring the dimensions of how, and under what circumstances, the appropriateness of certain services has fallen into question, will allow prioritisation within health technology reassessment initiatives.