It is well established that when “Indigenous people become the researchers and not merely the researched, the activity of research is transformed”.1 But what happens when the researched actively seek to transform the system of research itself?

The Murru Minya project originated from the lead researcher's observations of the significant disparities between community conversations about their experiences of research and the narratives by researchers in academic literature. This raised questions about the conduct and application of ethical research practices in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research. Murru (path) Minya (explain) is Wiradjuri language expressing a direct, true or straight way to explain this path we are on now, what is in the past to explain the path for the future.

We assert that there are clear distinctions between “ethics”, “ethical practice”, and “ethical processes”, and that these terms should not be used interchangeably. It is therefore pertinent to first explain our definitions of these key terms. Ethics broadly refers to a standard set of values and principles that guide our understanding of what is right and wrong. Ethical practice is concerned with how these standards and principles are implemented by researchers and their institutions through their behaviours, policies, and decision making processes. Ethical processes are the relative administrative duties required to be adhered to when seeking institutional ethical review and approval of research. These processes have been developed by Western‐Eurocentric institutions and embedded in their systems to attempt to ensure that ethical research practice is upheld. This mechanism has limited accountability, monitoring, and reporting, making it difficult to ascertain whether ethical review and approval processes have resulted in the true application of ethical practices by researchers working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Accordingly, it is vital to examine and evaluate the effectiveness of these frameworks and systems for and by Aboriginal and Torres Islander people.

This editorial was written by Michelle Kennedy, Wiradjuri woman, lead researcher and tobacco resistance expert, and Felicity Collis, Gomeroi woman and PhD Candidate, both currently working in the university and community‐controlled research sector.

We do not assert that the Murru Minya project2 is the first to explore ethical research principles, values, and guidelines in the context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research. Rather, we recognise the leadership of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities in the development, implementation, consultation, and revision of ethical research practice guidelines and frameworks.3,4,5,6 The work by those before us has produced foundational knowledge to interrogate and critically examine how the system of health and medical research operates under the pretence of protection for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities through the application of currently accepted ethical processes and practices.

In this editorial, we uphold, privilege, and centre our ethical research practices by sharing the development, implementation, and knowledge translation process of Murru Minya. We do not aim to replicate the content of the supplement or forthcoming articles, but rather provide an overview of this comprehensive and extensive Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐led and ‐governed research project. This work does not endorse existing operating systems of research that often perpetuate colonial agendas and silence Indigenous voices. It instead reinforces our sovereignty and self‐determination in knowledge production and emphasises the criticality of creating frameworks that genuinely reflect and respect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspectives and practices.

Explorations of this nature must be collective. In the early stages of the COVID‐19 pandemic (early 2020), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers at various career stages and fields of research — including clinical practice, genomics, data linkage, epidemiology, qualitative research, implementation science, and Indigenous methodologies — collaborated to develop the research question and methodological approach of the Murru Minya project. At the time, one Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander researcher was located in each state and territory to support respectful national implementation of the research project (during implementation several researchers moved institutions). The team actively built upon the knowledge about ethical research generated by Lovett and Wenitong during their 2013 review of ethics guidelines7,8 and developed a funding application for the National Health and Medical Research Council Ideas Grant scheme. This funding application highlighted the significant investment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research by the Australian government, and the potential harm to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities if research is not conducted ethically. Iterative cycles of developing the research proposal laid the foundation for the partnership and research project presented in this supplement.

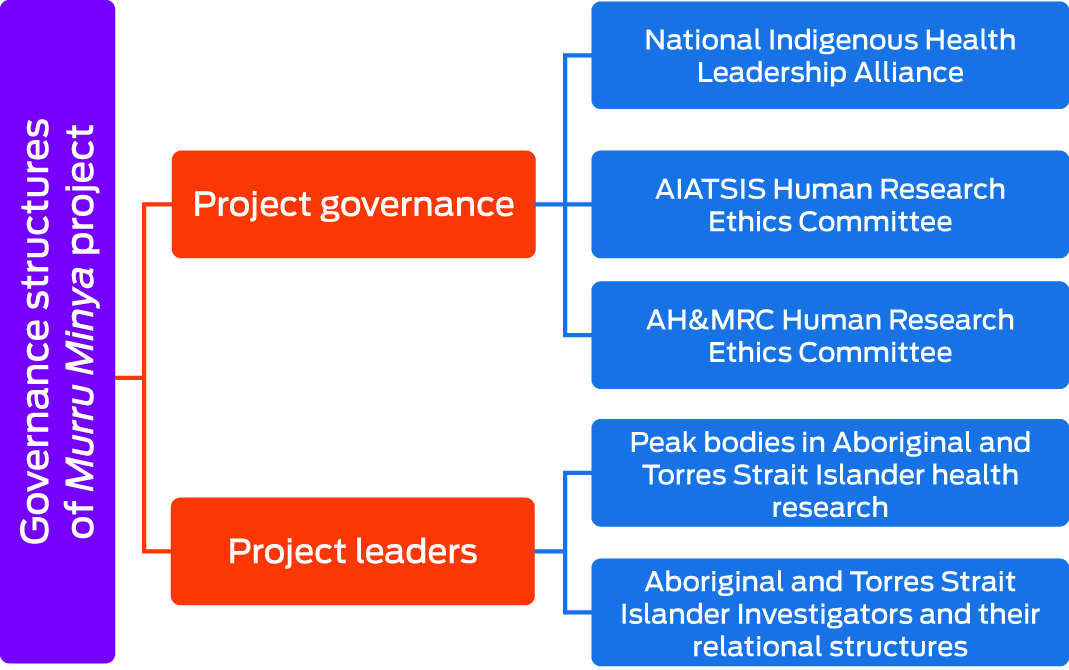

The project was awarded funding in 2021, and a 12‐month national consultation process commenced. This included consulting with key bodies in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled health and Aboriginal Health Human Research Ethics Committees. Support for and guidance of refining the project design, methods, and implementation were provided both formally and informally, based on organisational processes. The consultation process also informed recommendations for the appropriate governing body for this project, moving beyond the academy and ensuring relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peak bodies were actively involved in guiding the work, the National Indigenous Health Leadership Alliance (formerly: the National Health Leadership Forum) (Box 1).

Consultation also resulted in an expansion of the project beyond what was originally funded, as consultations identified the need to also engage human research ethics committee members in the project. An overview of the data collected as part of Murru Minya is presented in Box 2. To uphold and safeguard the voices and experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities, these data will be published in publications with the Lowitja Institute.

Throughout project implementation, knowledge translation to project governance and leaders was continuously undertaken. We established a website with a focus on community‐level translation where members of the academic sector and community could register to receive newsletters and project updates.

Prior to submitting manuscripts for publication, in‐process findings of the study were first shared with the research governing body. Following this, a series of personal invitations were received to present our research to community organisations and research institutes, such as the Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity Unit at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute and the Telethon Kids Institute (Western Australia). We also presented our findings at key international Indigenous health conferences, including Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health Conference (2023)9,10 and the World Indigenous Cancer Conference (2024).11 A workshop held at the World Indigenous Cancer Conference — Ethical research in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: where are we and where do we need to go? — presented key findings and questions to develop recommendations to be carried forward for the final stage of the research project. The project will be finalised in early 2025 in partnership with Lowitja Institute, and will develop practical recommendations for future health and medical research.

Murru Minya is the first national examination of ethical research and research ethics in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research. It captured the experiences and perceptions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities who have participated in research, researchers who have conducted research, and members of human research ethics committees who have approved research.

In this supplement we examine ethics approvals reported in recent research publications, examining ethical governance,12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’ processes, positioning, and experiences of health and medical research,13 the perspectives of researchers who have engaged with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research,14,15,16 human research ethics committee members’ reports on membership structures, review processes, and overall experiences and perceptions of reviewing research,17 and perceptions of how well researchers who conduct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research apply ethical research practices.16 We acknowledge that this work will not be completed within one four‐year funded project, and this supplement is not intended to provide the reader, or the institutions in which they are placed, Indigenous knowledges for selective consumption Rather, it is an invitation to address the urgent systemic change required to safeguard Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities on our terms. This work is one baarra (step) in the direction of collectively upholding and responding to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices as the leaders of the transformation required for research to have genuine impact on the path for the future.

Box 1 – Governance structures of the Murru Minya project

AH&MRC = Aboriginal Health and Medical Council of New South Wales; AIATSIS = Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Box 2 – Overview of the aim of and data collected for each baarra (step) of the Murru Minya project

|

Baarra aim |

Collected data reported in this supplement |

Collected data to be reported elsewhere |

Funding |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Baarra 1: Exploration of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’ experience with health research |

National cross‐sectional survey of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services13 |

Yarning Circles (in process with Lowitja Institute publishing) |

NHMRC Ideas grant |

||||||||||||

|

Baarra 2: Academics’ perceptions of undertaking ethical research |

Interviews with Indigenous researchers (in process with Lowitja Institute publishing) |

NHMRC Ideas grant |

|||||||||||||

|

Baarra 3: The process of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research from the perspective of HRECs |

Interviews with HREC members17 |

None (consultation‐led development) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

HREC = Human Research Ethics Committee; NHMRC = National Health and Medical Research Council. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples; here: p. 250. New York: Zed Books,1999.

- 2. McGuffog R, Chamberlain C, Hughes J, et al. Murru Minya: informing the development of practical recommendations to support ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a protocol for a national mixed‐methods study. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e067054.

- 3. National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Aug 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/8981/download?token=hrxHs075 (viewed Oct 2024).

- 4. Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council. NSW Aboriginal health ethics guidelines: key principles (v2.1). 2023. https://www.ahmrc.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/10/AHMRC_Health‐Ethics‐guidelines‐2023_01.pdf (viewed Oct 2024).

- 5. Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. marra ngarrgoo, marra goorri: The Victorian Aboriginal health, medical and wellbeing research accord. Oct 2023. https://cdn.intelligencebank.com/au/share/NJA21J/a7eD7/DX0gq/original/marra+ngarrgoo%2C+marra+goorri+‐+Accord (viewed Oct 2024).

- 6. South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute. Wardliparingga: South Australian Aboriginal health research accord. 2 Sept 2014; revised: 7 Sept 2021. https://sahmri.blob.core.windows.net/communications/ACCORD%20Companion%20Doc‐Final‐Updated‐2021.pdf (viewed Oct 2024).

- 7. Lovett R. Researching right way: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research ethics: a domestic and international review. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies; Lowitja Institute, 2013. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/3561/download?token=w4Nxp1_M (viewed Oct 2024).

- 8. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies; Lowitja Institute. Evaluation of the National Health and Medical Research Council documents: Guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research 2004 (values and ethics) and Keeping research on track: a guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples about health research ethics 2005 (keeping research on track). Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies; Lowitja Institute, 2013. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/3556/download?token=zRZP0og3 (viewed Oct 2024).

- 9. Collis F, McGuffog R. “Stop doing to and start working with”: Murru Minya‐perspectives of ethical conduct of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research [unpublished presentation]. Lowitja Institute 3rd International Indigenous Health and Wellbeing Conference, Cairns, 14–16 June 2023. https://www.lowitjaconference.org.au/program (viewed Dec 2024).

- 10. Collis F, Kennedy M. “Holding researchers to account”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community perspectives on ethical health research [unpublished presentation]. Lowitja Institute 3rd International Indigenous Health and Wellbeing Conference, Cairns, 14–16 June 2023. https://www.lowitjaconference.org.au/program (viewed Dec 2024).

- 11. Collis F, Kennedy M. Ethical research in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: where are we and where do we need to go? [unpublished presentation]. World Indigenous Cancer Conference, Melbourne, 18–20 Mar 2024. https://www.wicc2024.com/program (viewed Dec 2024).

- 12. Collis F, Booth K, Bryant J, et al. Beyond ethical guidelines: upholding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance in health and medical research. A scoping review. Med J Aust 2025; 222 (Suppl): S42‐S48.

- 13. Collis F, Booth K, Bryant J, et al. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community experiences and recommendations for health and medical research: a mixed methods study. Med J Aust 2025; 222 (Suppl): S6‐S15.

- 14. Bryant J, Booth K, Collis F, et al. Reported processes and practices of researchers applying for human research ethics approval for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a mixed methods study. Med J Aust 2025; 222 (Suppl): S25‐S33.

- 15. Booth K, Bryant J, Collis F, et al. Researchers’ self‐reported adherence to ethical principles in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research and views on improving conduct: a mixed methods study. Med J Aust 2025; 222 (Suppl): S16‐S24.

- 16. Kennedy M, Booth K, Bryant J, et al. How well are researchers applying ethical principles and practices in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research? A cross‐sectional study. Med J Aust 2025; 222 (Suppl): S49‐S56.

- 17. Kennedy M, Booth K, Bryant J, et al. Human research ethics committee processes and practices for approving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a mixed methods study. Med J Aust 2025; 222 (Suppl): S34‐S41.

No relevant disclosures.