“The gap is not a natural phenomenon. It is a direct result of the ways in which governments have used their power over many decades. In particular, it stems from a disregard for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's knowledges and solutions.”1

Health and medical research have the potential to inform policy and health service delivery, and in turn improve the health and wellbeing of Australia's First Peoples. Since first contact, however, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been subjects of health and medical research that has caused significant harm and disruption to cultural practices.2 It is well established that despite being the most researched people globally, research on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has been of little benefit.3,4 In responding to the historical and contemporary poor health and wellbeing outcomes experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, a number of government initiatives and policies have been implemented.5,6,7 These policies have influenced a threefold increase in investment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research over the past decade.8 Acknowledging the lack of benefit received by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by health and medical research, alongside a continued growth in health and medical research driven by policy, it is critical to examine how research is being conducted and, notably, how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are involved in and govern research practices.

In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) is responsible for monitoring health and medical research. A number of key ethical principles and guidelines have been produced, under the precedence of the NHMRC National statement on ethical conduct in human research (hereafter referred to as the National Statement) — a set of responsibilities to guide research practices and processes, first established in 20079 and updated in 2023.10 These documents are intended for use by researchers, institutions and ethics review bodies, including human research ethics committees (HRECs). In response to the harm caused by Euro‐Western knowledge systems, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have concurrently led recommendations for research practice since 1987.11 This has included, but is not limited to, the establishment12 and refinement13 of specific values and principles that must also be applied by researchers and HRECs when working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research14,15,16 to ensure respectful, safe and ethical practices.

Despite there being almost 200 NHMRC‐registered HRECs across the country that review and approve research,17 only three registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled ethics committees (AHRECs) have been established — in New South Wales, Western Australia and South Australia. AHRECs were established by Aboriginal communities to embed safe and responsive ethics research principles by implementing approval processes within the local community context.18 As such, AHRECs serve as an important mechanism in health and medical research practice, offering expert review, consideration and approval of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research through this Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance.19,20 AHRECs have specialist representation, expertise and knowledge with membership consisting of primarily Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who offer collective deliberation regarding the benefit, cultural safety and reciprocal and respectful research practice proposed.21 As the national investment into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research continues to grow,8 it is timely to examine research practices, including how one type of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is being upheld in the conduct of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research.

In this scoping review, we explored how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is upheld in research through a review of all literature, published over a 5‐year period, that relates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research. Our objectives were to examine what ethics approvals are being sought for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research, and determine what proportion of research upholds Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance via an AHREC, by jurisdiction and funding body type.

Methods

Research team and positioning

This review was led by two Aboriginal researchers (FC and MK) throughout all stages of the research. FC, a Gomeroi woman and PhD candidate, and MK, a Wiradjuri woman, have expertise in social and community services and have each worked in and experienced health and medical research from the perspectives of a Euro‐Western institution and a community‐controlled Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research institute. These unique perspectives and experiences shape the approach and values in conceptualising, conducting, analysing and interpreting the data presented in this review. Support was provided to the Aboriginal authors by two non‐Indigenous researchers (KB and JB) working on the review.

Study design

The conduct and reporting of this scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) statement.22 This review extends on a scoping review previously published by this research team describing the research outputs relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health since the establishment of the Closing the Gap campaign.8 A systematic search of the literature was initially conducted via the Lowitja Institute website using the search tool LIt.search23 to access all literature relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research within the PubMed database (Box 1) for the period January 2008 to December 2020.8 For this scoping review, a second search using the same search strategy was undertaken in February 2023 to update the search to December 2022 inclusive.

Eligibility criteria

Publications were included if they were published between January 2018 and December 2022 inclusive, and presented original peer‐reviewed health and medical research conducted with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Case studies, comparative studies, reviews, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts, protocols, government reports, perspective pieces and grey literature were excluded. Publications that did not directly relate to a health outcome were also excluded, including education, training, health workforce, child protection, parenting, violence and justice publications.

Study screening and data extraction

All retrieved titles and abstracts were imported into Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software (version 14). Title and abstract screening for the updated search was conducted by one author (KB) and disagreements regarding full text inclusion were discussed with two Aboriginal authors (FC and MK) until consensus was reached. Data were initially coded independently by two authors (FC and KB). To ensure consistency of coding and definitions, discussions were held with MK and JB at various intervals throughout the coding process to discuss any discrepancies, with final decisions determined by the lead researcher (MK). Each publication was then double coded by one of the Aboriginal authors (FC or MK), ensuring oversight throughout; each was read in its entirety to extract the information provided in Box 2, with particular focus on information reported in the methods, ethics approval, funding and acknowledgements sections of the publications (Box 2). Data coding disagreements were discussed, and final decisions were made by the senior Aboriginal author (MK).

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata/BE and are reported as frequencies and proportions. To understand the proportions by jurisdiction and funding body type, the following groups were made: funding bodies that were listed on the Australian Competitive Grants Register (such as NHMRC, Medical Research Future Fund and Australian Research Council) were grouped as category 1; Commonwealth and state funding from hospitals and health services (such as local area health districts and health departments) were grouped as government; and universities and research institutions were grouped as institution.

Results

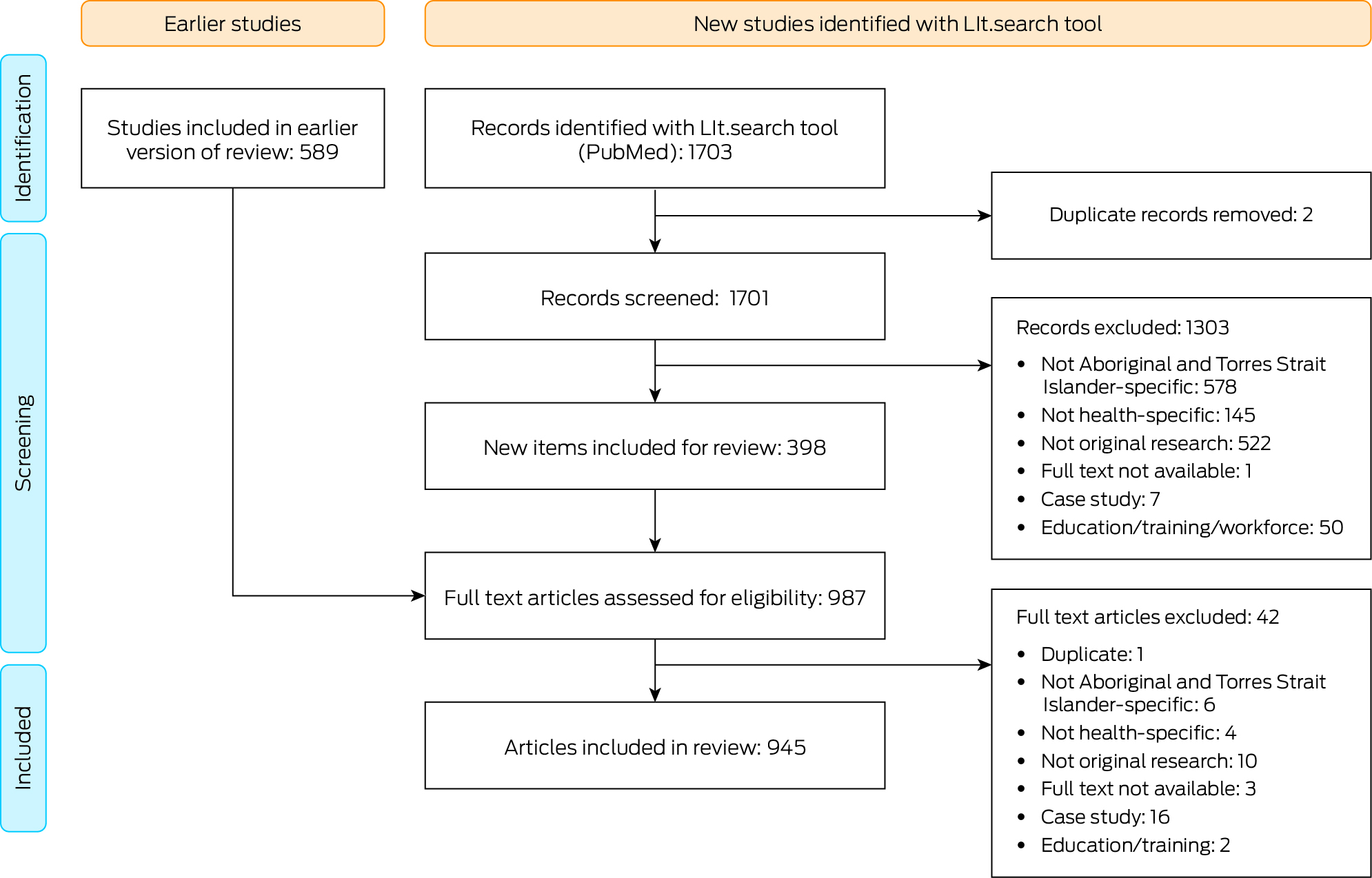

In the current review, we included 589 eligible publications from the parent review, covering the period January 2018 to December 2020. A further 1703 publications were identified from the updated search, for the period January 2021 to December 2022. Following removal of duplicates and study screening, a total of 987 publications met the inclusion criteria and were included in the full text review. Following further removal of duplicates and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, including case studies or those not relating directly to a health outcome, a total of 945 publications were included in the current review (Box 3; Supporting Information).

Box 4 presents the numbers and proportions of publications that reported receiving ethics approval by ethics body type. Fewer than half (400, 42.3%) of the publications reported obtaining AHREC approval. A substantial number of ethics approvals were obtained from a government‐based ethics committee, inclusive of health and hospital departments (394, 41.7%) and more than half of the publications reported obtaining institutional ethics approval (514, 54.4%).

Box 5 presents the numbers and proportions of publications by jurisdiction, and those with AHREC or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subcommittee approval in jurisdictions in which such committees were operating. Most were conducted in the Northern Territory (240, 25.4%) and Queensland (225, 23.8%), together representing almost half of all research conducted in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Almost one‐third of the research was conducted in states or territories where there is no AHREC (334, 35.3%). National projects comprised 12.8% (121) of research conducted.

Box 6 presents the numbers and proportions of publications of research conducted in jurisdictions with an AHREC or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subcommittee that reported obtaining AHREC or subcommittee approval, by funding body type. Publications did not consistently report obtaining Aboriginal‐specific ethics approvals within these jurisdictions across the different funding types, including 70 category 1‐funded projects, and 31 government‐funded projects. Of those publications that did not report obtaining AHREC or subcommittee approvals, a large number reported unspecified funding (34, 30%) or no funding (13, 27%).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this scoping review is the first to examine how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is being upheld in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research. We found that almost half of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research published between January 2018 and December 2022 did not report having ethics approval from an AHREC. The largest proportion of research was conducted in a jurisdiction without an AHREC. We acknowledge that the Northern Territory currently has a mechanism for subcommittee approvals that comprises a collective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, however this is situated within an institution and does not operate in a community‐controlled organisation. While we recognise that there are currently systemic barriers impacting AHREC ethical governance, including limited AHREC coverage on a jurisdictional and national level, these findings indicate that a large proportion of research may not have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance, including in jurisdictions where an AHREC operates. In the absence of AHREC approval, it is unclear how the National Statement9 is being applied to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research as determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Acknowledging the role of research to inform policy and health service delivery, these findings raise concern that knowledges informing policy may not align with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander priorities and governance processes as there is no evidence that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have reviewed, deliberated or approved the research. It is well established that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are best placed to interpret and apply the National Statement9 and ethical guidelines14,15 to ensure that research conducted is safe and of benefit to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people participating in the research.24 One such mechanism to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance of research is AHRECs. AHRECs offer external expert review, assessment and approval of research that mitigate institutional biases by a collective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. While obtaining AHREC review is not mandatory in any current ethics guidelines, the National Statement acknowledges that “The message for researchers is that there is great diversity across the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and societies. Application of these core values, and of additional cultural and local‐language protocols, should be determined by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities or groups involved in the research.”9

Aligned with the National Statement, AHRECs provide a mechanism for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance determining how and what research is conducted with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. Despite their pivotal role, we found that one‐third of research is being conducted in states and territories without an AHREC, and that only 57.9% of national research reportedly obtained approval from an AHREC despite the likelihood of the research being conducted in at least one state or territory with an AHREC. These findings are concerning given the need for national level evidence to drive policy change25 and the complex nature of multijurisdictional and national research requiring appropriate deliberations to apply the National Statement and ethics guidelines. Other researchers have reported the complexities of obtaining ethics approvals for national studies as a barrier to conducting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research.26 Acknowledging these complexities, it remains imperative that AHREC approval is sought and reported to ensure that researchers are appropriately applying ethics guidelines as determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to reduce the risk of further harm that national and multijurisdictional research has the potential to cause.

While the current landscape of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance poses systematic barriers such as a lack of national coverage, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities continue to lead the work required to uphold Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance. Funded by the Lowitja Institute, the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation and the Queensland Aboriginal and Islander Health Council are currently undertaking feasibility studies and consultations to establish AHRECs, and the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation has recently published their accord.27 Further, the Medical Research Future Fund has funded the critical work for the Lowitja Institute to establish a national AHREC.28,29 However, state and territory governments will be required to work with peak bodies in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled sector to establish and maintain appropriate AHRECs including identifying sustainable funding mechanisms. While these developments are promising, there must be simultaneous mechanisms in place to ensure that appropriate ethics approvals are sought and reported on by funding bodies, researchers, institutions and journals, including ethical reporting and accountability.30

In our study, we found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance via an AHREC was consistently not upheld, including in jurisdictions where one operates. With the implementation of priority and target funding schemes, the volume of research being conducted is likely to continue to increase. While increased investment in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research is welcomed,31 the National Statement must be adhered to in full, which includes upholding the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. We urge funding bodies to consider their responsibilities in ensuring that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is being upheld, including AHREC approval, before funds are released. Acknowledging that research is also being conducted without funding, researchers and their institutions as well as non‐Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethics committees must take responsibility to ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is upheld in all research conducted regardless of the size and scope of the project.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical guidelines were developed by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities as a protective measure, acknowledging the historical harms caused and the continued risk and harm that research has the potential to cause. Without appropriate reporting and utilisation of AHRECs, we are unable to conclude that current research in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health is consistently safe and beneficial from the perspective of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Researchers must seek AHREC approvals for research conducted in states where there is an operational AHREC. Upholding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is the shared responsibility of researchers, funding bodies, and institutions, who are required to consider their role in ensuring that mechanisms of accountability are embedded to uphold this ethical governance, to ensure that health and medical research is safe and beneficial to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Limitations

This review could only examine published literature in which the researchers have appropriately reported on ethics approval and funding bodies, and we acknowledge that researchers might have experienced limitations by journal publishing practices excluding the relevant details for this review. Another limitation of our study is that not all researchers specifically reported obtaining ethics approval from the Aboriginal Ethics Sub‐Committee in the Northern Territory, however studies were coded as having received approval from the subcommittee given the likelihood that this was part of the standard process of the combined NT Department of Health and Menzies School of Medical Research human research ethics committee.

Conclusion

AHRECs are an important mechanism for upholding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance of research that aims to improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. We found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance is not being consistently upheld via AHREC approval, even in jurisdictions where one operates. Acknowledging that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research ethics guidelines were established due to harm caused to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, these results suggest that there is a high risk associated with current research practice. Research is not consistently being deemed safe, respectful and beneficial for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by appropriate AHREC review and approval. Researchers, funding bodies, institutions and journals share collective responsibility to ensure that all research conducted with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has justifiable benefit and impact for our health and wellbeing outcomes. We join calls for the establishment of an AHREC in all jurisdictions and nationally. Furthermore, we urge funding bodies and institutions to uphold the requirements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance to be embedded within policies and practices in a shared commitment to the responsibilities outlined in the National Statement to ensure that research is deemed safe, respectful and beneficial by and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Box 1 – Summary of search terms*

The following Lowitja pre‐defined terms for “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health” were used:

(((((australia[mh] OR australia*[tiab]) AND (oceanic ancestry group[mh] OR aborigin*[tiab] OR indigenous[tw])) OR (torres strait* islander*[tiab])) AND medline[sb]) OR ((((au[ad] OR australia*[ad] OR australia*[tiab] OR northern territory[tiab] OR northern territory[ad] OR tasmania[tiab] OR tasmania[ad] OR new south wales[tiab] OR new south wales[ad] OR victoria[tiab] OR victoria[ad] OR queensland[tiab] OR queensland[ad]) AND (aborigin*[tiab] OR indigenous[tiab])) OR (torres strait* islander*[tiab])) NOT medline[sb]) AND English[la])

MeSH = medical subject heading. * Terms in brackets are PubMed field codes (mh, MeSH heading; tiab, title or abstract; tw, text words; sb, subset; ad, affiliation; la, language).

Box 2 – Data extraction and coding details

|

Data extracted |

Details |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Article details |

Year of publication was recorded. |

||||||||||||||

|

Jurisdiction of data used |

For each publication, the states and/or territories where data collection occurred was recorded (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, Australian Capital Territory, Western Australia, South Australia, Northern Territory, or national). Publications of research conducted in the Torres Strait Islands were coded as such. Publications that did not explicitly report the state where data collection was undertaken were coded as unspecified. Publications that self‐identified as being national in scope, or where data collection was described as being conducted in five or more states and/or territories, were coded as national studies. Publications that stated that data collection occurred in multiple states and/or territories but fewer than five were coded for each jurisdiction. |

||||||||||||||

|

Project funding body |

The name of any organisation listed as funding the research was extracted and coded by funding body type: category 1 (eg, NHMRC, MRFF, ARC), government, university, charity funding (philanthropic), unfunded and other. Publications that did not explicitly report project funding body were coded as unspecified. |

||||||||||||||

|

Ethics approval body |

The names of all HRECs from which approval was stated to have been obtained were recorded. The 2022 NHMRC‐registered HREC list17 was used to define HREC type. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ARC = Australian Research Council; HREC = human research ethics committee; MRFF = Medical Research Future Fund; NHMRC = National Health and Medical Research Council. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses flow diagram of updated reviews

Box 4 – Numbers and proportions of publications that reported receiving ethics approval, by ethics approval body type*

|

Ethics approval body type |

Number |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of publications |

945 |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled HREC† |

400 (42.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subcommittee‡ |

227 (24.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies |

5 (0.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Institution |

514 (54.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Government (including health and hospital departments) |

394 (41.7%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Unspecified |

79 (8.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

18 (1.9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

None |

14 (1.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

HREC = human research ethics committee. * Studies were coded across multiple categories if multiple funding bodies or ethics approvals were specified, therefore numbers do not add to 945. † These types of ethics approval bodies were only in New South Wales, Western Australia and South Australia. ‡ This type of ethics approval body was only in the Northern Territory. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Numbers and proportions of publications by jurisdiction, and those that reported Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled human research ethics committee (AHREC) or subcomittee approval*

|

Jurisdiction |

Number of publications |

Number with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled ethics committee or subcomittee approval |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of publications |

945 |

|

|||||||||||||

|

With an AHREC |

|

399 (88.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Western Australia |

149 (15.8%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

New South Wales |

178 (18.8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

South Australia |

124 (13.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

With a subcommittee |

|

223 (92.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Northern Territory |

240 (25.4%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Without an AHREC or subcommittee |

|

— |

|||||||||||||

|

Queensland |

225 (23.8%) |

|

|||||||||||||

|

Victoria |

48 (5.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Tasmania |

6 (0.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Australian Capital Territory |

6 (0.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Torres Strait Islands |

20 (2.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

National |

121 (12.8%) |

70 (57.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Unspecified |

29 (3.1%) |

— |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Publications were coded across multiple jurisdictions if they reported on research conducted in more than one state, but not nationally, therefore numbers do not add to 945. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Numbers and proportions of publications of research conducted in jurisdictions with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled ethics committee (AHREC) or subcomittee that reported obtaining AHREC or subcommittee approval, by funding body type

|

|

|

Publications of research conducted in jurisdictions with an AHREC or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled ethics committee or subcommittee |

Publications of research conducted in a jurisdiction with an AHREC* |

Publications of research conducted in a jurisdiction with an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander subcommittee† |

|||||||||||

|

Funding body type |

Total number |

Number with AHREC and subcommittee approval |

Number without AHREC and subcommittee approval |

Number with AHREC approval |

Number without AHREC approval |

Number with subcommittee approval |

Number without subcommittee approval |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Category 1 |

390 |

320 (82%) |

70 (18%) |

216 (83%) |

45 (17%) |

104 (81%) |

25 (19%) |

||||||||

|

Government |

158 |

127 (80%) |

31 (20%) |

98 (84%) |

19 (16%) |

29 (71%) |

12 (29%) |

||||||||

|

Institution |

64 |

53 (83%) |

11 (17%) |

40 (89%) |

5 (11%) |

13 (68%) |

6 (32%) |

||||||||

|

Charity |

85 |

70 (82%) |

15 (18%) |

50 (88%) |

7 (12%) |

20 (71%) |

8 (29%) |

||||||||

|

Other |

74 |

63 (85%) |

11 (15%) |

41 (89%) |

5 (11%) |

22 (79%) |

6 (21%) |

||||||||

|

Unspecified |

113 |

79 (70%) |

34 (30%) |

56 (76%) |

18 (24%) |

23 (59%) |

16 (41%) |

||||||||

|

Unfunded |

48 |

35 (73%) |

13 (27%) |

20 (77%) |

6 (23%) |

15 (68%) |

7 (32%) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Included jurisdictions were New South Wales, Western Australia and South Australia. † Northern Territory was the only included jurisdiction. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 16 April 2024, accepted 28 October 2024

- Felicity Collis (Gomeroi)1

- Kade Booth1

- Jamie Bryant1

- Michelle Kennedy (Wiradjuri)1

- University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

We acknowledge that this research was conducted across unceded lands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and pay respect to the elders and caretakers of the lands, seas, sky and waterways. We acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the knowledge holders and pay respect to their wisdom and processes for knowledge productions and knowledge sharing.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Review of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap: study report. Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2024. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/closing‐the‐gap‐review/report/closing‐the‐gap‐review‐report.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 2. Thomas DP, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Changing discourses in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research, 1914–2014. Med J Aust 2014; 201: S15‐S18. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2014/201/1/changing‐discourses‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐research‐1914

- 3. Bainbridge R, Tsey K, McCalman J, et al. No one's discussing the elephant in the room: contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian health research. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 696.

- 4. Tuhiwai Smith L. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples. 3rd ed. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.

- 5. Australian Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Closing the Gap on Indigenous disadvantage: the challenge for Australia. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, 2009. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2012/closing_the_gap.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 6. Australian Government. National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Canberra: Australian Government, 2020. https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/national‐agreement‐ctg.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 7. Australian Government. Commonwealth Closing the Gap 2023 annual report and Commonwealth Closing the Gap 2024 implementation plan. Canberra: National Indigenous Australians Agency, 2024. https://www.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2024‐02/ctg‐annual‐report‐and‐implementation‐plan.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 8. Kennedy M, Bennett J, Maidment S, et al. Interrogating the intentions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: a narrative review of research outputs since the introduction of Closing the Gap. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 50‐57. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/217/1/interrogating‐intentions‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐narrative

- 9. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, Universities Australia. National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2007 (updated 2018) [rescinded]. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/19896/download?token=o‐erpn_z (viewed Apr 2024).

- 10. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, Universities Australia. National statement on ethical conduct in human research 2023. Canberra: NHMRC, 2023. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/19531/download?token=rpY3‐bU5 (viewed July 2024).

- 11. National Aboriginal and Islander Health Organisation. Report of the national workshop on ethics of research in Aboriginal health. 1987. http://esvc000239.bne001tu.server‐web.com/Downloads/CRIAH%20Tools%20for%20Collaboration%20ver1%20December2007/1%20Background/Report%20of%20the%20National%20Workshop%20on%20Ethics%20in%20Research%20in%20Aboriginal%20health.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 12. National Health and Medical Research Council. Guidelines on ethical matters in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: NHMRC, 1991. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/847323 (viewed Dec 2024).

- 13. Lovett R. Researching right way: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research ethics: a domestic and international review. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and Lowitja Institute, 2013. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/research‐policy/ethics/ethical‐guidelines‐research‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐peoples (viewed Apr 2024).

- 14. National Health and Medical Research Council. Values and ethics: guidelines for ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: NHRMC, 2003. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/9106/download?token=ag3509K2 (viewed Apr 2024).

- 15. National Health and Medical Research Council. Keeping research on track II: a companion document to Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Canberra: NHMRC, 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/file/8976/download?token=vSzVyLgi (viewed Apr 2024).

- 16. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. AIATSIS code of ethics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research. Canberra: AIATSIS, 2020. https://aiatsis.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020‐10/aiatsis‐code‐ethics.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 17. National Health and Medical Research Council. List of human research ethics committees registered with NHMRC. Canberra: NHMRC, 2024. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/attachments/Committee/HREC‐Human‐Research‐Ethics‐Committees‐registered‐with‐NHMRC‐LIST.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 18. Finlay SM, Doyle M, Kennedy M. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander human research ethics committees (HRECs) are essential in promoting our health and wellbeing. Public Health Res Pract 2023; 33: 3322312.

- 19. Burchill LJ, Kotevski A, Duke DL, et al. Ethics guidelines use and Indigenous governance and participation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a national survey. Med J Aust 2023; 218: 89‐93. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/2/ethics‐guidelines‐use‐and‐indigenous‐governance‐and‐participation‐aboriginal‐and

- 20. Duke DLM, Prictor M, Ekinci E, et al. Culturally adaptive governance—building a new framework for equity in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: theoretical basis, ethics, attributes and evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 7943.

- 21. Finlay S, Keed V, Kelly D, et al. Aboriginal human research ethics committees ensuring culturally appropriate research. Eur J Public Health 2020; 30 Suppl 5: ckaa166.173.

- 22. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169: 467‐473.

- 23. Tieman JJ, Lawrence MA, Damarell RA, et al. LIt.search: fast tracking access to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health literature. Aust Health Rev 2014; 38: 541‐545.

- 24. Finlay SM, Doyle M, Kennedy M. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander human research ethics committees (HRECs) are essential in promoting our health and wellbeing. Public Health Res Pract 2023; 33: 3322312.

- 25. Vivian A, Halloran MJ. Dynamics of the policy environment and trauma in relations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the settler‐colonial state. Crit Soc Policy 2021; 42: 626‐647.

- 26. McGuffog R, Bryant J, Booth K, et al. Exploring the reported strengths and limitations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a narrative review of intervention studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 3993.

- 27. Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. marra ngarrgoo, marra goorri: the Victorian Aboriginal Health, Medical and Wellbeing Research Accord. Melbourne: VACCHO, 2023. https://www.vaccho.org.au/accord (viewed Apr 2024).

- 28. University of Newcastle. Almost $3m grant secured for sector‐first in Indigenous health research [news]. 30 June 2023. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/newsroom/featured/almost‐3m‐grant‐secured‐for‐sector‐first‐in‐indigenous‐health‐research (viewed Apr 2024).

- 29. Lowitja Institute. 2023 annual report. Melbourne: Lowitja Institute, 2023. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/03/LI_Annual_Report_2023_LR.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 30. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 31. Australian Government Department of Health and Age Care. Indigenous health research fund. Canberra: Australian Government, 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/mrff‐indigenous‐health‐research‐fund (viewed Apr 2024).

Abstract

Objectives: To examine what ethics approvals are being sought for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research, and to determine what proportion of this research upholds Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance via an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled human research ethics committee (AHREC) by jurisdiction and funding body type.

Study design: Scoping review of all original, peer‐reviewed health and medical literature published over a 5‐year period (January 2018 to December 2022).

Data sources: Extending on a previous review, the search tool LIt.search was used to access all literature relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research.

Results: 589 eligible publications were included from the parent review, and a further 1703 publications were identified from the updated search. A total of 945 publications were included. A substantial number of ethics approvals were obtained from government‐based ethics committees (394, 41.7%). More than half of the publications reported obtaining institutional ethics approval (514, 54.4%). Less than half (400, 42.3%) reported obtaining AHREC approval. Almost one‐third of publications were on research that was conducted in states or territories where there is no AHREC (334, 35.3%). Publications did not always report obtaining AHREC approvals, including in jurisdictions where one operates.

Conclusions: We found a concerning lack of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance reported in health and medical research. Acknowledging that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethics guidelines and AHRECs were established due to harm caused to communities, these results suggest a high risk, with research not consistently being deemed safe, respectful and beneficial with appropriate AHREC ethics review and approval. We join calls for the establishment of AHRECs in all jurisdictions and nationally. Furthermore, we urge funding bodies and institutions to uphold requirements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical governance in research and funding agreements, as well as institutional policies and procedures.