Effective treatment in the form of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) modulator therapy targeting the most common gene mutations is now available for over 90% of people with cystic fibrosis over the age of 2 years. This treatment results in improvement of lung function and nutritional status.1 However, it is not known whether these effects will be sustained or have a wider influence on the multiple organs affected by cystic fibrosis if introduced early in life. Hence, many Australian people with cystic fibrosis will continue to live with the possibility of organ failure, albeit fewer than in previous generations. There is agreement that single organ transplantation in a patient with organ failure is medically appropriate and ethically justifiable. However, cystic fibrosis can result in the insidious failure of several organs simultaneously, such that single organ transplant is neither possible nor life prolonging. In such circumstances, multiple organ transplant would be considered. However, there are several complex medical factors that transplant teams need to consider, such as feasibility (infrastructure and centralisation of services) and benefit to the patient (usefulness) along with the ethical consideration of organ rationing when donors are limited. Due to recent treatment improvements, the need for multiple organ transplants in people with cystic fibrosis is decreasing; however, we still need to ensure equity regarding decision making. In this article, we explore the ethical principles associated with multiple organ transplant in people with cystic fibrosis in the current setting, using a fictional patient representative of a typical patient with cystic fibrosis.

The patient

A referral is received from the local cystic fibrosis service for a 22‐year‐old man (Box 1) for consideration of a combined lung and liver transplant. He has a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of less than 30%, life‐threatening haemoptysis and worsening nutrition despite full supplemental feeding. His genotype (G543X and N1303K) was not responsive to CFTR modulator therapy.2 In addition, he has portal hypertension because of advanced cystic fibrosis‐related liver disease and has suffered life‐threatening variceal bleeding. He has read about multiple organ transplant in cystic fibrosis and has discussed this with his team, who agree that this is an option to explore, given a substantially diminished quality of life and poor survival with severe dual organ disease. But is it ethically appropriate to list him for transplantation?

Feasibility and criteria for transplant

Multiple organ transplant in people with cystic fibrosis has been accepted as a treatment option globally (North America, Europe, England, Australia and New Zealand) and increasing numbers are being performed.3,4,5,6 Multiple organ transplant has been demonstrated to provide a significant advantage to recipients including survival, reducing the need for further transplants because of sequential organ failure and reduced immunological sensitisation.7 One practical question is whether such a transplant would be feasible. With our fictional patient, the transplant is seen to be feasible if the correct transplant infrastructure is available locally, including appropriately trained surgical teams and post‐operative care teams experienced in transplant of both organs, which is not always the case and is a substantial barrier to multiple organ transplant worldwide.8

Another challenge is whether the patient fulfils medical criteria for transplant of both organs. These criteria can overlap with the ethical considerations (see below) but include both evaluation of need for transplantation (eg, severity of illness, likelihood of deterioration without transplant) and benefit of procedure (sufficient chance of short or medium term survival to offer the procedure). This can pose a significant problem for transplant teams and although it appears well defined for the lung,9 there remain concerns around the liver, due to the variations in the natural history of liver disease in cystic fibrosis. In addition to this, scoring systems of liver dysfunction used to predict mortality are generic and underestimate the disease burden in cystic fibrosis.10 Standardisation of criteria would promote clarity and transparency in organ allocation. As there are no standard national or international guidelines available for patients in need of multiple organ transplants, each regional transplant service (or in this case, multiple services in each state) in Australia is required to make their own determination of an individual patient's need for organs and the process relies on multidisciplinary meetings during the clinical journey of the person with cystic fibrosis.11

For this fictional patient, they have capacity to benefit from transplantation of both lung and liver and local resources are available. What is next to consider?

Allocation (including the transplant lifeboat problem)

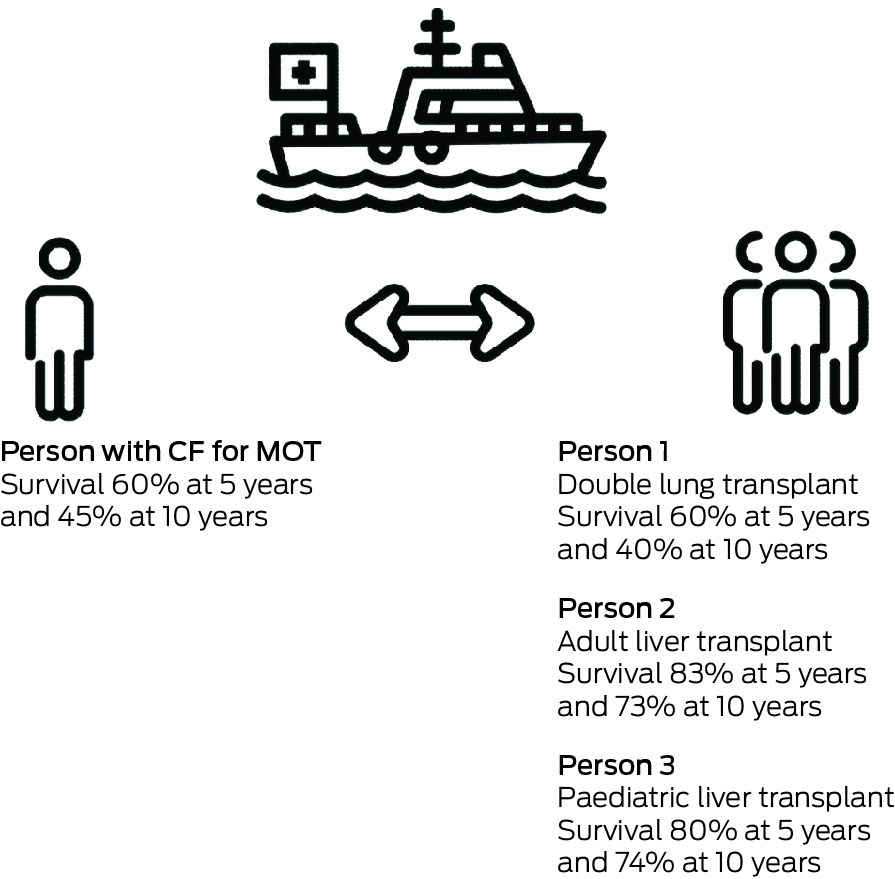

The next step is to assess whether it is fair to allocate several organs to a single patient when there are many others awaiting single organ transplant. This is a version of what we could call the transplant lifeboat problem.12,13 Our patient (Box 2; “Person with CF for MOT”) requires two lungs and a liver. If he does not receive transplantation, those organs would be available to two or perhaps three other patients (if a split liver transplantation). Based on local data,2 our patient will have a similar survival outcome to a double lung transplantation (for other indications) at five years and ten years. Patients who receive a liver transplant have an even greater survival advantage.

There are several reasons that might be given for allocating the lungs and liver to the cystic fibrosis patient. One might be a justice‐based desire (perhaps drawing on the Rawlsian principle14) to benefit those who are worse off (ie, with dual organ failure), or alternatively, drawing on the “rule of rescue”, and the human instinct to, where possible, save identifiable individuals in acute peril.15,16

But there is a strong justice‐based argument that it is, prima facie, wrong to prioritise the needs of a single patient over the equal needs of several others. Although some philosophers have disagreed, there is a widespread intuition (shared by members of the public) that in a lifeboat dilemma, we should choose to save more rather than fewer lives.12,13 How then might multiple organ transplants be justified? One situation where it would be ethically straightforward is where there are no other competing patients (see below). Another way of justifying it would be if the patient would be eligible (and likely to receive) single organs sequentially. In that case, receiving two organs at the same time would have no net effect on organ availability for others.

Prioritisation

The next question is how does one prioritise this on the waiting list? Two dominant ethical considerations in transplant prioritisation are urgency and benefit. These values are prioritised in many organ allocation systems and by the public.17 This includes the chance of survival if patients remain on the waiting list, and the chance (and duration) of survival if transplanted. These two variables may compete, since patients who are sicker (eg, with multiple organ failure), may have a higher chance of dying on a waiting list, but also a lower chance of long term survival (if transplanted) than other patients who are waiting. This applies to people with cystic fibrosis requiring multiple organ transplant where the natural history of individual organ failure is unpredictable, making decisions around timing and graft selection difficult and results in longer waiting times, protracted morbidity and unnecessary early death if the transplant is left too late.18

One scenario where it is clearly appropriate to prioritise a person with cystic fibrosis for a multiple organ transplant is where the patient is eligible with a match for the organs, and there are no other matching (with respect to biological requirements eg, blood group) or similarly urgent patients needing single organ transplantation. Another situation would be where a person with cystic fibrosis in dual organ failure is sicker and more likely to die without transplantation than other patients awaiting a single organ. Where there is a reasonable hope that those other patients will be able to live long enough to receive an organ (on another occasion), it would be ethical to prioritise the patient needing a multiple organ transplant. On the other hand, where there are two (or more) patients with single organ failure (eg, lung or liver failure) who are equally unwell (likely to die soon without transplantation) and would equally benefit from transplantation as a patient with dual organ failure, following the lifeboat analogy, we should choose to save more lives rather than fewer lives and prioritise the patients needing single organs.

One practical consideration affecting prioritisation is the pool of organs available. Decisions for multiple organ transplants are made by local teams for local donors and recipients only, while patients needing single organs who are very unwell can be listed nationally. This may increase the opportunities for patients with single organ failure to receive organs, and may justify giving some priority to local patients needing multiple organ transplants. A separate national waiting list for multiple organ transplant patients (in general and in those with cystic fibrosis) has been proposed by the American United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)8 and may avoid the need for special prioritisation of multiple organ transplantation. Regardless of the system used for prioritisation, there should be regular review of the outcomes, such as patient survival, graft survival and quality of life.

Conclusion

We have argued that a multiple organ transplant can be justified for our fictional patient with cystic fibrosis. The procedure is feasible and he has capacity to benefit substantially. The allocation of two organs to one recipient is justifiable in situations that will not lead to several other patients missing out on an organ and dying while on the transplant waiting list. Local prioritisation of our patient on a transplant waiting list could be justified as his transplantation is more pressing because of multiple organ failure.

The increasing requests for multiple organ transplants leave us with the obligation to develop a system that is transparent and audited regularly to allow for a fair approach to such patients. This would be the role of governing bodies such as the Transplant Society of Australia and New Zealand. Increased use of CFTR modulators may mean that situations such as this are less likely in the future but that makes it more imperative to get it right now.

Box 1 – Clinical data for a fictional patient whose story was constructed for the purpose of this work but nevertheless is representative of a person with cystic fibrosis who would be referred to our service

|

Characteristic |

Clinical data |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Gender |

Male |

||||||||||||||

|

Age, years |

22 |

||||||||||||||

|

BMI, kg/m2 |

17 |

||||||||||||||

|

Pancreatic enzyme therapy/Gastrostomy feeds? |

Yes |

||||||||||||||

|

Diabetes/Altered glucose tolerance? |

No |

||||||||||||||

|

Admissions to hospital in past 12 months |

8 |

||||||||||||||

|

Average stay in hospital, days |

8 |

||||||||||||||

|

Education and social situation |

Year 3 in a science degree at university, and lives at home with supportive family |

||||||||||||||

|

FEV1 predicted, % |

30 |

||||||||||||||

|

Chest computed tomography |

Widespread bronchiectasis |

||||||||||||||

|

Sputum cultures |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Mycobacterium spp negative |

||||||||||||||

|

Haemoptysis requiring embolisation in last 12 months? |

Yes |

||||||||||||||

|

Portal hypertension? |

Yes |

||||||||||||||

|

Oesophageal varices requiring banding in last 12 months? |

Yes |

||||||||||||||

|

MELD score |

14 |

||||||||||||||

|

Renal function |

Normal |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

BMI = body mass index; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; MELD score = Model For End‐stage Liver Disease. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – The transplant lifeboat: based on a famous philosophical thought experiment. Imagine you are manning the sole coastguard boat on duty. There are three people on one lifeboat 50 miles due north, and one person on another lifeboat 50 miles due south. A storm is brewing and it is highly likely you will only be able to reach one lifeboat before the storm overturns them and the people drown. Which lifeboat should you set out to save?12,13

CF = cystic fibrosis; MOT = multiple organ transplant.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Middleton PG, Mall MA, Dřevínek P, et al. Elexacaftor‐tezacaftor‐ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1809‐1819.

- 2. Colombo C, Ramm GA, Lindbold A. Characterization of CFTR mutations in people with cystic fibrosis and severe liver disease who are not eligible for CFTR modulators. J Cyst Fibros 2023; 22: 263‐265.

- 3. Wilson T, Illhardt T, Fink M, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis: 30 years of experience in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Hepatology 2023; 78 Suppl 1: S480.

- 4. Mendizabol M, Reddy KR, Casulllo J, et al. Liver transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis: analysis of United Network for organ sharing data. Liver Transpl 2011; 17: 243‐250.

- 5. Mallea J, Bolan C, Cortese C, Harnois D. Cystic fibrosis‐ associated liver disease in lung transplant recipients. Liver Transpl 2019; 25: 1265‐1275.

- 6. Desai CS, Gruessner A, Habib S, et al. Survival of cystic fibrosis patients undergoing liver and liver‐lung transplantations. Transplant Proc 2013; 45: 290‐292.

- 7. Bhama JK, Pilewski JM, Zalondis D, et al. Does simultaneous lung‐liver transplantation provide an immunologic advantage compared with isolated lung transplantation? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 141: e36‐e38.

- 8. Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network. Ethical implications of multi‐organ transplants [OPTN/UNOS public comment proposal]. OPTN, 2019. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2801/ethics_publiccomment_20190122.pdf (viewed Oct 2023).

- 9. Paraskeva M, Levin KC, Westall GP, Snell GI. Lung transplantation in Australia, 1986‐2018: more than 30 years in the making. Med J Aust 2018; 208: 445‐450. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/208/10/lung‐transplantation‐australia‐1986‐2018‐more‐30‐years‐making

- 10. Freeman JA, Sellers ZM, Mazariegos G, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to pretransplant and posttransplant management of cystic fibrosis‐associated liver disease. Liver Transpl 2019; 25: 640‐657.

- 11. Ramos KJ, Smith PJ, McKone EF, et al. Lung transplant referral for individuals with cystic fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Consensus Guidelines. J Cyst Fibros 2019; 18: 321‐333.

- 12. Arora C, Savulescu J, Maslen H, et al. The intensive care lifeboat: a survey of lay attitudes to rationing dilemmas in neonatal intensive care. BMC Med Ethics 2016; 17: 69.

- 13. Taurek JM. Should the numbers count? Philos Public Aff 1977; 6: 293‐316.

- 14. Rawls J. A theory of justice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1971.

- 15. Reese PP, Veatch RM, Abt PL, Amaral S. Revisiting multi‐organ transplantation in the setting of scarcity. Am J Transplant 2014; 14: 21‐26.

- 16. Harris J. Deciding between patients. In: Kuhse H, Singer P, editors. A companion to bioethics. Oxford, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell, 2009; pp. 333‐350.

- 17. Drezga‐Kleiminger M, Demaree‐Cotton J, Koplin J, et al. Should AI allocate livers for transplant? Public attitudes and ethical considerations. BMC Med Ethics 2023; 24: 102.

- 18. Bell PT, Carew A, Fiene A, et al. Combined heart‐lung‐liver transplant for patients with cystic fibrosis: the Australian experience. Transplant Proc 2021; 53: 2382‐2389.

This research was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust [203132/Z/16/Z].

Dominic Wilkinson was funded in part by the Wellcome Trust [203132/Z/16/Z]. The funders had no role in the preparation of this manuscript or the decision to submit for publication. No other funding was received to complete this work by the other authors. For the purpose of open access, Dominic Wilkinson has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.