In November 2023, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released its 2022–23 Patient Experience Survey data.1 This latest release shows that many Australians struggle to afford the medicines they need and that cost barriers to access have increased compared with the previous year.

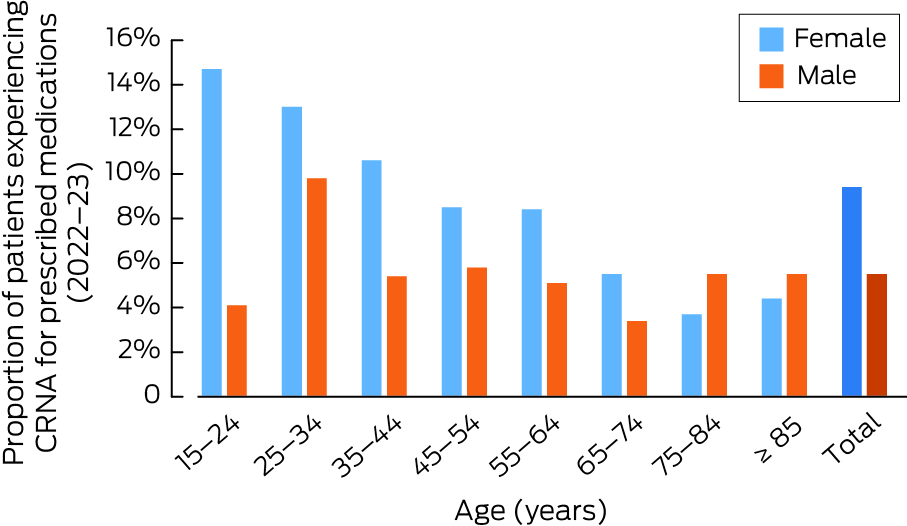

Women, younger people and those in poorer health are particularly affected. The data show that 9.4% of women compared with 5.5% of men reported cost‐related non‐adherence to medications (medication‐CRNA) (ie, delaying or not filling scripts due to cost) prescribed by their general practitioner in the previous 12 months.2 The proportion increases for younger women to 14.7% for 15–24‐year‐olds and to 13% for 25–34‐year‐olds (Box 1). However, considering that 8.4% of women (and as high as 11.3% for women aged 25–34 years) at least once delayed seeing or did not see a general practitioner,2 and 12.2% (and as high as 20.3% for 25–34‐year‐olds) at least once delayed or did not see a specialist due to cost,3 the proportion of women directly or indirectly affected by medication‐CRNA would be even higher.

Younger Australians are more likely to experience cost barriers to care than older Australians. A 25–34‐year‐old is 2.7 times more likely to experience medication‐CRNA than a 75–84‐year‐old, 3.1 times more likely to delay visiting or not visit a general practitioner due to cost,2 and 3.8 times more likely to delay visiting or not visit a specialist due to cost.3 For women, the discrepancy is much more pronounced, with 25–34‐year‐olds 3.5 times more likely to experience medication‐CRNA than 75–84‐year‐olds, 3.8 times more likely to delay visiting or not visit a general practitioner, and 4.8 times more likely to delay visiting or not visit a specialist due to cost.

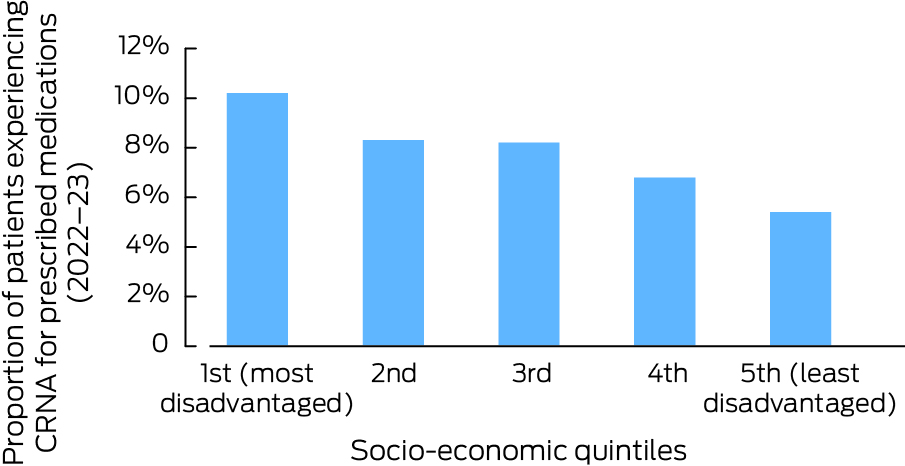

Health status also plays an important part, with 15% of individuals in fair or poor health experiencing medication‐CRNA (2.3 times higher than those in good health) and 11.8% delay visiting or not visit a general practitioner due to cost (1.8 times higher).4 For specialist visits the discrepancy was not as stark.5 The most socio‐economically disadvantaged people were also almost twice as likely to delay or not seek treatment than the most advantaged (Box 2).4

The de facto rate of medication‐CRNA is necessarily higher than what is reported in the ABS's survey. Their data are collected in the context of general practice visits only, so they would not include medicines prescribed by specialists. This is a significant lacuna since 42.2% of those surveyed needed to see a specialist,6 and it is reasonable to assume many of these patients would be prescribed some medication. The Australians that miss out on seeing a general practitioner or specialist due to cost would not get the chance to be prescribed medication.

Empirical evidence also supports the fact that the overall proportion of Australians experiencing medication‐CRNA across the entire population and all medical encounters is higher than the ABS data indicate. A survey published in 2023 found that 21.9% of people living in Australia who were aged 45 years or older, and were currently taking prescription medicines, had experienced medication‐CRNA at some point in the previous 12 months.7 This result is exactly replicated by another independently conducted survey of 11 000 people during the same general period, although the sample in this case was not limited to a specific age group.8 By contrast, the ABS’ Patient Experience Survey reports medication‐CRNA rates as high as 7.4% (45–54‐year‐olds) and low as 4.3% (65–74‐year olds) for patients aged 45 years and older.

There are important data that the ABS survey does not collect and is essential to understand. The experience of patients who can only afford their medications by making budget sacrifices that substantially affect their lifestyle is not captured. The aforementioned study of Australians aged 45 years and older found that 17.7% of people taking prescription medications had to take one or more of the following measures to buy their medicines at some point in the previous 12 months: skipping meals, not paying bills, borrowing money, selling assets, getting a loan, or drawing down a mortgage.7 Others resorted to importing cheaper medications from abroad via online platforms. A study published in 2019 estimated that out‐of‐pocket health care expenditure drives hundreds of thousands of Australians into income poverty each year, with 285 000 entering poverty in 2014.9 Therefore, the fact patients do find ways to pay for medicines does not mean they are affordable. This is supported by the fact that 30% of Australians consider medications to be unaffordable despite the relatively low rates of medication‐CRNA reported by the ABS.8

To support evidence‐based policy reform to improve medicine access, more data on medication‐CRNA across the entire spectrum of medical services, not only general practice services, are required. We also need to understand how many people are prescribed medicines not subsidised by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which adds an additional cost barrier for patients. This would include taking account of the prevalence and costs of off‐label prescribing, which is generally not subsidised by the PBS but is an important part of clinical practice.10

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, spending on non‐PBS medicines represents the largest category of out‐of‐pocket spending by Australians by far, accounting for about a third of the total.11,12 However, the data do not distinguish between prescription‐only and other medications such as vitamins and complementary therapies and so it is difficult to interpret their significance. Nevertheless, based on what we know about the rising cost of medicines,13 and the high rate of off‐label prescribing (which is generally not PBS‐subsidised) in clinical practice,10 it is reasonable to assume a large portion of this spending is on prescription medicines until evidence emerges to the contrary. In fact, one of the aims of the Therapeutic Goods Administration's new Medicines Repurposing Program is to improve equitable access to treatment by registering off‐label medicine uses of public health value so that they can be subsidised.14

Addressing the affordability of medications is critical for reigning in out‐of‐pocket spending overall and improving access to medical treatment. In addition, we need to consider more carefully how limited resources are spent, as over 50% of all pharmaceutical spending in high income countries like Australia is directed towards only treating 2–3% of patients.15 Of the top 50 PBS medicines by government expenditure in 2021–2022, 25 had fewer than 60 000 subsidised prescriptions yet cost the government $3.7 billion combined — a quarter of all PBS spending in that year ($14.7 billion).16

Finally, there are people who suffer invisibly from cost barriers to medications: patients who are prescribed inferior medicines (eg, an older medication that is less effective than a newer but also more expensive medication) or no medication at all after a discussion of costs with their doctor. Since there is no script, written data on this cost‐motivated inferior treatment are never captured but are of great importance in an era when medicines prices for the newest drugs continue to rise and break new records, becoming further out of reach for patients.13

Box 1 – Cost‐related non‐adherence (CRNA) to medications in general practice according to age and gender

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23 financial year [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2024).

- 2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23 financial year (table 5.3) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2024).

- 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23 financial year (table 11.3) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2024).

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23 financial year (table 6.2) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2024).

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23 financial year (table 12.2) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2024).

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient experiences, 2022–23 financial year (table 10) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐services/patient‐experiences/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2024).

- 7. Ghinea N, Roberts A, Prvan T, Rogers W. The incidence of personal importation of prescription medicines among Australians 45 and older: a cross‐sectional survey. Aust Health Review 2023; 47: 694‐699.

- 8. Healthengine and Australian Patients Association. Australian Healthcare Index, November 2022 (report 4) [website]. Perth: Healthengine, 2022. https://australianhealthcareindex.com.au/wp‐content/uploads/2022/11/Australian‐Healthcare‐Index‐Report‐Nov‐22.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 9. Callander EJ, Fox H, Lindsay D. Out‐of‐pocket healthcare expenditure in Australia: trends, inequalities and the impact on household living standards in a high‐income country with a universal health care system. Health Econ Rev 2019; 9: 10.

- 10. Mellor JD, Van Koeverden P, Yip SWK, et al. Access to anticancer drugs: many evidence‐based treatments are off‐label and unfunded by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Intern Med J 2012; 42: 1224‐1229.

- 11. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Patients’ out‐of‐pocket spending on Medicare services 2016–17 [Cat. No. HPF 35]. Canberra: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/health‐welfare‐expenditure/patient‐out‐pocket‐spending‐medicare‐2016‐17/data (viewed Mar 2024).

- 12. Australian Medical Association. Non‐PBS medications driving patient out‐of‐pocket costs [media release]. September 26, 2019. https://www.ama.com.au/media/non‐pbs‐medications‐driving‐patient‐out‐pocket‐costs (viewed July 2022).

- 13. Ghinea N. The increasing costs of medicines and their implications for patients, physicians and the health system. Intern Med J 2024; 54: 545‐550.

- 14. Ghinea N. The Medicines Repurposing Program — a critical perspective. Aust Health Rev 2024; 48: 259‐261.

- 15. IQVIA. Global use of medicines 2023: outlook to 2027 [website]. IQVIA, 2023. https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the‐iqvia‐institute/reports/the‐global‐use‐of‐medicines‐2023 (viewed July 2024).

- 16. Department of Health and Aged Care. PBS Expenditure and Prescriptions Report 1 July 2021 to 30 June 2022 (expenditure table 5a) [website]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/expenditure‐prescriptions/pbs‐expenditure‐and‐prescriptions‐report‐1‐july‐2021‐to‐30‐june‐2022 (viewed Jan 2024).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Macquarie University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Macquarie University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This work is supported by a Macquarie University Research Fellowship. The funder had no role in the planning, writing or preparation of this manuscript.

No relevant disclosures.