Homelessness in Australia has increased substantially in the past decade, with women constituting 44.1% of the 122 494 people recorded as homeless in 2021.1 Of these women, 50.7% are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and 37.8% are aged 55 years and older.1 Moreover, these census statistics are conservative: 381 168 people sought assistance from specialist homelessness services across Australia in 2022–23, with female participants making up almost two‐thirds (62.9%).2

Homelessness includes visible rough sleeping (eg, in streets, parks, cars), couch surfing and accommodation in refuges, crisis and transitional accommodation and dwellings below minimum community standards. In a “cycle of perpetual vulnerability”,3 women who are homeless are at a high risk of violence, sexual assault, exploitation and theft, and trauma is cumulative and compounded. These vulnerabilities, along with other social determinants of health relating to housing and material circumstances, lead to negative health impacts, as well as affecting engagement with the health system.4

The importance of prevention and identifying individuals at risk

Within the health care system, prevention, early identification and intervention are key to positive individual outcomes,5 including for people experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness.6 Family and domestic violence is the most common driver of homelessness in Australia, accounting for 45% of homelessness service requests for assistance in 2022–23.2 Older women experiencing relationship breakdowns or financial insecurity are also acutely vulnerable.7 The dearth of affordable housing and rentals, compounded by the cost of living crisis, has seen homelessness and emergency relief services nationwide reporting unprecedented requests for help, including from women and families.8

Importantly, health sector workers should be mindful that people may not disclose their homelessness to health or other government services, and that the nomenclature of “no fixed address” under‐reports homelessness. Fear of stigma and judgement, shame, or the requirement to provide a postal address to access services are among common reasons for not disclosing homelessness.9 Women who are pregnant or who have children face additional barriers, as homelessness can be a red flag for child protection intervention or removal.10

Health of homeless women

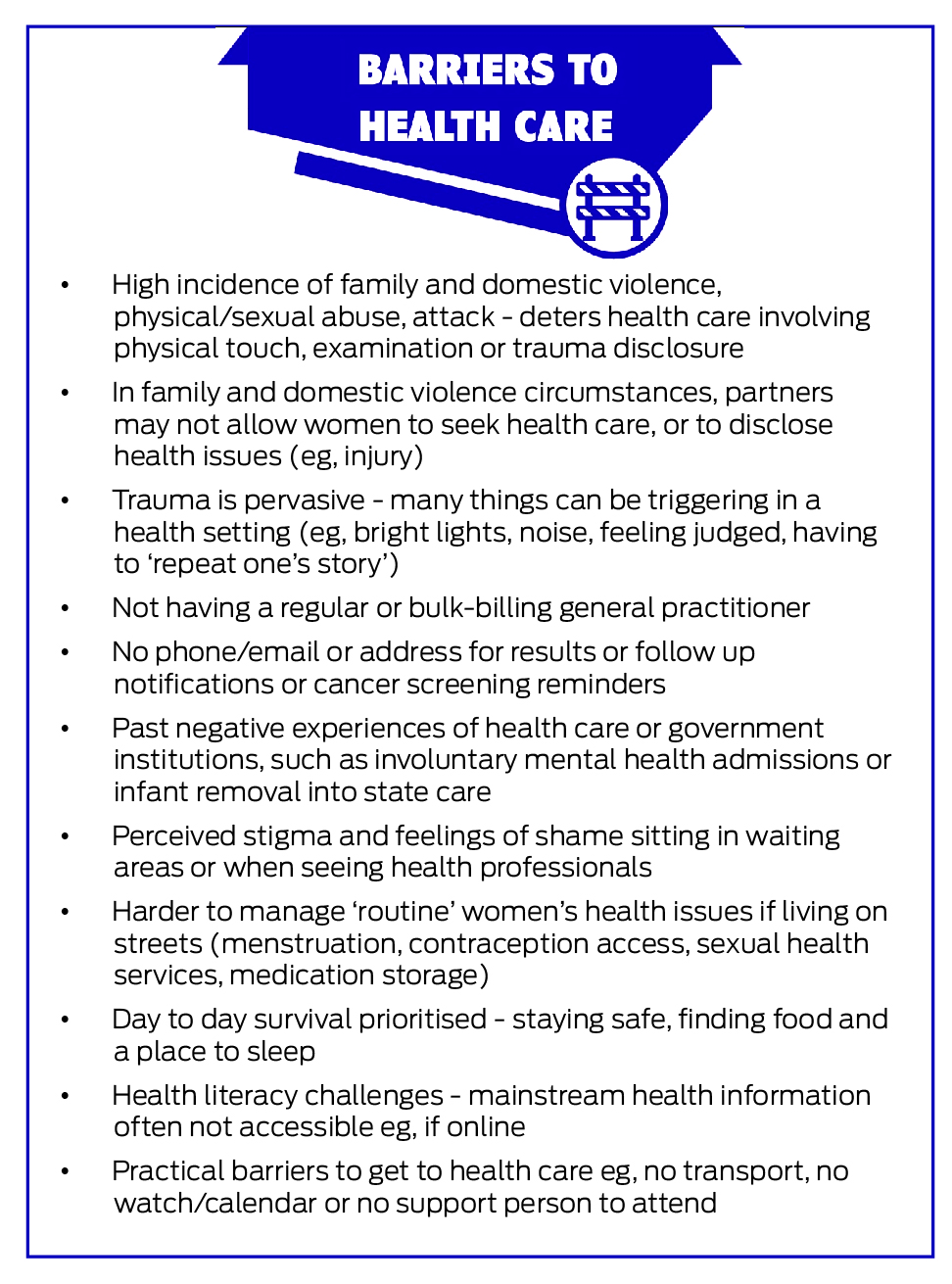

Homelessness is linked to significantly higher rates of both physical and mental health conditions irrespective of sex, including preventable chronic diseases.11 Multimorbidity is common,11 but significant barriers hinder health care access, engagement, primary care and prevention (Box 1).12 Trauma underlies many of these barriers,7,13 alongside practical barriers and the fundamental competing needs of survival and safety.14 This perpetuates a revolving hospital door, with higher emergency department use and unplanned admissions increasing the longer people remain homeless.9

For women experiencing homelessness, there are additional health vulnerabilities and barriers (Box 1). Our recent research showed homelessness being associated with a life expectancy gap of around three decades compared to the overall population,15 but the gap is almost four decades for women who have experienced homelessness (median age at death 47 years [unpublished data]) compared with 85 years in the overall Australian female population.16

Women experiencing homelessness also face additional health challenges related to accessing appropriate and consistent sexual and reproductive health care, as well as antenatal and postnatal care,13,17 and trauma has a visceral effect on receptiveness to physical examinations and screening.18 Moreover, family and domestic violence contributes significantly to injury as a driver of female hospital use among this cohort.9

What can be done to reduce these health care barriers and disparities?

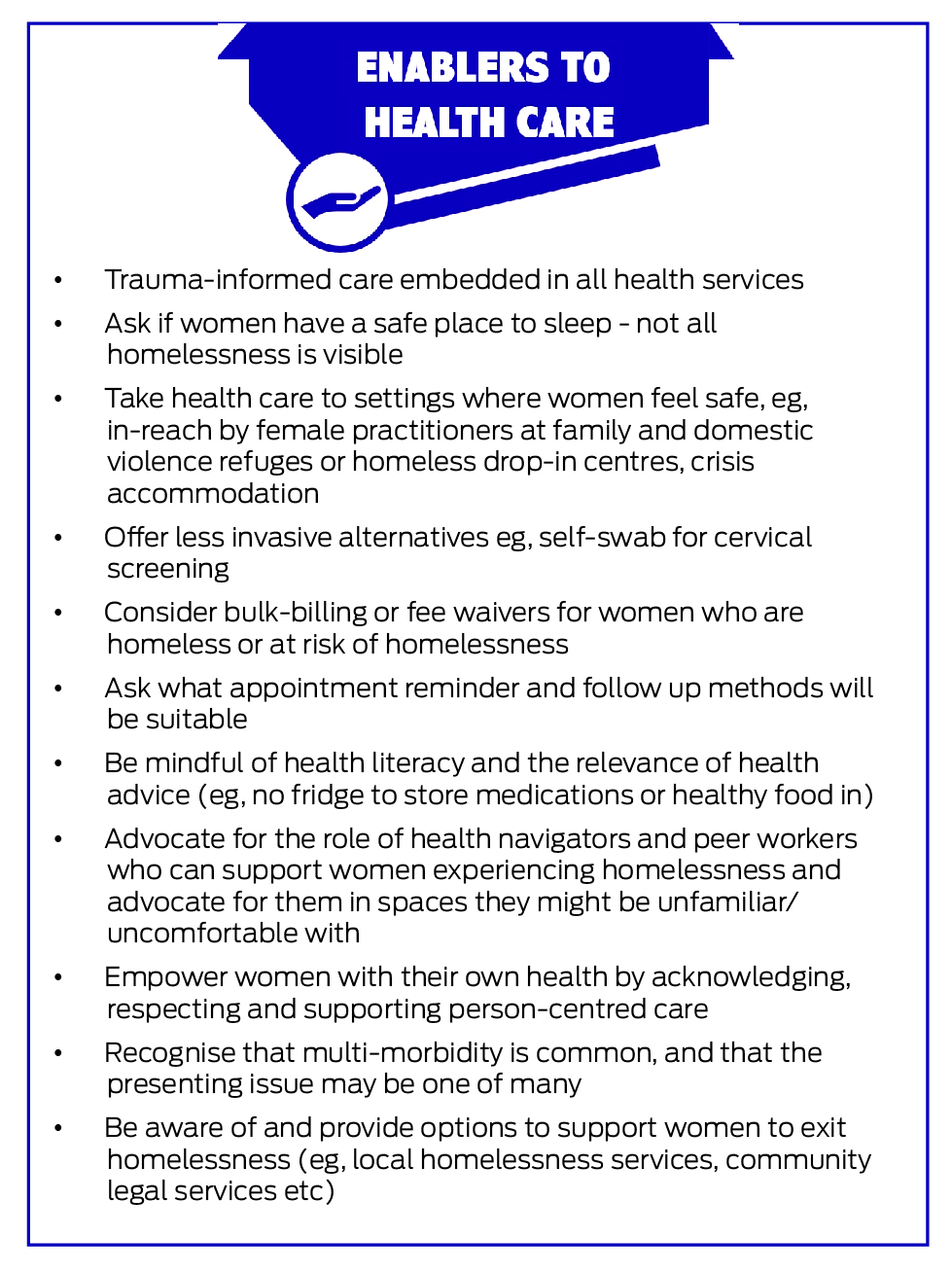

Rising rates of new and entrenched homelessness in Australia and the increasing proportion of women affected suggest that current responses are inadequate. Health and housing are fundamental human rights and without basic shelter, safety and security, it is extremely difficult to access health care or maintain good health and wellbeing. Although challenges such as affordable housing, supported accommodation and family and domestic violence prevention may be considered out of the health sector's scope of responsibility, health care providers can play an important role in advocating for and influencing change at a population level.19 Australian state, territory and federal governments have developed strategies and plans for the provision of safe and affordable housing to reduce homelessness, and health sector workers can contribute by responding to consultation opportunities and parliamentary submissions relating to homelessness and housing, and by encouraging their organisations to do the same. Patient advocacy is also needed at an individual level, and this is possible within all health care settings. Box 2 provides examples of tangible actions applicable for all health care settings. Given the role that stigma and trauma play as barriers to homeless women receiving care, recognising individuals’ needs and listening with empathy are vital starting points to improving their health.

Further, and particularly important given the disproportionate rate of homelessness in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, and recognising intergenerational homelessness and the ongoing impacts of colonisation, cultural safety and trauma‐informed care are essential. Involvement and acknowledgement of the expertise of Aboriginal controlled organisations and Aboriginal health workers is vital for health services committed to providing equitable care.

Multilevel action (policy, organisational and individual) is needed to reduce the health barriers and disparities faced by homeless women. However, from our combined experience working alongside this vulnerable population, for whom trauma is ubiquitous, the importance of recognising their resilience and listening with empathy and without judgement cannot be over‐stated if we are to walk together to reduce the enormous health barriers and disparities they face.

Provenance

Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Estimating homelessness: census [website]. Canberra, ABS; 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/estimating‐homelessness‐census/latest‐release (viewed June 2024).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Data tables: specialist homelessness services annual report 2022–23 [website]. Canberra: 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness‐services/specialist‐homelessness‐services‐annual‐report/data (viewed June 2024).

- 3. Li J, Urada L. Cycle of perpetual vulnerability for women facing homelessness near an urban library in a major US metropolitan area. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 5985.

- 4. Stafford A, Wood L. Tackling health disparities for people who are homeless? Start with social determinants. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017; 14: 1535.

- 5. AbdulRaheem Y. Unveiling the significance and challenges of integrating prevention levels in healthcare practice. J Prim Care Community Health 2023; 14: 21501319231186500.

- 6. Parsell C, Marston G. Beyond the ‘at risk’ individual: housing and the eradication of poverty to prevent homelessness. Aust J Public Adm 2012; 71(1): 33‐44.

- 7. Sutherland G, Bulsara C, Robinson S, Codde J. Older women's perceptions of the impact of homelessness on their health needs and their ability to access healthcare. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46: 62‐68.

- 8. Dunn S. Shelter WA pre‐budget submission (2023‐24) [website]. Perth, WA: Shelter WA; 16 Dec 2022. https://www.shelterwa.org.au/shelter‐wa‐pre‐budget‐submission‐2023‐24/ (viewed Apr 2024).

- 9. Wood L, Tuson M, Gazey A, et al. Royal Perth Hospital Homeless Team: third evaluation report. Fremantle, Western Australia: Institute for Health Research, University of Notre Dame Australia; 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/376268820_royal_perth_hospital_homeless_team_third_evaluation_report_november_2023 (viewed July 2024).

- 10. Wood L, Bogoias N. Accessing antenatal care when you are rough sleeping: barriers and enablers. Parity 2022 Sep 8; 35: 14‐16.

- 11. Vallesi S, Tuson M, Davies A, Wood L. Multimorbidity among people experiencing homelessness—insights from primary care data. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 6498.

- 12. Davies A, Wood LJ. Homeless health care: meeting the challenges of providing primary care. Med J Aust. 2018; 209: 230‐234. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/209/5/homeless‐health‐care‐meeting‐challenges‐providing‐primary‐care

- 13. Phipps M, Dalton L, Maxwell H, Cleary M. Women and homelessness, a complex multidimensional issue: findings from a scoping review. J Soc Distress Homeless 2019; 28: 1‐13.

- 14. Allen J, Vottero B. Experiences of homeless women in accessing health care in community‐based settings: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid Synth 2020; 18: 1970‐2010.

- 15. Tuson M, Vallesi S, Wood L. Tracking deaths of people who have experienced homelessness: a dynamic cohort study in an Australian city. BMJ Open 2024; 14: e081260.

- 16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Deaths in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2022. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life‐expectancy‐deaths/deaths‐in‐australia/contents/summary (viewed May 2024).

- 17. McGeough C, Walsh A, Clyne B. Barriers and facilitators perceived by women while homeless and pregnant in accessing antenatal and or postnatal healthcare: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Health Soc Care Community 2020; 28: 1380‐1393.

- 18. Kohler RE, Roncarati JS, Aguiar A, et al. Trauma and cervical cancer screening among women experiencing homelessness: a call for trauma‐informed care. Womens Health (Lond) 2021; 17: 17455065211029238.

- 19. Luft LM. The essential role of physician as advocate: how and why we pass it on. Can Med Educ J 2017; 8: e109.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Notre Dame Australia, as part of the Wiley – The University of Notre Dame Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

We acknowledge the research assistance of Cara Donnelly, Home2Health team, University of Notre Dame Australia.

No relevant disclosures.