The Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) is an independent rural general practice workforce and training program fully funded by the Department of Health and Aged Care since 2000. It is operationally delivered by the Remote Vocational Training Scheme Ltd (a national training provider). This perspective article describes the RVTS and its development over time to lay the foundations for this supplement on Growing and sustaining doctors in rural, remote and First Nations communities, which shows the outcomes of the RVTS program.

The RVTS supports the delivery of vocational general practice and rural generalist training for the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) and/or the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM). In doing so, the RVTS regularly liaises with both general practice colleges to manage accreditation, training requirements, and examinations among other issues. However, the RVTS has a nuanced focus compared with other rural general practice vocational training pathways (Box 1).

First, the RVTS specifically aims to support vocational training in more remote locations classified as Modified Monash Model (MMM) 4–7 and rural Aboriginal Medical Services (AMS) (MMM2–7) through a Remote and an AMS Stream respectively.1 Second, although the ACRRM and the RACGP apply remote supervision selectively when they hope to expand the training in rural locations with limited supervisors,2,5 the RVTS fully uses remote supervision (ie, online and intermittent face‐to‐face) because of its context of supporting more isolated and remote doctors.3 Many RVTS registrars are in areas with major general practice workforce shortages and a high clinical workload, which function as barriers to sourcing local supervision.6,7

Third, the RVTS only enrols doctors who are already working in eligible rural and remote general practices or AMS as prevocational doctors with minimum level 3 or 4 supervision under the Australian Medical Council (ie, deemed able to work independently with remote supervision).3 This differs from wider rural general practice training models where doctors commonly move to a rural training practice to commence training, relative to the eligibility and accreditation requirements of various rural general practice training pathways.

Fourth, the RVTS has a specific requirement for the participating doctors to continue to work in the same practice (in the eligible location from where they applied for the RVTS) while completing the RVTS’ three‐to‐four years of practice‐based general practice training.3 If the doctors choose to move locations, they typically need to withdraw and re‐apply in subsequent rounds (note the RVTS has two intakes per year since 2022). This focus on continuity of work/retention in the same practice is unique among general practice training models, the latter usually involving registrars moving between practices and/or hospitals for diversity of experience.2,4 The retention‐focused training of the RVTS plays an important role in stemming the higher workforce turnover in locations where the RVTS operates.8,9 Primary care workforce turnover in remote locations affects patients and costs through lower value care, increased hospitalisations, and the direct and indirect costs of replacing staff.9,10,11 Halving remote workforce turnover and reducing the use of short term staff is projected to save $32 million annually in the Northern Territory alone.11

Finally, the RVTS period of three‐to‐four‐years of practice‐based training is longer than that provided through other general practice training models, which involve a year of hospital training and up to two years of practice‐based training.2,4 Further details about the RVTS program are described in the Supporting Information.3

Characteristics of the RVTS cohort

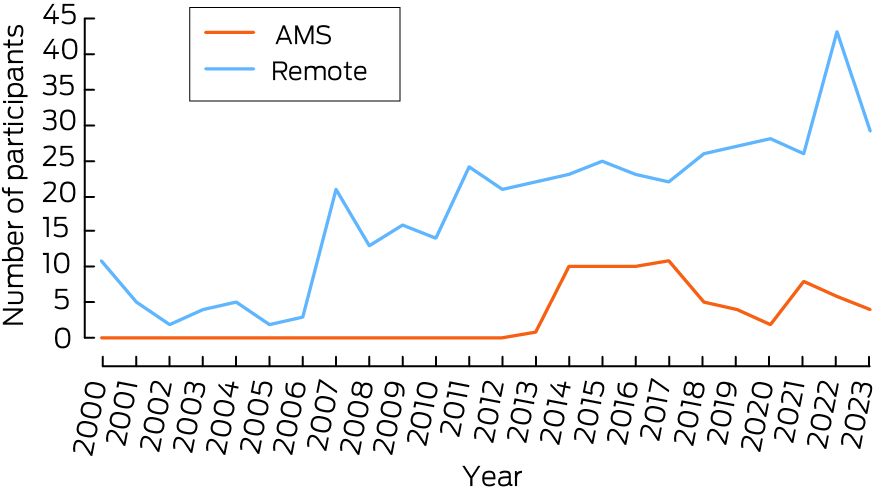

Box 2 presents data from the RVTS administrative dataset, showing the program has grown over time related to an incremental growth in funding. The RVTS commenced in 2000 as a pilot program with 11 doctors targeting MMM4–7 areas, increasing to an annual cohort of 22 Remote Stream places in 2013. The AMS Stream commenced in 2013 and included ten additional places per year mostly in AMSs in MMM2–7 areas. The total annual quota has been relatively stable at around 32 doctors since 2014, other than a once‐only surge in 2022 due to commencing an additional mid‐year intake process (to spread the operational workload across the year). In some years the AMS cohort did not reach ten places, mainly due to fewer applicants, and the Department of Health and Aged Care agreed for increased selection of Remote Stream candidates in such years. Occasionally, annual cohorts have been more than 32 when the Department of Health and Aged Care has agreed to additional enrolments as a suitable use of underspent funding.

Box 3 identifies that the RVTS reaches rural areas of all states and territories with reasonable parity to MMM4–7 and First Nations populations. The bulk of the Remote Stream participants has been based in the eastern states, where there are higher proportional MMM4–7 populations. However, the RVTS has the potential to weight its distribution to the states and territories with greater land sizes and sparsity of regional centres, such as the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia.

Box 4 shows that AMS Stream participants are mostly concentrated in MMM2–4 locations; in contrast, half of the Remote Stream participants are in MMM5 areas, with 82.7% in MMM5–7 locations and only 32.2% in coastal areas, showing the RVTS mostly supports inland communities.

Box 5 identifies that the number or participants matured to 506 by 2023; most are in the Remote Stream (86%), with both streams predominantly enrolling international medical graduates (IMGs). In the early cohorts, similar numbers of IMGs and Australian medical graduates were enrolled, but since 2013 the RVTS program has enrolled over 80% IMGs — a group that is relied upon for providing medical services in rural, remote and First Nations communities.12,13 Australian policy requires IMGs to work for up to ten years in distribution priority areas, which include rural and AMS services, to access Medicare provider numbers.14 As a group, IMGs have nuanced professional support and career development needs; they can be less satisfied under mandated rural work arrangements and more likely to turnover in rural practice.15,16,17,18,19

Box 5 also shows that IMGs and Australian medical graduates enter the RVTS with an average of five to six years of Australian clinical experience and a total average overall clinical experience of 14 years. The characteristics of the RVTS cohort, previous clinical experience and the challenges of general practice in rural, remote and First Nations communities means that a nuanced training and professional support model is needed. The supervision and support model needs to accommodate busy doctors who have access to limited staff, equipment, diagnostic tools and referral options and working in communities with distinct geographical, professional and social characteristics; involving caring for people on low incomes, with culturally safe medical services.7,20,21,22 Box 6 provides a high level overview of the RVTS’ supervision and support model, which is explained more by O'Sullivan and colleagues23 in this supplement.3

Drawing evidence from the RVTS

Although the RVTS has been operating since 2000 and its basic characteristics have been noted, its overall outcomes and the reasons why it might be effective have not been holistically described in the recent peer reviewed literature.24,25 This supplement aims to address this gap and summarise the results of an independent mixed methods evaluation of the RVTS which was led by the University of Queensland in 2023–2024. This supplement describes the results in four articles. These results have direct relevance for shaping the evidence base around solutions for a well distributed and sustainable general practice workforce for rural, remote and First Nations communities in Australia. Box 7 shows how the articles in this supplement help to inform current major national rural workforce strategies in Australia.26

In this supplement, McGrail and colleagues27 provide evidence of the continuity of service and longer term retention outcomes of the RVTS, drawing on 23 years’ registrar data linked with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency information about current practice location.

Following this, O'Sullivan and colleagues23 provide the first full description of the RVTS’ supervision and support model and how and why it is effective for addressing personal and professional support of this unique cohort. This article uses a realist evaluation that draws on theory and empirical data from interviews. It teases out what enables the RVTS doctors to feel professionally and non‐professionally supported when continuously working and training in challenging settings.

O'Sullivan and colleagues28 draw on focus groups and thematic analysis aiming to summarise the results of an emerging new strategy that the RVTS has been using since 2018 called the Targeted Recruitment Strategy. This strategy involves the RVTS working with communities and rural workforce stakeholders to decide priority locations and bundle tailored recruitment initiatives with the RVTS’ retention and training support. The aim is to attract more prevocational doctors to high need areas where they can access general practice vocational training and support through the RVTS.

Through interviews, O'Sullivan and colleagues29 explore stakeholder perspectives of the benefits of the RVTS, as an example of a place‐based retention‐focused general practice training program. This value is important to differentiate from more supply‐focused training models, such as the Australian General Practice Training Program (AGPT),33 which typically involve moving between hospital and various practices (Box 1). Further, it can usefully inform concepts such as the single‐employer model because it explores perceived benefits of registrars maintaining continuity of employer.31 Any data presented in the articles of this supplement are provided with ethics approval (The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee; Ref. 2023/HE001926; 24 October 2023).

In summary, the RVTS is a nuanced general practice training program that remotely supports and trains doctors already working in a challenging context, while aiming to promote the continuity of service to high needs communities. This supplement draws on insights from administrative data, interviews, focus groups, and theory, to provide unique evidence which can inform major national policies.

Box 1 – Key differences between the Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) and other rural general practice training1,2,3,4

|

RVTS |

Other rural general practice training models |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

More remote locations MMM4–7 and AMS MMM2–7 |

Any rural location MMM2–7, with ACRRM having a focus of 12 months minimum in MMM4–7, not specific to AMS |

||||||||||||||

|

Non‐vocationally registered doctors already employed in eligible practice before commencing and who have no less than level 3 or 4 supervision |

Most registrars move into the rural practice that meets requisite supervision requirements for the general practice pathway they are on |

||||||||||||||

|

Mostly uses a remote supervision and support model, as practices generally have limited capacity |

Mostly face‐to‐face supervision, with remote supervision models used selectively |

||||||||||||||

|

Continuity of service/retention — stay in same practice as the one when the doctor enrolled in the RVTS, while progressing towards fellowship |

Registrars typically move around |

||||||||||||||

|

Registrars complete the first year of general practice training (hospital component) as a part of their overall general practice role. RVTS provides 3–4 years of practice‐based training |

Registrars complete a year of hospital‐based training and then around two years of practice‐based training |

||||||||||||||

|

12 months’ advanced skills training can be done at any point in a hospital or the same community setting |

12 months’ advanced skills training can be done at any point in any hospital or community setting. |

||||||||||||||

|

Fellowship of ACRRM and/or RACGP, including the general practice or rural generalist fellowship |

Registrars pursue ACRRM or RACGP fellowship including rural generalist fellowship |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AMS = Aboriginal Medical Services; ACRRM = Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine; MMM = Modified Monash Model; RACGP = Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – The Remote Vocational Training Scheme participants over time (n = 506)

AMS = Aboriginal Medical Services. The AMS Stream commenced in 2013. A mid‐year intake commenced in 2022 which brought enrolments for 2023 forward. The data source is the program's deidentified administrative dataset.

Box 3 – Distribution of Remote and Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS) Stream Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) participants by state1

|

State or territory |

Remote Stream: RVTS locations, n (%) |

Proportion of population (MMM4–7) |

AMS Stream: RVTS locations, n (%) |

Proportion of First Nations population* |

Overall land size (‘000 km2) |

Number of regional centres ≥ 50 000† |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

New South Wales |

182 (41.9%) |

32% |

15 (21%) |

34% |

801 |

8 |

|||||||||

|

Queensland |

119 (27.4%) |

22% |

27 (38%) |

29% |

1730 |

9 |

|||||||||

|

Victoria |

38 (8.8%) |

21% |

18 (25%) |

8% |

227 |

5 |

|||||||||

|

Western Australia |

41 (9.4%) |

10% |

4 (6%) |

11% |

2527 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Northern Territory |

27 (6.2%) |

3% |

4 (6%) |

8% |

1348 |

0 |

|||||||||

|

Tasmania |

15 (3,5%) |

3% |

1 (1%) |

4% |

68 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

South Australia |

12 (2.8%) |

9% |

2 (3%) |

5% |

984 |

0 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

MMM = Modified Monash Model. * First Nations population does not add to 100% because the Australian Capital Territory is not included, it has no eligible RVTS sites. † Regional centres were counted as ≥ 50 000 population excludes capital cities of states and territories. One Remote Stream candidate was in Papua New Guinea. The data source is the program's deidentified administrative dataset. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Distribution of Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) participants by Remote and Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS) Streams1

|

Rurality |

Remote (n = 434) |

AMS (n = 71) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

MMM1 |

1 (0.2%) |

8 (11.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

MMM2 |

5 (1.2%) |

16 (22.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

MMM3 |

3 (0.7%) |

16 (22.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

MMM4 |

66 (15.2%) |

15 (21.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

MMM5 |

218 (50.2%) |

7 (9.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

MMM6 |

68 (15.7%) |

4 (5.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

MMM7 |

73 (16.8%) |

5 (7.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Coastal (within 50 km of coast) |

140 (32.2%) |

42 (59.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

MMM = Modified Monash Model. AMS Stream placements were temporarily eligible in MMM1. Initially, MMM1 was eligible within the AMS Stream, MMM2–7 only from 2019. A small number of MMM1–3 locations were deemed eligible in the Remote Stream through special consideration. The data source is the program's deidentified administrative dataset. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Characteristics of the commencing participants 2000–2023

|

Characteristic |

Result (IMGs*) |

Result (AMGs) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of commencing participants |

373 |

133 |

|||||||||||||

|

Training stream (n, %) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Remote |

319/435 (73.3%) |

116/435 (26.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

AMS |

54/71 (76.1%) |

17/71 (23.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex, male (n, %) |

247 (66.6%) |

81 (60.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Age, years (median, IQR) |

40 (35–45) |

36 (32–43) |

|||||||||||||

|

Australian work experience, years (median, IQR) |

5 (3–8) |

6 (4–11) |

|||||||||||||

|

Overall clinical experience, years (median, IQR) |

14 (10–19.5) |

6 (4–11) |

|||||||||||||

|

IMGs (n, %) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Entry 2000–2012 |

75/141 (53.2%) |

na |

|||||||||||||

|

Entry 2013–2020 |

205/249 (82.3%) |

na |

|||||||||||||

|

Entry 2021–2023 |

93/116 (80.2%) |

na |

|||||||||||||

|

IMG region of origin: Asia, Middle East or Africa (n, %) |

313 (84.1%) |

na |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AMG = Australian Medical Graduate; AMS = Aboriginal Medical Services; IMG = international medical graduate; IQR = interquartile range. * Moratoriums require IMGs to work in Distribution Priority Areas for ten years to access Medicare provider numbers14 and regardless, all doctors on the Remote Vocational Training Scheme, including AMGs, are required to stay in the eligible community where they applied, to access the program.3 The data source is the program's deidentified administrative dataset. First Nations doctors were not identified in the dataset. In the IMG cohort, two were missing data about sex which changed the IMG denominator to 371 for the sex calculation. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – The Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) supervision and support model3

- The RVTS program uses a model of remote supervision mostly with one continuous supervisor employed in another practice (and different community).

- Supervisors are mostly experienced rural general practitioners/rural generalists, familiar with both the RVTS program (many past participants and international medical graduates) and knowledgeable of the participant's location.

- Structured online webinars and workshops are delivered outside of work hours.

- Other activities include regular in‐practice teaching and workplace‐based assessment by experienced supervisors and medical educators as well as asynchronous online learning resources.

- Support is enhanced through the provision of tools, methods, and training to facilitate and enhance productive, safe, and high quality services by confident, comfortable doctors despite being a more isolated cohort.

More information is described in the Supporting Information and by O'Sullivan et al23 in this supplement.

Box 7 – Alignment of the Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) to selected major rural medical workforce strategies in Australia

|

Major strategies |

RVTS program evidence helps inform |

Additional information (references) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

National Medical Workforce Strategy26 |

How to promote distribution of sustainable general practice workforce for rural, remote and First Nations communities |

||||||||||||||

|

Independent review of regulatory settings30 |

How to effectively support rural international medical graduate doctors when they are working under regulatory conditions |

||||||||||||||

|

Single employer model31 |

The benefits of training continuously as a general practitioner in the same rural practice |

||||||||||||||

|

Closing the Gap32 |

How to expand continuity of rural general practice services in Aboriginal medical services and rural areas where there is a high proportion of First Nations peoples |

||||||||||||||

|

Australian General Practice Training Program33 |

Mature remote supervision and support model for doctors in general practice vocational training, working in areas of high need that have limited supervisors and professional and personal supports |

||||||||||||||

|

Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report34 |

Access to sustainable, equitable, continuity of care across the primary health care system |

||||||||||||||

|

Digital Health Blueprint and Action Plan35 |

A sustainable learning health system for rural and remote and First Nations community settings using digital innovation |

||||||||||||||

|

Independent Scope of Practice Review36 |

How to unleash rural and remote general practice workforce capacity through sustainable support and retention of doctors within multidisciplinary teams; remaining in the same community enables doctors contributing to up‐skilling other staff and service quality improvements |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Department of Health and Aged Care. The Modified Monash Model. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/health‐workforce/health‐workforce‐classifications/modified‐monash‐model (viewed Aug 2024).

- 2. Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine. Training handbooks and guides. Brisbane: ACRRM, 2024. https://www.acrrm.org.au/resources/training/handbooks‐guides (viewed Aug 2024).

- 3. Remote Vocational Training Scheme. Training Program. Albury: RVTS, 2023. https://www.rvts.org.au/rvts‐training‐program/ (viewed Aug 2024).

- 4. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. AGPT registrar training handbook. Melbourne: RACGP, 2024. https://www.racgp.org.au/education/gp‐training/gp‐training/education‐policy‐and‐supporting‐documents/program‐handbooks‐and‐guidance‐documents/agpt‐registrar‐training‐handbook (viewed Aug 2024).

- 5. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Remote Supervision Program, 2024. Melbourne: RACGP, 2024. https://www.racgp.org.au/education/gp‐training/remote‐supervision‐1/remote‐supervision‐program (viewed Aug 2024).

- 6. O'Sullivan B, Martin P, Taylor C, et al. Developing supervision capacity for training rural generalist doctors in small towns in Victoria. Rural Remote Health 2022; 22: 7124.

- 7. McGrail MR, Humphreys JS, Joyce CM, et al. How do rural GPs’ workloads and work activities differ with community size compared with metropolitan practice? Aust J Prim Health 2012; 18: 228–233.

- 8. McGrail MR, Humphreys JS. Geographical mobility of general practitioners in rural Australia. Med J Aust 2015; 203: 92–97. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/203/2/geographical‐mobility‐general‐practitioners‐rural‐australia#:~:text=A%20total%20of%20133%20GPs,82%25%20in%20very%20remote%20areas

- 9. Russell DJ, Wakerman J, Humphreys JS. What is a reasonable length of employment for health workers in Australian rural and remote primary healthcare services? Aust Health Rev 2013; 37: 256–261.

- 10. Ralston A, Fielding A, Holliday E, et al. “Low‐value” clinical care in general practice: a cross‐sectional analysis of low‐value care in early‐career GPs’ practice. Int J Qual Health Care 2023; 35: 0. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzad081

- 11. Zhao Y, Russell DJ, Guthridge S, et al. Costs and effects of higher turnover of nurses and Aboriginal health practitioners and higher use of short‐term nurses in remote Australian primary care services: an observational cohort study. BMJ Open 2019; 9: e023906.

- 12. O'Sullivan B, Russell DJ, McGrail MR, Scott A. Reviewing reliance on overseas‐trained doctors in rural Australia and planning for self‐sufficiency: applying 10 years’ MABEL evidence. Hum Resour Health 2019; 17: 8.

- 13. Gilles MT, Wakerman J, Durey A. “If it wasn't for OTDs, there would be no AMS”: overseas‐trained doctors working in rural and remote Aboriginal health settings. Aust Health Rev 2008; 32: 655–663.

- 14. Department of Health and Aged Care. 10‐Year moratorium and scaling. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/doctors‐and‐specialists/what‐we‐do/19ab/moratorium#the‐10year‐moratorium (viewed Aug 2024).

- 15. Kehoe A, McLachlan J, Metcalf J, et al. Supporting international medical graduates’ transition to their host‐country: realist synthesis. Med Educ 2016; 50: 1015–1032.

- 16. Yoemans N, Chowdhury A, Roberts A. International medical graduates (IMGs) in cul‐de‐sacs: “lost in the labyrinth” revisited? Med J Aust 2022; 216: 553–555. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/11/international‐medical‐graduates‐imgs‐cul‐de‐sacs‐lost‐labyrinth‐revisited

- 17. McGrath P, Henderson D, Tamargo J, Holewa HA. Doctor–patient communication issues for International Medical Graduates: research findings from Australia. Educ Health 2012; 25: 48–54.

- 18. McGrail M, Humphreys J, Joyce C, Scott A. International medical graduates mandated to practise in rural Australia are highly unsatisfied: Results from a national survey of doctors. Health Policy 2012; 108: 133–139.

- 19. Russell D, Humphreys J, McGrail M, et al. The value of survival analyses for evidence‐based rural medical workforce planning. Hum Resour Health 2013; 11: 65.

- 20. Wakerman J. Defining remote health. Aust J Rural Health 2004; 12: 210–214.

- 21. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote health [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural‐remote‐australians/rural‐and‐remote‐health (viewed Aug 2024).

- 22. Bourke L, Sheridan C, Russell U, et al. Developing a conceptual understanding of rural health practice. Aust J Rural Health 2004; 12: 181–186.

- 23. O'Sullivan B, Giddings P, Gurney R, et al. Holistic support framework for doctors training as rural and remote general practitioners: a realist evaluation of the RVTS model. Med J Aust 2024; 221 (Suppl): S16–S22.

- 24. Wearne S, Giddings P, McLaren J, Gargan C. Where are they now? The career paths of the Remote Vocational Training Scheme registrars. Aust Fam Physician 2010; 39: 53–56.

- 25. Wearne S. General practice supervision at a distance — is it remotely possible? Aust Fam Physician 2005; 34: 31–33.

- 26. Department of Health and Aged Care. National Medical Workforce Strategy 2021–2031. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/national‐medical‐workforce‐strategy‐2021‐2031 (viewed Aug 2024).

- 27. McGrail M, O'Sullivan B, Giddings P. Continuity of service and longer term retention of doctors training as general practitioners in the Remote Vocational Training Scheme. Med J Aust 2024; 221 (Suppl): S9–S15.

- 28. O'Sullivan B, Veeraja U, Gurney R, Giddings P. Recruitment and retention of new doctors in remote and Aboriginal medical services through the Remote Vocational Training Scheme's Targeted Recruitment Strategy: a focus group study. Med J Aust 2024; 221 (Suppl): S23–S28.

- 29. O'Sullivan B, Giddings P, McGrail M. Perceived stakeholder benefits of continuously training general practitioners in the same rural or remote practice: interviews exploring the Remote Vocational Training Scheme. Med J Aust 2024; 221 (Suppl): S29–S34.

- 30. Kruk R. Independent review of Australia's regulatory settings relating to overseas health practitioners final report. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Finance, 2023. https://www.regulatoryreform.gov.au/priorities/health‐practitioner‐regulatory‐settings‐review (viewed Aug 2024).

- 31. Department of Health. Single employer model pilot. Hobart: Tasmanian Government, 2024. https://www.health.tas.gov.au/single‐employer‐model‐infrastructure‐grants (viewed Aug 2024).

- 32. Department of Health and Aged Care. National key performance indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health/reporting/nkpis (viewed Aug 2024).

- 33. Department of Health and Aged Care. Australian General Practice Training (AGPT) Program. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/australian‐general‐practice‐training‐agpt‐program (viewed Aug 2024).

- 34. Department of Health and Aged Care. Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/strengthening‐medicare‐taskforce‐report?language=en (viewed Aug 2024).

- 35. Department of Health and Aged Care. The digital health blueprint and action plan 2023–2033. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/the‐digital‐health‐blueprint‐and‐action‐plan‐2023‐2033?language=en (viewed Aug 2024).

- 36. Department of Health and Aged Care. Unleashing the potential of our health workforce — scope of practice review. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024 https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/scope‐of‐practice‐review (viewed Aug 2024).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

The Remote Vocational Training Scheme is supported by funding from the Australian Government. Executive and senior leaders at the Rural Doctors Association of Australia, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, General Practice Supervision Australia, General Practice Registrars Australia, NSW Rural Doctors Network and individuals, including Jennifer May (University of Newcastle) and Susan Wearne (Australian National University), contributed insights through a Stakeholder Advisory Group. Others, including Ronda Gurney, Clara Smith and Veeraja Uppal (Remote Vocational Training Scheme management team), along with Tiana Gurney (The University of Queensland), contributed to data collection and interpretation of the findings.

The researchers were engaged by the RVTS through funds from the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. The funder was involved in the project reference group, but we worked independently.