The known: More than one in ten people hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction are re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge.

The new: In NSW, 42.3% of re‐admissions to hospital after acute myocardial infarction admissions during 2015–2020 were not to the initial treating hospital. Several factors influenced the likelihood of non‐index hospital admissions, including remoteness and the mixture of public and private health care. For people from regional and remote areas, non‐index hospital re‐admissions were associated with lower 30‐day mortality.

The implications: Our results are reassuring for people in regional and remote areas with acute myocardial infarction for whom returning to the specialised hospitals where they initially received treatment can be difficult.

Rates of re‐admission during the first 30 days after discharge from hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction are high (11–14%).1 People may return to the hospital from which they were discharged (the index hospital), or to a different hospital because of health system factors, such as the geographic location and mix of public and private hospitals.2,3,4 Re‐admissions after surgery to non‐index hospitals have been associated with higher mortality,2,5 but the few reports on their impact on outcomes for people hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction in the United States have yielded conflicting results.6,7 Further, these studies did not investigate two key factors relevant to Australia: a geographically highly dispersed population with specialist hospital services concentrated in major cities; and the provision of specialist services by both public and private hospitals.8 The combination of these two factors could result in a large proportion of non‐index hospital re‐admissions after hospitalisations with acute myocardial infarction, and the consequences could differ between people in major cities and those in regional or remote areas.

Awareness of geographic differences is essential for assessing the effects of differential access to specialised care on re‐admission patterns and mortality risk, especially for people in regional and remote areas. We therefore examined the frequency of and mortality outcomes for re‐admissions to non‐index hospitals within 30 days of hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction in New South Wales, with the aim of identifying factors associated with non‐index hospital re‐admissions, and differences between people residing in major cities or in regional or remote areas.

Methods

New South Wales covers more than 800 000 km2 and has about eight million residents, 75% of whom live in major cities.9 Hospital care is provided by 221 public and 210 private hospitals; private hospitals are focused on elective procedures, and generally do not have emergency departments.8

For our retrospective cohort study we analysed linked person‐level hospital admissions (Admitted Patient Data Collection)10 and mortality data (Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages) for NSW residents. The Admitted Patient Data Collection includes diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases and Related Problems, tenth revision, Australian modification (ICD‐10‐AM).11 The NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (https://www.cherel.org.au/about‐us) performed probabilistic data linkage, with an estimated false positive rate of 0.5%.12

Index hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction

We included records for all hospital admissions of adults (18 years or older) with primary diagnoses of acute myocardial infarction (ICD‐10‐AM codes I21.0– I21.9) during 1 January 2005 – 31 December 2020. Multiple hospital admissions within a 30‐day period were treated as a single hospital stay; if admissions with same‐day discharge dates or coded as ending in transfers were followed by another acute admission within 24 hours, the admissions were treated as a single hospital stay. The index hospital was defined as the hospital from which the patient was discharged to non‐acute care at the end of the index hospital admission. If a person was hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction several times within 30 days, the first hospitalisation was treated as the index admission, and the subsequent hospitalisations as re‐admissions.

30‐day re‐admissions

We identified all emergency re‐admissions within 30 days of discharge from the index acute myocardial infarction hospitalisation; only the first re‐admission was included in our analysis. The hospital where the person first received care during the re‐admission was recorded as the re‐admission hospital. A non‐index re‐admission hospital was defined as any other than the index hospital.

Outcomes and data definitions

The primary outcomes were 30‐day and 12‐month mortality, defined as deaths within 30 days or twelve months of hospital re‐admission. The two time points were selected as short and long term outcomes, encompassing both the immediate and ongoing health effects of re‐admission to non‐index hospitals.

For the index hospitalisation, we extracted information on age at admission, sex, myocardial infarction type (ST‐elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], ICD‐10‐AM codes I21.0–I21.3; non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI], ICD‐10‐AM code I21.4; or unspecified myocardial infarction, ICD‐10‐AM code I21.9), coronary revascularisation procedure (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI] or coronary artery bypass graft [CABG] surgery), emergency admission status, interhospital transfer during the index admission, hospital length of stay, other medical conditions (diagnosis codes recorded during the index hospitalisation and any hospitalisation during the two preceding years; Supporting Information, table 1), private health insurance status, socio‐economic status (Socio‐Economic Index for Areas [SEIFA] Index of Relative Socio‐economic Disadvantage [IRSD] quintile13 by residential Statistical Area level 2 [SA2]), and hospital type (public or private). Public hospitals were assigned to three hospital categories according to the NSW peer group classification:14 principal referral, large public (major hospitals, district group, community hospitals), or other public (Supporting Information, table 2). Private hospitals are not included in the NSW peer group classification and were assigned to a separate hospital category. Remoteness of residence (by SA2) was classified according to the Australian Statistical Geography Standard remoteness structure,15 grouped into two categories: major cities, and regional or remote areas.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the proportion of people re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge from hospitalisations with acute myocardial infarction who were re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals. We assessed the statistical significance of differences between index and non‐index hospital re‐admissions in patient and hospital characteristics, stratified by remoteness category in two‐sample Student t or Mann–Whitney U tests (continuous variables) or χ2 tests (categorical variables).

We assessed associations of re‐admission to non‐index hospitals with various factors in multiple logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, and selected other medical conditions, stratified by remoteness category.

For our analysis of the influence of re‐admission to non‐index hospitals on mortality outcomes, we accounted for factors that might confound associations by applying inverse probability weighting, a propensity score analysis method that estimates the probability of an exposure (here: non‐index re‐admission) based on the study covariates, and assigns weights to each patient that are inversely proportional to the estimated probabilities.16 We then assessed associations between non‐index hospital re‐admission and 30‐day and 12‐month mortality using multiple logistic regression, with and without inverse probability weighting and stratified by remoteness category. We report adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 16.1.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (2019/ETH00436).

Results

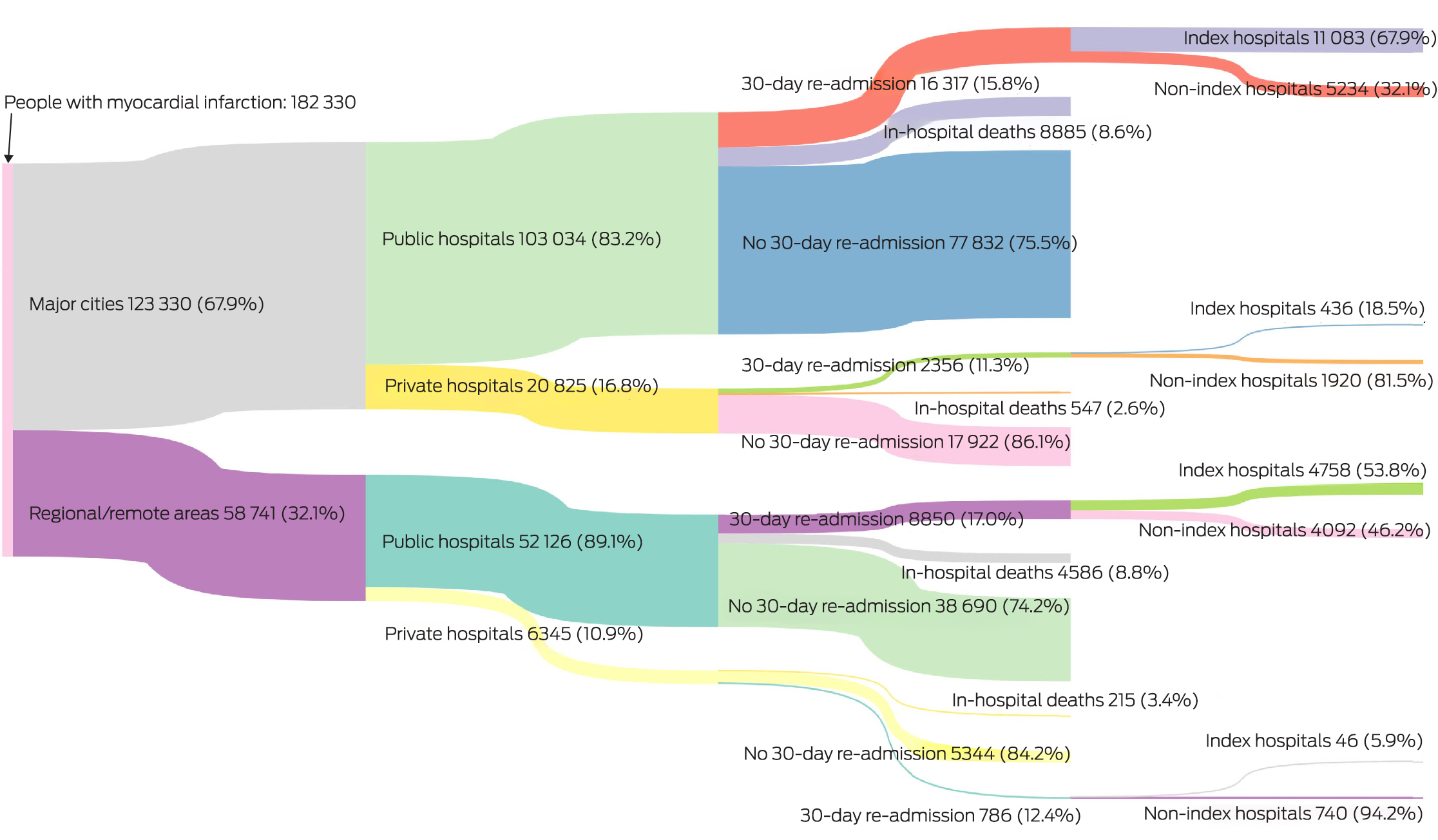

A total of 182 330 index admissions of people with acute myocardial infarction were recorded in NSW during 2005–2020: 123 859 of people from major cities (67.9%) and 58 471 from regional or remote areas (32.1%) (Box 1; Supporting Information, table 3). Of the 168 097 people who survived their index hospitalisations, 28 309 were re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge (16.8%), including 11 986 to non‐index hospitals (42.3% of re‐admissions): 7154 of 18 673 re‐admissions of people from major cities were to non‐index hospitals (38.3%), and 4832 of 9636 people from regional or remote areas (50.1%). The proportion of non‐index hospital re‐admissions was larger for people discharged from private hospitals than from public hospitals (major cities: 1920 of 2356, 81.5% v 5234 of 16 317, 32.1%; regional/remote areas: 740 of 786, 94.2% v 4092 of 8850, 46.2%) (Box 1).

Non‐index hospital re‐admission proportions by index admission characteristics

The mean age at the index admission was lower for people re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals (70.2 years; standard deviation [SD], 13.9 years) than for those re‐admitted to index hospitals (74.1 years; SD, 13.9 years); the proportion of women was smaller (36.1% v 40.6%), and the proportions with private health insurance (30.7% v 19.5%) or private hospital index admissions (22.2% v 3.0%) were larger. The proportion of emergency index admissions was smaller for people re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals (56.6% v 86.7%) and that of interhospital transfers larger (59.6% v 18.0%); their median index hospital length of stay was longer (6 days; interquartile range [IQR], 3–13 days v 5 days; IQR, 3–9 days). The proportions of patients with STEMI (28.8% v 23.1%) or who underwent CABG (10.6% v 4.5%) or PCI (23.7% v 20.0%) during the index admission were larger for people who were re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals than for those re‐admitted to index hospitals; the proportions with most other medical conditions were smaller (Box 2). The differences between non‐index and index hospital re‐admissions were greater for people from regional or remote areas than for those from major cities (Supporting Information, table 4).

The non‐index hospital re‐admissions proportion for people whose index admissions were to principal referral public hospitals was smaller for those from major cities (3491 of 11 544, 30.2%) than for people from regional or remote areas (1451 of 1652, 87.8%). The non‐index hospital re‐admissions proportion for people whose index admissions were to other (smaller) public hospitals was larger for those from major cities (713 of 1339, 53.2%) than for people from regional or remote areas (1056 of 3248, 32.5%). The non‐index hospital re‐admissions proportions for people whose index admissions were to private hospitals were large, both for people from major cities (1832 of 2356, 77.8%) and those from regional or remote areas (740 of 786, 94.1%); for people from major cities, 1066 of these re‐admissions (58.1%) were to principal referral hospitals, while 400 of those for people from regional or remote areas (54.0%) were to large public hospitals (Box 3).

Non‐index hospital re‐admissions: multivariate analyses

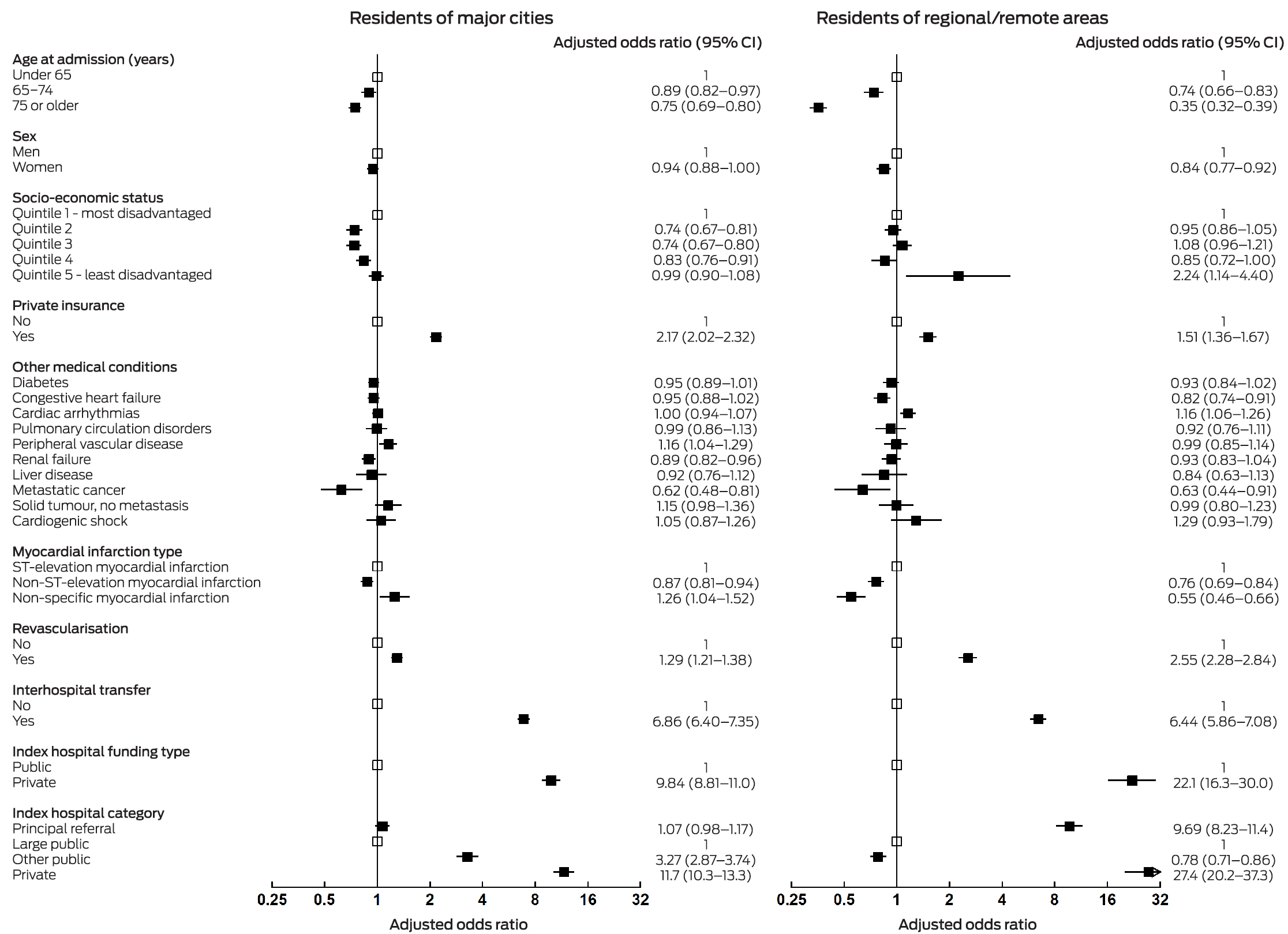

Among the 28 309 people re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of hospitalisations with acute myocardial infarction, the odds of being re‐admitted to a non‐index hospital were higher for those with private health insurance or private hospital index admissions, and for people who were transferred between hospitals or had undergone revascularisation during the initial hospitalisation; the odds were lower for people over 65 years of age, women, people residing in areas of lower socio‐economic disadvantage, and those with metastatic cancer or NSTEMI. The magnitude of some differences varied by remoteness category. For example, the odds of non‐index hospital re‐admission following a private hospital index admission were larger for people in regional or remote areas (aOR, 22.1; 95% CI, 16.3–30.0) than for residents of major cities (aOR, 9.84; 95% CI, 8.81–11.0), as were the odds of non‐index hospital re‐admission for people who had undergone revascularisation (aOR, 2.55 [95% CI, 2.28–2.84] v 1.29 [95% CI, 1.21–1.38]). The odds of non‐index hospital re‐admission for people with private health insurance were greater for residents of major cities (aOR, 2.17; 95% CI, 2.02–2.32) than for those in regional or remote areas (aOR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.36–1.67) (Box 4).

After inverse probability weighting adjustment for potential confounders, non‐index hospital re‐admission did not influence 30‐day mortality among people from major cities (aOR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.99–1.20), but it was associated with reduced mortality for people from regional or remote areas (aOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70–0.95). Twelve‐month mortality was also negatively associated with non‐index hospital re‐admission of people from regional or remote areas (aOR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81–0.96), but not those from major cities (aOR, 0.98, 95% CI, 0.93–1.03). Logistic regression models without inverse probability weighting yielded similar results (Box 5).

Discussion

During 2005–2020, 42.3% of people re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge from admissions with acute myocardial infarction returned to hospitals other than the discharging (index) hospital; the proportion was larger for people from regional or remote areas (50.1%) than for major city residents (38.3%). The distribution of re‐admission destinations varied by index hospital category and residential remoteness. Non‐index hospital re‐admissions were more likely for people who had STEMI, were transferred between hospitals or underwent revascularisation during the initial hospitalisation, were admitted to private hospitals for the initial admission, were under 65 years of age, or had private health insurance. Finally, 30‐day mortality was lower for people from regional or remote areas re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals, but not for people from major cities.

The 30‐day re‐admission rate for NSW people hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction during 2005–2020 was 16.8%, similar to values reported by other Australian and overseas studies.1,7,17,18 However, the proportion of non‐index hospital re‐admissions was much larger than in other studies; two recent United States studies reported values of 25%6 and 27%.7 Two factors that may explain the larger proportion in Australia are its geography and the combination of public and private hospitals serving different roles.8,9

We found that non‐index hospital re‐admissions were more likely for people with private health insurance, whereas in the United States the odds were higher for Medicare‐ or Medicaid‐subsidised patients than for those with other insurers.6 The difference probably reflects structural differences between the two health systems; private hospitals in the United States generally offer a full range of emergency and specialist care, but Australian private hospitals focus on elective procedures and most do not have emergency departments. Although Australians with private health insurance can opt for private hospital care, an emergency re‐admission to the same private facility is unlikely. As a result, the proportion of non‐index hospital re‐admissions in our study was extremely high for people discharged from private index hospitals, both in major cities (80.8%) and in regional or remote areas (94.1%).

As interhospital transfers are a frequent feature of acute myocardial infarction care pathways (United States: 17.1% of admissions;7 our study: 37.8%), it is important that investigators state how transfers are handled in their analyses. In one American study,7 transfer to the index hospital was associated with non‐index hospital re‐admission, as in our study; a second study6 did not report how interhospital transfers were handled. Similarly, one American study7 found that distance from the index hospital was a significant factor in non‐index hospital re‐admissions; the second6 did not specifically examine the question.

We found that the re‐admission destination for people who had been hospitalised with acute myocardial infarction was influenced by where they lived. In major cities, more than 80% of people discharged from principal referral or large public hospitals were re‐admitted to the same hospital or another principal referral hospital. Conversely, only 17% of people from regional or remote areas discharged from principal referral hospitals were re‐admitted to a similar level hospital. As the proportion of patients transferred between hospitals during the index admission was larger for those from regional or remote areas, they presumably received advanced treatment at a higher level facility during the index admission but attended a local, more convenient hospital when re‐admission was needed.

We also found that people aged 65 years or older and those with certain medical conditions (including diabetes, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and metastatic cancer) were less likely to be re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals. This could be because they were not transferred to higher level hospitals during the index admissions, and were therefore more likely to return to the same hospital for re‐admission. Important differences between residents of major cities and those of regional or remote areas in care and outcomes were also noted. For instance, only 18.3% of patients from regional or remote areas received PCI during the initial hospitalisation, compared with 30.5% of those from major cities. Further, higher in‐hospital mortality among people from regional and remote areas (8.2% v 7.6%) might reflect the selection of people at greater risk of death, as they are more likely to die in a centre unable to offer continuous PCI, or they might be deemed unsuitable for transfer to metropolitan centres for PCI or CABG.

We found that the relationship between non‐index hospital re‐admissions and 30‐day mortality for people re‐admitted after hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction is complex. Thirty‐day mortality was not significantly influenced by re‐admission to non‐index hospitals for people from major cities, but was significantly lower for those from regional or remote areas. One of the United States studies7 found no significant association between non‐index hospital re‐admission and 30‐day mortality, overall or stratified by distance from the index hospital, but the other6 found it was associated with significantly higher in‐hospital mortality. Differences in patient populations, sample sizes, and methods may explain the differences in findings. The association of reduced 30‐day mortality risk with non‐index hospital re‐admission in our study might be related to transfers of relatively less ill patients to specialised facilities for PCI or CABG procedures.

Limitations

We used a large population‐based dataset and employed robust statistical methods to reduce bias and improve the generalisability of our findings. Nevertheless, findings based on routinely collected data have limitations. The Admitted Patient Data Collection is an administrative database, the accuracy and completeness of which may be affected by variations in coding practices between clinical coders and health care facilities.19 Although we included a broad range of patient‐ and hospital‐level factors in our multivariable models, confounding by unmeasured covariates that influence mortality is possible. For example, we found that people from regional or remote areas who were under 65 years of age or had fewer other medical conditions were more likely to be transferred and treated in principal referral hospitals, and to undergo revascularisation. Despite controlling for confounding by inverse propensity matching, these people may have had a survival advantage compared with people treated in local hospitals. Further, the impact of changes in NSW hospital infrastructure during 2005–2020 was not assessed.

Conclusions

We found that 16.8% of people admitted to NSW hospitals with acute myocardial infarction during 2005–2020 were re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of their initial admission, and that 42.3% of re‐admissions were to hospitals other than the original hospital. Non‐index hospital re‐admissions were more likely for people who were under 65 years of age, had STEMI, had private health insurance, were transferred between hospitals or underwent revascularisation during their initial admission, or were admitted to private hospitals for their initial hospitalisation. Thirty‐ and 12‐month mortality was lower for people from regional or remote areas re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals. A prospective study could elucidate the complex health care interactions that influence outcomes for people with acute myocardial infarction.

Box 1 – Outcomes for 182 330 people hospitalised with myocardial infarction in New South Wales, 2005–2020, by remoteness category*

* Remoteness category defined according to the Australian Statistical Geography Standard Remoteness structure.15 30‐day re‐admission rates are based on number of people discharged alive from their index admissions. “Index hospital” is the discharging hospital for the initial hospitalisation with myocardial infarction; “non‐index hospital” is any other hospital.

Box 2 – Characteristics of people re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge from hospitalisations with acute myocardial infarction, New South Wales, 2005–2020

|

Characteristic |

Index hospital re‐admissions* |

Non‐index hospital re‐admissions |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

30‐day re‐admissions |

16 323 (57.7%) |

11 986 (42.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Index admission |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Acute myocardial infarction type |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

ST‐elevation myocardial infarction |

3765 (23.1%) |

3453 (28.8%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Non‐ST‐elevation myocardial infarction |

11 874 (72.7%) |

8040 (67.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Non‐specific myocardial infarction |

684 (4.2%) |

493 (4.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Coronary revascularisation |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Percutaneous coronary intervention |

3259 (20.0%) |

2844 (23.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery |

729 (4.5%) |

1270 (10.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Emergency admission |

14 160 (86.7%) |

6783 (56.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Interhospital transfer |

2940 (18.0%) |

7141 (59.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

5 (3–9) |

6 (3–13) |

|||||||||||||

|

Age (years), mean (SD) |

74.1 (13.9) |

70.2 (13.9) |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex (women) |

6633 (40.6%) |

4332 (36.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Index of Relative Socio‐economic Disadvantage |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Quintile 1 (most disadvantaged) |

4496 (27.5%) |

3766 (31.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Quintile 2 |

3568 (21.9%) |

2598 (21.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Quintile 3 |

3424 (21.0%) |

2337 (19.5%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Quintile 4 |

2542 (15.6%) |

1644 (13.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Quintile 5 (least disadvantaged) |

2288 (14.0%) |

1640 (13.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Private insurance |

3186 (19.5%) |

3675 (30.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other medical conditions |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Diabetes |

5740 (35.2%) |

3916 (32.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Congestive heart failure |

5702 (34.9%) |

3508 (29.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Cardiac arrhythmias |

6663 (40.8%) |

4599 (38.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Pulmonary circulation disorders |

920 (5.6%) |

580 (4.8%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Peripheral vascular disease |

1428 (8.7%) |

1038 (8.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Renal failure |

3792 (23.2%) |

2258 (18.8%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Liver disease |

385 (2.4%) |

276 (2.3%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Metastatic cancer |

392 (2.4%) |

194 (1.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Solid tumour, no metastasis |

904 (5.5%) |

597 (5.0%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Cardiogenic shock |

386 (2.4%) |

289 (2.4%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Discharging hospital type |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Public |

15 841 (97.0%) |

9326 (77.8%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Private |

482 (3.0%) |

2660 (22.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Discharging hospital category |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Principal referral |

8201 (50.2%) |

4995 (41.7%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Large public |

4763 (29.2%) |

2504 (20.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Other public |

2803 (17.2%) |

1784 (14.9%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Private |

482 (3.0%) |

2660 (22.2%) |

|||||||||||||

|

After the index admission |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

30‐day re‐admission: length of stay (days), median (IQR) |

4 (1–8) |

3 (1–8) |

|||||||||||||

|

Deaths, 30 days |

1974 (12.1%) |

1027 (8.6%) |

|||||||||||||

|

Deaths, 12 months |

5058 (31.0%) |

2644 (22.1%) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IQR = interquartile range, SD = standard deviation. * Based on discharging hospital for index acute myocardial infarction hospitalisation. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – 30‐day re‐admission destination by hospital category of index acute myocardial infarction hospitalisation and patient residential remoteness category*

|

|

|

|

|

Re‐admitted to non‐index hospitals, by type |

|||||||||||

|

Index discharging hospital location/type† |

Index admissions |

30‐day re‐admissions |

Re‐admitted to index hospitals |

Principal referral |

Large public |

Other public |

Private |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Major cities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Principal referral |

76 604 |

11 544 (16.4%) |

8001 (69.6%) |

1319 (11.5%) |

1386 (12.1%) |

628 (5.5%) |

158 (1.4%) |

||||||||

|

Large public |

18 532 |

3326 (19.9%) |

2399 (72.2%) |

699 (21.0%) |

51 (1.5%) |

142 (4.3%) |

34 (1.0%) |

||||||||

|

Other public |

7190 |

1339 (21.3%) |

611 (46.1%) |

494 (37.3%) |

148 (11.2%) |

42 (3.2%) |

29 (2.2%) |

||||||||

|

Private |

20 825 |

2356 (11.6%) |

436 (19.2%) |

1066 (47.0%) |

469 (20.7%) |

195 (8.6%) |

102 (4.5%) |

||||||||

|

Regional/remote areas |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Principal referral |

12 064 |

1652 (14.4%) |

200 (12.1%) |

87 (5.3%) |

635 (38.5%) |

714 (43.2%) |

15 (0.9%) |

||||||||

|

Large public |

23 159 |

3941 (18.5%) |

2364 (60.0%) |

316 (8.0%) |

198 (5.0%) |

1034 (26.3%) |

27 (0.7%) |

||||||||

|

Other public |

16855 |

3248 (22.2%) |

2192 (67.5%) |

221 (6.8%) |

557 (17.1%) |

251 (7.7%) |

27 (0.8%) |

||||||||

|

Private |

6345 |

786 (12.8%) |

46 (5.9%) |

60 (7.6%) |

400 (50.9%) |

262 (33.3%) |

18 (2.3%) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* The numbers of re‐admissions by index and non‐index hospital do not add to the total numbers of re‐admissions in some rows because information about the re‐admission hospital category was missing in the dataset for 47 re‐admissions. † Public hospitals were categorised based on peer group classification.14 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Non‐index hospital re‐admissions within 30 days of hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction, by residential remoteness category: multivariate analyses*

* Adjusted for age, sex, and other medical conditions. The values for both remoteness categories combined are included in the Supporting Information, table 5.

Box 5 – Associations between non‐index hospital re‐admissions within 30 days of hospitalisation with acute myocardial infarction and 30‐day and 12‐month mortality: multivariate analyses, with and without inverse probability weighting*

|

|

|

Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

|||||||||||||

|

Outcome |

Number of deaths |

Without inverse probability weighting |

With inverse probability weighting |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

30‐day mortality |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Overall |

3522 |

0.97 (0.88–1.06) |

1.00 (0.92–1.08) |

||||||||||||

|

Major cities |

2313 |

1.08 (0.96–1.21) |

1.09 (0.99–1.20) |

||||||||||||

|

Regional/remote areas |

1209 |

0.78 (0.66–0.93) |

0.81 (0.70–0.95) |

||||||||||||

|

12‐month mortality |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Overall |

7744 |

0.89 (0.83–0.95) |

0.95 (0.91–0.99) |

||||||||||||

|

Major cities |

5153 |

0.93 (0.85–1.02) |

0.98 (0.93–1.03) |

||||||||||||

|

Regional/remote areas |

2591 |

0.79 (0.70–0.90) |

0.88 (0.81–0.96) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CI = confidence interval. * Adjusted for age, sex, myocardial infarction type, revascularisation, interhospital transfer, emergency admission, socio‐economic status, residential remoteness category, private insurance, other medical conditions, and hospital category. Love plots of the standardised differences in covariates between index and non‐index hospital re‐admissions before and after propensity score matching are included in the Supporting Information, figures 1 to 3. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 12 September 2023, accepted 15 January 2024

- Md Shajedur Rahman Shawon1

- Jennifer Yu2,3

- Art Sedrakyan4

- Sze‐Yuan Ooi5

- Louisa Jorm1

- 1 Centre for Big Data Research in Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Prince of Wales Hospital and Community Health Services, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Eastern Heart Clinic Pty Ltd, Sydney, NSW

- 4 Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, United States of America

- 5 Prince of Wales Hospital, Sydney, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by University of New South Wales, as part of the Wiley – University of New South Wales agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data sharing:

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Wang H, Zhao T, Wei X, et al. The prevalence of 30‐day readmission after acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Cardiol 2019; 42: 889‐898.

- 2. Brooke BS, Goodney PP, Kraiss LW, et al. Readmission destination and risk of mortality after major surgery: an observational cohort study. Lancet 2015; 386: 884‐895.

- 3. Havens JM, Olufajo OA, Tsai TC, et al. Hospital factors associated with care discontinuity following emergency general surgery. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 242‐249.

- 4. Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Care fragmentation in the postdischarge period: surgical readmissions, distance of travel, and postoperative mortality. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 59‐64.

- 5. Snow K, Galaviz K, Turbow S. Patient outcomes following interhospital care fragmentation: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2020; 35: 1550‐1558.

- 6. Sakowitz S, Madrigal J, Williamson C, et al. Care fragmentation after hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2023; 187: 131‐137.

- 7. Rymer JA, Chen AY, Thomas L, et al. Readmissions after acute myocardial infarction: how often do patients return to the discharging hospital? J Am Heart Assoc 2019; 8: e012059.

- 8. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's hospitals at a glance. Updated 18 July 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/australias‐hospitals‐at‐a‐glance/contents/summary (viewed July 2024).

- 9. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Regional population. Statistics about the population and components of change (births, deaths, migration) for Australia's capital cities and regions, 2022–23. 26 Mar 2024. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional‐population/latest‐release. (viewed July 2023).

- 10. Centre for Health Record Linkage (NSW Health). Datasets. 2024. https://www.cherel.org.au/datasets (viewed July 2024).

- 11. Innes K, Hooper J, Bramley M, DahDah P. Creation of a clinical classification. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision, Australian modification (ICD‐10‐AM). Health Inf Manag 1997; 27: 31‐38.

- 12. Boyd JH, Randall SM, Ferrante AM, et al. Accuracy and completeness of patient pathways: the benefits of national data linkage in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; 15: 312.

- 13. Australian Bureau of Statistics. IRSD. In: Census of Population and Housing: Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016 (2033.0.55.001). 27 Mar 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~IRSD~19 (viewed July 2024).

- 14. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian hospital peer groups (cat. no. HSE 170). 16 Nov 2015. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/australian‐hospital‐peer‐groups/summary (viewed Nov 2023).

- 15. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Remoteness structure. Australian Statistical Geography Standard (ASGS), edition 3, July 2021 – June 2026. 20 July 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/statistical‐geography/remoteness‐structure (viewed Nov 2023).

- 16. Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res 2011; 46: 399‐424.

- 17. Bureau of Health Information. Exploring clinical variation in readmission. Return to acute care following discharge from hospital, eight clinical conditions, NSW, July 2012 – June 2015. 12 Apr 2017. https://www.bhi.nsw.gov.au/BHI_reports/readmission/clinical‐variation‐in‐readmission (viewed Nov 2023).

- 18. Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Killian JM, et al. Thirty‐day rehospitalizations after acute myocardial infarction: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157: 11‐18.

- 19. Lujic S, Watson DE, Randall DA, et al. Variation in the recording of common health conditions in routine hospital data: study using linked survey and administrative data in New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e005768.

Abstract

Objectives: To examine the frequency of re‐admissions to non‐index hospitals (hospitals other than the initial discharging hospital) within 30 days of admission with acute myocardial infarction in New South Wales; to examine the relationship between non‐index hospital re‐admissions and 30‐day mortality.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study; analysis of hospital admissions (Admitted Patient Data Collection) and mortality data (Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages).

Setting, participants: Adults admitted to NSW hospitals with acute myocardial infarction re‐admitted to any hospital within 30 days of discharge from the initial hospitalisation, 1 January 2005 – 31 December 2020.

Main outcome measures: Proportion of re‐admissions within 30 days of discharge to non‐index hospitals, and associations of non‐index hospital re‐admissions with demographic and initial hospitalisation characteristics and with 30‐day and 12‐month mortality, each by residential remoteness category.

Results: Of 168 097 people with acute myocardial infarction discharged alive, 28 309 (16.8%) were re‐admitted to hospital within 30 days of discharge, including 11 986 to non‐index hospitals (42.3%); the proportion was larger for people from regional or remote areas (50.1%) than for people from major cities (38.3%). The odds of non‐index hospital re‐admission were higher for people with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction, for people whose index admissions were to private hospitals, who were transferred between hospitals or had undergone revascularisation during the initial admission, were under 65 years of age, or had private health insurance; the influence of these factors was generally larger for people from regional or remote areas than for those from large cities. After adjustment for potential confounders, non‐index hospital re‐admission did not influence mortality among people from major cities (30‐day: adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99–1.20; 12‐month: aOR, 0.98, 95% CI, 0.93–1.03), but was associated with reduced mortality for people from regional or remote areas (30‐day: aOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.70–0.95; 12‐month: aOR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.81–0.96).

Conclusions: The geographically dispersed Australian population and the mixed public and private provision of specialist services means that re‐admission to a non‐index hospital can be unavoidable for people with acute myocardial infarction who are initially transferred to specialised facilities. Non‐index hospital re‐admission is associated with better mortality outcomes for people from regional or remote areas.