Babies born with weights outside the healthy range (2500–4500 g) are at greater risk of illness, poor development, perinatal death, and poorer health in adulthood.1 As the proportion of healthy birthweight babies is smaller for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous) than non‐Indigenous babies (in 2017: 89.0% v 94.0%),2 the National Agreement on Closing the Gap target 2 (CGT‐2) is that 91% of Indigenous babies are born with a healthy birthweight by 2031.3

The Productivity Commission monitors progress towards Closing the Gap goals, including national and jurisdictional trends in the birthweight of Indigenous babies.4 Estimation of the healthy birthweight proportion for CTG‐2 is based solely on the Indigenous status of the babies,2 but about 30% of Indigenous babies are born to non‐Indigenous mothers; these babies have better neonatal outcomes, including healthy birthweight, than Indigenous babies born to Indigenous mothers.5

Improving neonatal outcomes, including healthy birthweight, is primarily influenced by reducing social and health disadvantages for the mother, particularly during the antenatal period.6 Moreover, interventions for improving neonatal outcomes must be centred on mothers as the primary recipients. Consequently, analyses based solely on the Indigenous status of the babies could statistically reduce the difference between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous people in healthy birthweight proportions, thereby obscuring disparities and diverting attention from questions of equity. We therefore examined differences in healthy birthweight for Indigenous babies born to Indigenous and non‐Indigenous mothers, and their impact on CTG‐2 progress assessment.

For our retrospective observational study, we analysed data in the Queensland Perinatal Data Collection (QPDC),7 a population‐based cross‐sectional data collection, for singleton babies born alive during 1 January 2011 – 31 December 2020. The QPDC determines the Indigenous status of babies and mothers by asking all mothers, according to the guideline in the Are you of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin? pamphlet.7 We estimated the proportions of babies with healthy birthweight by year in four groups: Indigenous babies born to non‐Indigenous mothers, Indigenous babies born to Indigenous mothers, all Indigenous babies, and non‐Indigenous babies born to non‐Indigenous mothers. For each group, we used fractional polynomial regression to determine the mean proportion across the study period. We also examined the association between the mother's Indigenous status and healthy birthweight for Indigenous babies in a subsample of Indigenous babies for whom information for all covariates included in a logistic regression model was available (39 122 of 46 987, 83%) (further details: Supporting Information, part 1). The study was approved by the Queensland Health Metro North Health Human Research Ethics Committee, (HREC/2021/QRBW/70547) and by Research Ethics and Integrity at the University of Queensland (2021/HE000721). We report our study according to the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.8

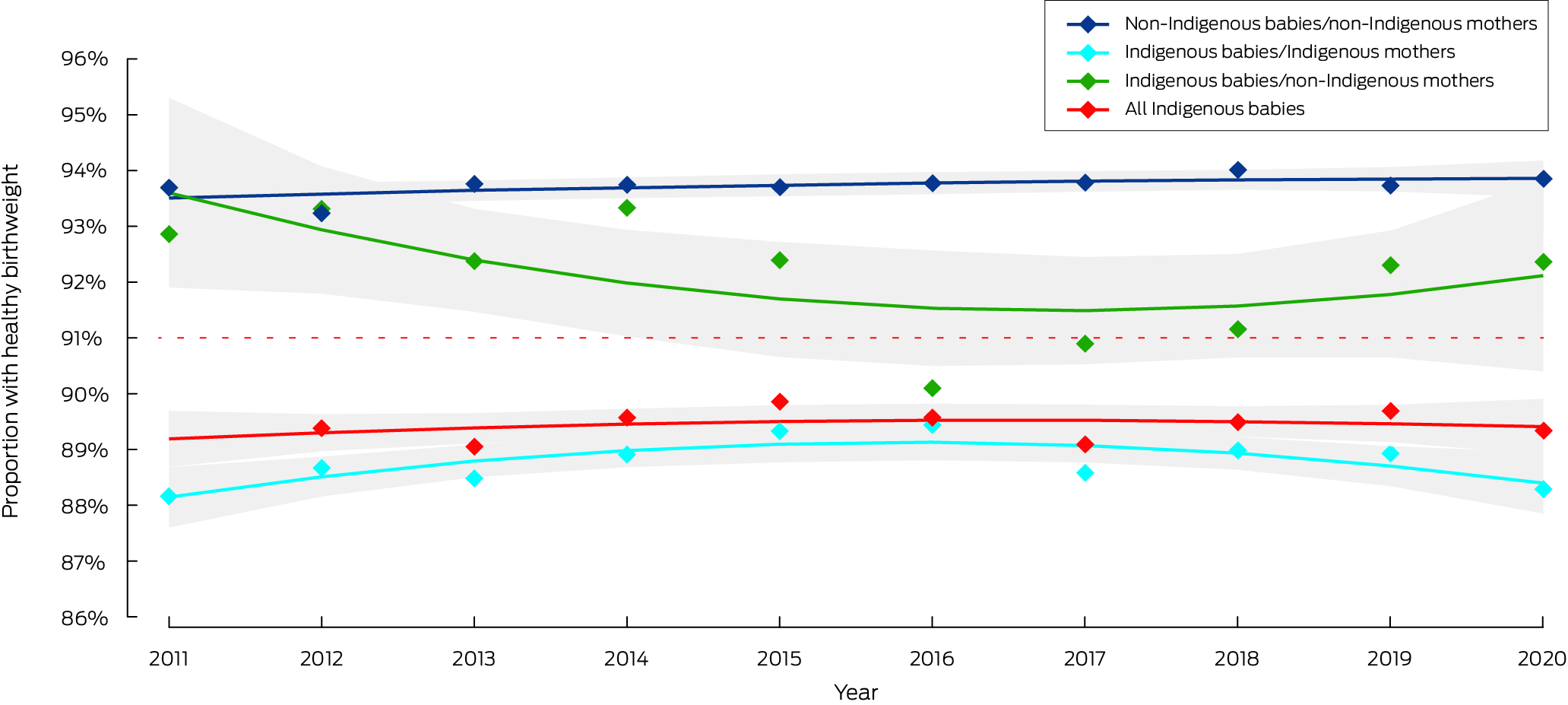

The QPDC included Indigenous status and birthweight data for 587 996 singleton babies born alive during 2011–2020, 46 987 of whom were Indigenous (8%); 37 538 were born to Indigenous mothers (79.9%) and 9449 to non‐Indigenous mothers (20.1%). (Supporting Information, figure 1 and table 2). The proportion of babies with healthy birthweight was larger for Indigenous babies born to non‐Indigenous mothers (8691, 92.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI], (91.4–92.5%) than for those born to Indigenous mothers (33 321, 88.8%; 95% CI, 88.4–89.1%) (Supporting Information, table 3). In most years, the proportion of Indigenous babies born to non‐Indigenous mothers with healthy birthweight exceeded the CGT‐2 target of 91%, but the proportion of Indigenous babies born to Indigenous mothers was consistently below the target (Box). The association analysis indicated that Indigenous babies born to non‐Indigenous mothers are more likely to have healthy birthweight than those born to Indigenous mothers (odds ratio [OR], 1.41; 95% CI, 1.29–1.54; adjusted OR, 1.19, 95% CI, 1.09–1.32). Combining these two groups would therefore overestimate the healthy birthweight proportion for Indigenous babies, as also indicated by the fact that the proportion of Indigenous babies with healthy birthweight born to Indigenous mothers was consistently smaller than that for all Indigenous babies (Box).

Despite its large population‐based sample, one limitation of our study is the mother‐reported Indigenous status of babies and mothers. This might result in reporting bias, as some mothers may be reluctant to identify themselves and their babies as Indigenous.9 Further, the findings may not be generalisable to the whole of Australia, as only QPDC data were analysed.

Our analysis of Queensland perinatal data indicates that the current approach to assessing the healthy birthweight proportion on the basis of the babies’ Indigenous status alone overestimates the overall healthy birthweight proportion for Indigenous babies. This may diminish the focus on achieving equity and obscure differences in healthy birthweight proportions for Indigenous and non‐Indigenous babies. We recommend calculating the healthy birthweight proportion according to the Indigenous status of both the baby and their mother to better monitor progress toward achieving CGT‐2. This approach will provide a more accurate assessment of the healthy birthweight proportion and enable a comprehensive evaluation of the gap between Indigenous and non‐Indigenous people.

Box – Proportions of Indigenous and non‐Indigenous singleton live‐birth babies with healthy birthweight, Queensland, 2011–2020*

* The dots depict the actual proportions of babies with healthy birthweight, the lines the fitted curves with 95% confidence intervals (grey shaded areas). The dotted red line marks the 2031 target level for healthy birthweight for Indigenous babies.

Received 10 August 2023, accepted 28 March 2024

- 1. National Indigenous Australian Agency, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Tier 1: Health status and outcomes. Birthweight. In: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework. 14 June 2024. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1‐01‐birthweight (viewed July 2024).

- 2. Productivity Commission. Socio‐economic outcome area 2. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are born healthy and strong. Closing the Gap information repository, 2021. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard/se/outcome‐area2 (viewed July 2024).

- 3. The National Agreement. Closing the Gap targets and outcomes. July 2020. https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national‐agreement/targets (viewed Nov 2023).

- 4. Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap: annual data compilation report. July 2023. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/annual‐data‐report/report (viewed July 2024).

- 5. Kennedy B, Cornes S, Martyn S, et al. Measuring Indigenous perinatal outcomes: should we use the Indigenous status of the mother, father or baby. Health Statistics Centre, Queensland Health, Mar 2009. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/147223/techreport_2.pdf (viewed Nov 2023).

- 6. Blumenshine P, Egerter S, Barclay CJ, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2010; 39: 263‐272.

- 7. Queensland Health. Queensland Perinatal Data Collection (QPDC): manual 2019–2020, version 1.0.1. Collection Year. 2019. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0029/858431/qpdc‐manual‐1920‐v1.0.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 8. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007; 18: 805‐835.

- 9. Robertson H, Lumley J. How midwives identify women as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders. Aust Coll Midwives Inc J 1995; 8: 26‐29.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data sharing:

We do not have permission to share data. The data underlying this study can be obtained from the Statistical Services Branch, Department of Health, Queensland Health.

This study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1198495) and the Australian government through the Australian Research Council‐funded Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (CE200100025). The funders had no involvement in the planning, writing, or publication of the study, nor did they have any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, reporting, or publication of this article.

No relevant disclosures.