Clinical record

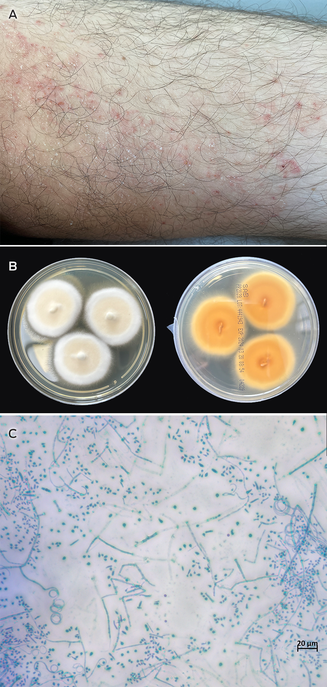

Patient 1, an otherwise well 25‐year‐old man presented with an itchy rash of 15 months duration on his groin and thighs, with no systemic symptoms (Box, A). He had arrived in Australia as a refugee from Afghanistan via Pakistan 12 months previously. He was twice prescribed terbinafine 1% cream and had also self‐medicated using topical clotrimazole and 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate with little benefit. In the past two months, he had been commenced on oral fluconazole 150 mg weekly by his general practitioner, with some improvement of the truncal rash but with persistence in the groin and thigh. A urease‐negative Trichophyton species was cultured from skin scrapings, which was referred to a reference laboratory for further identification (Box, B and C). Trichophyton indotineae was identified by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer region of the ribosomal DNA genes.1 Antifungal susceptibility testing showed a minimum inhibitory concentration to itraconazole of 0.06 mg/L (Supporting Information). Oral itraconazole was prescribed for eight weeks with significant improvement.

We have since isolated T. indotineae from another patient (Patient 2) from Sri Lanka at our refugee health clinic who has yet to commence treatment.

Discussion

Dermatophyte infections are common, affecting 20–25% of the population worldwide.2 The skin, hair and nails are the most frequently involved. The fungi causing infection (dermatophytes) rarely cause invasive disease, and infections are managed in the Australian outpatient setting, usually by general practitioners and dermatologists.

Trichophyton species cause the majority of dermatomycoses.2 Recently, difficult‐to‐treat cases of tinea corporis (body), cruris (groin and pubic region), and faciei (face), characterised by extensive, inflammatory plaques, have been reported, caused by a newly recognised species T. indotineae (previously T. mentagrophytes genotype VIII), which is frequently (up to 76%) terbinafine‐resistant.3,4,5 Large disease outbreaks were first described across the Indian subcontinent, but cases have now spread globally, including in patients with no travel history, highlighting local human‐to‐human transmission.5,6,7,8

Both our patients were migrants from countries in geographic proximity to India, which is one of the top ten destination countries for Australian residents returning from overseas.9 These data indicate the potential for further importation of this infection into Australia. Indeed, T. indotineae (labelled as the sexual stage, Arthroderma benhamiae), was first described in Australia in 2008, after identification of an isolate without accompanying clinical details.10 To our knowledge, there have been no other reports of T. indotineae infection from Australia.

The T. indotineae global outbreak has been attributed in part to the availability of topical antifungal preparations containing terbinafine in combination with potent corticosteroids such as clobetasol.5 In Australia, terbinafine is the recommended first line agent for topical and systemic treatment for all forms of tinea.11 Topical terbinafine is available without prescription in commercial pharmacies. Multiple surveys in aged care have shown inappropriate and increased use of topical antifungal agents with prolonged duration and as‐required prescriptions.12

Although the diagnosis of tinea is made clinically, these cases highlight the importance of a laboratory diagnosis by culture, to confirm the presence of infection and accurately identify the causative pathogen, especially in patients with treatment‐refractory infection. Trichophyton spp. and other dermatophytes are slow growing (two to four weeks), which can dissuade clinicians from requesting laboratory testing. However, culture‐based diagnosis remains the cornerstone of diagnosis. Definitive identification of the cultured isolate requires sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer region of the ribosomal DNA genes, available at a number of mycology reference laboratories.

Some Australian laboratories have transitioned to molecular polymerase chain reaction based testing, which affords a more rapid turnaround time and increased sensitivity.13 However, the most widely used assay (Dermatophytes and other Fungi, AusDiagnostics) cannot currently differentiate T. indotineae from other members of the T. mentagrophytes/T. interdigitale species complex. This highlights the complementary nature of culture and molecular‐based methods in fungal diagnostics. Culture also has the advantage of providing an isolate for susceptibility testing, which is not routinely undertaken in Australia as drug‐resistant dermatophyte infections have been rare. Currently, there are no defined clinical breakpoints to allow categorisation of “susceptible” or “resistant” or epidemiological cutoff values.6 Although we did not perform in vitro susceptibility tests for terbinafine, itraconazole is the drug of choice for treating T. indotineae infection.6 Sequencing of the squalene epoxidase gene (SQLE) involved in terbinafine resistance may offer an alternative testing approach.14

Overall, because of these limitations in laboratory diagnosis and the absence of local guidelines, there is likely to be an underdiagnosis of T. indotineae infection, and surveillance studies are required to document the frequency of the infection and its treatment outcomes in the Australian setting. Clinicians and laboratories should be aware of T. indotineae infection and be alert to its possibility in the event of poor clinical response to terbinafine to ensure accurate mycological investigation.

Lessons from practice

- Trichophyton indotineae is a novel, highly infectious and drug‐resistant fungus causing an epidemic of severe, extensive tinea infections that are difficult to treat. It has emerged from India and has now spread globally, including to Australia.

- T. indotineae isolates are often resistant to terbinafine in vitro, the recommended first line topical and systemic antifungal agent for treating Trichophyton infections in Australia.

- Clinicians should be aware of this new infection and collect skin scrapings for fungal microscopy and culture in patients with widespread tinea of the body, groin and face, or in patients where the infection has not responded to topical antifungal therapy, and should avoid prescribing topical corticosteroid treatment.

- Microbiology laboratories should be aware of the need to accurately identify T. indotineae and perform antifungal susceptibility testing where clinically indicated. Current commercial molecular methods for detection of dermatophytes do not discriminate T. indotineae from the T. mentagrophytes complex.

Box – Tinea cruris infection in Patient 1

A: Rash on the patient's thigh at presentation. B: Trichophyton indotineae culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar after ten days incubation at 30°C. Colonies are beige in colour with a white periphery, flat and granular (left); the reverse is light brown to yellow in colour (right). C: T. indotineae microscopic features (lactophenol cotton blue, 400x magnification), showing numerous spherical to pyriform microconidia together with spiral hyphae and occasional thin‐walled macroconidia.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Interpretive criteria for identification of bacteria and fungi by targeted DNA sequencing. 2nd ed. CLSI guideline MM18. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2018.

- 2. Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses 2008; 51 Suppl 4: 2‐15.

- 3. Kano R, Kimura U, Kakurai M, et al. Trichophyton indotineae sp. nov.: a new highly terbinafine‐resistant anthropophilic dermatophyte species. Mycopathologia 2020; 185: 947‐958.

- 4. Delliere S, Joannard B, Benderdouche M, et al. Emergence of difficult‐to‐treat tinea corporis caused by Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex isolates, Paris, France. Emerg Infect Dis 2022; 28: 224‐228.

- 5. Ebert A, Monod M, Salamin K, et al. Alarming India‐wide phenomenon of antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: A multicentre study. Mycoses 2020; 63: 717‐728.

- 6. Jabet A, Normand AC, Brun S, et al. Trichophyton indotineae, from epidemiology to therapeutic. J Mycol Med 2023; 33: 101383.

- 7. Canete‐Gibas CF, Mele J, Patterson HP, et al. Terbinafine‐resistant dermatophytes and the presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J Clin Microbiol 2023; 61: e0056223.

- 8. Chowdhary A, Singh A, Kaur A, Khurana A. The emergence and worldwide spread of the species Trichophyton indotineae causing difficult‐to‐treat dermatophytosis: a new challenge in the management of dermatophytosis. PLoS Pathog 2022; 18: e1010795.

- 9. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Overseas arrivals and departures, Australia. Resident returns – short‐term. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/industry/tourism‐and‐transport/overseas‐arrivals‐and‐departures‐australia/latest‐release#resident‐returns‐short‐term (viewed June 2024).

- 10. Kong F, Tong Z, Chen X, Sorrell T, et al. Rapid identification and differentiation of Trichophyton species, based on sequence polymorphisms of the ribosomal internal transcribed spacer regions, by rolling‐circle amplification. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46: 1192‐1199.

- 11. Therapeutic Guidelines. Therapeutic guidelines: Dermatology. 2022, https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au/guideLine?guidelinePage=Dermatology&frompage=etgcomplete (viewed Mar 2024).

- 12. Royal Melbourne Hospital and the National Centre for Antimicrobial Stewardship. Antimicrobial prescribing practice in Australian residential aged care facilities. Results of the 2020 Hospital National Antimicrobial Prescribing Survey Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care, 2023. https://www.amr.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐09/antimicrobial‐prescribing‐in‐australian‐residential‐aged‐care‐facilities‐results‐of‐the‐2020‐aged‐care‐national‐antimicrobial‐prescribing‐survey.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 13. Lin BB, Pattle N, Kelley P, Jaksic AS. Multiplex RT‐PCR provides improved diagnosis of skin and nail dermatophyte infections compared to microscopy and culture: a laboratory study and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2021; 101: 115413.

- 14. Kong X, Tang C, Singh A, et al. Antifungal susceptibility and mutations in the squalene epoxidase gene in dermatophytes of the Trichophyton mentagrophytes species complex. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021; 65: e0005621.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Patient consent:

The patient provided written consent for publication.

We thank the microbiology laboratory staff at Monash Pathology, and Rogan Lee from the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Laboratory Services, Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, New South Wales Health Pathology for his assistance with microscope photography.

No relevant disclosures.