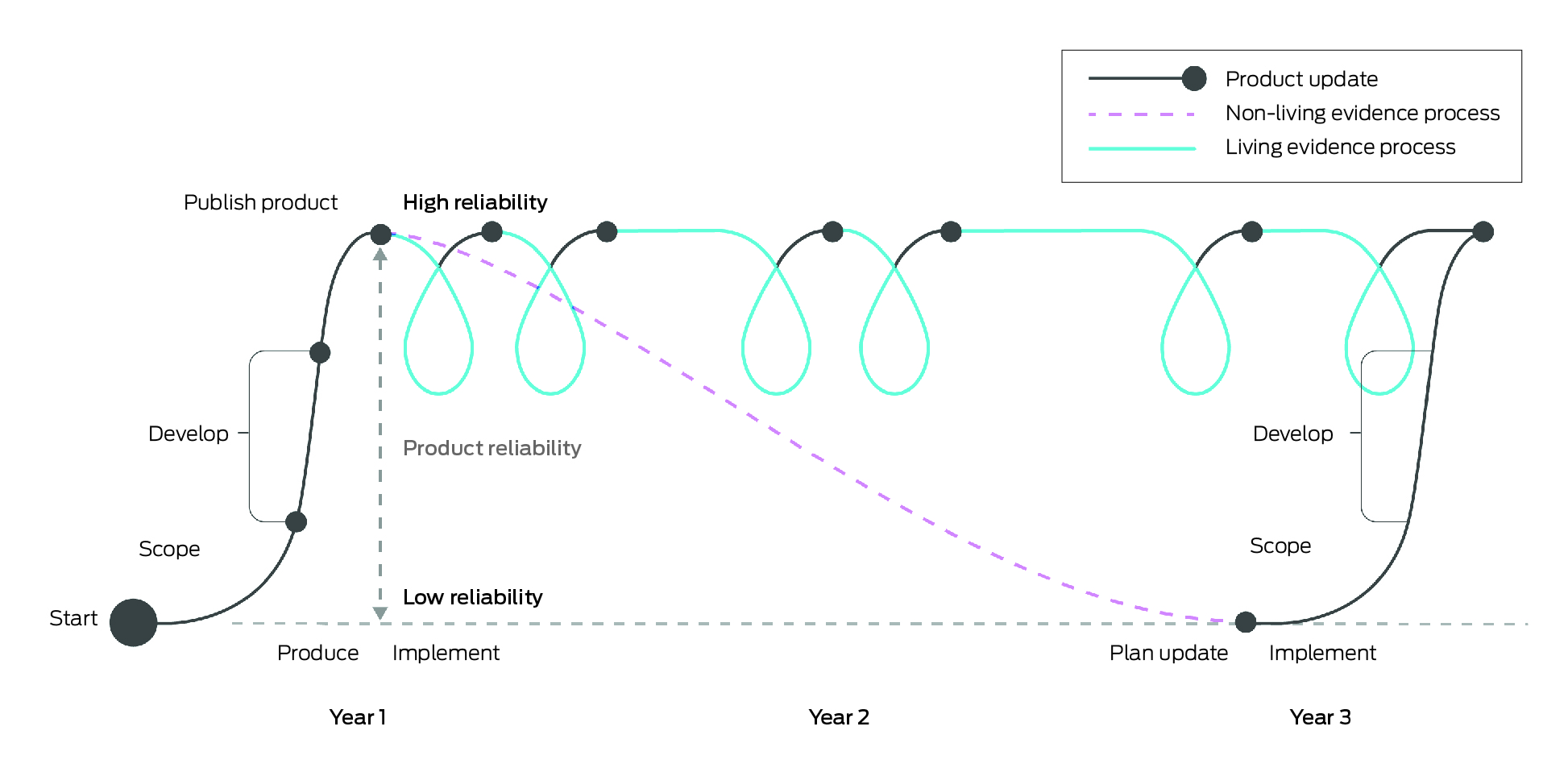

Living evidence syntheses are continually updated, systematically appraised summaries of research evidence. These may include living systematic reviews, living evidence briefs or living evidence‐based guidelines.1,2 Compared with non‐living approaches, which are onerous to produce and become rapidly out of date, living evidence syntheses provide health system decision makers with highly reliable and, where appropriate, contextualised summaries of evidence as evidence emerges in near real‐time. The Box illustrates the differences between a living and non‐living evidence review. This revolutionary method of rapid evidence gathering, appraisal and synthesis, known as living evidence, has become feasible with methodological and technological advances in the past five to ten years.

The prospect of rapid translation of research on health policy through living evidence has been embraced globally, with the World Health Organization, Cochrane, Pan American Health Organization, United States Government, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence all committing to adopting living evidence approaches. However, the use of living evidence to date has been focused primarily on discrete clinical areas, such as treatments for stroke and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19).3,4 We believe there is an opportunity to realise the substantial potential benefits of living evidence for health systems, and to lead this field internationally by co‐creating mechanisms and strengthening knowledge translation architecture to encourage living evidence use in health policy. A critical early step in realising this ambition is to establish an Australian research agenda to understand and advance living evidence for policy.

Living evidence approaches have the potential to improve the impact of evidence on health policies and population outcomes.5 They do so by addressing some of the known barriers to evidence‐informed policy, such as misaligned timing between evidence production and policy development; differences in context between researchers and policy makers; and lack of resources or capability to find reliable evidence within policy settings.6,7,8 Where there is ongoing, trusted collaboration in developing living evidence syntheses, this may further enable researchers and policy makers to navigate the complexities of translating evidence into policy together.

For example, the COVID‐19 pandemic presented a substantial challenge for Australian health decision makers to ensure that policy decisions kept pace with societal needs. Collaborative living evidence played a crucial role in this period. Rapidly emerging voluminous research meant that living evidence approaches were a key mechanism for providing decision makers with the best available evidence to inform health system responses.4,5 The National Clinical Evidence Taskforce's (NCET) living evidence approach involved working closely with over 35 clinical organisations and policy stakeholders to understand evolving evidence needs and ensure that evidence moved swiftly from publication of research studies, to appraisal, through to synthesis of recommendations for clinical care, thus enabling rapid implementation by practitioners and policy makers.4 An evaluation of the NCET found that this model was considered to be “very” or “extremely” valuable to clinicians and policy makers.9

The living evidence approaches currently applied for clinical topics in Australia (eg, English and colleagues3, White and colleagues10, Navarro and colleagues11) are considered international best practice. The Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges noted that: “If Australia can go for the gold with its national health guidelines, why can't we do it [in international health contexts] and for other sectors?”.12 The opportunity for Australia now is to strengthen this capability and leadership to systematically and rigorously understand and normalise the routine and effective use of living evidence across health system policy and practice.

Australia has implemented living evidence for several key clinical concerns; however, the routine implementation of living evidence in health policy is nascent and knowledge gaps remain on how to best do this. We believe realising this opportunity requires a national research agenda, because without one, we are likely to forego many potential benefits and positive health system impacts of living evidence.

Benefits of a national research agenda for translating living evidence into health policy in Australia

Strengthening policy decisions with up‐to‐date evidence

Policy that is informed by the current body of evidence is likely to produce better outcomes than policy that is informed by individual studies, older evidence or no evidence at all. Living evidence approaches enable access to up‐to‐date, carefully appraised and synthesised evidence for policy‐relevant topics (eg, New South Wales Government Agency for Clinical Innovation13). Thus, where living evidence is used to respond to policy needs, it may help policy makers make decisions that are informed by emerging and relevant research evidence, and where these policy questions are similar across jurisdictions, living evidence may reduce the duplication of evidence synthesis efforts across jurisdictions.

Strengthening evidence use across the Australian health system

The use of evidence to inform policy decisions varies across the Australian health system. For example, although at the federal level, Australia has established rigorous methods for using evidence in coverage decisions for some of our largest health system spends (eg, the Commonwealth Medicare Benefits Schedule, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and National Immunisation Program), many other health decisions do not routinely use evidence. Although policy makers do seek and use evidence in decision making, this is contingent on the capacity and motivation of individuals and the policy context to seek, appraise and integrate evidence into the decision‐making processes.8 Yet, even these rigorous approaches do not guarantee that the evidence that informs policy is up to date. By collaborating with policy makers to generate living evidence syntheses to address policy questions and ensuring that these are always up to date, living evidence potentially addresses a longstanding gap in evidence syntheses to enhance translation of real‐time evidence into policy.14

Strengthening a learning health system

There is a growing drive in Australia and internationally to establish learning health systems so that person and community centricity in health decisions may be enhanced. The concept and practice of learning health systems envisage health systems in which local data and experience are systematically integrated with research evidence, and that knowledge is translated continuously into policy and practice.15 Learning health systems are enabled by linking information from clinical registries and adaptive trials, and through advances in precision medicine, artificial intelligence and other technological solutions.16,17,18 Living evidence could be a powerful tool to harness these advances to identify and integrate bodies of evidence into health system decisions more efficiently and effectively.

Continue Australian leadership in this area

Already recognised as global leaders in living evidence development, Australia has the opportunity to expand this leadership. We can achieve this through collaborative empirical research that enhances the infrastructure for conducting living evidence and strengthens the capacity of the health system to understand and adopt living evidence approaches. These goals align with global evidence implementation priorities: (i) “Formalise and strengthen domestic evidence‐support systems”; and (ii) “Enhance and leverage the global evidence architecture”,12 and positions Australia at the forefront of this work internationally.

Establishing a national research agenda

A national research agenda for incorporating living evidence into the policy process should involve sector‐wide collaboration and meaningful consultation to develop priorities, leverage interdisciplinary expertise, establish transparent and standardised techniques and encourage collaboration. The national research agenda should be revisited periodically to reflect on learnings and spearhead new research to enable up‐to‐date, evidence‐informed person‐ and community‐centred care. Given our experience in the living evidence space, we see the following questions as major priorities for that agenda.

When is living evidence likely to be beneficial to policy?

There are no established criteria or guidelines for when to employ a living evidence approach. In clinical settings, living evidence is recommended for topics where: (i) the topic is a high priority for decision making; (ii) there is uncertainty in the existing evidence; and (iii) new evidence is emerging or expected to emerge soon.11 These criteria are likely to apply in health policy settings but there may be additional criteria to consider, such as an enabling environment for rapid policy uptake or where policy contexts are changing. It is important to define these criteria so that policy makers are informed when making decisions about supporting living evidence production and use.

What are the benefits and risks of living evidence for policy?

The best described benefit of living evidence for policy is the availability of up‐to‐date evidence to inform decision making.9,19 There might be additional benefits, such as enhancing credibility of policy makers and quality of policies that use up‐to‐date evidence, increasing evidence literacy through sustained collaboration with living evidence producers, and strengthening capacity to access up‐to‐date research through enduring mechanisms for partnership and interaction. Conversely, a potential risk for living evidence use in policy is that rapidly changing evidence and associated policy changes might cause confusion and scepticism, if not communicated appropriately.20 Similarly, suboptimal translation of living evidence into policy7 risks wasting the opportunities afforded by living evidence. By understanding the potential benefits and risks of living evidence for health policy, and working with producers of living evidence, policy makers and communities, we can be more considered in working to enhance the benefits and avoid the risks.

What model of living evidence is effective and scalable at delivering these benefits?

Although the core components of living evidence are established, the task ahead is to understand what other elements make up an effective model of living evidence for policy. For example, the NCET produced weekly updates of the COVID‐19 guidelines and actively sought to sustain meaningful collaboration with users of the evidence.9 Meaningful, sustained collaborations between researchers and policy makers are a core mechanism, known to improve translation of evidence into policy21 and might have enabled the high acceptance and impact of this emergency initiative. Other elements of the NCET COVID‐19 model (eg, weekly updates) are unlikely to be necessary or scalable for most policy issues.

What infrastructure is required to enable living evidence use in health policy? And how can the health system build this infrastructure?

Even when evidence answers a health policy question, it must be stewarded (often simultaneously) through multiple networks of organisations and settings within the health system that are each driven by their own priorities, capacity, culture and contexts.22,23 Research that explores how the health system could enable the uptake and application of living evidence products by policy makers — including retaining the fidelity of the emerging evidence in policy decisions; and whether these system changes are best driven through adaptive or transformational approaches — is crucial. Important areas for focus are understanding culture, processes, technology and infrastructure within health systems, including how these affect living evidence use in policy.

Additionally, recognising that evidence is one of many influences on policy,22,23 it is necessary to investigate how evidence generated through a living evidence model is perceived and modified by the other influences across diverse policy settings. Approaches using system modelling methods such as dynamic system modelling (where a collaborative approach is used to understand the nature of a problem, achieve consensus on the course of action and facilitate adoption of the change) could be used to maximise the perception and value of living evidence in policy making, therefore increasing the likelihood that it will be routinely used in health policy.24

How can research design advance the study of living evidence use in policy?

Theory‐driven research that seeks to understand how living evidence influences policy, how this approach can be optimised for policy making, and how the policy ecosystem can be enabled to use living evidence, will advance evidence‐informed policy research. This research would build on learnings from implementation science, political science, behavioural science and more, while drawing on collaborative expertise and structured empirical research.

Conclusion

In Australia, we have the opportunity to build on our leadership in living evidence to further our understanding of the living evidence model and create mechanisms that enable translation of living evidence into evidence‐informed policy. A national research agenda that is achieved through collaboration may strengthen not only the evidence‐into‐policy architecture in Australia but also enable Australia to lead this field internationally.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Cheyne S, Fraile Navarro D, Hill K, et al. Methods for living guidelines: early guidance based on practical experience. Paper 1: Introduction. J Clin Epidemiol 2023; 155: 84‐96.

- 2. Elliott JH, Synnot A, Turner T, et al. Living systematic review: 1. Introduction‐the why, what, when, and how. J Clin Epidemiol 2017; 91: 23‐30.

- 3. English C, Bayley M, Hill K, et al. Bringing stroke clinical guidelines to life. Int J Stroke 2019; 14: 337‐339.

- 4. Tendal B, Vogel JP, McDonald S, et al. Weekly updates of national living evidence‐based guidelines: methods for the Australian living guidelines for care of people with COVID‐19. J Clin Epidemiol 2021; 131: 11‐21.

- 5. Elliott J, Lawrence R, Minx JC, et al. Decision makers need constantly updated evidence synthesis. Nature 2021; 600: 383‐385.

- 6. Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, et al. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; 14: 2.

- 7. Masood S, Kothari A, Regan S. The use of research in public health policy: a systematic review. Evid Policy 2020; 16: 7‐43.

- 8. Dam JL, Nagorka‐Smith P, Waddell A, et al. Research evidence use in local government‐led public health interventions: a systematic review. Health Res Policy Syst 2023; 21: 67.

- 9. Millard T, Elliott JH, Green S, et al. Awareness, value and use of the Australian living guidelines for the clinical care of people with COVID‐19: an impact evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 2022; 143: 11‐21.

- 10. White H, Tendal B, Elliott J, et al. Breathing life into Australian diabetes clinical guidelines. Med J Aust 2020; 212: 250‐251. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2020/212/6/breathing‐life‐australian‐diabetes‐clinical‐guidelines

- 11. Navarro DF, Cheyne S, Turner T. The living guidelines handbook: guidance for the production and publication of living clinical practice guidelines. Version 1.0. Australian Living Evidence Consortium; 2022. https://livingevidence.org.au/resources (viewed Dec 2023).

- 12. Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges. Evidence commission update 2023: strengthening domestic evidence‐support systems, enhancing the global evidence architecture, and putting evidence at the centre of everyday life. Hamilton, Canada: McMaster Health Forum, 2023. chrome‐extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default‐source/evidence‐commission/update‐2023.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 13. NSW Government Agency for Clinical Innovation. Approaches to reduce surgical waiting time and waitlist [website]. https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/covid‐19/critical‐intelligence‐unit/surgery‐waitlist (viewed Oct 2023).

- 14. Verboom B, Baumann A. Mapping the qualitative evidence base on the use of research evidence in health policy‐making: a systematic review. Int J Health Policy Manag 2022; 11: 883‐898.

- 15. Enticott JC, Melder A, Johnson A, et al. A learning health system framework to operationalize health data to improve quality care: an Australian perspective. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8: 730021.

- 16. O'Shea R, Ma AS, Jamieson RV, Rankin NM. Precision medicine in Australia: now is the time to get it right. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 559‐563. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/7/precision‐medicine‐australia‐now‐time‐get‐it‐right

- 17. Holliday EG, Weaver N, Barker D, Oldmeadow C. Adapting clinical trials in health research: a guide for clinical researchers. Med J Aust 2023; 218: 451‐454. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/218/10/adapting‐clinical‐trials‐health‐research‐guide‐clinical‐researchers

- 18. Ahern S, Gabbe BJ, Green S, et al. Realising the potential: leveraging clinical quality registries for real world clinical research. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 273‐277. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/6/realising‐potential‐leveraging‐clinical‐quality‐registries‐real‐world‐clinical

- 19. English C, Hill K, Cadilhac DA, et al. Living clinical guidelines for stroke: updates, challenges and opportunities. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 510‐514. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/10/living‐clinical‐guidelines‐stroke‐updates‐challenges‐and‐opportunities

- 20. Ellis LA, Pomare C, Gillespie JA, et al. Changes in public perceptions and experiences of the Australian health‐care system: A decade of change. Health Expect 2021; 24: 95‐110.

- 21. Haynes A, Rowbotham SJ, Redman S, et al. What can we learn from interventions that aim to increase policy‐makers’ capacity to use research? A realist scoping review. Health Res Policy Syst 2018; 16: 31.

- 22. Bullock HL, Lavis JN, Wilson MG, et al. Understanding the implementation of evidence‐informed policies and practices from a policy perspective: a critical interpretive synthesis. Implement Sci 2021; 16: 18.

- 23. Redman S, Turner T, Davies H, et al. The SPIRIT action framework: a structured approach to selecting and testing strategies to increase the use of research in policy. Soc Sci Med 2015; 136‐137: 147‐155.

- 24. Atkinson JA, Wells R, Page A, et al. Applications of system dynamics modelling to support health policy. Public Health Res Pract 2015; 25: e2531531.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Monash University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Monash University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

No relevant disclosures.