The known: The Australian health care system requires innovative approaches to meet the rising demand for services. Virtual hospital (VH) models of care have shown promise in improving care efficiency and experiences while maintaining patient outcomes.

The new: Barriers to and facilitators of implementing and delivering VH services and gaps in evidence and practice were identified, setting a research and practice agenda for ongoing improvement.

The implications: Successful practices can be adopted by organisations looking to implement new VH services or improve existing VH services. Future research and policy changes should address gaps in evidence and practice; this should include the evaluation of care models and technologies, and development of funding models for VH services.

The Australian health care system faces rising demands for health services amid workforce shortages and growing health care needs.1,2 In hospitals, this strain is observed in the overcrowding of emergency departments, bed block, and increased pressure on hospital staff.3,4,5 Such issues can exacerbate wait times, compromise patient safety, and lead to poorer patient experiences and clinician burnout.6,7,8

Virtual hospitals (VHs), which use technology to provide hospital level care to patients in the community, have emerged as an innovative solution to improve care efficiency.9,10,11,12,13 VHs differ from telemedicine, with the former defined as services that provide continuous assistance to patients under formalised models of care (hereafter referred to as models), and the latter defined as one‐off virtual consultations between patients and clinicians.9

VH models have demonstrated promising outcomes, including low rates of adverse events, hospital admissions and readmissions,11,12,14,15,16,17,18 high levels of patient satisfaction,12,15,19 high levels of clinician satisfaction,10,12 and improved cost effectiveness,16 primarily in the management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). However, there is a lack of evidence on the factors that drive successful implementation and delivery of VH services, with existing research comprising perspective accounts of VH implementation20,21 and stakeholder experiences before implementation.9,22 To inform successful sustainment and scaling of VH services, evidence on the experiences and information needs of diverse stakeholders who are actively involved in the delivery of VH care is required.

In the current study, we aimed to address this knowledge gap by exploring the experiences of clinicians and senior managers involved in VH services at three sites. Our objective was to describe the barriers to and facilitators of implementing and delivering VH services, and the evidence and practice gaps where further research and policy changes are needed to drive continuous improvement, as perceived by individuals involved in delivering or managing VH care.

Methods

Setting

This study was part of a wider program of translational research on virtual care, led by Sydney Health Partners’ Virtual Care Clinical Academic Group, and represents a collaboration between academia and health services in New South Wales, Australia. To be eligible for participation, individuals were required to be involved in the delivery or management of VH services at one of the three Sydney Health Partners sites (Box 1).

Design

We used a qualitative descriptive study design to collect and analyse data due to its utility in comprehensively collecting and summarising attitudes towards events, and in informing policy and practice recommendations.23

Research team

Those of us who collected and analysed data included an experienced implementation scientist and senior academic (TS) and early career researchers (NN and KS) experienced in using qualitative methods in digital health research. Other authors of this article are academics, consumers, clinicians and/or health service leaders with diverse expertise across virtual care, digital health, health economics and human factors. Three of us (NN, KS and TS) engaged in collaborative reflexivity through ongoing discussion of emergent study findings with the other authors, which informed data collection and interpretation.24

Data collection

Participants were recruited with assistance from members of the Virtual Care Clinical Academic Group, which included representatives from all three study sites. Members provided us with contact information of potential participants (relevant staff in their organisation), and one of us (NN) approached potential participants via email. We used purposeful (intensity and heterogeneity) sampling of clinicians and managers with diverse experience and expertise (eg, professional background, qualifications, site) in VH care delivery to ensure that a wide range of perspectives were captured.25 One of us (NN) conducted semi‐structured interviews between July 2022 and April 2023 and another one of us (TS) conducted a focus group in February 2023. Interviews were conducted online via Zoom or, where possible, in person at participants’ workplaces. Interviews continued until inductive thematic saturation was reached (ie, no new codes emerged).26

A semi‐structured interview guide (Supporting Information, section 1) was developed by two of us (NN, TS) and discussed with theVirtual Care Clinical Academic Group leadership team, who had significant experience in delivering VH care. The guide was then tested before use with participants. Probing questions reflected the major domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research27 to ensure that experiences relating to the intervention, outer and inner settings, individuals involved, and the implementation process were explored. Interviews and focus groups were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Two of us (NN and KS) conducted inductive content analysis of de‐identified transcripts,28 using NVivo 14.23.0 (Lumivero), to develop codes relating to participants’ experiences with VH services. Six transcripts were independently analysed by NN and KS, who then met to compare analyses of these transcripts and develop an initial coding structure. The remaining transcripts were divided between NN and KS, who met periodically to discuss emergent codes and iterations to the coding structure. The final codes and coding structure were confirmed by all of us, and compared across different professional roles and VH sites.

Ethics approval, consent and reporting

Ethics approval for our study was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Protocol 2022/213) and written or verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. We report our study according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (Supporting Information, section 2).29

Results

Participants

A total of 22 individuals (11 male, 11 female) took part in the study (Box 2). One‐on‐one interviews (which lasted for an average of 41 minutes) were conducted with 20 participants and a focus group was held with five participants, including three who had been previously interviewed.

Primary themes

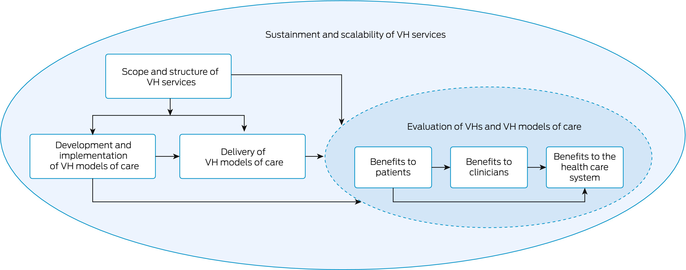

Five primary themes emerged: scope and structure of VHs; development and implementation of VH models; delivery of VH models; evaluation of VHs and VH models; and sustainment and scalability of VH services. Supporting quotes for these themes are shown in Box 3, and the themes are summarised schematically in Box 4.

Scope and structure of VH services

Each VH had been established at a different time and with different models, resources and reach (Box 1). Participants from all VHs raised the need to further define the role of the VH, including its goals and objectives and how services should be structured to achieve these. This included finding the niche in which VHs could provide the most benefit and supplement, but not duplicate, existing health services such as community general practices, primary health networks, urgent care centres, inpatient and outpatient departments, aged care services, and ambulance services. Partnerships with these external services were seen to be critical for enabling enhanced service integration and coordination between services, and for increasing awareness of and referrals to VH services.

Participants who were in leadership roles at VH B raised the importance of organisational structures that reflect those of traditional hospitals. Clinicians at all VHs indicated that the physical proximity of leadership in the VH enabled more effective and collaborative relationships than in traditional hospital settings.

Development and implementation of VH models

Identifying clinical needs and suitability of patients to VH models

Drivers for developing VH models included pain points identified in existing services; for example, common emergency department presentations that are amenable to a VH model, needs identified by clinical departments, and strategic imperatives from district executives or state government. When determining the suitability of clinical conditions and patients for a VH model, participants described looking to existing literature and collaborating extensively with relevant clinical departments. Participants described experiences where VH models could not be implemented, owing to the specialist department not being engaged or ready. One manager at VH B noted that having staff with fractional roles, where they split their time between the VH and the emergency department, could enhance collaboration.

Embedding technology in VH models

A barrier highlighted by participants from VH B was the perceived divide between clinical teams and information and communication technology (ICT) teams. These teams were described as having different languages, priorities and timelines that contributed to misalignment of approaches to embedding technology in VH models. Participants emphasised the importance of upskilling clinicians in design‐thinking approaches, to enable them to better contribute to technology development processes, and employing clinical informaticians who can “translate” between teams. Managers at VH C described a lack of information technology resources as a barrier to implementing VH models. ICT managers described challenges in the procurement of such resources, as there were few vendors with appropriate resources for supporting VH service needs. Another challenge that was described was government agencies procuring information technology resources for VHs across the state that did not fit with local organisational needs.

Implementing VH models

Managers perceived all VH models to be complex to implement. Models implemented to manage patients with COVID‐19 required the development of new clinical pathways and constant adaptation as new disease variants and guidelines emerged. Other models were perceived to be similarly, if not more, difficult to implement owing to their inherent disruptive nature and the change in clinical culture required — for example, shifting the responsibility of care from being led by medical specialists to being led by nursing or allied health staff. VH models therefore had to be implemented slowly, using a staged approach, while concurrently building specialists’ confidence in their safety and effectiveness. Participants who were in leadership roles stressed the importance of strong governance structures to ensure VH model safety and build clinicians’ confidence and buy‐in; they also acknowledged that further work is required to understand the effectiveness of different governance structures for VH care. The innovativeness of VH models meant an inevitable period of trial and error during implementation. Ongoing engagement with specialists was important to ensure that care was delivered as intended. While clinicians described experiencing change fatigue, they also felt that this innovativeness contributed to the appeal of working in VHs and they were generally not opposed to changes being made if they were proven to benefit care and were appropriately communicated. Nurses described being flexible and adaptable as core qualities needed in the VH setting.

Delivery of VH models

The methods and frequency of care delivery, technology used, and staff involved differed across different VH models and different levels of patient acuity within models.

Staffing

Clinicians in all VHs emphasised the importance of having access to a comprehensive multidisciplinary team in the VH setting, just as they would in an inpatient hospital, to facilitate efficient referrals and escalation of care. Collocation of staff was perceived to allow for collegiality to be built. The importance of administrative staff to support clinicians was also raised. Participants who were in leadership roles at VHs B and C acknowledged the need to further explore VH workforce design and staffing ratios, such as nurse‐to‐doctor ratios.

Hybrid care, care pathways and escalation

Participants from all VHs emphasised that hybrid or blended services provided the most added value and facilitated the appropriate escalation of care. Hybrid care enhanced existing services by delivering certain interactions in the patient journey virtually or by providing virtual options to patients, rather than replacing face‐to‐face care completely. However, it was acknowledged that work is still required to understand the optimal balance between face‐to‐face and virtual care. Clear and documented care pathways and escalation processes were also seen to be essential for the safe delivery of care. Escalation processes included those internal to the VH, such as nurses requesting that patients be reviewed by a doctor, or external, such as integration with primary care and ambulance services. Strong partnerships with these services were seen as critical for enabling effective escalation and onward referrals.

Workforce skills and capabilities

Participants from all VHs described the different skills and capabilities required to deliver care in virtual settings compared with those needed in face‐to‐face settings. Clinicians highlighted the importance of having technical competencies, using different questioning styles to assess patients, and having mental flexibility to rapidly switch between different patient cohorts. Participants from all VHs recognised the virtual care expertise of clinicians in their organisations and stressed that such expertise should be compensated appropriately. Participants also raised the need for further education and training to build a skilled virtual care workforce, including incorporation of virtual care content into university programs and rotation of staff through VHs.

Equity of access to care

Participants were concerned that minority populations could face greater barriers to accessing VH services. Such populations included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations, those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, older people, socio‐economically disadvantaged people, and those with other accessibility limitations, such as hearing impairments. Clinicians from all VHs felt that it was particularly difficult to connect with patients who had low English language proficiency, even when interpreters were available. Participants stressed that further research was required to understand the needs of patients from diverse groups and how they could be addressed to ensure that the VH did not create further inequity.

Use of technology in care delivery

Participants used a range of technologies that differed within and between VHs and VH models (Box 1). Clinicians from VH C used audio‐only teleconferencing, and consequently described having to rely more on patients’ own assessments of their health, which was highly subjective and variable between patients. Barriers to building rapport, owing to the lack of non‐verbal cues (eg, facial expressions), were also identified. With regard to videoconferencing, clinicians from VH A and VH B noted the lack of non‐verbal communication and physical touch, and the need for appropriate smart devices and internet connectivity at the patients’ end, as barriers. Clinicians described employing workarounds to combat system limitations, such as asking patients to send photos via SMS if video was pixelated or not available.

Only VH B and VH C used remote monitoring devices. While participants from VH A believed remote monitoring could expand the capacity of their services, no suitable technologies were available for paediatric populations. Participants from VH C described pulse oximeters as being particularly useful in the absence of videoconferencing. While participants from all VHs were interested in expanding the toolkit of remote monitoring devices, such as blood pressure monitors, Holter monitors, stethoscopes and blood testing devices, they acknowledged the need to further evaluate the impacts of different devices on care delivery. Participants who were in ICT leadership roles described logistical challenges in delivering patient‐facing devices, including providing remote monitoring and smart devices to patients who did not have their own.

A lack of interoperability and integration between systems was perceived to decrease care efficiency and coordination, and increase the potential for errors. This included the lack of automatic integration of readings from remote monitoring devices into the electronic medical record system, and a lack of interoperability between the VH's electronic medical record and other clinical information systems (such as those used in hospital departments, general practices and pathology services, and My Health Record [the national patient health record]). Participants from VH A and VH B further cited the use of paper‐based systems for prescribing as a challenge.

Clinical decision support systems were perceived to support the safe delivery of care. Clinicians from VH B used a clinical dashboard that enabled visualisation of patient details, risk status and remote monitoring device data across models, which they perceived to improve efficiency. Participants who were in leadership roles at VH B felt that the dashboard was an essential part of the infrastructure that enabled model scale‐up, while those from VH A reported that clinical decision support systems improved nurses’ confidence in performing clinical assessments that would have been completed by medical staff in traditional care models.

Evaluation of VHs and VH models

Participants described diverse benefits of VH models but also perceived gaps in evaluation. Although the specific outcomes targeted by care models were different within and between VHs, participants acknowledged that a more consistent approach to evaluation and key indicators of performance would be useful to enable benchmarking.

Benefits to the health care system

VHs were perceived to provide an alternative to traditional care that could reduce presentations to emergency departments, improve patient flow, and reduce admissions and re‐admissions to hospital. They were seen to be a sustainability strategy for the health care system, providing wider reach than traditional community care models, such as hospital‐in‐the‐home programs. However, the need for further evidence on the value and safety of VH models using objective indicators, such as actual reductions in emergency department presentations, was highlighted. Demonstrating these benefits was seen to be an important factor that could lead to an increase in clinicians’ overall acceptance of and confidence in VHs and attract ongoing funding.

While participants highlighted the potential for VHs to deliver cost savings to the health care system, it was emphasised that further economic analyses, including for different casemixes, levels of patient acuity and staffing structures, were required. In addition, participants described a need for further evidence that outlines why and how VHs work.

Benefits to patients

Benefits to patients were cited as the key drivers for VHs over traditional services. These included improving patients’ experiences by increasing convenience and comfort, providing enhanced reassurance, and improving empowerment and autonomy. Participants from VH A and VH B felt that 24/7 access to care provided enhanced opportunity for flexibility and patient‐centredness. Improvements to patient safety in VHs were frequently mentioned, including the ability to monitor patients more closely in the community and avoidance of unnecessary time spent in hospital. However, potential risks to patient safety, such as missing indicators of deterioration, were also raised.

Benefits to clinicians

Clinicians cited improved convenience, less physically demanding work and improved safety as benefits of working in VHs. VHs were seen to be particularly beneficial for nursing staff who have medical conditions or physical limitations that prevent them from working in traditional health care settings. In addition, some clinicians felt that VHs provide more opportunity to learn and receive feedback from colleagues than other health care settings.

Sustainment and scalability of VH services

Participants expressed interest in expanding VH models to new conditions, but they felt there was a lack of evidence to guide the development and implementation of new models and the ongoing improvement of existing models. Participants highlighted a need for additional resources, such as blueprints and templates that could facilitate the development of new care models. The need for a research agenda that outlines and prioritises evidence gaps for the ongoing improvement of VH services was also raised. In the absence of evidence, participants from all VHs highlighted the importance of networks to enable the sharing of information and lessons learnt between organisations.

Managers from all VHs described the need for national policies, funding and frameworks to support the sustainability and scaling of VHs. They noted that VH services did not meet the existing definition for activity‐based care in Australia and therefore VHs did not have designated funding models.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the barriers, facilitators, and gaps in evidence and practice that affect implementation, evaluation and improvement of VH services. To our knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively explore and compare the experiences of individuals involved in VH services across multiple sites with diverse structures and resources. Our findings shed light on the factors that influence the success of VHs and highlight barriers and gaps where further research or development is warranted.

While previous research has defined VHs as services that provide ongoing virtual care to patients in their homes,9 all VH sites in our study used face‐to‐face services in some capacity. We found that hybrid or blended models were perceived to support the safe delivery of care and enhance patient‐centredness. Other experiences that were shared across the leadership of VH sites included the importance of partnerships with health services that were external to, but connected with, VH services and the need for interoperable technology to support these relationships. Although these issues are not new,30 the positioning of VHs as a vehicle for integrated and coordinated care magnified these issues. Successful practices shared across VHs, such as hybrid care models, effective organisational leadership and communication, and staff competencies, provide insight on factors that facilitate VH effectiveness and should be harnessed when establishing new services.

Although some of the issues that we identified — including equity of access,31,32 technology challenges,33,34 skill requirements35 and funding models36 — have been highlighted previously in the virtual care literature, our study confirms and expands on their importance in VH‐specific settings. Such issues should be addressed through further research, technology development, and education and policy changes. In addition, we identified experiences that appear to be unique to VHs over telemedicine services, such as the importance of collocated multidisciplinary teams and extensive engagement with specialists and other stakeholders; these experiences should be considered when developing and implementing VH services.

Another key contribution of our study is the identification of perceived gaps in current research and practice which, if filled, could help to drive ongoing improvements to VH services. Interestingly, our findings addressed some gaps raised by participants in the study, which included insight into the factors that make VHs successful and the development of a research agenda to address gaps in evidence. Other prominent gaps which warrant further research included the need to evaluate the tangible impact of different VH models, refine the scope of VHs, and evaluate the different technologies used in VHs. A comprehensive list of evidence gaps identified in this study is presented and prioritised in an accompanying publication.37

An important limitation of this study is that some stakeholders involved in VH care delivery, such as consumers, community general practitioners and specialists, were not included. Although we explored perceived barriers, facilitators and gaps relating to consumer experiences of VHs from the perspectives of VH clinicians and leadership, these may differ from actual consumer experiences of VHs. Thus, the experiences of consumers and others involved in VH services should be explored in future studies.

In conclusion, the health care system must find new ways of responding to the rising demand for services and consumers’ expectations of increased convenience, flexibility and empowerment in their care.38 As digitally enabled care models continue to grow, it is imperative that they are appropriately structured to achieve their intended outcomes while maintaining patient safety. Our analysis revealed that, as well as myriad benefits, there are significant gaps in evidence and practice that must be addressed to enable successful scaling of safe and effective VH services.

Box 1 – Characteristics of the three included virtual hospitals at the time of the study (July 2022 to April 2023)

|

Site |

Types of patients |

Reach |

Date established |

Virtual and hybrid models of care |

Clinical staffing* |

Hours of operation |

Face‐to‐face services |

Technologies used* |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Virtual hospital A |

Paediatric patients |

Across New South Wales |

June 2021 (during the COVID‐19 pandemic) |

Nine care models across medical and surgical conditions, addressing diverse aims |

Medical and nursing staff, with access to allied health workers (physiotherapist, Aboriginal health worker, social worker) |

24 hours per day, 7 days per week |

External face‐to‐face services (eg, mobile doctor services) |

Audiovisual teleconferencing, SMS system, CDS system (for secondary triage risk assessment), and EMR |

|||||||

|

Virtual hospital B |

Adults (and paediatric patients who had COVID‐19) |

Metropolitan local health district |

February 2020 (before the COVID‐19 pandemic) |

Fifteen care models across different medical, surgical and social conditions, addressing diverse aims |

Medical staff (staff specialists, registrars, visiting medical officers), nursing staff (specialist nurse practitioners, clinical nurse consultants, clinical nurse specialists), and allied health workers (psychologists, social workers, physiotherapists, speech pathologists, occupational therapists, dietitians, Aboriginal health workers) |

24 hours per day, 7 days per week |

Integrated community nursing and allied health services |

Audiovisual teleconferencing, RMDs (pulse oximeters, thermometers, blood pressure monitors), mobile applications (integrating RMD signals across care models and care model‐specific applications), CDS system (clinical dashboard with patient details, risk status, RMD data), SMS system, and shared EMR at point of care |

|||||||

|

Virtual hospital C |

Adults |

Metropolitan local health district |

April 2020 (in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic) |

Two care models supporting patients with acute and urgent care needs (medical pathway and COVID‐19 model of care) |

Medical and nursing staff, and allied health worker (social worker) |

8 am–8 pm, 7 days per week |

External face‐to‐face services (eg, hospital‐in‐the‐home service, mobile doctor services) |

Audio‐only teleconferencing, RMDs (pulse oximeters), CDS system (for patient risk monitoring), and EMR |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CDS = clinical decision support; COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; EMR = electronic medical record; RMD = remote monitoring device. * Varied across models of care. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Roles and hospital affiliations of participants

|

Role |

Virtual hospital A |

Virtual hospital B |

Virtual hospital C |

Total |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Nurse |

0 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

|||||||||||

|

Physician |

2 |

1 |

1 |

4 |

|||||||||||

|

Allied health practitioner |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||||

|

Clinical or administrative manager/leadership |

2 |

5 |

3 |

10 |

|||||||||||

|

Information and communication technology manager/leadership |

0 |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|||||||||||

|

Total |

4 |

10 |

8 |

22 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Barriers, facilitators, and evidence and practice gaps raised by participants, grouped by themes and subthemes

|

Barrier, facilitator or gap |

Quote |

Participant |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Scope and structure of VH services |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Defining the role of the VH (gap) |

“… there are certain conditions, and certain needs which can't be met easily in the community … And I think the virtual hospital being a service that has both specialist care and GPs, we're really in a good position to fill that gap.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“… having a space where you've got a floor and you've got people, and you've got clearly identified roles and focus within it … that to me is the big difference [compared with other services].” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Partnerships with external services (gap) |

“I think part of it will be actually nutting out what we do and how we add on rather than take away from people's core business … how we can work together.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“One of the functions that we provide is the bridge between the hospital system and primary care and community health.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Organisational structures (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Proximity of leadership (facilitator) |

“There's many opportunities to work very closely with … directors, our director of nursing, and our general manager … there's a really open relationship to work collaboratively on a lot of the processes in [VH B].” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Temporary staffing contracts (barrier) |

“… we're still on temporary money. I've had a short term appointment increased every 3 months … there's a lack of certainty.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Development and implementation of VH models of care |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Identifying clinical needs and suitability of patients to virtual hospital care models |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Collaboration with specialist departments (facilitator) |

“… [the need] has to come [from] within the team themselves. Pushing virtual models of care onto teams that aren't ready for it just won't work. You need the engagement …They need to believe in it.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“And it's how you can come in and complement it and build that trust and relationship with them. And it's not a quick process. So there's a lot of stakeholder engagement.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Fractional roles (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Social complexity (barrier) |

“… [patients] have to be able to self‐manage or have someone to help them to do that.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Embedding technology in care models |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Misalignment between ICT and clinical teams (barrier) |

“We speak very different languages, we've got very different cultures, we have very different priorities. We're focused, of course, on the clinical care to the patient and they're focused on a whole lot of other things.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“I just assumed that people understood the technology … and vis‐à‐vis they had made assumptions about what I would know about the clinical model of care and the validity of the data that they needed.” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“It's difficult for us from a technology perspective because we're coming in halfway through a concept being developed and therefore processes have already been determined. Whereas, what ideally needs to happen is that we would be at the table from day one. Again, not there to drive the clinical aspects but there to drive the technology.” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Upskilling clinicians and managers (facilitator) |

“If we are going to do this meaningfully, then we need to build the expertise of our clinical community to use the technology, of our administrators to be able to make choices about which technology to invest in.” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Clinical informaticians (facilitator) |

“I see informatics as the translators. So you know, they're clinicians with an interest in digital health and they talk to our ICT colleagues and then, you know, translate that into a language that we can understand and that's relevant to us.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Procurement and assessment of technology (barrier) |

“In choosing technology, there are very limited suppliers that have consumer‐grade apps that work with our systems, and the ones that do, there's a lot of smoke and mirrors in what they're offering. The maturity of the product is just not where it needs to be … we've got a long way to go from the vendor community and the supply community.” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Lack of ICT resources (barrier) |

“… we don't have that kind of immediacy, so if we need something [in the EMR] changed we've got to fill out the form, go through the committee. They'll see if they've got time to do it.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Modifying the EMR to cater for VHs (barrier) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Care model implementation |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Disruption to clinical culture (barrier) |

“… a lot of what we're doing is very political and it's very disruptive to the system. And a lot of what we're doing is changing clinical culture. A lot of negotiation, a lot of reassurance with evidence to date and progress and patient experience and nil adverse outcomes … but it takes time.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Staged approach to implementation (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Governance structures (facilitator and gap) |

“What are the different governance structures that are in place? Which ones are effective, and which ones aren't? Because I think people need to know how to set up virtual health safely, and it's not about just a relationship between a clinician and a patient.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Ongoing engagement with specialists (facilitator) |

“The biggest thing is that we maintain communication [with specialists], so that we can constantly ensure that the care provided is what the cohort was designed to be, because things constantly change.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Change fatigue (barrier) and mitigating change fatigue (facilitator) |

“I think the big challenge as a nurse is just picking things up quickly and just accepting them as changed. And as long as it's evidence‐based changes, I think most people are okay with that. Not just change for the sake of change.” |

Clinician, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“… this term is used a lot here about change fatigue … everybody is very aware here, of changes and just how it can get really hard to keep up with the changes here.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“It's kind of been amazing to have input and then see that come to fruition in a way as well. In a hospital, it would take 5 years to get a sign changed … nothing really ever changed in the hospital. You didn't see a real lot of change, whereas in virtual things change so, so quickly.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Flexible and adaptable attitude (facilitator) |

“It's kind of just one of the known things of virtual, it's just things change from week to week. You'll have 2 days off and things will completely, completely change. Our nurses are so amazing with change here … they're so adaptable.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Delivery of VH models of care |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Staffing |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Multidisciplinary team (facilitator) |

“At [VH C], they're literally under one roof. And then the virtual space, I'd like them to be virtually under the one roof. So they will be part of my team, and it will be a smooth line.” |

Clinician, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Collocation of staff (facilitator) |

“So, I didn't actually see them, but I was speaking to them every day … when you work in a multidisciplinary team, one of the joys is being able to interact with your colleagues. So, longer term, [not being collocated] could have been a problem.” |

Clinician, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Administrative staff (facilitator) |

“You can't just have one doctor, you need to have an administrative officer and all that attached to it, to help with the paperwork or the emailing and all of that. Having all that wraparound support is gonna be crucial in order for virtual care to continue.” |

Clinician, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

Hybrid care, care pathways and escalation |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Understanding the right balance of face‐to‐face versus virtual (gap) |

“… to work out what still needs to occur face to face and what is better face to face, and what is reasonable and acceptable to occur virtually and what's actually better virtually.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Clear escalation processes (facilitator) |

“… if a patient is on a model of care and the journey of care is not going well and the patient's deteriorating, we're putting them off the model to a higher level of care.” |

Clinical manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“Our referral pathways become very important because we don't have immediate access to other types of support, so if you've got someone in a hospital bed you press a button on the wall and the team comes and you've got everything in place. But where you've got someone on the other end of the phone, you're relying on the ambulance, or your guidance to get them through that. I think that's really important for patient safety and where we sit within that space.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Clear clinical governance (facilitator) |

“… that's really unique about virtual care versus telehealth, in that to do it well, you have to have the clinical governance model right.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Partnerships with external services (facilitator) |

“… that's the thing that's really important to understand is, that it's not a standalone model … it is an integrated model. We have a virtual hospital that is absolutely integrated with the rest of the system, and working really closely with them.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“One of the things that we try and do is make sure there's proper handover to the GP, there's appropriate communication with the GP, encourage interactions and discussions with the GP while we're looking after patients under our care.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Workforce skills and capabilities |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Technical competencies (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Building rapport (facilitator) |

“… it does require a nurse to build that trust and rapport very quickly in that early conversation to ensure that the patient is happy and willing to do a videoconference.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Different skills for virtual assessment (facilitator) |

“Clinicians need to be more in tune with looking for other indicators, or other triggers, or things that may give them an idea that something else is going on … you really need to have a listen out for those non‐obvious signs that people may give you.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“… it's being aware that you should tell the patient, ‘Look, you know, I'm by myself. There's a background here, but, you know, just to let you know that it's all private.’ So, all those sort of soft, soft skills, I think are really important to integrate into our care.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Clinician expertise in virtual care (facilitator) |

“The skilled resources … that are doing the consultations are actually really quite senior clinicians that also have developed skills in running virtual consultations, which is … a skillset all of its own. So these are highly skilled clinical staff that need to be remunerated for the work that they do.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Mental flexibility (facilitator) |

“… a lot of us are in the real COVID mind, but then we get the palliative care calls, and that's a very different call … it's switching between brains.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Virtual care education and training (gap) |

“… some people are very good at it, some people are not very good at it. We're now sort of in big conversations about developing specific education, specific training, specific modules, and also, rotating staff through the virtual hospitals so that when they go off to become endocrinologists or cardiologists or whatever it is, they've had some experience in virtual health that they can take into their career.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Equity of access to care |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Specific patient populations face greater barriers (barrier and gap) |

“… the only one that I can say for sure are patients that speak English as a second language … that is a significant barrier if an interpreter is required to being able to conduct a virtual consultation … we do have interpreters join, but to my knowledge, they only join on the phone. So it's sort of they're on the loud speaker and it's a bit hard.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“… thinking about finances, not having Zoom on their phone or not having a smartphone, being elderly, hard of hearing, culturally and linguistically diverse, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. They all have these barriers, which also extend into virtual care.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Resources such as Aboriginal cultural support teams, digital patient navigators, outreach teams (facilitator) |

“… putting in place roles. Like we have a digital patient navigator and all these sorts of things, specific targeted strategies to make sure that language, culture, intellectual capability don't preclude your access to virtual care.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Difficulty in connecting with interpreter services (barrier) |

“… another barrier that we come across a lot with, is non‐English speaking patients, even using an interpreter to try get them to follow the instructions to come up to Zoom has been quite a challenge for us.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Use of technology in care delivery |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Detecting clinical signals (barrier) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Limited rapport and connection (barrier) |

“A lot of what we do as general practitioners is build rapport, build trust, and build reassurance, and I think part of the reason they come to us is to build that connection. And I feel, I don't know, I wonder if there's some of that is lost over Zoom and over voice.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Patient objections to video (barrier) |

“… but a lot of patients prefer, why not just do a phone call? Why go through all that trouble when we can just do a phone call. And patients aren't understanding the importance of actually visual assessments and visual inspections, which is why we reiterate to patients the importance of it.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Consumer devices and connectivity (barrier) |

“… that's limited by technology ‘cause not everyone has a phone that can do internet access, that can do telehealth.” |

Clinician, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Use of photos (facilitator) |

“… we've found ways to, to circumvent that, like getting them to email us or as MMSs, which gives us a clearer image.” |

Clinician, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

Extending and evaluating toolkit of remote monitoring devices (gap) |

“… the evidence that the remote monitoring's gonna make a difference. I think that's still a bit up in the air.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Lack of technology for paediatric populations (barrier) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Logistical challenges (barrier) |

“While it might be easy for me to go and buy a phone, it's not easy for me to get that phone in your hand as a consumer and have it be secure, ready, charged, you know how to use it. And then if it's a loaned device, how do I get it back and clean it and recharge it and send it out to the next patient?” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Integration between EMR and remote monitoring devices (barrier) |

“… the other challenge is integrating the wearables into our dashboards and our decision management systems, and our EMR. There's a lot of products out there. However, not all of it works … They don't play nicely together a lot of the time, which makes it really hard to integrate new products and to just get a single source of truth when you're reviewing a patient.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Interoperability between VH EMR and external service systems (barrier) |

“… things like electronic communication to the GP, discharge referring back to the GP … one of the biggest problems we face is that a lot of our facilities, departments and systems work on different platforms. They use different medical records. They use different patient flow mechanisms.” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Lack of e‐prescribing (barrier) |

“My biggest frustration is that we still have paper‐based medication prescribing process in the virtual hospital. That's just so far behind where we need to be.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Clinical decision support (facilitator) |

“[We use] an application which assists with clinical decision making as well as gives further information on likely diagnosis and information that can be shared with the parents … I think it really helps our nurses because they would otherwise feel it was out of scope for them to perform a clinical assessment on a patient and come to an outcome decision as this would usually be done by medical staff.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“… [the dashboard] is basic infrastructure for any kind of virtual hospital … that will just really allow ease of monitoring for the clinicians of a lot of patients at once and … simplify the process.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Need for enhanced usability of technologies for patients and clinicians (barrier and gap) |

“… you've got a whole bunch of problems here, you've got human factors issues [participant is describing human factors issues (ie, human/system interactions)] for the consumer, ‘cause now they've got to pair a device … with their phone and you might need to consider battery life, feasibility, do they have any disabilities or accessibility requirements? How are they gonna get the app on their phone? Is that app secure? Is it in language?” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Evaluation of VHs and VH models of care |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Evaluation frameworks and key performance indicators (gap) |

“… it depends on the context of what type of virtual care you're providing … there are process outcomes where you look at, the time, the consultation time it takes. And how many patients a provider can see in a day. But then you have all the other health outcomes there. Did this lead to the patient, receiving adequate care in a timely manner? Did the patient, I don't know, recover quicker, receive the correct diagnosis sooner?” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“I think there's a general question, because there's specific questions that go with the very different and quite complex sort of clinical areas. They're all going to be a little bit different … Encouraging services with similar patient cohorts to be looking at benchmarking with each other, I think's really important.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Benefits to the health care system |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Reducing emergency department presentations (facilitator) |

“… alleviate the burden on the current system, which is very heavy on doing face‐to‐face consultations … [patients] don't need to be escalated all the way to come to emergency or come in, wait a few days to see a paediatrician just for a simple question. So often people's concerns quickly escalate if they don't get any answers.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

Improving patient flow (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Reducing hospital admissions and readmissions (facilitator) |

“… there's been a lot of … hospital avoidance … with COVID patients [and] the palliative care patients as well. So being able to manage them as safely as we can at home, you know, without needing, them needing to go into hospital.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Early hospital discharge (facilitator) |

“… the other big one is to take people home earlier from hospitals. So some people with certain conditions stay in a hospital for, you know, a long period of time. It's costly and it occupies a bed that someone else with more acute needs might require, as well as all the burdens on the hospital staff who are quite highly specialised expert staff that don't necessarily need to be there to provide what that patient's receiving.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Supply versus demand (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Allow for wider reach (facilitator) |

“… we're able to manage a large volume of patients, and I mean very large volume of patients in that space, and confidently say that we're providing them with the information that they need.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Cost savings (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Economic analyses (gap) |

“I think there needs to be stronger economic analysis … can I take that patient, that clinical load, and reduce it by 80%, or can I change the casemix so that you see a different acuity and so that we get a better return on investment for those virtual care models? Or can I change things like the nursing ratio?” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Evidence on value and safety of care models (gap) |

“… to make sure that we've got the evidence that supports those sorts of efficiency projections in new hospital models of care. That will convince the federal government about where we need to draw the line between secondary health services and primary care. And how do we adjust funding to reflect that?” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Evidence outlining why and how VHs work (gap) |

“[We've had] all these people coming to us and saying, ‘Why does it work? Tell us how to do it.’ And we told them what our experience has been, but we don't actually know why it works and if it's replicable in other settings.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“… what enables us to do the things that we do, and do it reasonably quickly, and with quality? It's studying those structures and processes.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Benefits to patients |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Improved convenience (facilitator) |

“We offer types of services that just weren't available in the past … in the past, with treatment of tuberculosis, patient had to come in every day to basically be seen that they take their medication, because if they don't, if they miss a day, then they can get resistance. So now we can do that over virtual care and people used to have to organise their day around their TB meds, but now can do it from the comfort of their home and at any time of the day. So it's definitely a game changer in those sorts of areas.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Reassurance (facilitator) |

“I know from experience for a lot of carers, they just want a quick answer or they just need some quick reassurance and that's what virtual care can provide.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

Empowerment and autonomy (facilitator) |

“… empowerment of the patient as well. So [in traditional settings] they come into the clinic, and we do their blood pressure, we do their pulse oximeter readings, and we may not explain what they mean to the patient. We just sort of satisfy ourselves. But, you know, when we give them a pulse oximeter, we have to explain what's normal, what exactly are we measuring. And so patients are more involved in their care.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Coordination of care (facilitator) |

“Traditionally, we would just look at patients when they're in hospital, but obviously most patients go home and they still have health needs, even when they leave the hospital. So, I guess it's coordinating all those health needs.” |

Clinician, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

Some patients have preferences for face‐to‐face care (barrier) |

“… a lot of patients might still want, still prefer the face‐to‐face aspect of traditional nursing.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Patient safety (facilitator and barrier) |

“… the biggest thing is to me, I feel that there's less unnecessary risk for the patient from being in hospital unnecessarily. So things like falls, infection, medication errors.” |

Clinician, VH C |

|||||||||||||

|

|

“I think a flip side is that, potentially that one in, I'll say one in a million could have something that's missed, that would've been picked up face to face. Whereas I don't think there would be something that's missed face to face, but that would be picked up virtually.” |

Clinician, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

Benefits to clinicians |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Improved convenience (facilitator) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Less physically demanding work (facilitator) |

“… traditionally, without the care centre, if you're on the ward, if you're on light duties and you don't have a position available, it's like, you just, you can't work … so virtual have taken in a lot of nurses that are on light duties or have had injuries at work, but are able to work in an office setting while still continuing their nursing responsibilities and still continue to work.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Learning opportunities (facilitator) |

“In GP land, you might work in a small practice or you might work by yourself. So you don't get that collaborative approach. And you don't get often feedback on your work … and I get to see psychologists’ notes and physio notes. I get all that sort of MDT input as well.” |

Clinician, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Sustainment and scalability of VH services |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Evidence to guide development and implementation of new care models (gap) |

“It's around that translation into more settings in the community. So you've got the platforms in place to then have the flowers and flowers bloom. Lots of models of care that can reuse the same pieces of technology or the same approaches.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Research agenda (gap) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Information sharing (facilitator and gap) |

“I think that so often we get inundated with what we're doing ourselves that we don't look outside the box to see what other teams have done and kind of think, ‘Well, if they've done it like that, maybe I could do something within my own team that would support patients better.’ So, I think it's actually showcasing what other teams have done. Because then, teams will be able to look at that with a different lens to their own specialty to go, ‘Well, how could we do this? How could we do it differently?’” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH A |

|||||||||||||

|

National policies and frameworks (gap) |

“… there's no real legal or regulatory structure in place to make this work. There are going to be multiple issues that will continue to come up around access to the right type of devices, the security and privacy of information, the types of clinical services that should be made virtual care versus shouldn't, and there's no framework for any of that yet.” |

ICT manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

Funding models (gap) |

“… a hospital is defined in a very particular way and we don't officially fit into that, but we need to. The pricing for hospital‐level care, that's delivered here at the same level of quality, needs to be priced the same way.” |

Clinical/ administrative manager, VH B |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID = coronavirus disease; EMR = electronic medical record; GP = general practitioner; ICT = information and communication technology; MDT = multidisciplinary team; TB = tuberculosis; VH = virtual hospital. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 6 June 2024, accepted 20 August 2024

- Nicki Newton1

- Kavisha Shah1

- Miranda Shaw2

- Emma Charlston1

- Melissa T Baysari1

- Angus Ritchie3

- Chenyao Yu4

- Adam Johnston4

- Jagdev Singh5

- Meredith Makeham1

- Sarah Norris1

- Liliana Laranjo1,6

- Clara K Chow1,7

- Tim Shaw1

- 1 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 2 RPA Virtual Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW

- 4 Northern Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, NSW

- 5 virtualKIDS Urgent Care Service, Sydney, NSW

- 6 WentWest, Sydney, NSW

- 7 Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW

Data Sharing:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

This research was supported by Sydney Health Partners through the Clinical Academic Group funding scheme. We thank the Virtual Care Clinical Academic Group leadership team for their input into the conception of this study.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. McPake B, Mahal A. Addressing the needs of an aging population in the health system: the Australian case. Health Syst Reform 2017; 3: 236‐247.

- 2. Peters M. Time to solve persistent, pernicious and widespread nursing workforce shortages. Int Nurs Rev 2023; 70: 247‐253.

- 3. Richardson DB, Mountain D. Myths versus facts in emergency department overcrowding and hospital access block. Med J Aust 2009; 190: 369‐374. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2009/190/7/myths‐versus‐facts‐emergency‐department‐overcrowding‐and‐hospital‐access‐block

- 4. Xu HG, Johnston ANB, Greenslade JH, et al. Stressors and coping strategies of emergency department nurses and doctors: a cross‐sectional study. Australas Emerg Care 2019; 22: 180‐186.

- 5. Lim JC, Borland ML, Middleton PM, et al. Where are children seen in Australian emergency departments? Implications for research efforts. Emerg Med Australas 2021; 33: 631‐639.

- 6. Sartini M, Carbone A, Demartini A, et al. Overcrowding in emergency department: causes, consequences, and solutions—a narrative review. Healthcare (Basel) 2022; 10: 1625.

- 7. Bentz JA, Brundisini F, MacDougall D. Perspectives and experiences regarding the impacts of emergency department overcrowding: a rapid qualitative review: CADTH health technology review (Report No. HC0067). Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2023.

- 8. Elder E, Johnston ANB, Wallis M, Crilly J. The demoralisation of nurses and medical doctors working in the emergency department: a qualitative descriptive study. Int Emerg Nurs 2020; 52: 100841.

- 9. Bidoli C, Pegoraro V, Dal Mas F, et al. Virtual hospitals: the future of the healthcare system? An expert consensus. J Telemed Telecare 2023: 1357633X231173006.

- 10. Maniaci MJ, Maita K, Torres‐Guzman RA, et al. Provider evaluation of a novel virtual hybrid hospital at home model. Int J Gen Med 2022; 15: 1909‐1918.

- 11. Hutchings OR, Dearing C, Jagers D, et al. Virtual health care for community management of patients with COVID‐19 in Australia: observational cohort study. J Med Internet Res 2021; 23: e21064.

- 12. Lawrence J, Truong D, Dao A, Bryant PA. Virtual hospital‐level care‐feasibility, acceptability, safety and impact of a pilot hospital‐in‐the‐home model for COVID‐19 infection. Front Digit Health 2023; 5: 1068444.

- 13. Hole C, Munn LT, Swick M. The virtual hospital: an innovative solution for disaster response. J Nurs Adm 2021; 51: 500‐506.

- 14. Kastengren M, Frisk L, Winterfeldt L, et al. Implementation of Sweden's first digi‐physical hospital‐at‐home care model for high‐acuity patients. J Telemed Telecare 2024: 1357633X241232176.

- 15. Leenen JPL, Ardesch V, Patijn G. Remote home monitoring of continuous vital sign measurements by wearables in patients discharged after colorectal surgery: observational feasibility study. JMIR Perioper Med 2023; 6: e45113.

- 16. Levine DM, Ouchi K, Blanchfield B, et al. Hospital‐level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172: 77‐85.

- 17. Paulson MR, Shulman EP, Dunn AN, et al. Implementation of a virtual and in‐person hybrid hospital‐at‐home model in two geographically separate regions utilizing a single command center: a descriptive cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res 2023; 23: 139.

- 18. Sitammagari K, Murphy S, Kowalkowski M, et al. Insights from rapid deployment of a “virtual hospital” as standard care during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174: 192‐199.

- 19. Annis T, Pleasants S, Hultman G, et al. Rapid implementation of a COVID‐19 remote patient monitoring program. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27: 1326‐1330.

- 20. Shaw M, Anderson T, Sinclair T, et al. rpavirtual: Key lessons in healthcare organisational resilience in the time of COVID‐19. Int J Health Plann Manage 2022; 37: 1229‐1237.

- 21. Rothman RD, Delaney CP, Heaton BM, Hohman JA. Early experience and lessons following the implementation of a hospital‐at‐home program. J Hosp Med 2024; 19: 744‐748.

- 22. Melman A, Vella SP, Dodd RH, et al. Clinicians’ perspective on implementing virtual hospital care for low back pain: qualitative study. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol 2023; 10: e47227.

- 23. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000; 23: 334‐340.

- 24. Olmos‐Vega FM, Stalmeijer RE, Varpio L, Kahlke R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE Guide No. 149. Med Teach 2022; 45: 241‐251.

- 25. Suri H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual Res J 2011; 11: 63‐75.

- 26. Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018; 52: 1893‐1907.

- 27. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009; 4: 50.

- 28. Vears DF, Gillam L. Inductive content analysis: a guide for beginning qualitative researchers. Focus Health Prof Educ 2022; 23: 111‐127.

- 29. O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014; 89: 1245‐1251.

- 30. Samal L, Dykes PC, Greenberg JO, et al. Care coordination gaps due to lack of interoperability in the United States: a qualitative study and literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 143.

- 31. Gallegos‐Rejas VM, Kelly JT, Lucas K, et al. A cross‐sectional study exploring equity of access to telehealth in culturally and linguistically diverse communities in a major health service. Aust Health Rev 2023; 47: 721‐728.

- 32. Hall Dykgraaf S, Desborough J, Sturgiss E, et al. Older people, the digital divide and use of telehealth during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Aust J Gen Pract 2022; 51: 721‐724.

- 33. Hall Dykgraaf S, Desborough J, de Toca L, et al. “A decade's worth of work in a matter of days”: the journey to telehealth for the whole population in Australia. Int J Med Inform 2021; 151: 104483.

- 34. Rush KL, Howlett L, Munro A, Burton L. Videoconference compared with telephone in healthcare delivery: a systematic review. Int J Med Inform 2018; 118: 44‐53.

- 35. Curran V, Hollett A, Peddle E. Training for virtual care: what do the experts think? Digit Health 2023; 9: 20552076231179028.

- 36. Shaw J, Jamieson T, Agarwal P, et al. Virtual care policy recommendations for patient‐centred primary care: findings of a consensus policy dialogue using a nominal group technique. J Telemed Telecare 2018; 24: 608‐615.

- 37. Shah, K, Newton N, Charlston E, et al. Defining a core set of research and development priorities for virtual care in the post‐pandemic environment: a call to action. Med J Aust 2024; 221 (Suppl): S49‐S56.

- 38. Leimeister JM, Österle H, Alter S. Digital services for consumers. Electron Markets 2014; 24: 255‐258.

Abstract

Objective: To describe the barriers to and facilitators of implementing and delivering virtual hospital (VH) services, and evidence and practice gaps where further research and policy changes are needed to drive continuous improvement.

Study design: Qualitative descriptive study.

Setting, participants: Online semi‐structured interviews and a focus group were conducted between July 2022 and April 2023 with doctors, nurses and leadership staff involved in VH services at three sites in New South Wales, Australia.

Main outcome measures: Barriers to and facilitators of implementing and delivering VH services in sites with differing operating structures and levels of maturity, and evidence and practice gaps relating to VH services.

Results: A total of 22 individuals took part in the study. Barriers, facilitators, and evidence and practice gaps emerged within five major themes: scope and structure of VH services; development and implementation of VH models of care; delivery of VH models of care; evaluation of VHs and VH models of care; and sustainment and scalability of VH services. Facilitators of VH success included hybrid approaches to care, partnerships with external services, and skills of the VH workforce. Barriers and gaps in evidence and practice included technical challenges, the need to define the role of VH services, the need to evaluate the tangible impact of VH care models and technologies, and the need to develop funding models that support VH care delivery. Participants also highlighted the perceived impacts and benefits of VH services on the workforce (within and beyond the VH setting), consumers, and the health care system.

Conclusions: Our findings can help inform the development of new VH services and the improvement of existing VH services. As VH services become more mainstream, gaps in evidence and practice must be addressed by future research and policy changes to maximise the benefits.