Each year, one in seven Australian children and adolescents experience a mental disorder, but only half receive treatment.1 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reported that 6% of children aged 5–11 years and 13% of those aged 12–17 years used Medicare‐subsidised mental health services during 2021–22.2

We investigated the annual and cumulative incidence of Medicare‐subsidised mental health services for children during their first 15 years of life, and the demographic characteristics associated with the types of services used. We analysed Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) data for 86 759 children born during 1 January 2002 – 31 December 2005 and included in the New South Wales Child Development Study,3 or 94.7% of the record linkage cohort; 4848 children were excluded because information for socio‐demographic indices were not recorded in the 2009 NSW Australian Early Development Census.4 Record linkage was performed by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL) and the AIHW Data Integration Services Centre.

MBS records for mental health services (1 January 2002 – 31 December 2018) were categorised as being delivered by general practitioners (Better Access treatment plans), psychologists, psychiatrists, occupational therapists or social workers, or other (group therapy, psychological services provided by general practitioners or paediatricians) (Supporting Information, table 1). We assessed associations between demographic factors — sex, Indigenous status, socio‐economic position (Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage),5 geographic remoteness (Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia)6 — and each MBS‐subsidised mental health service type in univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses; we report odds ratios with 99.924% confidence intervals (Bonferroni‐adjusted for multiple testing). The NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee and ACT Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/18/ciphs/49) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Ethics Committee (EO2020/4/1026) approved the study. We report the study in accordance with the STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies.7

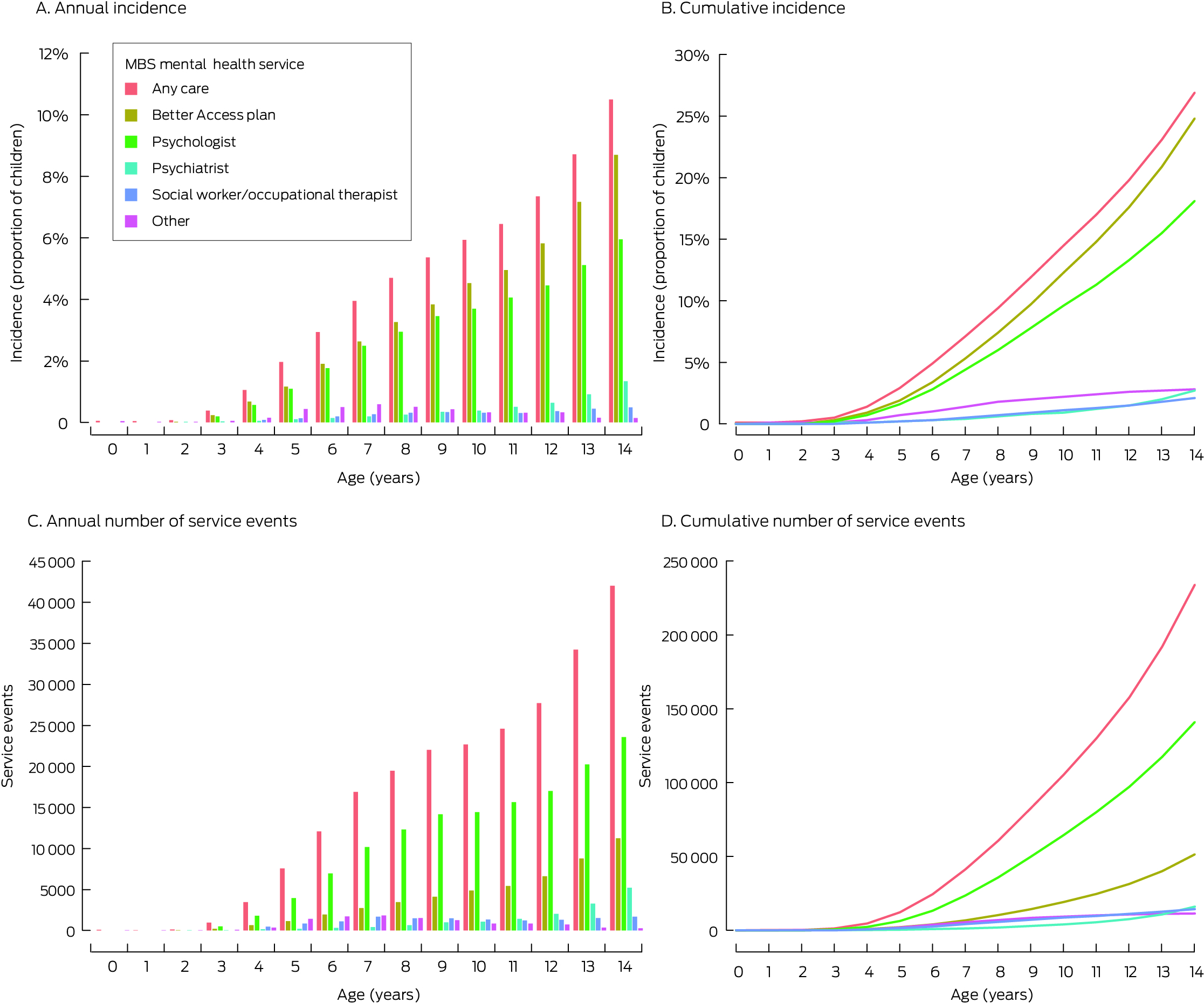

A total of 23 330 of 86 759 children (26.9%) had used MBS‐subsidised mental health services prior to their 15th birthdays: 21 535 had received Better Access plans (24.8%), 15 693 had received care from psychologists (18.1%), 2306 had consulted psychiatrists (2.7%), 1844 had received psychological therapy from occupational therapists or social workers (2.1%), and 2391 had received other mental health service types (2.8%) (Box 1). The annual and cumulative incidence of mental health service use each increased exponentially with age for Better Access plans and psychologist care, and more gradually for care from other mental health service providers (Box 2). Boys were more likely than girls to receive mental health services from occupational therapists or social workers or from other sources, and less likely to receive Better Access plans. Indigenous children and children living in postcodes of lower socio‐economic disadvantage were more likely to use any mental health service, including Better Access plans, psychologist care, and psychiatrist care. Children in inner regional areas were more likely than those in major cities to receive any mental health treatment, including Better Access plans, psychologist care, and services from occupational therapists or social workers; children in outer regional, remote, or very remote areas were less likely than children in major cities to use mental health services (any, Better Access plans, psychologist care). The likelihood of mental health service use by data follow‐up (31 December 2018) increased with age (Box 3).

We found that 26.9% of children had used Medicare‐subsidised mental health services before their 15th birthdays, a proportion considerably larger than the annual incidence at age 14 years (10.5%) or that reported in an earlier AIHW publication.2 The likelihood of mental health service use was lower among non‐Indigenous than Indigenous children and among children in socio‐economically disadvantaged or outer regional or remote areas, consistent with other reports.8,9 Girls were more likely than boys to receive Better Access plans, but boys were more likely to receive care from occupational therapists or social workers and use “other” mental health service types, possibly because of earlier detection of externalising disorders, which are more prevalent among boys.10 Service use was greater for children older at the time of follow‐up, probably because of the higher incidence of mental disorders during adolescence than earlier in life.2,10 The primary limitations of our study were the unavailability of data for mental health care not covered by MBS data (eg, Headspace, privately funded, hospital and emergency, and school‐based care) and the fact that we could not adjust our analyses for repeat presentations by individual children. Additional work is needed to ensure equitable access to mental health services for all young people in Australia.

Box 1 – Socio‐demographic characteristics of 86 759 New South Wales children who received Medicare Benefits Schedule‐subsidised mental health care before their 15th birthday, 2002–18, by service type

|

Characteristic |

All included children |

Any mental health service |

Better Access plan |

Psychologist |

Psychiatrist |

Occupational therapist or social worker |

Other services |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

All children |

86 759 |

23 330 |

21 535 |

15 693 |

2306 |

1844 |

2391 |

||||||||

|

Sex (boys) |

44 860 (51.7%) |

12 160 (52.1%) |

10 878 (50.5%) |

8292 (52.8%) |

1269 (55%) |

1036 (56.2%) |

1786 (74.7%) |

||||||||

|

Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander people |

6818 (7.9%) |

2385 (10.2%) |

2234 (10.4%) |

1325 (8.4%) |

256 (11.1%) |

168 (9.1%) |

218 (9.1%) |

||||||||

|

Age (years), mean (SD)* |

15.2 (0.4) |

15.2 (0.4) |

15.2 (0.4) |

15.2 (0.4) |

15.3 (0.4) |

15.2 (0.4) |

15.3 (0.4) |

||||||||

|

Service events |

— |

234 008 |

51 350 |

140 916 |

15 983 |

14 333 |

11 426 |

||||||||

|

Socio‐economic position (IRSD quintile) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

1 (most disadvantaged) |

20 457 (23.6%) |

5056 (21.7%) |

4653 (21.6%) |

3117 (19.9%) |

435 (18.9%) |

401 (21.7%) |

531 (22.2%) |

||||||||

|

2 |

17 018 (19.6%) |

4564 (19.6%) |

4205 (19.5%) |

2960 (18.9%) |

424 (18.4%) |

367 (19.9%) |

458 (19.2%) |

||||||||

|

3 |

15 286 (17.6%) |

4095 (17.6%) |

3811 (17.7%) |

2762 (17.6%) |

387 (16.8%) |

334 (18.1%) |

429 (17.9%) |

||||||||

|

4 |

14 077 (16.2%) |

3930 (16.8%) |

3637 (16.9%) |

2732 (17.4%) |

379 (16.4%) |

308 (16.7%) |

420 (17.6%) |

||||||||

|

5 (least disadvantaged) |

19 921 (23%) |

5685 (24.4%) |

5229 (24.3%) |

4122 (26.3%) |

681 (29.5%) |

434 (23.5%) |

553 (23.1%) |

||||||||

|

Geographic remoteness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Major cities |

63 880 (73.6%) |

16 988 (72.8%) |

15 664 (72.7%) |

11 674 (74.4%) |

1690 (73.3%) |

1239 (67.2%) |

1760 (73.6%) |

||||||||

|

Inner regional |

16 879 (19.5%) |

4970 (21.3%) |

4600 (21.4%) |

3285 (20.9%) |

503 (21.8%) |

467 (25.3%) |

503 (21%) |

||||||||

|

Outer regional/remote/very remote |

6000 (6.9%) |

1372 (5.9%) |

1271 (5.9%) |

734 (4.7%) |

113 (4.9%) |

138 (7.5%) |

128 (5.4%) |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IRSD = Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage; SD = standard deviation. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Annual and cumulative incidence and numbers of service events for 86 759 New South Wales children who received Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)‐subsidised mental health care before their 15th birthday, 2002–18, by service type*

* Values of fewer than fifteen children are suppressed to preserve anonymity. The data underlying these graphs are included in the Supporting Information, table 3.

Box 3 – Associations between socio‐demographic characteristics and Medicare Benefits Schedule‐subsidised mental health care use by 86 759 New South Wales children before their 15th birthday, 2002–18: multivariable logistic regression analyses*

|

|

Adjusted odds ratios (99.924% confidence intervals†) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Any mental health service |

Better Access plan |

Psychologist |

Psychiatrist |

Occupational therapist or social worker |

Other services |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sex (boys) |

1.00 (0.95–1.06) |

0.92 (0.88–0.97) |

1.04 (0.98–1.10) |

1.12 (0.97–1.30) |

1.19 (1.01–1.40) |

2.70 (2.30–3.17) |

|||||||||

|

Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander people |

1.60 (1.46–1.76) |

1.62 (1.47–1.78) |

1.22 (1.09–1.36) |

1.66 (1.30–2.08) |

1.13 (0.84–1.48) |

1.22 (0.95–1.56) |

|||||||||

|

Age (31 December 2018, per year |

1.30 (1.21–1.40) |

1.25 (1.16–1.34) |

1.31 (1.21–1.43) |

1.39 (1.15–1.69) |

1.15 (0.93–1.43) |

2.00 (1.65–2.42) |

|||||||||

|

Socio‐economic position (IRSD quintile) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

1 (most disadvantaged) |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

2 |

1.11 (1.03–1.21) |

1.12 (1.03–1.21) |

1.14 (1.04–1.26) |

1.17 (0.93–1.48) |

1.11 (0.87–1.42) |

1.01 (0.81–1.25) |

|||||||||

|

3 |

1.12 (1.03–1.22) |

1.14 (1.05–1.24) |

1.20 (1.09–1.32) |

1.21 (0.95–1.53) |

1.15 (0.89–1.48) |

1.05 (0.84–1.32) |

|||||||||

|

4 |

1.19 (1.09–1.30) |

1.20 (1.10–1.31) |

1.30 (1.18–1.43) |

1.29 (1.01–1.64) |

1.17 (0.90–1.52) |

1.10 (0.88–1.38) |

|||||||||

|

5 (least disadvantaged) |

1.26 (1.16–1.36) |

1.25 (1.16–1.36) |

1.41 (1.29–1.55) |

1.70 (1.36–2.12) |

1.24 (0.97–1.59) |

1.02 (0.82–1.27) |

|||||||||

|

Geographic remoteness |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Major cities |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

Inner regional |

1.11 (1.04–1.19) |

1.12 (1.04–1.19) |

1.09 (1.01–1.18) |

1.14 (0.95–1.37) |

1.45 (1.19–1.75) |

0.98 (0.82–1.17) |

|||||||||

|

Outer regional/remote/very remote |

0.78 (0.70–0.88) |

0.79 (0.71–0.89) |

0.65 (0.56–0.75) |

0.73 (0.51–1.01) |

1.23 (0.88–1.67) |

0.70 (0.50–0.95) |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IRSD = Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage. * Results from univariable models are presented in the Supporting Information, table 2. † Bonferroni‐adjusted for multiple testing. |

|||||||||||||||

Received 23 November 2023, accepted 26 July 2024

- 1. Sawyer MG, Reece CE, Sawyer AC, et al. Access to health professionals by children and adolescents with mental disorders: are we meeting their needs? Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2018; 52: 972‐982.

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Medicare‐subsidised mental health‐specific services 2021–22; here: table MBS.2. Updated Apr 2023. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/174ffa67‐f355‐4512‐a3f4‐23222bfb700c/Medicare‐subsidised‐mental‐health‐specific‐2021‐22.xlsx (viewed Oct 2023).

- 3. Green MJ, Watkeys OJ, Harris F, et al. Cohort profile update: the New South Wales Child Development Study (NSW‐CDS), wave 3 (child age ∼18 years). Int J Epidemiol 2024; 53: dyae069.

- 4. Brinkman SA, Gregory TA, Goldfeld S, et al. Data resource profile: the Australian Early Development Index (AEDI). Int J Epidemiol 2019; 43: 1089‐1096.

- 5. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Index of Relative Socio‐economic Disadvantage (IRSD). In: Socio‐Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2021. 27 Apr 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people‐and‐communities/socio‐economic‐indexes‐areas‐seifa‐australia/latest‐release#index‐of‐relative‐socio‐economic‐disadvantage‐irsd‐ (viewed Oct 2023).

- 6. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC) 2006 (1216.0). 14 July 2006. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/1AEE5890BD5B7B5ECA2571A90017901F?opendocument (viewed Oct 2023).

- 7. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577.

- 8. Productivity Commission. Overview (here: fig. 6). In: Mental health: Productivity Commission inquiry report, volume 1 [No. 95]. 30 June 2020. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental‐health/report/mental‐health.pdf (viewed Aug 2021).

- 9. Bartram M, Stewart JM. Income‐based inequities in access to psychotherapy and other mental health services in Canada and Australia. Health Policy 2019; 123: 45‐50.

- 10. Hiscock H, Mulraney M, Efron D, et al. Use and predictors of health services among Australian children with mental health problems: a national prospective study. Aust J Psychol 2020; 72: 31‐40.

Data Sharing:

The data used in this study have been provided by government custodians for research purposes of the NSW Child Development Study and cannot be shared with third parties or deposited in data repositories. Researchers wishing to access these data need to apply in writing to the relevant data custodians.

The study was conducted at the University of New South Wales with financial support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (project grant APP1148055; Investigator grant APP1175408 to Kimberlie Dean), the Australian Research Council (Future Fellowship FT170100294 to Kristin Laurens), and the Department of Health and Aged Care Medical Research Future Fund (Million Minds Mental Health Grant APP2006436). Oliver Watkeys was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Suicide Prevention Australia. The funding bodies had no role in the planning, writing, or publication of the work, nor any role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, reporting or publication.

The New South Wales Child Development Study used population data owned by the NSW Department of Education; Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), managed by the NSW Education Standards Authority; the NSW Department of Communities and Justice; the NSW Ministry of Health; ACT Health; the NSW Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages; the Australian Coordinating Registry (on behalf of Australian Registries of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Australian coroners, and the National Coronial Information System); the Australian Bureau of Statistics; the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; the Australian Department of Social Services; the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, and the NSW Police Force. This research used data from the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC), which is funded by the Australian Department of Education. The findings and views reported are those of the authors and should not be attributed to these departments, nor to the NSW or Australian governments.

No relevant disclosures.