We all want children and young people to lead happy, healthy lives and to live better and longer than their parents. Yet, in Australia, children and young people are faring poorly in key health and wellbeing outcomes. For example, the number of children living in poverty1 or out‐of‐home care2 remains stagnant, while levels of overweight and obesity3 and psychological distress4 are increasing in young people. This is particularly apparent for those facing structural disadvantages (eg, economic and social) and complex needs (eg, young people with disabilities or with mental health issues, and survivors of abuse), as well as those affected by systemic injustice and intergenerational trauma, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and other marginalised groups.5 As a nation that claims to value children and young people, why are such profound health and wellbeing inequities allowed to exist? Addressing this fundamental problem requires Australians to demand change and engage with the big issues facing our children and young people. Importantly, it requires political will and policy attention on the health and wellbeing of our children and young people, with an eye to future generations.

The Future Healthy Countdown 2030 (the Countdown) builds on the breadth of existing work by key experts and advocates in children and young people's health and wellbeing, as outlined in its inaugural supplement framing article.6 It seeks to change outcomes for children and young people by stimulating citizen, political and policy will for action. The Countdown will provide an evidence‐based shortlist of achievable policy actions that, if actioned now, would improve outcomes for children and young people by 2030. Each year, it will track both key outcome measures targeted by these policy actions and the implementation of these policies. The Countdown aims to hold all Australians accountable, particularly those holding political and policy power, by spotlighting where progress has and has not been made.

The good news is that change is possible, as policy choices by those in power can advance equitable and sustainable health and wellbeing outcomes.7 However, the Australian policy landscape is complex, burdened by different jurisdictional responsibilities for legislation, policies, and funding. A recent analysis of 26 Australian child and youth health policies found only 10% addressed the social determinants of health, with governments continuing to adopt a siloed approach.8 Many solutions for improving health and wellbeing lie outside the health portfolio (eg, education, justice, and social services),9 requiring deep collaboration across government sectors. This could be enabled by a strong political mandate from the centre of governments (ie, Cabinets and coordinating bodies such as Departments of Prime Minister, Premier and Cabinet) to lead and legitimise efforts, as demonstrated in South Australia's Health in All Policies approach.10 A blueprint for change would highlight the co‐benefits and interconnectedness across government portfolios.

Several government roles advocate for children and young people, such as the federal Minister for Youth11 and federal, state and territory Children's Commissioners.12 However, their powers are limited in protecting children and young people's interests in new legislation or policies. Despite concerning data on their health and wellbeing, children and young people are not a key priority area for National Cabinet,13 nor are the Youth and Early Childhood Education portfolios included in Cabinet (they currently sit in the outer Ministry).11 This prevents both inter‐ and intra‐government planning around the longer term interests of young Australians, including those not yet born. Potential policy mechanisms to manage this issue include legislation to protect the rights of children, young people and future generations, such as enshrining the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (https://www.unicef.org.au/united‐nations‐convention‐on‐the‐rights‐of‐the‐child).

Still, there are some reasons for renewed optimism, with certain government initiatives bringing focus both on children and young people and having more meaningful and broad measures of success. Examples include the Australian Government's Early Years Strategy (0–5 years; 2024–2034),14 the Wellbeing Framework for Measuring What Matters15 and the recent Engage! strategy,16 which seeks to have more young people involved in decision making. However, unless deeply embedded across all portfolios with a mechanism for accountability, these efforts will likely fail.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic showed us the power of policies in shaping our nation: people were lifted out of poverty and inequalities were reduced through targeted government policies.17,18,19 Inequities are not inevitable but are shaped by conscious policy decisions. For example, it is a choice by those in power to subsidise fossil fuel producers and major users by $14.5 billion in a single financial year (2023–2024).20 Yet, they choose not to provide the $6.8 billion per annum needed to fund all public schools to the bare minimum (ie, 100% of the Schooling Resource Standard [SRS] for 2025).21 It is time for those in power to prioritise the health and wellbeing of our children and young people.

Developing a blueprint for action: a consensus building approach

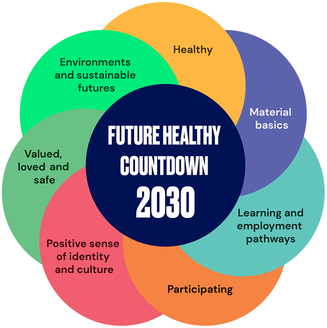

In 2023, we outlined the process of developing the framework for the Countdown in our inaugural MJA supplement.6 This involved reviewing 16 state, territory, national and international frameworks for the health, wellbeing and development of children and young people. We adopted “The Nest”, an evidence‐based framework developed by the Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY)22 in consultation with over 4000 Australians, including children and young people. The Nest identifies six interconnected domains that need to be adequately resourced for a young person (0–24 years) to thrive. We added a seventh domain (Environments and sustainable futures) because of the increasing impact of climate change on children and young people's health and wellbeing.23 These seven domains (Box 1) are the focus of the Countdown and its core policy actions.

In the inaugural supplement, Australia's leading experts outlined the most pressing issues for children, young people and future generations in these domains — those where change could make a real difference by 2030.6 In addition, they proposed a number of measures to track progress on these changes and drive accountability. In this consensus statement, we operationalise the Countdown into an actionable and clear blueprint for implementation for all of us to follow between now and 2030.

We focus on one high level policy action per domain that could improve health and wellbeing for children and young people by 2030. A consensus‐building process determined the policy actions most likely to achieve significant improvement within each domain and accompanying accountability measures. This has resulted in a set of high level trackable policy actions that are highly interconnected across the domains, that together cover age 0–24 years. These policy actions can be done now and have a strong evidence base for improving health and wellbeing now and with benefits into the future.

Consensus‐building methods

The Countdown is collaboratively led by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, the Murdoch Children's Research Institute and ARACY. Representatives of each of these organisations, policy experts and key stakeholder representatives sit on the Countdown Steering Committee, which has strong connections across the country.

We invited all the experts who led the inaugural supplement in 2023, as well as additional key subject matter policy experts and young people with lived experience, to participate in a multistep process to build consensus. A consensus was sought to determine a suite of policy actions (one per Countdown domain) and appropriate measures for tracking progress in the lead‐up to 2030.

The consensus‐building process was coordinated by the Countdown Steering Committee and involved three steps: (i) a survey, (ii) a workshop, and (iii) a final process, led by the Steering Committee, to bring together a suite of consensus policy actions and measures for implementation in the Countdown.

Consensus building survey

A short survey was sent to 61 experts in March 2024. Experts were assigned to one of the seven domains based on their area of expertise. In total, 50 individuals (82%) completed the survey. Response rates for each domain varied from 60% (positive sense of identity and culture) to 100% (healthy). Demographic data for the survey participants are detailed in Box 2. The expertise of the group spanned research expertise (38%), policy expertise (24%) and the lived experience of young people (24%).

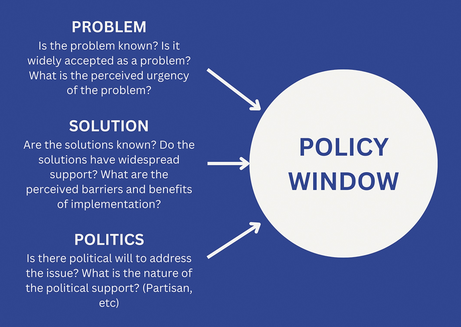

Survey participants were provided with a link to the expert paper from the 2023 inaugural Supplement outlining the most pressing issues facing children, young people and future generations in their assigned domain. They were also given the “policy window” criteria to guide policy prioritisation and decision making. These criteria were drawn from Kingdon's multiple streams approach (Box 3), which argues that a window for policy change opens when the following exist: a problem is widely understood and accepted by experts, government, and community; solutions are available, supported and feasible; and there is political will (ie, motive and opportunity) to deal with the issue.24

Based on these criteria, participants were asked to identify one key policy action for their assigned domain that would improve the health and wellbeing of today's children and young people (aged 0–24 years) within the next six years and build a strong foundation for future generations.

Participants were also asked to suggest key measures (available and/or unavailable) that would best track progress for their policy action from now until 2030. Evidence‐based selection criteria were provided, including that measures be relevant, applicable across population groups, technically sound, feasible to collect and report, timely, marketable, and lead to action.25

Workshop

The Consensus‐Building Workshop (the Workshop) was held online via Zoom with 38 experts who completed the survey (nine young people, eight policy experts and 21 researchers). Summarised survey results were distributed beforehand. During the Workshop, participants were assigned to breakout rooms within their domain group to prioritise one policy action they collectively deemed most important to include and measure for the Countdown. In another breakout session, they selected appropriate measures to track progress on the identified policy action.

At the Workshop, a significant challenge identified for all domains was the absence of a legislative mechanism compelling government decision makers to prioritise the needs of children and young people, now and into the future. It was noted that decisions made today will affect the lives of future generations, yet future generations are not formally considered in current decision‐making processes. Therefore, experts at the Workshop also discussed an overarching policy action to address this. Two mechanisms were discussed: Children in All Policies, and a Future Generations Commission/er.

Steering Committee consensus

Following the Workshop, the Countdown Steering Committee considered all policy actions and measures to ensure they were complementary across domains. Some policy actions reached immediate consensus after the Workshop whereas others required more consultation with domain experts to reach a final consensus. Different criteria were considered, including the age range that would most benefit from each policy action, the compatibility of policy actions to one another across domains, and a balance of new policy asks and increased investment. Appetite for various policy actions was also weighed. Ultimately, the Committee selected policy actions that offered the most realistic and impactful systems‐level national changes while building on current momentum. The final suite of seven domain‐based policy actions and one overarching action (a Future Generations Commission) is listed in Box 4.

Other key policy actions that were debated and warrant acknowledgement include:

- more curriculum‐enforced physical activity in schools for the Healthy domain;

- a coalition model between public, independent and private schools to work together locally in place‐based communities to gather student feedback and find solutions for the Learning and employment pathways domain;

- a healthy schools approach that has clear policies and approaches for victimisation based on identity or culture and includes a broader curriculum that enables young people to express their identity and culture for the Positive sense of identity and culture domain; and

- embedding policies to genuinely engage young people in leadership positions across sectors for the Participating domain.

These policies are each worthy of action, but we chose systems‐based policy actions where the likely impact was perceived to be greater. For each domain, we outline the policy action identified, the issue, the rationale for this choice, and the measures we will use to track progress.

Material basics

Recommended policy action

Provide financial support to invest in families with young children and address poverty and material deprivation in the first 2000 days of life.

Issues

The cost of living is one of the greatest challenges facing families today.26 An increasing proportion of Australian families is experiencing material deprivation (Box 5), meaning they are unable to afford the material basics that are essential for health and wellbeing. Material deprivation increases as household income decreases.30 Children raised in families experiencing material deprivation or poverty are more likely than other children to experience socio‐emotional difficulties, physical health problems and chronic disease, educational difficulties and poor mental health.30,31,32

Rationale

Money matters for child development. During the first 2000 days of life, the human brain develops rapidly, laying the foundation for ongoing health and development.33 Financial hardship can disrupt this foundational period and undermine health and development.34 Increasing household income in the first years of life is a well established investment with long term benefits for human development.35 Investment in this period benefits both individual outcomes and society by decreasing health service and education costs and boosting education and economic outcomes.36 Societies that front‐end their investment by spending more on childhood are healthier.34 Providing a financial investment or so‐called boost to families facing tough times leverages existing political momentum and aligns with the demands of peak bodies37 advocating for our children to have equitable starts to life. Current government policy agendas,15 strategies38,39 and action plans,40,41 including the Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care (SNAICC)‘s National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children,37 all point to the urgent need for early intervention and targeted support for children and families experiencing disadvantage.

Valued, loved and safe

Recommended policy action

Establish a national investment fund to provide sustained, culturally relevant, maternal and child health and development home visiting services for the first 2000 days of life for all children facing structural disadvantage and/or adversity.

Issues

Children and young people who are valued, loved and safe have the foundations to thrive.42 These aspects are particularly important for attachment and relational health, which develop early in life.43 Feeling love and safety from care providers plays a critical role in supporting health and wellbeing during the first 2000 days of life and across the early life course.42 Children who lack these essential components too often experience neglect and abuse (ie, maltreatment), both of which have profound effects on their development, health and wellbeing.44 Sustained maternal home health visiting that begins antenatally, and is culturally appropriate,45 can help facilitate relationships and trust with health professionals and access to support services. This can support early identification and response to potential and actual risks to the health and safety of infants and children.44,46 To succeed and avoid harm, services must be culturally relevant and, where appropriate, community‐controlled.

Rationale

Children from families facing structural disadvantage and/or adversity can lack opportunities for positive interaction with parents for many reasons, including financial demands limiting time and relational stressors. They are also more likely than other children to start school developmentally behind.46 These families need easy access to targeted maternal home‐visiting services to help ensure their children have the best chance to thrive. Evidence‐based services can improve child and parental health and wellbeing and enhance family functioning,45,47 are cost‐effective and ultimately help reduce health inequities.46 A national investment fund would ensure services to all families facing structural disadvantage or adversity, which would be delivered in collaboration with state and territory services. Currently, the only available nationally consistent measures of children's nurturing and safety are the rate of children on care and protection orders and in out‐of‐home care, which reflect children already at risk (Box 6). The Australian Early Development Census provides a measure of early development, health and wellbeing through a national three‐year assessment of young children.

Healthy

Recommended policy action

Establish legislation and regulation to protect children and young people aged under 18 years from the marketing of unhealthy and harmful products.

Issue

Two of the biggest current issues for Australian children and young people's health and wellbeing are persistently high rates of common mental disorders (almost two in five young people aged 16–24 years experienced a mental disorder within the past 12 months)4 and challenges maintaining a healthy weight (one in four children/adolescents and two in five young adults experience overweight or obesity) (Box 7).3 Mental disorders and weight problems are also more common for those facing structural disadvantage or adversity.53 Both problems are strongly grounded in the commercial determinants of health,54 where big businesses leverage considerable resources and political power to market harmful or addictive products (eg, ultraprocessed foods, alcohol, vaping, and gambling products) to ensure continued economic growth.55 Children and young people need protection from predatory marketing while they develop impulse control and skills to understand its persuasive intent.56 More far‐reaching than traditional advertising is the rise of digital predatory marketing, which includes the use of “kidfluencers”, where marketers recruit parents and children with social media reach to endorse products and promote brands to other children.57,58

Rationale

Predatory marketing of unhealthy and harmful products is a major commercial determinant of health for children and young people.54,59 These marketing practices often target those facing structural disadvantage, further exacerbating health inequities.60,61 Regulating the marketing (particularly digital marketing via social media platforms) of harmful products is crucial to protecting children and young people's health. Several national and international organisations are among those advocating for this urgent change.62 In addition, the Australian Government has agreed in principle to digital marketing reforms that protect children through its response to the Privacy Act Review.63

Learning and employment pathways

Recommended policy action

Properly fund public schools, starting by providing full and accountable Schooling Resource Standard (SRS) funding for all schools, with immediate effect for schools in communities facing structural disadvantage.

Issues

In Australia, the gap between our richest and poorest students is firmly entrenched and worsening over time.64 Equity of education has strong associations with individuals’ life expectancy, morbidity and health behaviour, and educational attainment is important to people's health in shaping their further education, employment, and success in life.65 Yet, increasing amounts of government funds have been funnelled, directly and indirectly, into private and religious schools through generous tax deductions, including donations from wealthy benefactors.66 These concessions not only leave public schools chronically underfunded, but provide a fiscal basis for maintaining a class structure within Australian society that perpetuates cross‐generational cycles of inequities.66 It is not surprising that student learning, health and wellbeing do not flourish in this unequal and unfair educational environment (Box 8).69

Rationale

Public schools are vastly underfunded in terms of the SRS, which is an estimate of how much total public funding a school needs to meet its students’ educational needs.21 This puts efforts to keep the promise made in the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration70 at risk in most disadvantaged schools and communities. Calculated to get at least 80% of students above the minimum standard for NAPLAN (National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy) testing, the SRS is the bare minimum rather than a lofty aspiration.71 The Australian Government has committed to fund all public schools to 100% of the SRS by 2029. Currently, only the Australian Capital Territory has all public schools fully funded, and Western Australia and the Northern Territory have recent agreements to do so by 2029,72 which is too late for those needing it now. Government funding to public schools must adopt a staggered rollout (place‐based segregation) that primarily targets communities with urgent socio‐educational needs now.

Participating

Recommended policy action

Amend the electoral act to extend the compulsory voting age to 16 years.

Issue

Children and young people, especially those from under‐represented communities, have limited power in decision‐making processes.73 The exclusion of children and young people's voices from policies such as climate change,74 policies that increase wealth inequality (eg, negative gearing),75 and the COVID‐19 pandemic76 has often led to retrospective regret, reactive measures, and detrimental effects on their current and future wellbeing. Despite being most acutely affected by these critical issues, their concerns are often overlooked due to the expediency of short term political decision making. This hinders the development of proactive and preventive policies needed to support the long term health and wellbeing of children and young people across generations.

Rationale

Voting is a political determinant of health, particularly for marginalised groups who are more likely to face health disparities and policy neglect and have decreased access to voting.77 Extending the voting age to 16 years would acknowledge young people's basic democratic right to contribute to decisions that have an impact on their lives,78 promote civic engagement among youth, and strengthen the democratic foundations of our electoral system (Box 9).81,82 It would amplify their unique insights into the health challenges they face and how governments should respond83 and encourage politicians to better align their policies with young people's concerns. Ultimately, this would promote more balanced investments in different ages and generations, including health strategies that are both preventive and proactive.77 Initiatives such as the “Make It 16” campaign, led by young people advocating for extending the voting age, exemplify young people's desire for direct political participation to ensure their perspectives shape policies affecting their health and wellbeing.84

Positive sense of identity and culture

This section summarises information from SNAICC — National Voice for our Children's recent Funding model options for ACCOs [Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community‐Controlled Organisations] integrated early years services, final report,85 with their permission.

Recommended policy action

Implement a dedicated funding model for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled early years services across the country to ensure these services are fully resourced to provide quality early learning and integrated services grounded in culture and community.

Issues

Participation in quality early learning environments has a positive impact on a child's life outcomes and supports them to realise their full potential. Culture is a critical part of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children's development, identity and self‐esteem and strengthens their overall health and wellbeing. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and families to experience cultural safety, early years services must be grounded in cultural frameworks that reflect the protocols and practices of local families and communities.

Rationale

ACCOs have offered holistic early childhood support for decades, continuing practices of nurturing care for children that have been central to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures for millennia. These early learning services go well beyond the mainstream scope of childcare and early education to provide holistic wrap‐around support for children, extended families and communities. They address gaps in the availability of culturally safe services, provide children with opportunities to grow up strong in their cultures and identities, and support families to navigate government and non‐Indigenous service systems across areas including health, disability, social and community services. Current early childhood education and care funding models in Australia are predominantly individual child focused and market‐driven, failing to provide for the whole of family and whole of community focus that is critical to overcoming the ongoing impacts of colonisation, racism and discrimination for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families. Recent research by SNAICC, supported by economic modelling by Deloitte Access Economics, has recommended a dedicated funding model for ACCO early years services that incorporates block‐based, needs‐based and backbone support funding from a single funding source, coordinated between the Commonwealth, state and territory governments. Funding would be scaled up based on population, levels of community need, and the impacts of remoteness in each community, and would also include infrastructure planning to address gaps in service availability across the country. Reforming the funding model for ACCO early years services will enable these services to continue and grow to deliver holistic, wraparound services grounded in culture that support the positive identity, wellbeing and development of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (Box 10).

Environments and sustainable futures

Recommended policy action

Legislate an immediate end to all new fossil fuel projects in Australia.

Issues

Climate change, ecological degradation, migrating populations, conflict, and pervasive inequalities threaten the health and future of children and young people in every country.59 Worldwide, children will be most affected by disaster events, with an estimated one billion at extreme risk of experiencing negative impacts because of climate change and associated disasters.86 The goal of keeping global warming under 1.5°C is almost lost, with leading scientists expecting current projections to be 3°C or greater with catastrophic impacts.87 It is notable that Australia is warming faster than other parts of the world — our average temperature increased by 1.44°C (standard deviation, 0.24°C) between 1910 and 2019.88 Under the current climate projections, heatwaves in Australia will increase between 29‐fold and 42‐fold by the end of the century.89

Australia ranks particularly poorly in terms of its climate policies and actions.90 For example, our consumption‐based carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions since the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997 were 14.8 tonnes per person per year, shamefully ranking us 39 out of 43 economically advanced countries.91 It is no wonder that most 18–24‐year‐olds (66%) do not think the federal government is doing enough to prepare and adapt to climate impacts.92

Rationale

The largest contributor to CO2 emissions is burning fossil fuels,93 resulting in calls from the International Energy Agency,94 the United Nations,95 and leading scientists in Australia96 and around the world97 to end new fossil fuel development. Yet, the Australian Government continues to support the development of new coal, oil and gas projects in Australia (Box 11). Projects scheduled to begin before 2030 alone will add a further 1.4 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere annually until 2030.100 In 2023–2024, all Australian governments subsidised fossil fuel producers and major users by $14.5 billion, an increase of 31% in one year.20 Preventing any further new fossil fuel projects would not only help achieve genuine reductions in emissions but would save money that could be spent on transitions to clean energy,20 which is critically underfunded.90 This is essential if we want a habitable world for our young and future generations.

Overarching policy action

Recommended policy action

Establish a federal Future Generations Commission with legislated powers to protect the interests of future generations.

Issue

In their Declaration on Future Generations, the United Nations recognises the need to safeguard the interests of future generations.101 However, no government department or level of government is accountable for Australia's future generations, which often results in policy decisions lacking long term vision for short term economic gain.102,103 A recent survey of 1000 Australian adults found that 97% think current policies should consider the interests of future generations.104 Considering future generations in policies is also a tool for serving the needs of children and young people today as longer term vision will likely benefit them as they mature.105

Rationale for policy action

Many are advocating for a Future Generations Commission to ensure long term vision as a necessity of public policy, this includes parliamentarians (eg, Parliamentary Group for Future Generations)106 and organisations (eg, the Intergenerational Fairness Coalition).107 In Wales, the world's first Future Generations Commissioner108 was appointed to act as a guardian for the interests of future generations and to support the public bodies listed in the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015.109,110 This position led to major reforms across portfolios in Wales, including transport planning, education and climate change. To ensure such a system could work in Australia requires the existence of legislative powers across portfolios to protect future generations. Consultation is underway across civil society and government to determine the best mechanism within Australia to do this. For instance, the Intergenerational Fairness Coalition107 has called for the establishment of a Commission but continues to consider the best legislative structure to protect the wellbeing of future generations. This could be a Commission or a Commissioner.107

Potential measure

A Future Generations Budget, modelled on the Women's Budget Statement, would provide an annual tracker of progress.

Conclusion

Together, these evidence‐based achievable policies would substantially improve children and young people's health and wellbeing by 2030. They also build a strong foundation for future generations and provide co‐benefits for all generations and society. Each year, in the MJA Future Healthy Countdown 2030 Supplement, as well as reporting on the Countdown's progress, we intend to produce a series of articles focusing on one of the seven domains of children and young people's health and wellbeing. Each supplement will detail the issues and solutions for the domain to lay out the evidence base for action and drive advocacy. We hope the Countdown will help citizens advocate for change and ultimately hold politicians and policy makers accountable for their choices to value, or not to value, children and young people in our society.

Box 1 – The domains of the Future Healthy Countdown 2030 Framework

Source: Image reproduced from Lycett et al.6

Box 2 – Demographic data of survey participants

|

Demographic characteristics |

n (%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of participants |

50 |

||||||||||||||

|

Gender identity* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Female |

31 (63%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Male |

16 (33%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Non‐binary |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Prefer not to say |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Primary area of expertise |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Researcher |

19 (38%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Policy expert |

12 (24%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Young person |

12 (24%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Clinician |

2 (4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other |

5 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Age group* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

18–25 |

9 (19%) |

||||||||||||||

|

26–30 |

6 (13%) |

||||||||||||||

|

31–50 |

22 (47%) |

||||||||||||||

|

≥ 51 |

10 (21%) |

||||||||||||||

|

State |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Victoria |

32 (64%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Australian Capital Territory |

5 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Western Australia |

5 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Queensland |

4 (8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

New South Wales |

3 (6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

South Australia |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Cultural background* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Australian (excluding Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander) |

24 (49%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

3 (6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Anglo and North‐West European |

10 (21%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Sub‐Saharan African |

3 (6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

South‐East Asian |

3 (6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Southern and Central Asian |

2 (4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Māori, Melanesian, Papuan, Micronesian and Polynesian |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

South‐East European |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other cultural/ethnic group |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Prefer not to say |

1 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Respondents for each domain |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Material basics |

9 (18%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Healthy |

8 (16%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Environments and sustainable futures |

8 (16%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Learning and employment pathways |

7 (14%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Participating |

6 (12%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Positive sense of identity and culture |

6 (12%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Valued, loved and safe |

6 (12%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Demographic item had missing data. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Policy actions

|

Domain |

Policy action |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Overarching |

Establish a federal Future Generations Commission with legislated powers to protect the interests of future generations. |

||||||||||||||

|

Material basics |

Provide financial support to invest in families with young children and address poverty and material deprivation in the first 2000 days of life |

||||||||||||||

|

Valued, loved and safe |

Establish a national investment fund to provide sustained, culturally relevant, maternal and child health and development home visiting services for the first 2000 days of life for all children facing structural disadvantage and/or adversity. |

||||||||||||||

|

Positive sense of identity and culture |

Implement a dedicated funding model for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled early years services across the country to ensure these services are fully resourced to provide quality early learning and integrated services grounded in culture and community. |

||||||||||||||

|

Learning and employment pathways |

Properly fund public schools, starting by providing full and accountable Schooling Resource Standard funding for all schools, with immediate effect for schools in communities facing structural disadvantage. |

||||||||||||||

|

Healthy |

Establish legislation and regulation to protect children and young people aged under 18 years from the marketing of unhealthy and harmful products. |

||||||||||||||

|

Participating |

Amend the electoral act to extend the compulsory voting age to 16 years. |

||||||||||||||

|

Environments and sustainable futures |

Legislate an immediate end to all new fossil fuel projects in Australia. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Domain: Material basics — tackling poverty and material deprivation

|

Target |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

As per the Sustainable Development Goals, halve poverty by 2030 (SDG target 1.2)27 |

Proportion of 0–24‐year‐olds living in poverty |

2021: 12% |

Australian Census, Australian Bureau of Statistics28 |

||||||||||||

|

Proportion of 0–24‐year‐olds who are experiencing housing stress, overcrowding or homelessness |

2021:

|

Australian Census, Australian Bureau of Statistics28 |

|||||||||||||

|

Proportion of 15–24‐year‐olds not in employment, education or training |

2021: 10% |

Australian Census, Australian Bureau of Statistics28 |

|||||||||||||

|

Proportion of caregivers of children (0–17 years of age) reporting material deprivation |

2023: 35% |

Royal Children's Hospital National Child Health Poll29 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Domain: Valued, loved and safe — supporting marginalised and disadvantaged children

|

Targets |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The gap between children living in the most and least socio‐economically disadvantaged communities who are developmentally on track at school entry in all five domains |

2021: 21%* |

Australian Early Development Census48 |

||||||||||||

|

Rate of 0–17‐year‐olds on care and protection orders, per 1000 children |

2023:

|

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare2 |

|||||||||||||

|

Rate 0–17‐year‐olds in out‐of‐home care, per 1000 children |

2023:

|

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare2 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* 42.7% on track in the most disadvantaged quintile versus 63.4% on track in the least disadvantaged quintile. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Domain: Healthy — addressing mental health and obesity

|

Targets |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and young people |

2022:

|

National Health Survey (ABS)3 |

||||||||||||

|

Prevalence of mental health distress and disorders in 4–17‐year‐olds |

2013: 20% (high/very high distress) and 14% (disorder) |

Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing52 |

|||||||||||||

|

Prevalence of mental health distress and disorders in 16–24‐year‐olds |

2020–2022: 26% (high/very high distress) and 39% (disorder) |

National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing (ABS)4 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ABS = Australian Bureau of Statistics. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 8 – Domain: Learning and employment pathways — properly funding public schools

|

Targets |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Proportion of public schools fully funded to a bare minimum (100% of the SRS) by 2027 |

2023: 1% |

Review of Better and Fairer Education System67 |

||||||||||||

|

Proportion of Australian students attending a school with high concentrations of socio‐educationally disadvantaged students |

2022: 14% |

Review of the National School Reform Agreement — study report68 |

|||||||||||||

|

Change in literacy and numeracy achievement gaps between socio‐educationally advantaged students as they progress from Year 3 to Year 9 |

2021: 1.9–4.9 years (reading); 1.3–3.7 years (numeracy) |

Australian Curriculum, Assessments and Reporting Authority68 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 9 – Domain: Participating — extending the voting age to 16 years

|

Target |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Amendment of the Electoral Act to reduce the compulsory federal voting age to 16 years |

The proportion of young people aged 16–18 and 18–24 years enrolled to vote |

June 2024: 0% and 90% |

Australian Electoral Commission79 |

||||||||||||

|

The proportion of young people aged 15–19 years participating in political groups and activities |

2023: 3% |

Annual Mission Australia Youth Survey80 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 10 – Domain: Positive sense of identity and culture — implementing a funding model for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community‐controlled early years services

|

Closing the Gap targets |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children assessed as developmentally on track in all five domains of the AEDC |

2021: 34% |

Closing the Gap Information Repository – Productivity Commission49 |

||||||||||||

|

The number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander‐focused integrated early years services that are ACCOs |

2023: 107 |

Closing the Gap Information Repository – Productivity Commission49 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AEDC = Australian Early Development Census; ACCOs = Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community‐Controlled Organisations. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 11 – Domain: Environments and sustainable futures — legislating an immediate end to all new fossil fuel projects

|

Target |

Available measures |

Baseline data |

Source |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

No new fossil fuel (coal, oil or gas) projects scheduled to begin development that are funded by any Australian government |

Number of new coal, oil and gas projects expected to begin production by 2030 |

2023: 92 |

Australian Government Resources and Energy Major Projects (REMP) list98 |

||||||||||||

|

Year‐on‐year change in CO2 emissions |

2022 to 2023: 5.67 million tonnes (increase) |

Australia: CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions (Our World in Data)93 |

|||||||||||||

|

Annual percentage of Australia's electricity produced through renewable sources |

2023: 36% |

Australia: Energy (Our World in Data)99 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CO2 = carbon dioxide. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Kate Lycett1,2

- Hannah Lane2

- Georgie Frykberg1,2

- Susan Maury3

- Carolyn Wallace3

- Luisa Taafua3

- Bernie Morris4

- Anne Hollonds5

- Pasi Sahlberg6

- Kevin Kapeke3

- Ngiare Brown7

- Jordan Cory6

- Peter D Sly8

- Craig A Olsson1,9

- Fiona J Stanley10,11

- Anna M H Price2,12

- Planning Saw6,13

- Khalid Muse14

- Peter S Azzopardi9

- Susan M Sawyer6,9

- Rebecca Glauert15,16

- Marketa Reeves15

- Roslyn Dundas4

- Sandro Demaio3,16

- Rosemary Calder17

- Sharon R Goldfeld2,6

- 1 SEED Lifespan Strategic Research Centre, Deakin University, Geelong, VIC

- 2 Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, Melbourne, VIC

- 4 Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY), Canberra, ACT

- 5 Australian Human Rights Commission, Sydney, NSW

- 6 University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 7 South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, SA

- 8 Child Health Research Centre, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 9 Centre for Adolescent Health, Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC

- 10 Kids Research Institute Australia, Perth, WA

- 11 University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 12 Murdoch Children's Research Institute, Melbourne, VIC

- 13 Global Health Youth Connect, Melbourne, VIC

- 14 Global Centre for Preventive Health and Nutrition, Deakin University Institute for Health Transformation, Melbourne, VIC

- 15 Australian Child and Youth Wellbeing Atlas, University of Western Australia, Perth, WA

- 16 Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 17 Mitchell Institute, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC

This article is part of the 2024 MJA supplement on the Future Healthy Countdown 2030, which was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) — a pioneer in health promotion that was established by the Parliament of Victoria as part of the Tobacco Act 1987, and an organisation that is primarily focused on promoting good health and preventing chronic disease for all. A number of authors are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Investigator grants, including Sharon Goldfeld (2026264), Susan Sawyer (1196999), Craig Olsson (APP1021480), Peter Azzopardi (2008574), Pasi Sahlberg (APP1193840).

VicHealth played a role in scoping and commissioning the articles contained in the supplement. NHMRC funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We thank all the experts who gave up their time to complete the survey and attend the Consensus Building Workshop.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Australian Council of Social Service and University of New South Wales. Poverty in Australia 2023: who is affected — poverty and inequality partnership report. Sydney: ACOSS and UNSW, 2023. https://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/poverty‐in‐australia‐2023‐who‐is‐affected (viewed July 2024).

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Child protection Australia 2022–23 [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2024. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child‐protection/child‐protection‐australia‐insights/contents/insights/supporting‐children (viewed July 2024).

- 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Waist circumference and BMI [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health‐conditions‐and‐risks/waist‐circumference‐and‐bmi/latest‐release (viewed June 2024).

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing 2020–2022 [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental‐health/national‐study‐mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing/latest‐release (viewed July 2024).

- 5. Noble K, Rehill P, Sollis K, et al. The wellbeing of Australia's children. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth and UNICEF Australia, 2023. https://assets‐us‐01.kc‐usercontent.com/99f113b4‐e5f7‐00d2‐23c0‐c83ca2e4cfa2/7157d4c1‐214f‐4539‐8fd7‐eedb9876b6a8/Australian‐Childrens‐Wellbeing‐Index‐Report_2023_for%20print.pdf (viewed Oct 2024).

- 6. Lycett K, Cleary J, Calder R, et al. A framework for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030: tracking the health and wellbeing of children and young people to hold Australia to account. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S3‐S10. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/framework‐future‐healthy‐countdown‐2030‐tracking‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐children

- 7. Woodward A, Kawachi I. Why reduce health inequalities? J Epidemiol Community Health 2000; 54: 923‐929.

- 8. Littleton C, Reader C. To what extent do Australian child and youth health, and education wellbeing policies, address the social determinants of health and health equity?: a policy analysis study. BMC Public Health 2022; 22: 2290.

- 9. World Health Organization. Adelaide Statement II on Health in All Policies. Adelaide: WHO, 2017. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/331585/WHO‐CED‐PHE‐SDH‐19.1‐eng.pdf?sequence=1 (viewed July 2024).

- 10. Southgate Institute for Health Society and Equity. Does a Health in All Policies approach improve health, wellbeing and equity in South Australia? Adelaide: Flinders University. https://www.flinders.edu.au/content/dam/documents/research/southgate‐institute/hiap‐policy‐brief.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 11. Australian Government. Outer Ministry. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.directory.gov.au/commonwealth‐parliament/outer‐ministry (viewed Oct 2024).

- 12. Office for the NSW Advocate for Children and Young People (ACYP). Australian commissioners and guardians [website]. Sydney: ACYP. https://www.acyp.nsw.gov.au/about/australian‐commissioners‐and‐guardians (viewed June 2024).

- 13. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Australia's federal relations architecture. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://federation.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐06/federal‐relations‐architecture_0.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 14. Australian Government. Early Years Strategy 2024–2034. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2024/early‐years‐strategy‐2024‐2034.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 15. Australian Government. Measuring what matters: Australia's first Wellbeing Framework. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐07/measuring‐what‐matters‐statement020230721_0.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 16. Australian Government, Department of Education. Engage! A strategy to include young people in the decisions we make. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.youth.gov.au/engage/resources/engage‐our‐new‐strategy‐include‐young‐people‐decisions‐we‐make (viewed July 2024).

- 17. Jericho G, Heap L, Joyce C, et al; editors. Briefing paper: Commonwealth budget 2024–25: important progress, missed opportunities. Canberra: Australia Institute, 2024. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/05/CFW‐Budget‐Brief‐2024‐25‐Formatted.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 18. Australian Government, Productivity Commission. A snapshot of inequality in Australia — research paper. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/inequality‐snapshot/inequality‐snapshot.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 19. Klein E, Cook K, Maury S, Bowey K. An exploratory study examining the changes to Australia's social security system during COVID‐19 lockdown measures. Aust J Soc Issues 2022; 57: 51‐69.

- 20. Campbell R, Morison L, Ryan M, et al. Fossil fuel subsidies in Australia 2024: federal and state government assistance to major producers and users of fossil fuels in 2023–24. Canberra: Australia Institute, 2024. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/05/P1543‐Fossil‐fuel‐subsidies‐2024‐FINAL‐WEB.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 21. Australian Government, Department of Education. Schooling Resource Standard [website]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.education.gov.au/recurrent‐funding‐schools/schooling‐resource‐standard#:~:text=The%20Schooling%20Resource%20Standard%20(SRS,to%206%20needs%2Dbased%20loadings (viewed July 2024).

- 22. ARACY – Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. What's in the Nest? An initiative of ARACY, 2024. Canberra: ARACY, 2024. https://www.aracy.org.au/the‐nest‐wellbeing‐framework/ (viewed Oct 2024).

- 23. Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, et al. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet Health 2021; 5: e863‐e873.

- 24. Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies, 2nd ed. New York: Longman, 1995; p 254.

- 25. Brockway I. Key indicators of progress for chronic disease and associated determinants: data report [Cat. No. PHE 142]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic‐disease/key‐indicators‐of‐progress‐for‐chronic‐disease/summary (viewed July 2024).

- 26. Australian Council of Social Service. Poverty and inequality in Australia: ACOSS Community of Leaders Report. Sydney: ACOSS, 2023. https://www.acoss.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/09/ACOSS_COL_Report_Sep_2023_Web.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 27. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 1: end poverty in all its forms everywhere [website]. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal1#targets_and_indicators (viewed June 2024).

- 28. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Microdata and TableBuilder: Census of Population and Housing. Canberra: ABS, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/microdata‐tablebuilder/available‐microdata‐tablebuilder/census‐population‐and‐housing (viewed July 2024).

- 29. Gamarra Rondinel A, Price A. Spend now, save later on poverty‐curbing policies. The Mandarin 2024, 1 May. https://www.themandarin.com.au/245311‐spend‐now‐save‐later‐on‐poverty‐curbing‐policies/

- 30. Sollis K. Measuring child deprivation and opportunity in Australia. Canberra: Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth, 2019. https://www.aracy.org.au/publication‐resources/command/download_file/id/384/filename/ARACY_Measuring_child_deprivation_and_opportunity_in_Australia.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 31. Saunders P, Bedford M, Brown J, et al. Material deprivation and social exclusion among young Australians: a child‐focused approach (SPRC Report 24/18). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, University of New South Wales; 2018. https://doi.org/10.26190/5bd2aacfb0112 (viewed June 2024).

- 32. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2018. Sydney: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias‐health/australias‐health‐2018/contents/table‐of‐contents (viewed June 2024).

- 33. Chung A, Hall A, Brown V, et al; Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. Why invest in prevention in the first 2000 days? 2022. https://preventioncentre.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2022/08/First‐2000‐days‐Policy‐Brief‐FINAL.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 34. Dominic R, David H, Sophie M, John H. Too little, too late: An assessment of public spending on children by age in 84 countries. 2023. Florence: Florence: UNICEF Innocenti — Office of Research, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/2851/file/UNICEF‐Too‐Little‐Too‐Late‐Report‐2023.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 35. Cooper K, Stewart K. Does household income affect children's outcomes? A systematic review of the evidence. Child Ind Res 2021; 14: 981‐1005.

- 36. Chan M, Lake A, Hansen K. The early years: silent emergency or unique opportunity? Lancet 2017; 389: 11‐13.

- 37. Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care. Safe and Supported: the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2021–2031. Canberra: Department of Social Services, 2021. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/01_2023/final_aboriginal_and_torres_strait_islander_first_action_plan.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 38. National Mental Health Commission. The National Children's Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024‐03/national‐children‐s‐mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐strategy‐‐‐full‐report.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 39. Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care. National Preventive Health Strategy 2021–2030. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/12/national‐preventive‐health‐strategy‐2021‐2030_1.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 40. Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care. National Action Plan for the Health of Children and Young People 2020–2030. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/04/national‐action‐plan‐for‐the‐health‐of‐children‐and‐young‐people‐2020‐2030‐national‐action‐plan‐for‐the‐health‐of‐children‐and‐young‐people‐2020‐2030.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 41. Australian Government, Department of Social Services. Entrenched disadvantage package. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2023/entrenched_disadvantage_package_budget_fact_sheet_fa.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 42. Calder R, Dakin P. Valued, loved and safe: the foundations for healthy individuals and a healthier society. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S11‐S14. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/valued‐loved‐and‐safe‐foundations‐healthy‐individuals‐and‐healthier‐society

- 43. Moore T, Arefadib N, Deery A, et al. The first thousand days: an evidence paper. Melbourne: Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children's Research Institute; 2017. https://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccchdev/CCCH‐The‐First‐Thousand‐Days‐An‐Evidence‐Paper‐September‐2017.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 44. Grummitt L, Baldwin JR, Lafoa'i J, et al. Burden of Mental Disorders and Suicide Attributable to Childhood Maltreatment. JAMA Psychiatry 2024; 81: 782‐788.

- 45. Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, et al. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non‐randomised, interventional trial. Lancet Glob Health 2021; 9: e651‐e659.

- 46. Centre for Policy Development. Starting better: a guarantee for young children and families. Sydney: CPD, 2021. https://cpd.org.au/work/starting‐better‐centre‐for‐policy‐development/ (viewed July 2024).

- 47. Goldfeld S, Bryson H, Mensah F, et al. Nurse home visiting to improve child and maternal outcomes: 5‐year follow‐up of an Australian randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2022; 17: e0277773.

- 48. Harman‐Smith Y, Gregory T, Monroy NS, Perfect D. National trends in child development — AEDC 2021 data story. Canberra: Australian Early Development Census, Australian Government; 2023. https://www.aedc.gov.au/resources/detail/national‐trends‐in‐child‐development—aedc‐2021‐data‐story (viewed May 2024).

- 49. Australian Government, Productivity Commission. Closing the Gap — information repository [website]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2024. https://www.pc.gov.au/closing‐the‐gap‐data/dashboard (viewed Aug 2024).

- 50. Health Ministers’ Meeting. National Obesity Strategy 2022–2032. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐obesity‐strategy‐2022‐2032?language=en (viewed July 2024).

- 51. Lycett K, Frykberg G, Azzopardi PS, et al. Monitoring the physical and mental health of Australian children and young people: a foundation for responsive and accountable actions. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S20‐S24. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/monitoring‐physical‐and‐mental‐health‐australian‐children‐and‐young‐people

- 52. Lawrence D, Johnson SE, Hafekost J, et al. The mental health of children and adolescents: report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care, Commonwealth of Australia; 2015. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/the‐mental‐health‐of‐children‐and‐adolescents (viewed June 2024).

- 53. Patton GC, Olsson CA, Skirbekk V, et al. Adolescence and the next generation. Nature 2018; 554: 458‐466.

- 54. Pitt H, McCarthy S, Arnot G. Children, young people and the commercial determinants of health. Health Promot Int 2024; 39: daad185.

- 55. Moodie R, Bennett E, Kwong EJL, et al. Ultra‐processed profits: the political economy of countering the global spread of ultra‐processed foods — a synthesis review on the market and political practices of transnational food corporations and strategic public health responses. Int J Health Policy Manag 2021; 10: 968‐982.

- 56. Hudders L, De Pauw P, Cauberghe V, et al. Shedding new light on how advertising literacy can affect children's processing of embedded advertising formats: a future research agenda. J Advert 2017; 46: 333‐349.

- 57. Coates A, Boyland E. Kid influencers — a new arena of social media food marketing. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2021; 17: 133‐134.

- 58. Backholer K, Boyland E, Sing F. Chapter 2: commercial determinants of noncommunicable diseases in the WHO European region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2024. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289061162 (viewed Sept 2024).

- 59. Clark H, Coll‐Seck AM, Banerjee A, et al. A future for the world's children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020; 395: 605‐658.

- 60. Backholer K, Gupta A, Zorbas C, et al. Differential exposure to, and potential impact of, unhealthy advertising to children by socio‐economic and ethnic groups: a systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev 2021; 22: e13144.

- 61. Crocetti AC, Cubillo Larrakia B, Lock Ngiyampaa M, et al. The commercial determinants of Indigenous health and well‐being: a systematic scoping review. BMJ Glob Health 2022; 7: e010366.

- 62. Al‐Jawaldeh A, Jabbour J. Marketing of food and beverages to children in the Eastern Mediterranean region: a situational analysis of the regulatory framework. Front Nutr 2022; 9: 868937.

- 63. Attorney‐General's Department. Privacy Act Review Report 2022. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. https://www.ag.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐02/privacy‐act‐review‐report_0.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 64. Carroll L, Thompson A. New school targets, funding boost needed to overhaul “entrenched” disadvantage: report. The Age 2023; 11 Dec. https://www.theage.com.au/politics/federal/new‐school‐targets‐funding‐boost‐needed‐to‐overhaul‐entrenched‐disadvantage‐report‐20231211‐p5eqm8.html (viewed June 2024).

- 65. Welsh J, Bishop K, Booth H, et al. Inequalities in life expectancy in Australia according to education level: a whole‐of‐population record linkage study. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20: 178.

- 66. Hamilton C, Hamilton M. The privileged few. John Wiley and Sons, 2024.

- 67. Australian Government, Department of Education. Improving Outcomes for All: Australian Government summary report of the Review to Inform a Better and Fairer Education System. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.education.gov.au/review‐inform‐better‐and‐fairer‐education‐system/review‐inform‐better‐and‐fairer‐education‐system‐reports (viewed July 2024).

- 68. Australian Government, Productivity Commission. Review of the National School Reform Agreement, Study Report. 2022. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/school‐agreement/report/school‐agreement.pdf (viewed Sept 2024).

- 69. Sahlberg P, Goldfeld SR. New foundations for learning in Australia. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S25‐S29. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/new‐foundations‐learning‐australia

- 70. Australian Government, Department of Education. Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. Melbourne: Education Services Australia, 2019. https://www.education.gov.au/alice‐springs‐mparntwe‐education‐declaration/resources/alice‐springs‐mparntwe‐education‐declaration (viewed July 2024).

- 71. Groch S, Koehn E. The accounting tricks shortchanging public schools billions of dollars every year. The Sydney Morning Herald 2024; 27 Jan. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/the‐accounting‐tricks‐shortchanging‐public‐schools‐billions‐of‐dollars‐every‐year‐20240116‐p5exn1.html (viewed June 2024).

- 72. Clare J, Cook R, Buti T; Ministers’ Media Centre. Australian and WA Governments agree to fully and fairly fund all Western Australian public schools [media release]. 31 Jan 2024. https://ministers.education.gov.au/clare/australian‐and‐wa‐governments‐agree‐fully‐and‐fairly‐fund‐all‐western‐australian‐public (viewed June 2024).

- 73. Kapeke K, Muse K, Rowan J, et al. Who holds power in decision making for young people's future? Med J Aust 2023; 219: S30‐S34. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/who‐holds‐power‐decision‐making‐young‐peoples‐future#:~:text=Children%20and%20young%20people%20have,decisions%20that%20affect%20their%20futures

- 74. Masson‐Delmotte V, Zhaj P, Pirani SL, et al. Summary for Policymakers. In: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge (UK) and New York (NY, USA): Cambridge University Press, 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_SPM.pdf (viewed Oct 2024).

- 75. Davidson P, Bradbury B. The wealth inequality pandemic: COVID and wealth inequality. Sydney: ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership, 2022. https://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2022/07/The‐wealth‐inequality‐pandemic_COVID‐and‐wealth‐inequality_screen.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 76. Bessell S and Vuckovic C. How child inclusive were Australia's responses to COVID‐19? Aust J Soc Issues 2022; https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.232 [Epub ahead of print].

- 77. Ganguly A, Morelli D, Bhavan KP. Voting as a social determinant of health: leveraging health systems to increase access to voting. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv 2023; 4.

- 78. Bessant J, Bessell S, Black R, et al. Submission to the Inquiry into the Electoral Amendment Bill 2021 by the Standing Committee on Justice and Community Safety Committee in the Legislative Assembly. Canberra: Legislative Assembly for the Australian Capital Territory, 2022. https://www.parliament.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1942777/Submission‐06‐Professor‐Judith‐Bessant‐and‐29‐others.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 79. Australian Electoral Commission. National youth enrolment rate. Canberra: AEC, 2024. https://www.aec.gov.au/Enrolling_to_vote/Enrolment_stats/performance/national‐youth.htm (viewed Aug 2024).

- 80. McHale R, Brennan N, Freeburn T, Rossetto A. Youth Survey Report 2023. Mission Australia, 2023. https://www.missionaustralia.com.au/publications/youth‐survey (viewed July 2024).

- 81. Bessant J. Mixed messages: Youth participation and democratic practice. Aust J Polit Sci 2004; 39: 387‐404.

- 82. Australia Institute. Compulsory voting: ensuring government of the people, by the people, for the people. Canberra: Australia Institute, 2019. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2020/12/P691‐Compulsory‐voting‐briefing‐note‐WEB.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 83. Richardson TE, Yanada BA, Watters D, et al. What young Australians think about a tax on sugar‐sweetened beverages. Aust N Z J Public Health 2019; 43: 63‐67.

- 84. Make It 16 Australia. Young people launch national campaign to lower the voting age [media release]. 12 June 2023. https://www.makeit16.au/make‐it‐16/posts/young‐people‐launch‐national‐campaign‐to‐lower‐the‐voting‐age (viewed June 2024).

- 85. Secretariat of National Aboriginal and Islander Child Care. Funding Model Options for ACCO Integrated Early Years Services — final report. Canberra: SNAICC, 2024. https://www.snaicc.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2024/05/240507‐ACCO‐Funding‐Report.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 86. Perry J, Egginton E, Alfrey K. Thriving Kids in Disasters. Brisbane: Thriving Queensland Kids Partnership, Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth; 2024. https://www.aracy.org.au/the‐nest‐in‐action/resources/thriving‐kids‐in‐disasters (viewed June 2024).

- 87. Tollefson J. Top climate scientists are sceptical that nations will rein in global warming. Nature 2021; 599: 22‐24.

- 88. CSIRO. Australia's changing climate [website]. Canberra: CSIRO, 2022. https://www.csiro.au/en/research/environmental‐impacts/climate‐change/State‐of‐the‐Climate/Australias‐Changing‐Climate (viewed June 2024).

- 89. Nishant N, Ji F, Guo Y, et al. Future population exposure to Australian heatwaves. Environmental Research Letters 2022; 17: 064030.

- 90. Climate Action Tracker. Australia: country summary [website]. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/australia (viewed May 2024).

- 91. Timar E, Gromada A, Rees G, Carraro A. Places and spaces: environments and children's well‐being. Innocenti Report Card 17. Florence: UNICEF Innocenti — Office of Research, 2022. https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/reports/places‐and‐spaces‐environments‐and‐childrens‐well‐being#download (viewed Aug 2024).

- 92. Morison E. Climate of the Nation 2023: tracking Australia's attitudes towards climate change and energy. Canberra: Australia Institute, 2023. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/09/Climate‐of‐the‐Nation‐2023‐Web.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 93. Ritchie H, Rosado P, Roser M. Data page: year‐on‐year change in CO₂ emissions. Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/absolute‐change‐co2?tab=chart®ion=Oceania&country=~AUS (viewed Aug 2024).

- 94. International Energy Agency. Net zero by 2050: a roadmap for the global energy sector. Paris: IEA, 2021. https://www.iea.org/reports/net‐zero‐by‐2050 (viewed June 2024).

- 95. United Nations Environment Programme. Governments’ fossil fuel production plans dangerously out of sync with Paris limits. UN, 2021. https://www.unep.org/news‐and‐stories/press‐release/governments‐fossil‐fuel‐production‐plans‐dangerously‐out‐sync‐paris (viewed June 2024).

- 96. Australia Institute. An open letter from Australian scientists and experts — no new fossil fuel projects. Canberra: Australia Institute, 2023. https://nb.australiainstitute.org.au/scientists_open_letter (viewed June 2024).

- 97. Welsby D, Price J, Pye S, Ekins P. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5°C world. Nature 2021; 597: 230‐234.

- 98. Australian Government, Department of Industry Science and Resources. Resources and energy major projects 2023 report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐12/resources‐and‐energy‐major‐projects‐2023.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 99. Ritchie H, Rosado P, Roser M. Data Page: Share of electricity generated by renewables. Our World in Data, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/share‐of‐electricity‐production‐from‐renewable‐sources?country=~AUS (viewed Aug 2024).

- 100. Campbell R, Ogge M, Verstegan P. New fossil fuel projects in Australia 2023. Canberra: Australia Institute, 2023. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/03/P1359‐New‐fossil‐fuel‐projects‐on‐major‐projects‐list‐and‐emissions‐WEB.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 101. United Nations. REV2 Declaration on Future Generations. New York: UN, 2024. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sotf‐declaration‐on‐future‐generations‐rev2.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 102. Common Sense Policy Group; Pickett K, Wilkinson R, Dorling D. Act now: a vision for a better future and a new social contract. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2024.

- 103. Sindall C, Lo S, Capon T. Governance for the well‐being of future generations. J Paediatr Child Health 2021; 57: 1749‐1753.

- 104. Rimmer SH, Stephenson E, Hawkins T. A fair go for all: intergenerational justice policy survey. EveryGen, 2024. https://giwl.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/A%20Fair%20Go%20for%20All%20Report.pdf (viewed June 2024).

- 105. Foundations for Tomorrow. Shaping the Australia of the future. https://www.foundationsfortomorrow.org/ (viewed Aug 2024).

- 106. Foundations for Tomorrow. The Australian Parliamentary Group for Future Generations. https://www.foundationsfortomorrow.org/australian‐parliamentary‐group‐for‐future‐generations (viewed Aug 2024).

- 107. EveryGen, Foundation for Young Australians, Foundations for Tomorrow, et al. The Intergenerational Fairness Coalition. https://www.foundationsfortomorrow.org/intergenerational‐fairness‐coalition (viewed Aug 2024).

- 108. Howe S, Nutbeam D. Interview with inaugural Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, Sophie Howe: embedding a wellbeing approach in government. Public Health Res Pract 2023; 33: 3322314.

- 109. Welsh Government. Well‐being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/anaw/2015/2/contents (viewed July 2024).

- 110. Davies H. The well‐being of future generations (Wales) Act 2015 — a step change in the legal protection of the interests of future generations? Journal of Environmental Law 2017; 29: 165‐175.

Abstract

Introduction: This consensus statement recommends eight high‐level trackable policy actions most likely to significantly improve health and wellbeing for children and young people by 2030. These policy actions include an overarching policy action and span seven interconnected domains that need to be adequately resourced for every young person to thrive: Material basics; Valued, loved and safe; Positive sense of identity and culture; Learning and employment pathways; Healthy; Participating; and Environments and sustainable futures.

Main recommendations:

Changes in approach as a result of this statement: Together, these achievable evidence‐based policies would significantly improve children and young people's health and wellbeing by 2030, build a strong foundation for future generations, and provide co‐benefits for all generations and society.