There is increasing interest internationally in the potential for integrated care hubs to improve mental health outcomes for children experiencing adversity.1 Termed “child and family hubs” throughout this article, these hubs refer to collaborative initiatives integrating health, education and/or social care, typically in one site. In Australia, the 2020 Productivity Commission Mental Health Inquiry identified the need for significant reform, including focus on early intervention and person‐centred care in childhood and adolescence, to address the shortcomings of siloed national mental health care systems and to increase accessibility of care for families at greatest risk of experiencing adversity.2 Childhood adversity is a broad term used to describe negative early life experiences and circumstances, such as socio‐economic disadvantage, abuse, neglect, family violence, parental mental illness, bullying and discrimination.3,4 The cumulative and negative impacts of childhood adversity on intergenerational health and wellbeing are significant, and necessitate a multisectoral response.5 This article is part of the 2024 MJA supplement for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030,6 which examines how participating affects the health and wellbeing of children, young people and future generations. We look at this from the perspective of a public community paediatric service in metropolitan Sydney, involved in co‐designing child and family hubs to deliver health services to families experiencing adversity.

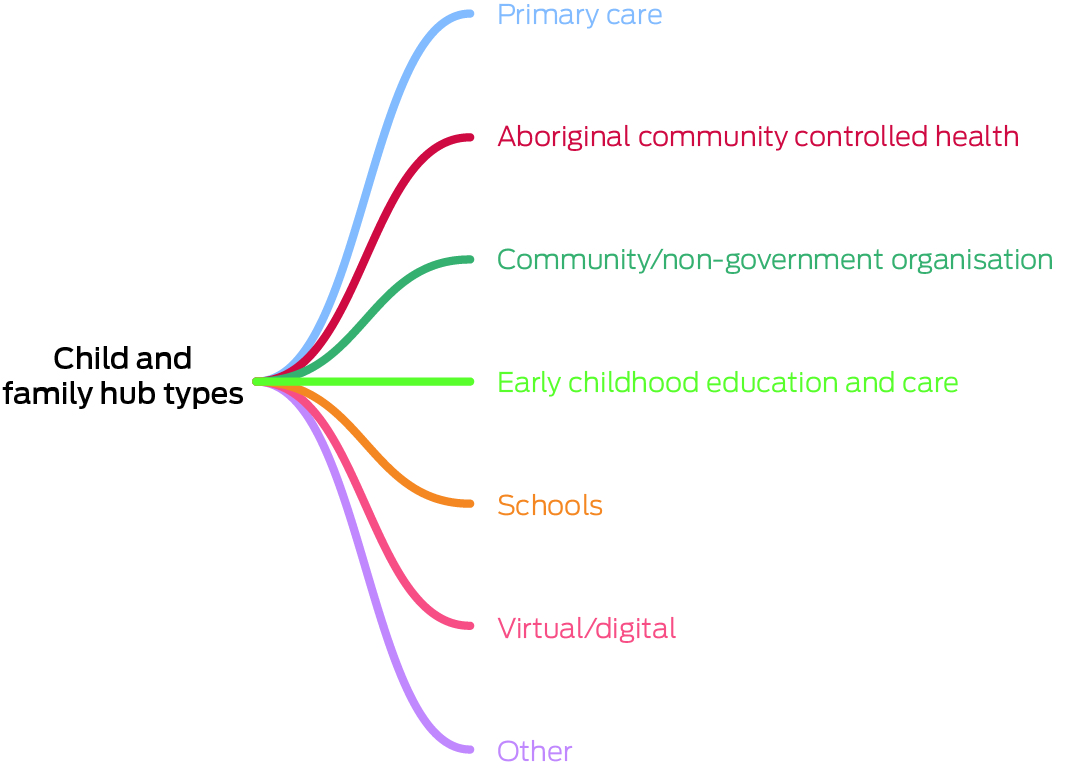

There are currently over 460 Australian child and family hubs that focus on building connections between existing services to create a “one‐stop shop” for families seeking support in relation to health, development and wellbeing.7,8 Although organisational adaptation varies by context (Box 1), several core components of child and family hubs can be identified. These include co‐design of hub components with families, non‐stigmatising entry, family‐centred care, parental capacity building, co‐location of services, workforce development, and local leadership.9

To best respond to the needs of local communities, a robust co‐design of child and family hubs should involve people with lived and professional experience of health and social care service utilisation and provision. Co‐design is a method on the continuum of participatory approaches to service development and evaluation, which are essential for preventing services that fail to engage vulnerable families by not meeting their needs, or by failing to optimise cultural safety.10 We define co‐design as the “active involvement of a diverse range of participants in exploring, developing, and testing responses to shared challenges”.11 Given the increase in utilisation of co‐design in research, clear reporting of the methods, process and tools of co‐design is crucial for advancing the health service and system knowledge base.12 To this end, we describe the experience of a metropolitan public community paediatric service in Sydney Local Health District (SLHD) in collaborative co‐designing child and family hubs across health, education and digital initiatives. Each case study provides practical detail regarding the involvement of children and families in service design and challenges encountered, to inform learnings for future developers of integrated child and family hubs.

Health service hubs: Wyndham Vale and Marrickville

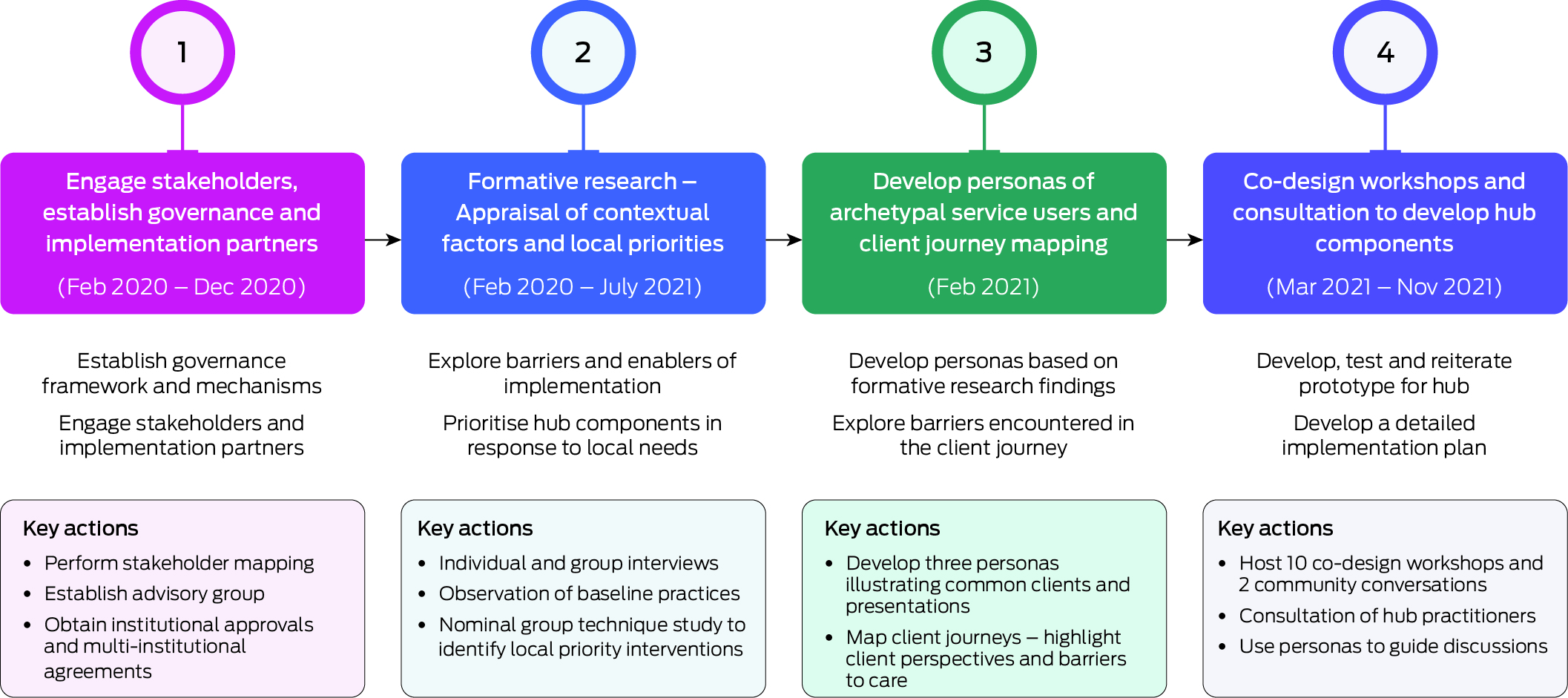

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health oversaw the co‐design of two child and family hubs, seeking to improve the mental health of children (aged zero to eight years) by earlier detection and response to family adversity.13 One hub was developed in Wyndham Vale in Victoria, and a second in the SLHD Marrickville Community Health Centre in New South Wales. The Wyndham Vale Child and Family Hub was co‐designed using mixed methods across four stages, between February 2020 and November 2021 (Box 2). Stages 1 and 2 of this process were replicated in Marrickville between August and November 2021. Researchers involved in the co‐design process did not have concurrent clinical responsibilities within the hub sites. Learnings were shared across sites to develop the child and family hubs in an iterative manner, responding to the needs and preferences of service users and providers.10

Co‐design methods

The co‐design process in Wyndham Vale involved local families and intersectoral service providers from a range of professional backgrounds across health, legal, council, education and non‐government organisation sectors (121 family participants and 80 practitioners in Wyndham Vale). Stage 1 involved stakeholder mapping and formation of implementation and evaluation partnership. Stage 2 involved individual semi‐structured interviewing, focus groups, observation of clinical encounters, and an online nominal group technique consensus study,14 which enabled stakeholders to collaboratively rate, prioritise and discuss ideas in a focus group setting.15 Stage 3 involved the development of personas based on formative research findings — fictional characters created to represent an archetypal family's journey through a service.16 Stage 4 involved seven full‐day co‐design workshops focusing on the client journey through the hub, two community conversation sessions, and workforce consultations. In Marrickville, the co‐design approach involved individual semi‐structured interviews (ten parents/primary caregivers and 16 service providers), and 11 nominal group technique workshops involving 14 parents/primary caregivers and 20 service providers from health, legal, council, education and non‐government organisation sectors.

Engaging children in co‐design

In Wyndham Vale, two community conversation sessions were held in a local shopping centre and community centre. To engage children and young people in the co‐design process, a participatory art‐based activity provided a means of capturing their preferences and perspectives on how to shape the Wyndham Vale hub into a welcoming environment. Time and resource limitations precluded replication of community conversation sessions in the Marrickville site.

Co‐designed components of the child and family hubs

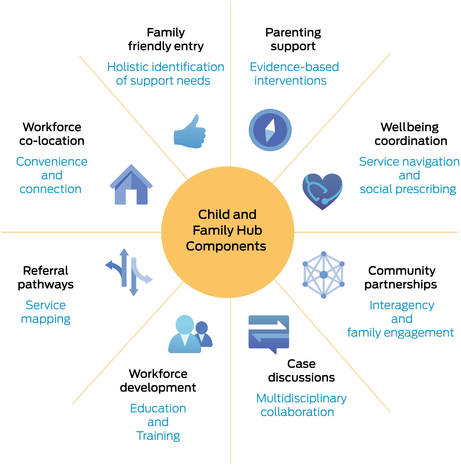

The co‐designed components of the Child and Family Hub at Wyndham Vale are detailed in Box 3. The priority components of the Marrickville Child and Family Hub were very similar, with two exceptions. Multidisciplinary case discussions and access to parenting supports were embedded in the Marrickville Community Health Centre at baseline. Therefore, these components were not highlighted as priorities for the hub developed in that site. Rather, service mapping and care navigation were prioritised, alongside enhanced participation of health representatives at the existing council‐led Inner West Children and Families Interagency.17

Health justice partnerships (involving co‐location of lawyers providing legal consultations within the health centre) were introduced at both sites. At both sites, a Wellbeing Coordinator (named “service navigator” in Marrickville) was employed to link families with appropriate sources of health and social care, based on jointly identified priorities using a social prescription framework.3

Ongoing evaluation of both Child and Family Hubs is seeking to understand which hub components work best, for whom, and under what circumstances.13

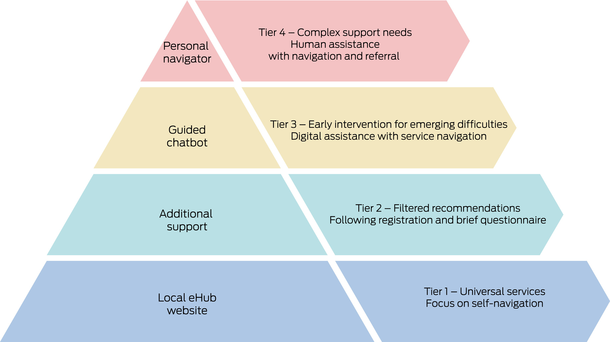

The child and family eHub

Digital innovations can provide high reach, low stigma solutions for increasing accessibility to services and supports found within physical child and family hubs. In 2021, funding was obtained via a NHMRC Partnership Grant to co‐design and evaluate a digital platform for supporting the mental health needs of families of children (aged zero to twelve years), with particular emphasis on families experiencing adversity. A child and family eHub is now under development, which aims to improve mental health outcomes for children and families experiencing adversity by facilitating access to the right services and caregiver information, at the right time. Through a proportionate universalism approach,18 the eHub will seek to deliver universal services at the scale and intensity needed by the end user (Box 4). Many collaborators involved in this initiative were involved in the implementation and evaluation of the child and family hubs in Wyndham Vale and Marrickville. These sites, along with a third site in Fairfield, NSW, have been selected as test sites for the eHub.

User‐centred design methods

To develop the eHub, user‐centred design was used to understand the needs and behaviours of caregivers when seeking information and access to services for their child's mental health concerns.19 The terminology “user‐centred design” (as distinct from co‐design) was used to describe the incorporation of the views and experiences of end users in the design process, without their active participation in service design.11 Engaging caregivers of children aged zero to twelve years experiencing adversity in the three pilot sites, as well as researchers and experts in digital health intervention, the iterative user‐centred design process involved:

- assumption mapping and mapping of existing technology to identify opportunities;

- in‐depth individual caregiver interviews (n = 13) to understand information and service‐seeking behaviours and needs;

- creation of caregiver personas informed by individual interviews, story maps of specific product features and functionality, and a journey map of the user experience;

- a workshop with digital experts to define high level eHub design features, in alignment with caregiver needs; and

- development of a minimum viable product and prototype testing alongside caregivers (n = 6), to refine specifications based on their inputs regarding acceptability and usability.

Evaluation of the minimum viable product is underway, to assess the extent to which the eHub supports caregivers to find services, information, online programs and parent groups to support their family. Secondary outcomes will consider whether the eHub increases families’ use of information and services, and whether it improves mental health outcomes.

A school‐based hub: Ngaramadhi Space

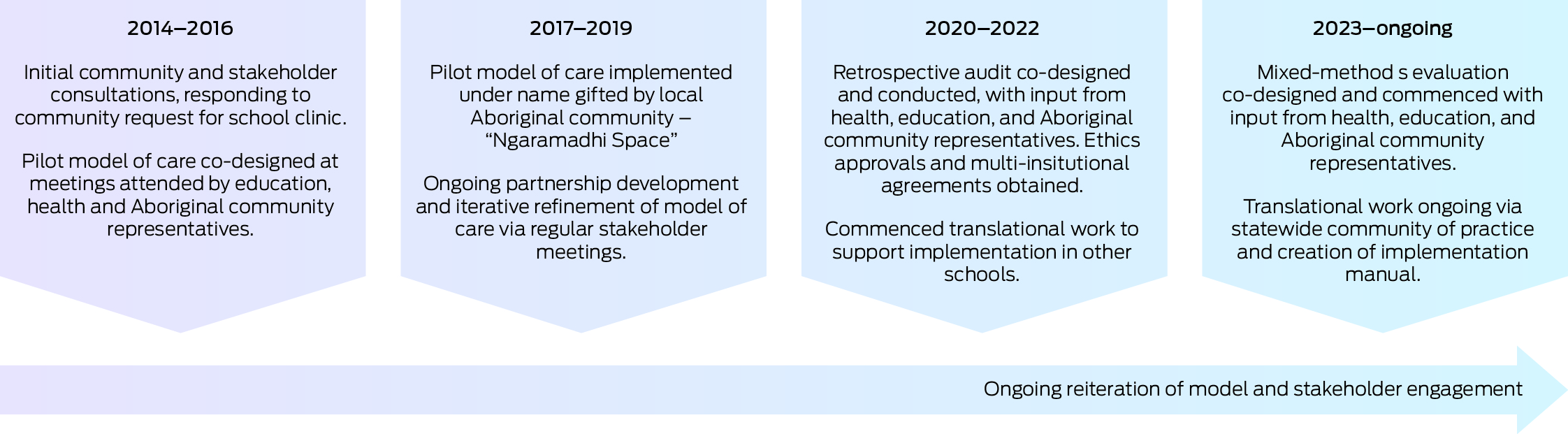

School‐based hubs have an expanding evidence base globally and act as familiar and convenient locations for children and families to access health services.20,21,22,23 In the SLHD, a pilot school‐based integrated care program was established in response to community members voicing a desire for access to health services via integrated “one‐stop shops” located in schools.24 This idea arose through a broad community consultation process embedded within the SLHD Healthy Homes and Neighbourhoods interagency care coordination initiative.25 Yudi Gunyi School was identified as an ideal location, due to the high needs of its students. Yudi Gunyi School is a specialised secondary school for students experiencing challenging behaviours that preclude them from attending mainstream schooling. In this school, the Ngaramadhi Space model of care was co‐designed with the Aboriginal community over a decade, to provide holistic, multidisciplinary and child and family‐centred care (Box 5).26

Co‐design methods

Co‐design in the setting of Yudi Gunyi School was challenging but important. Stakeholders from health, education, the social care sector and the Aboriginal community set a shared goal of addressing the holistic needs of students and families. This included the physical health, mental health, learning, psychological and social issues experienced by students.26 Students and families experienced marginalisation because of the nature of their externalising behaviours and psychosocial vulnerabilities. This made active engagement with students and families for the purposes of co‐design difficult. A continuous, long term approach to co‐design was established with Aboriginal community representatives. As students were assessed over time, regular case review meetings (attended by Ngaramadhi Space service providers) were a forum for discussing processes. Student feedback was obtained after attending Ngaramadhi Space using a five item Likert survey. Refinement of the model occurred via regular stakeholder meetings with Aboriginal community representatives, who gifted the program the name “Ngaramadhi” which means “deep listening” in Dharawal language.27

Co‐design outcomes

Aboriginal community representatives emphasised the need for an open plan layout and for artwork that was welcoming for Aboriginal families. The co‐developed model of care involves a team comprising a paediatrician, youth health nurse, social worker, school counsellor, speech therapist and occupational therapist, with consultation provided by a child and adolescent psychiatrist. The team collates information about the child and then proceeds to a fluid and child‐centred assessment, focusing on holistic formulation of the needs of the student, and active follow‐up of recommendations.

Over time, the Ngaramadhi Space model was integrated within Yudi Gunyi School, with processes undertaken to formalise the role of the program within the school. This included the Wouwanguul Kanja community reference group, forming a memorandum of understanding with the SLHD, initiating professional development and supervision pathways, and partnering on a formal evaluation.26 This mixed methods evaluation of Ngaramadhi Space demonstrated alignment with the World Health Organization Integrated Person‐Centred Health Service framework,28 through its community‐driven approach and its focus on culturally safety, multidisciplinary collaboration and equitable access to care. Qualitative evaluation demonstrated the model was highly acceptable to families and the community.9 Quantitative analysis of data collected before and after engagement with Ngaramadhi Space showed improved access to health care for students and significant improvements in teacher‐reported behavioural scores.29

The Ngaramadhi Space model of care has since been replicated in nine schools within the SLHD under the name “Kalgal Burnbona”, meaning “to surround family” in the Dharawal language.30 Other integrated care models in school settings have independently emerged across Australia.31 Ongoing translational research is seeking to inform the scale up of school‐based integrated care across Australia, and the team are providing leadership and support to other programs via a NSW community of practice, formed alongside the national Australasian School‐Based Health Alliance.

Learnings from the co‐design process

There is an increasing expectation that health and social services will be co‐designed with end users. The collective experience of co‐designing child and family hubs across three contexts (health, education and digital settings), as described in this article, has highlighted several key learnings. Across all hubs described, families of children experiencing adversity expressed a need for assistance with service navigation and whole‐of‐family support. Although implementation of these principles varied across hubs, stakeholders with lived experience of adversity expressed the importance of their involvement in the service design and implementation process.

The cases described in this article demonstrate that co‐design involving families experiencing adversity is possible but challenging. Co‐design of the child and family hubs in Wyndham Vale and Marrickville followed a staged approach within a well defined theoretical framework.10 This approach required substantial investment in terms of both funding and time, and was achieved with employment of dedicated research personnel. Formal evaluations of the child and family hubs are ongoing, but the value of the robust approach to the co‐design process employed in Wyndham Vale was assessed specifically, using the Public and Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool (PPEET).32 Co‐design participants of varying backgrounds were found to derive satisfaction from the process of working collaboratively to generate mutual learning, and the process was seen to increase local trust in, and ownership of, the hub.10

The importance of trust and community ownership was reiterated in the co‐design of the Ngaramadhi Space school‐based hub, where a pragmatic approach to co‐design was required. The community‐driven nature of the program meant that action (ie, the urgent assessment of students with high needs) took precedence over formal co‐design within a research framework. By listening to the community and taking a stepwise approach to implementation, we sought to gain the trust of the community, students and families. As trust increased, measures to involve families in model refinement were developed; for example, consumer satisfaction surveys and a formal research qualitative evaluation with ethics approvals.9

The process of building trust and deeply rooted connections with the community took years and is ongoing, as both community stakeholders and providers changed over time.

For services catering to families experiencing adversity, the challenge of engaging parents and caregivers in co‐design is compounded by a range psychosocial complexity. The health‐based hubs and eHub described here illustrate that it is achievable, and the Ngaramadhi Space experience demonstrates the importance of community representatives, where very significant care needs hinder direct engagement of caregivers in co‐design.

Children and young people can contribute directly to co‐design of services for families experiencing adversity, as demonstrated in the development of the Wyndham Vale Child and Family Hub. However, the power discrepancy between children and adults is amplified in this context, and a reflexive approach is essential. Consideration of developmentally age‐appropriate communication and child‐friendly settings are essential. As illustrated in the Wyndham Vale hub, creative approaches involving participatory art‐based activities can be useful.

Conclusion

For services catering to younger children and families experiencing adversity, collaboration with parents and carers is key. Self‐advocacy becomes increasingly important for children and adolescents over time, and engaging children and young people in co‐design processes is essential but challenging. Further research is needed to explore how the voices and perspectives of younger children can be meaningfully embedded into service development in Australia, particularly for services catering for families with complex needs. Participatory approaches to health service design, involving genuine partnerships with children, young people and families, are feasible with sufficient investment in resource and workforce skills. However, further research is needed to inform which approaches are most robust and authentic for specific circumstances, and which result in higher quality service design and outcomes.

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Honisett S, Loftus H, Hall T, et al. Do integrated hub models of care improve mental health outcomes for children experiencing adversity? A systematic review. Int J Integr Care 2022; 22: 24.

- 2. Productivity Commission. Mental Health Inquiry report [report No. 95]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental‐health/report (viewed Aug 2024).

- 3. Hall T, Constable L, Loveday S, et al. Identifying and responding to family adversity in Australian community and primary health settings: a multi‐site cross sectional study. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1147721.

- 4. Karatekin C, Hill M. Expanding the original definition of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). J Child Adolesc Trauma 2019; 12: 289‐306.

- 5. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017; 2: e356‐e366.

- 6. Lycett K, Cleary J, Calder R, et al. A framework for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030: tracking the health and wellbeing of children and young people to hold Australia to account. Med J Aust 2023; 219: S3‐S10. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/10/framework‐future‐healthy‐countdown‐2030‐tracking‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐children

- 7. National Child and Family Hubs Network. Integrated Child and Family Hubs — a plan for Australia. https://www.pc.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/377224/sub220‐childhood‐attachment2.pdf Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. (viewed Aug 2024).

- 8. Deloitte Access Economics. Exploring need and funding models for a national approach to integrated child and family centres. Commissioned by Social Ventures Australia in partnership with the Centre for Community Child Health [May 2023]. https://www.deloitte.com/au/en/services/economics/perspectives/exploring‐need‐funding‐models‐national‐approach‐integrated‐child‐family‐centres.html (viewed Aug 2024).

- 9. Honisett S, Cahill R, Callard N, et al. Child and family hubs: an important “front door” for equitable support for families across Australia. Melbourne: National Child and Family Hubs Network, Murdoch Children's Research Institute; 2023. https://doi.org/10.25374/MCRI.22031951 (viewed Oct 2024).

- 10. Hall T, Loveday S, Pullen S, et al. Co‐designing an integrated health and social care hub with and for families experiencing adversity. Int J Integr Care 2023; 23: 3.

- 11. Blomkamp E. The promise of co‐design for public policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration 2018; 77: 729‐743.

- 12. Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co‐design in health: a rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst 2020; 18: 17.

- 13. Hall T, Goldfeld S, Loftus H, et al. Integrated Child and Family Hub models for detecting and responding to family adversity: protocol for a mixed‐methods evaluation in two sites. BMJ Open 2022; 12: e055431.

- 14. Hall T, Honisett S, Paton K, et al. Prioritising interventions for preventing mental health problems for children experiencing adversity: a modified nominal group technique Australian consensus study. BMC Psychol 2021; 9: 165.

- 15. Cantrill JA, Sibbald B, Buetow S. The Delphi and nominal group techniques in health services research. Int J Pharm Pract 2011; 4: 67‐74.

- 16. Pruitt J, Grudin J. Personas: practice and theory. Proceedings of the 2003 conference on Designing for user experiences. San Francisco (USA): Association for Computing Machinery; 6–7 June 2003; pp 1‐15. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/997078.997089 (viewed Oct 2024).

- 17. Inner West Council. Inner West Children and Families Interagency guidelines. Sydney: Inner West Council, 2024. https://www.innerwest.nsw.gov.au/live/community‐well‐being/children‐and‐families/inner‐west‐children‐and‐families‐interagency (viewed Aug 2024).

- 18. Carey G, Crammond B, De Leeuw E. Towards health equity: a framework for the application of proportionate universalism. Int J Equity Health 2015; 14: 81.

- 19. Honisett S, Williams I, Woolfenden S, et al. Developing a digital eHub to improve caregiver access to and use of existing primary health, mental health, and social services. Third Asia Pacific Conference on Integrated Care (APIC3), International Foundation for Integrated Care; Sydney (Australia), 13–15 Nov 2023. https://integratedcarefoundation.org/events/apic3‐3rd‐asia‐pacific‐conference‐on‐integrated‐care‐sydney‐australia (viewed Oct 2024).

- 20. Arenson M, Hudson PJ, Lee N, et al. The evidence on school‐based health centers: a review. Glob Pediatr Health 2019; 6: 2333794x19828745.

- 21. Allensworth DD, Kolbe LJ. The comprehensive school health program: exploring an expanded concept. J Sch Health 1987; 57: 409‐412.

- 22. Kolbe LJ, Allensworth DD, Potts‐Datema W, et al. What have we learned from collaborative partnerships to concomitantly improve both education and health? J Sch Health 2015; 85: 766‐774.

- 23. World Health Organization. Making every school a health‐promoting school — implementation guidance. WHO, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025073 (viewed Aug 2024).

- 24. Rungan S, Smith‐Merry J, Liu HM, et al. School‐based integrated care within Sydney Local Health District: a qualitative study about partnerships between the education and health sectors. Int J Integr Care 2024; 24: 13.

- 25. Eastwood JG, Shaw M, Garg P, et al. Designing an integrated care initiative for vulnerable families: operationalisation of realist causal and programme theory, Sydney Australia. Int J Integr Care 2019; 19: 10.

- 26. Rungan S, Gardner S, Liu HM, et al. Ngaramadhi Space: an integrated, multisector model of care for students experiencing problematic externalising behaviour. Int J Integr Care 2023; 23: 19.

- 27. Gonski Institute for Education. Yudi Gunyi School Ngaramadhi Space Wraparound Program research report. Sydbey: UNSW Sydney, 2020. https://yudigunyi‐s.schools.nsw.gov.au/content/dam/doe/sws/schools/y/yudigunyi‐s/news/Yudi‐Gunyi‐School‐Final‐Report.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 28. World Health Organization. Framework on integrated, people‐centred health services [A69/39]. WHO, 2016. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39‐en.pdf (viewed Aug 2024).

- 29. Rungan S, Montgomery A, Smith‐Merry J, et al. Retrospective audit of a school‐based integrated health‐care model in a specialised school for children with externalising behaviour. J Paediatr Child Health 2023; 59: 1311‐1318.

- 30. Rungan S, Liu HM, Smith‐Merry J, et al. Kalgal Burnbona: an integrated model of care between the health and education sector. Int J Integr Care 2024; 24: 14.

- 31. Mendoza Diaz A, Leslie A, Burman C, et al. School‐based integrated healthcare model: how Our Mia Mia is improving health and education outcomes for children and young people. Aust J Prim Health 2021; 27: 71‐75.

- 32. Moore A, Wu Y, Kwakkenbos L, et al. The Patient Engagement Evaluation Tool was valid for clinical practice guideline development. J Clin Epidemiol 2022; 143: 61‐72.

This article is part of the 2024 MJA supplement on the Future Healthy Countdown 2030, which was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) — a pioneer in health promotion that was established by the Parliament of Victoria as part of the Tobacco Act 1987, and an organisation that is primarily focused on promoting good health and preventing chronic disease for all. We also acknowledge the Sydney Local Health District for their support of this article, in addition to the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre for Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health, the Ngaramadhi Space and Kalgal Burnbona teams, and the Child and Family eHub. The funders had no role in the planning, writing or publication of the work.

The Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health is co‐funded by the NHMRC and Beyond Blue (Harriet Hiscock is the principal investigator). The Child and Family eHub is funded by an NHMRC Partnership Projects grant (Sharon Goldfeld is the principal investigator). The Ngaramadhi Space has no external grant funding.