Over the past decade, inequities in children's health, development and wellbeing have not improved despite great efforts globally.1 Inequities are unfair and unjust differences caused by preventable social, economic or geographic factors. Inequities generally persist into adulthood, where they carry high costs for individuals and society,2 generating substantial costs across health, education and welfare budgets.3 This is an extraordinary system failure for any high income country, including Australia.3 Addressing inequities would generate substantial savings across budgets and raise the productivity of society at large, delivering on greater human capital.2,4

For the first time in history, this generation will not live longer than the generation before it, worldwide.5 The chronic disease epidemic is driving much of this trend, with impacts being disproportionately felt by those experiencing adversity.6 Opportunities for thriving are becoming increasingly socially patterned. Evidence shows that strategic investments in early childhood are imperative for averting the onset of health challenges and mitigating their societal impacts.7 Yet Australian children on a persistently disadvantaged trajectory over early childhood have a seven‐fold increased risk of having poorer outcomes in multiple developmental domains by late childhood, compared with the most advantaged children.8

Although it might seem an unachievable goal, with the right political will and resource commitments, Australia could close the child equity gap within a generation. Perhaps more than any other time in the past decade, current federal and state agendas align with this aspiration, with the latest intergenerational report underscoring the need for urgency.4 Responding to current policy interests can inform priority areas and the intervention levers that could be considered. Some existing Australian policy interests include: Early Years Strategy,9 National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children,10 Entrenched Disadvantage Package,11 National Children's Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy,12 and Early Childhood Education and Care agendas.13

This article suggests a path forward that draws on the critical thinking of multidisciplinary leaders (across economics, health, education, social care, legislation and policy) and converges on key themes of “thinking and doing” that can and should inform the early years policy and research agenda for Australia. These collaborations are essential if Australian governments are prepared to deliver on closing the equity gap with the level of urgency required.

The road to equity needs to be paved with more than good intentions

Radical pragmatism — “a willingness to try whatever works, guided by an experimental mindset and commitment to empiricism and measuring results”14 — suggests the need to test and responsively change course as knowledge evolves. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has shown us that radical change is possible at speed and scale, especially with political will during a time‐sensitive period. Australian governments organised the development and distribution of vaccines, distributed payments to people to keep their jobs, doubled the basic income, housed the homeless, and provided access to telehealth across the country.15 This was possible because political leaders applied bipartisan political will to a crisis, allocated sufficient resourcing to move at pace, listened to community where needed and were prepared to fail and learn from these failings for the greater good of the population.

Researchers and policy makers need to stop focusing on only measuring the problem and start engaging in radically pragmatic approaches to policy and service delivery to address child inequities.14 Research has identified a range of promising early childhood interventions that are already delivered within existing Australian infrastructure and resourcing. For example, antenatal care, sustained nurse home visiting, early childhood education and care, parenting programs and the early years of school have individually been shown to have a positive impact, when delivered well.16,17,18 But their mutual and cumulative benefits are rarely considered in their design or delivery.17 A commitment to experimenting at speed will help identify new solutions to fill policy and service gaps. Governments need approaches that: (i) can move at speed; (ii) can scale when needed; (iii) are co‐designed; and (iv) are driven and monitored or evaluated by data and evidence.

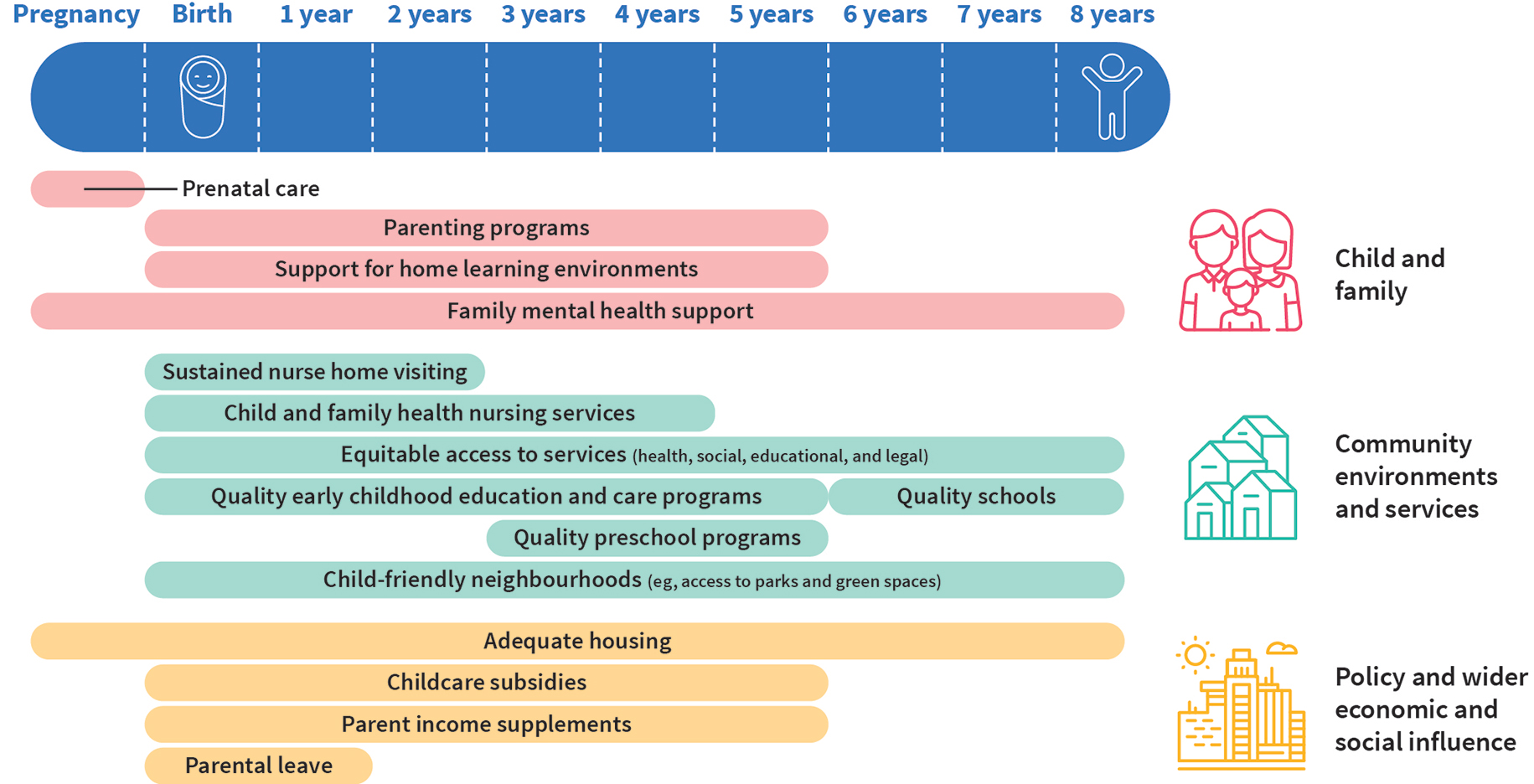

Achieving impact at the scale needed will require a coordinated approach that carefully considers the determinants that children need to thrive, both upstream (social determinants) and downstream (services and strategies),17,19 as well as collaborative efforts to address systemic barriers and mobilise resources (Box 1). This will be challenging to achieve and requires long term commitment, but with an actionable agenda grounded in the ideas of radical pragmatism, anything is possible.

The intricacy of inequity can be met with a modern and doable solution

Even excellent single early childhood intervention approaches are insufficient alone to overcome inequities.17,20 Truly closing the equity gap requires moving beyond the silver bullet thinking that remains pervasive in the traditional research and policy paradigm and stepping into complexity. To address the intricacy of inequity, there is a need for similarly complex intervention approaches. Combining or stacking multiple complementary cross‐portfolio interventions in the early years, including those addressing the structural determinants of health, that involve federal, state or territory, and local governments, is essential for reducing child inequities and improving outcomes.17,20,21,22,23 This should be a relatively straightforward selection of interventions that researchers and policy makers know work, as well as better use of existing education, health and social infrastructure to purposefully redress inequities (Box 2). Grounding this approach in principles of proportionate universalism will ensure the benefits of a universal service base while enabling tailoring to ensure the scale and intensity is proportionate to the level of need, as is required to effectively address inequities.24

The stack must: (i) achieve the greatest impact; (ii) be carefully considered across the life course; (iii) maximise existing resources and expenditure where possible; (iv) use data and indicators to drive system change; (v) enable rapid implementation through well resourced and agile co‐design processes; and (vi) stack all the way through the ecological path (ie, from individual through to policy change). There is much to be learned from innovative place‐based and community‐driven programs that are already putting these principles into practice through integrated service delivery programs with promising results, for example: Sure Start25 and Born in Bradford's Better Start26 (both United Kingdom), Head Start27 (United States), Better Beginnings, Better Futures28 (Canada), and Communities for Children29 (Australia).

It takes data to lend precision to action

Robust data systems and high quality key indicators are paramount to informing more precise and effective approaches to identifying, addressing and monitoring inequities. In Australia, there is increasing interest and investment in linking administrative data across diverse sectors. Linked administrative data assets, such as the Australian Government Personal‐Level Integrated Data‐Asset (PLIDA),30 the upcoming Life Course Data Initiative31 and the National Disability Data Asset,32 provide a time‐ and cost‐efficient opportunity to generate actionable policy‐relevant evidence. However, key data gaps (including limited data on the family environment, child outcomes and some priority population groups) as well as limitations surrounding data accuracy, completeness and timeliness can hinder our understanding of where and how to allocate resources to effectively address inequities.

There are opportunities to stack data sources by linking administrative data with well designed epidemiological studies collecting robust information that is not feasible to obtain through administrative data. The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children, which has been following the development of 5107 infants since May 2004,33 is an example of a population representative cohort that has been enhanced through significant data linkage. A recent example is Generation Victoria (GenV), a prospective whole‐of‐state multipurpose birth and parent cohort that began in October 2021;34 over 120 000 babies and parents have been recruited to date. GenV is representative of the state of Victoria, and thus, in most respects, Australia. Enhanced through extensive linkage to state and federal administrative data, GenV will have the richness and breadth of information needed to support the evaluation of policy‐relevant stacked interventions across the child's entire ecological system.

When combined with innovative causal analytic approaches, these kinds of data can be used to robustly test interventions that may not be timely, ethical, or feasible to test in the real world. It is important to consider how these types of data can be more widely shared to foster intersectoral collaboration and engage political and community leaders, advocates, researchers and service users, who are paramount to the conceptualisation and delivery of the stacked approach.

Conclusions

The agenda for children needs reframing. It is clear that almost anything can be achieved with sufficient resources alongside community and political will. About 72 000 Australian babies are born into adversity every year35 and their chance of a long, healthy and productive life is reduced. Children being born today should have more equitable adult outcomes than their parents, not less. There is a sense of urgency and momentum among researchers and policy makers. But there is also a sense of purpose. The time to act is now.

Box 1 – What needs to be done to address child inequities?

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Research |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Generate actionable evidence |

Produce robust evidence that can inform the design and implementation of interventions; decision makers need a repository of evidence detailing the optimal combinations of interventions for a given population, at the right time, intensity and duration to achieve maximum impact. |

||||||||||||||

|

Foster interdisciplinary collaborations |

Collaborate across disciplines, integrating insights from diverse fields such as health, education, social care, economics and policy. |

||||||||||||||

|

Consider social determinants of health |

Develop coordinated solutions that carefully consider the multidimensional determinants that drive inequities in children's health, development and wellbeing. |

||||||||||||||

|

Engage with consumers |

Actively involve consumers, service providers and communities in all stages of the research process, incorporating their priorities and perspectives to ensure that research outcomes are culturally appropriate, contextually relevant and inclusive. |

||||||||||||||

|

Advocate for policy change |

Work collaboratively with policy makers and advocacy groups to ensure that research is policy‐relevant and targets the needs of decision makers, and to stimulate policy thinking. |

||||||||||||||

|

Policy |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Establish multisectoral coordination mechanisms |

Platforms and mechanisms for activating and maintaining multisectoral partnerships around a shared vision for a better future for Australia's children will be critical for facilitating collaboration, coordination and reciprocal knowledge‐sharing across diverse sectors. |

||||||||||||||

|

Prioritise equity |

Addressing inequities requires designing policies and interventions with reduced disparities as an explicit outcome and establishing mechanisms to measure and monitor equity to promote accountability. |

||||||||||||||

|

Strategically allocate resources |

Prioritise investments in policies, programs and services that are known to help reduce inequities; this should be evidence informed. |

||||||||||||||

|

Address the structural determinants of inequities |

Address the underlying structural factors that drive inequities, such as income and taxation, access to health care and education, and racism; this requires structural change at the level of policy and constitution. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Collier L, Gregory T, Harman‐Smith Y, et al. Inequalities in child development at school entry: a repeated cross‐sectional analysis of the Australian Early Development Census 2009‐2018. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2020; 4: 100057.

- 2. Heckman J, Masterov D. The productivity argument for investing in young children. Review of Agricultural Economics 2007; 29: 446‐493.

- 3. Woolfenden S, Goldfeld S, Raman S, et al. Inequity in child health: the importance of early childhood development. J Paediatr Child Health 2013; 49: 365‐369.

- 4. Commonwealth of Australia. Intergenerational report 2023: Australia's future to 2063. The Treasury, Australian Government, 2023. https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2023‐intergenerational‐report (viewed Apr 2024).

- 5. Crimmins EM. Lifespan and healthspan: past, present, and promise. Gerontologist 2015; 55: 901‐911.

- 6. Sanderson M, Mouton CP, Cook M, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and chronic disease risk in the Southern Community Cohort Study. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2021; 32: 1384‐1402.

- 7. Campbell F, Conti G, Heckman J, et al. Early childhood investments substantially boost adult health. Science 2014; 343: 1478‐1485.

- 8. Goldfeld S, O'Connor M, Chong S, et al. The impact of multidimensional disadvantage over childhood on developmental outcomes in Australia. Int J Epidemiol 2018; 47: 1485‐1496.

- 9. Australian Government. The Early Years Strategy: discussion paper. Australian Government, 2023. https://engage.dss.gov.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/02/early‐years‐strategy‐discussion‐paper.pdf (viewed July 2024).

- 10. Commonwealth of Australia. Safe and Supported: the National Framework for Protecting Australia's Children 2021‐2031. Australian Government Department of Social Services, 2021. https://www.dss.gov.au/our‐responsibilities/families‐and‐children/programs‐services/protecting‐australias‐children (viewed Apr 2024).

- 11. Australian Government Department of Social Services. Entrenched disadvantage package. Australian Government, 2023. https://www.dss.gov.au/publications‐articles‐corporate‐publications‐budget‐and‐additional‐estimates‐statements/entrenched‐disadvantage‐package?HTML (viewed Oct 2023).

- 12. National Mental Health Commission. National children's mental health and wellbeing strategy. 2021. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/publications/national‐childrens‐mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐strategy‐full‐report (viewed Apr 2024).

- 13. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Report on Government Services 2023: early childhood education and care. Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2023. https://www.pc.gov.au/ongoing/report‐on‐government‐services/2023/child‐care‐education‐and‐training/early‐childhood‐education‐and‐care#ecec (viewed Apr 2024).

- 14. Gertz G, Kharas H. Radical pragmatism: policymaking after COVID [website]. Democracy, 2020. https://democracyjournal.org/arguments/radical‐pragmatism‐policymaking‐after‐covid/ (viewed Feb 2023).

- 15. Beale S, Burns R, Braithwaite I, et al. Occupation, worker vulnerability, and COVID‐19 vaccination uptake: analysis of the Virus Watch prospective cohort study. Vaccine 2022; 40: 7646‐7652.

- 16. Molloy C, Moore T, O'Connor M, et al. A novel 3‐part approach to tackle the problem of health inequities in early childhood. Acad Pediatr 2021; 21: 236‐243.

- 17. Molloy C, O'Connor M, Guo S, et al. Potential of ‘stacking’ early childhood interventions to reduce inequities in learning outcomes. J Epidemiol Community Health 2019; 73: 1078‐1086.

- 18. Rankin PS, Staton S, Potia AH, et al. Emotional quality of early education programs improves language learning: a within‐child across context design. Child Dev 2022; 93: 1680‐1697.

- 19. Goldfeld S, Gray S, Azpitarte F, et al. Driving precision policy responses to child health and developmental inequities. Health Equity 2019; 3: 489‐494.

- 20. Goldfeld S, Gray S, Pham C, et al. Leveraging research to drive more equitable reading outcomes: an update. Acad Pediatr 2022; 22: 1115‐1117.

- 21. Pearce A, Dundas R, Whitehead M, Taylor‐Robinson D. Pathways to inequalities in child health. Arch Dis Child 2019; 104: 998‐1003.

- 22. Halfon N, Russ S, Kahn R. Inequality and child health: dynamic population health interventions. Curr Opin Pediatr 2022; 34: 33‐38.

- 23. Goldfeld S, Moreno‐Betancur M, Gray S, et al. Addressing child mental health inequities through parental mental health and preschool attendance. Pediatrics 2023; 151: e2022057101.

- 24. Marmot M, Atkinson T, Bell J, et al. Fair society, healthy lives (The Marmot Review): strategic review of health inequalities in England post‐2010 [Executive Summary]. Secretary of State for Health, 2010.

- 25. Carneiro P, Cattan S, Ridpath N. The short‐ and medium‐term impacts of Sure Start on educational outcomes. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2024. https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024‐04/SS_NPD_Report.pdf (viewed Apr 2024).

- 26. Dickerson J, Bird PK, McEachan RR, et al. Born in Bradford's Better Start: an experimental birth cohort study to evaluate the impact of early life interventions. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 711.

- 27. Bailey M, Sun S, Timpe B. Prep school for poor kids: the long‐run impacts of Head Start on human capital and economic self‐sufficiency. Am Econ Rev 2021; 111: 3963‐4001.

- 28. Peters R, Bradshaw A, Petrunka K, et al. The Better Beginnings, Better Futures project: findings from Grade 3 to Grade 9. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2010; 75: 1‐176.

- 29. Muir K, Katz I, Edwards B, et al. The national evaluation of the Communities for Children initiative. Australian Government, Australian Institute of Family Studies, Family Matters, 2010 (No. 84).

- 30. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Person Level Integrated Data Asset (PLIDA). Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2023. https://www.abs.gov.au/about/data‐services/data‐integration/integrated‐data/person‐level‐integrated‐data‐asset‐plida (viewed Aug 2023).

- 31. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Life course data initiative. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/about/key‐priorities/life‐course‐data‐initiative (viewed June 2024).

- 32. Australian Government Department of Social Services. National disability data asset [website]. Australian Government Department of Social Services. https://www.ndda.gov.au/ (viewed June 2024).

- 33. Soloff C, Lawrence D, Johnstone R. Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Technical paper No. 1. Sample design. Australian Government, Australian Institute of Family Studies, 2005. https://growingupinaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/tp1.pdf

- 34. Wake M, Goldfeld S, Davidson A. Embedding life course interventions in longitudinal cohort studies: Australia's GenV opportunity. Pediatrics 2022; 149 Suppl 5: e2021053509R.

- 35. O'Connor M, Slopen N, Becares L, et al. Inequalities in the distribution of childhood adversity from birth to 11 years. Acad Pediatr 2020; 20: 609‐618.

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council Linkage Projects (LP190100921) and the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. Sharon Goldfeld is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Practitioner Fellowship (1155290). Contributing members of the Changing Children's Chances Investigator Group include: Margarita Moreno‐Betancur (Murdoch Children's Research Institute), Meredith O'Connor (Murdoch Children's Research Institute), Katrina Williams (Monash University), Susan Woolfenden (University of New South Wales), Hannah Badland (RMIT University), Naomi Priest (Australian National University), Francisco Azpitarte‐Raposeiras (Loughborough University, UK), and Gerry Redmond (Flinders University).

No relevant disclosures.