The known: Knowledge translation efforts in health research are intended to improve health and wellbeing through the application of research knowledge. Research done predominantly on Indigenous peoples has resulted on suboptimal improvements in Indigenous peoples’ health and wellbeing outcomes.

The new: Knowledge translation is inherent to Indigenous research practice. Knowledge translation in Indigenous health should move beyond Euro‐Western academic metrics and incorporate local knowledge holders. Researchers and institutions should be accountable for ensuring that knowledge translation is embedded throughout the research process.

The implications: Our findings identify effective examples of knowledge translation and offer ways to advance the field as essential in delivering sustainable health outcomes for Indigenous people through research and evaluation.

Knowledge translation refers to the processes, activities, and deliverables that convert research knowledge and findings into action: knowledge translation is ultimately what makes research matter. All ethical and impactful health research puts knowledge translation principles and plans into practice. In Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) has adopted the Canadian Institutes of Health Research definition of knowledge translation “as a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve health, provide more effective health services and products, and strengthen the health care system”.1,2 A wide range of strategies,3 tools, and training support the development and implementation of knowledge translation in health and medical research.4,5,6 While knowledge translation is not specific to Indigenous populations, it is inherent to the reciprocal practice of Indigenous methods and knowledge.

All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research must adhere to ethical codes of practice that recognise the pivotal role of knowledge translation as inherent to ethical research.1,7 Knowledge translation is articulated in the NHMRC principle of “respect” and the distribution of benefits within the principles of “reciprocity” and “equity”.1 The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council (AH&MRC) guidelines7 explicitly call for researchers to detail their knowledge translation plans to ensure that the conduct of research is accurate, meaningful, and offered back to the communities involved. While the definition and ethical application of knowledge translation is well established, knowledge is limited regarding specific strategies and activities that should be, and are being, applied in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and medical research.

In Indigenous health research contexts, how knowledge translation is understood, funded, and operationalised has been limited.8,9 A recent systematic review of effective knowledge translation in Indigenous health research around the world by members of this author team (authors MEMN, RM, SB, JS) found that few studies have evaluated or reported the benefits, impacts, or outcomes of research.8 The review found that research was most beneficial when Indigenous community members identified knowledge translation priorities, led or guided knowledge translation initiatives, and reflected local Indigenous values, culture, language, and strengths.8 Conversely, it was reported that the ongoing forms of colonisation were manifested in Euro‐Western knowledge translation by imposing Euro‐Western paradigms, using language that did not accurately reflect the lived realities of Indigenous peoples, and disregarding long existing ways of Indigenous knowledge sharing.8

Indigenous peoples have a long, ongoing, and comprehensive history of evidence‐based research, science and practice.10 However, racialised logic has prioritised Euro‐Western knowledge.11,12 Euro‐Western sciences were employed to justify colonialism, racism, and enslavement, with some discredited methods persisting into scientific discourse today.13,14,15,16 Colonial research approaches have actively excluded Indigenous peoples and their methodologies from academic spaces, within academic institutions, and privileged peoples, curriculum, and pedagogies that conform to colonial practices.17 As a result, what is known about, and the knowledge translated regarding Indigenous people are dominated by Euro‐Western and colonial ways of knowing, being, and doing.17,18

In upholding our positioning as Indigenous peoples, building on the systematic review findings,8 and acknowledging the need to overcome racialised logic in driving solutions, we aimed to better understand effective knowledge translation approaches and what is required to advance knowledge translation in health research with, for, and by Indigenous peoples.

Methods

As researchers and authors, we aim to conduct ourselves and facilitate Indigenous health research in a good way. The concept of working in a good way is central to any health or medical research. Author SB, as an Elder and teacher, prefaced the writing of this paper by emphasising the importance of working in a good way, sharing that the path to learning requires a transformative process. Learning through research, by definition, is transformative. Indigenous research incorporates practices and ideas that are part of medical professionals’ commitment to care for peoples’ journey to living a good life and having a good mind.19 The practice of doing things in a good way is ancestral knowledge passed on from one generation to another through Elders and knowledge keepers, which includes family, friends, and community through various means such as yarning, art, teaching, ceremony, and more. As authors, we came together and developed this article in the spirit of working together in a good way, with a collective commitment to advancing knowledge translation practices that help clear pathways to living a good life for Indigenous peoples. The reporting of this study adhered to the CONSolIdated critERia for strengthening the reporting of health research involving Indigenous Peoples (CONSIDER) statement20 (Supporting Information 1) and the Yarning Method.21

Data collection

A 1.5‐hour knowledge translation workshop was held at the 2023 Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health Conference, open to all conference attendees. The workshop included Indigenous researchers from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Papua New Guinea sharing definitions and examples of knowledge translation in their Indigenous contexts, followed by facilitated discussion. A summary of the recent systematic review findings was provided to all participants (Supporting Information 2).

During the facilitated discussions, participants were asked to answer the following questions anonymously in an online polling application (Slido):- What is your favourite example of knowledge translation?

- What is needed for knowledge translation in Indigenous research contexts?

The anonymous responses were visible on a large screen, and participants were seated around tables in groups of five to ten people. Each participant was asked to share an example at their respective tables before inviting participants to share their examples with everyone attending the workshop. Participants at each table recorded notes from their table group discussions on a large sheet of paper that was collected by workshop facilitators at the end. In addition, a research team member (author MMN) took notes throughout the workshop. The data collection process facilitated a collaborative process in which findings and ideas were discussed through knowledge generation and sharing between researchers and participants. No identifying information was collected and all responses were stored securely, and only available to the research team.

Analysis

Poll responses and participants’ and research team members’ notes were gathered at the Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health Conference. Collaborative yarning22 between the researchers was central to the analysis process which prompted reflexive analysis and meaning making from the responses. Drawing on methods of reflexive thematic analysis,23 author MMN gathered all of the notes and participant responses, and assigned inductive codes. The raw responses, grouped by the initial codes, were collaboratively discussed and revised by the research team members in Zoom meetings, and agreed on proposed themes. Based on the themes, a summary graphic was developed. The research team met face to face and online throughout the analysis process to review and refine the themes. This collaborative approach to developing, reviewing, and refining themes helped to uphold Indigenous research principles and practices by sharing knowledge and ideas.10,22,24

Positionality

This work was led by Indigenous interests, needs, and rights as Indigenous peoples, consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,25 AH&MRC guidelines,7 and just as wise and ethical practices expect: “nothing about us without us”.26 In Indigenous health research, more and more scholarship on Indigenous research is held to a higher standard of transparency regarding relationality and acknowledging community accountability and responsibilities, authors’ relationships with the research and each other, and intentions behind the research. This is a foundational matter of ontology and epistemological consideration, shaping the paradigm for this program of work and not merely a matter of identity.27,28 This article was conceptualised with Indigenous leadership and engagement, including our Indigenous lived experiences (MK, RM, SB, JM, JS, PS, TC) and non‐Indigenous experiences (MEMN, MMN) in Australia (MK, TC, RM, JM, PS), and Canada (MEMN, MMN, JS, SB). Our research expertise includes commercial tobacco control (MK, RM, TC), ethics (MK), knowledge translation (JM, MK, JS, MEMN, RM), and maternal health (JS, MEMN, MK, JM).

Ethics approval

This study upholds ethical values, principles and practices and was developed in collaboration with Indigenous researchers and community members. The project upholds the CONSIDER statement20 (Supporting Information 1). The study was approved by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies HREC (REC‐0113). Implied consent to participation was obtained from all participants.

Results

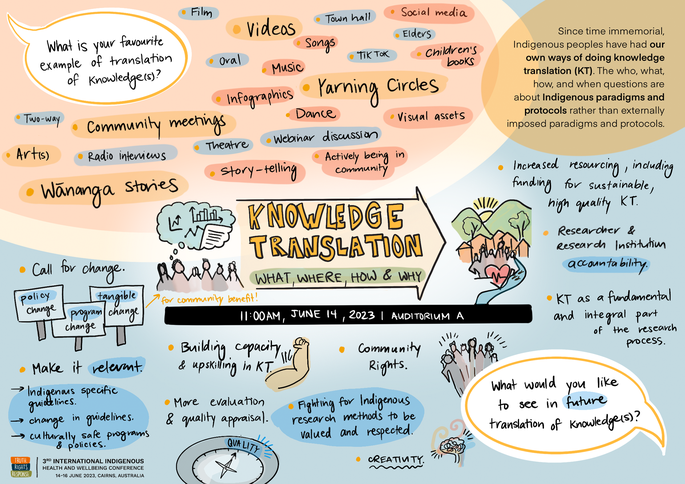

About 70 people, predominantly Indigenous people involved in research and Indigenous health researchers, participated in the workshop and shared their experiences and recommendations for knowledge translation. Forty‐four participants submitted 90 responses to a poll question asking people to enter their favourite examples of knowledge translation. A word cloud with the most frequent responses in the centre with larger font was created (Box 1). The most frequent responses were Yarning circles, videos, stories, Wānaga, community meetings, art, visual storytelling, and infographics and illustrations.

During the workshop, key messages were depicted in an illustration (Box 2). After reviewing all responses, four themes were developed from participants’ discussions on knowledge translation:- Knowledge translation is fundamental to research and upholding community rights.

- Knowledge translation approaches must be relevant to local community needs and ways of mobilising knowledge.

- Researchers and research institutions must be accountable for ensuring knowledge translation is embedded, respected, and implemented in ways that address community priorities.

- Knowledge translation must be planned and evaluated in ways that reflect Indigenous community measures of success.

Knowledge translation is fundamental to research and upholding community rights

Participants asserted that knowledge translation is a fundamental and integral part of research that must be embedded by planning, revising, and implementing throughout the research process from the earliest stages of project development. Participants emphasised and affirmed relational aspects of knowledge translation, including the importance of developing trust, listening carefully, being creative, and thinking outside of the common research knowledge translation box. Participants highlighted how knowledge translation offers sustainable approaches and impacts that extend well beyond a study when it is embedded as an integral part of the research.

Knowledge translation was discussed as a way to help uphold community rights in research practice. Further, participants linked discussion of knowledge translation with ethical research practices that must be upheld in knowledge translation planning and research processes. Integral to this process were Indigenous community rights to:- govern how their data are accessed, used, and shared;

- be respected, recognised, and valued for the wisdom of Indigenous knowledge holders;

- recognition and funding of yarning and community meetings as knowledge translation methods; and

- prioritise Indigenous knowledges and ways of being, knowing, and doing in research, including knowledge translation.

Knowledge translation approaches must be relevant to local community needs and ways of mobilising knowledge

Participants shared examples of how local Indigenous health workers and practitioners are trusted and effective people for mobilising knowledge, as well as for advising on the best local knowledge translation messaging and methods. They noted the undervaluation of Indigenous, community‐led knowledge translation approaches, such as community feasts and gatherings, by academic researchers and institutions, who often prioritise more traditional formats, such as conferences and publications. The participants called for greater recognition and support for community‐driven methods, highlighting the importance of adequate funding for cultivate sustainable relationships. Participants emphasised that discussion and planning of which knowledge translation methods and content best suit community and inform decision making and policy changes must be embedded in the earliest stage of research development.

Researchers and research institutions must be accountable for ensuring that knowledge translation is embedded, respected, and implemented in ways that address community priorities

Participants detailed the importance of researcher, research institution and funding bodies accountability, to ensure knowledge translation activities are embedded, respected, and meaningfully implemented in ways that address community priorities. Participants highlighted the challenge for research to influence sustainable change when funding opportunities only support pilot or developmental research. Additionally, they emphasised the need for knowledge translation capacity building for researchers. Participants advocated cultural safety training and humility for academics and those involved in reviewing Indigenous research, such as publication and proposal reviewers.

Knowledge translation must be planned and evaluated in ways that reflect Indigenous community measures of success

Participants emphasised the importance of Indigenous communities leading and informing knowledge translation priorities and measures of knowledge translation success when involved in research. If knowledge translation is to have long term impacts and benefits, monitoring how knowledge translation is implemented and benefits Indigenous people is crucial. In order to improve Indigenous health through research, several participants highlighted that knowledge translation plans and efforts must be continuously assessed and evaluated. For example, funding applications and plans should be reviewed to ensure knowledge translation has been undertaken and community priorities met.

Discussion

The development of new knowledge alone will not lead to health improvements.29 The translation of research findings is a critical component of diligent research practices. All health and medical research, during development, must consider dissemination strategies and how findings can inform policy and practice. Research conducted with Indigenous peoples must also uphold ethics and integrity and return research to Indigenous people in a meaningful way. Indigenous peoples have and continue to advance knowledge, knowledge systems, and consequently wise practices,10,28 and should be sought to guide appropriate knowledge translation. Knowledge translation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research is a somewhat emergent field, drawing from knowledge generated in Canada. Our study aimed to contribute to national discussions of knowledge translation for and by Indigenous people, including work in progress to report specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.30 While the study was not designed to be representative of any population and participant characteristics were not reported, we identified examples of effective knowledge translation and ways to advance delivering sustainable improvements in health outcomes for Indigenous people through research.

We found that knowledge translation is integral to research planning and implementation. While the NHMRC acknowledges knowledge translation, it currently does so only in the Indigenous Research Excellence criteria.31 Researchers are not required to report on Indigenous knowledge translation planning or implementation. Conversely, the Lowitja Institute embeds knowledge translation planning in its application process for major grants and scholarship funding, and offers funding to implement knowledge translation. Researchers must submit a comprehensive knowledge translation plan that is externally peer‐reviewed and assessed by Indigenous people to obtain knowledge translation funding. Our findings support knowledge translation funding being offered by all national funding bodies. Researchers should have access to funding for knowledge translation, with comprehensive planning and implementation, to uphold best practice knowledge translation for health research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian research funders acknowledge that research must be translatable and have impact. Our findings highlight the connection between knowledge translation and research impact, whereby Indigenous peoples can apply research findings to their local contexts.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have the right to Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. The Australian government is currently developing a public service framework for the governance of Indigenous data.32 Our findings indicate that knowledge translation is integral to Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. Researchers working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must understand and uphold Indigenous data sovereignty and governance.33

Our findings accentuate the need for Indigenous methodologies to be valued and respected in academic fields. Within Indigenous methodologies, core values associated with knowledge translation exist. While calls to privilege Indigenous methodologies in health research are not new,8,10,17,19 participants in our study regarded the application of Indigenous methodologies as integral to effective knowledge translation, which in turn leads to greater uptake of research findings in policy and practice.34 It is essential that Indigenous knowledge systems are embedded in research practices that aim to improve Indigenous health outcomes. This can help overcome systemically racist colonial structures and move beyond Euro‐Western knowledge and academic metrics if we are to improve health outcomes. Indigenous people have the right to the research and outcomes generated from their knowledge. However, it must be delivered in a way that is meaningful to Indigenous people, as indicated by findings overseas that local knowledge translation has most impact.8 Our findings support localised decision making; participants articulated the importance of local Aboriginal health workers and practitioners, their knowledge, skills, and networks being well placed to facilitate knowledge translation strategies and activities. When planning knowledge translation, researchers should also identify knowledge translation implementors and ensure appropriate funding for the work.

We found that effective knowledge translation requires Indigenous, community‐led knowledge translation approaches that include a diverse range of face‐to‐face, online, arts‐based, and interactive preferences (Box 2). These approaches coincide with the Indigenous‐led best practice knowledge translation frameworks and practices recently described by Lowitja Institute.35 These findings indicate the need to move beyond Euro‐Western academic knowledge translation metrics and those used in academic literature,8 and to position Indigenous peoples at the centre of knowledge translation planning and practice. Our findings are consistent with earlier findings8 that Indigenous knowledge translation offers unique and important research metrics.

It is critical that researchers plan, implement, and report their knowledge translation practices for transparency of ethical research, support advances in the field, and ultimately improve health and wellbeing. Reporting guidance, such as the international CONSIDER statement, provides a checklist for the reporting of health research involving Indigenous peoples.20 Domain 8 of the statement acknowledges the social value and accountability to Indigenous communities of knowledge translation. Specifically, researchers are asked to outline their dissemination of research outputs, and process for knowledge translation to support Indigenous health improvement. Recent publications by our research team have adhered to the CONSIDER statement, reporting guidance and the transparency of knowledge translation practice.36,37 Further, ethical publishing practices by journals that require accurate reporting of research practices, including knowledge translation, have been recommended.38

The workshop participants highlighted structural and interpersonal areas for improvement, emphasising a need for all institutions, funding bodies, and academics to recognise responsibilities for Indigenous‐led knowledge translation development, implementation, and evaluation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers have called for a reframing of health research to enhance the benefits of research for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.29,39 Research is also underway to examine the implementation of ethical health research practice from the perspectives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.40 All institutions, funding bodies, and academics need to reflect and revise ways of conducting research, with the aim of improving Indigenous health as we move toward challenging the colonial knowledge production discourse. Knowledge translation is an integral part of the research process, ensuring that valuable insights generated by research reach and benefit the intended audiences.41 By embedding knowledge translation planning, implementation, and evaluation criteria in funding applications, funding bodies can systematically contribute to the effectiveness and impact of research and evaluation. Further, this will help to enhance community engagement and collaboration, optimise resource allocation, and improve long term sustainability and accountability, better ensuring continuous improvement in knowledge translation processes and outcomes.

Limitations

Our study was not designed to reach consensus or assess variability of responses according to the demographic characteristics of participants. It prioritised collective Indigenous wisdom and leadership, which may be deemed a limitation in some Euro‐Western knowledge systems.

Conclusion

Knowledge translation is fundamental to making research matter. Further, embedding knowledge translation planning and practice is critical to ethical research. Knowledge translation must be embedded in all stages of research practice to uphold Indigenous community rights to knowledge and privileging of our knowledge systems. Effective knowledge translation approaches include a diverse range of Indigenous‐led face‐to‐face, online, arts‐based, and interactive preferences. Despite the ongoing nature and impacts of colonisation, Indigenous peoples have a long and comprehensive history of evidence‐based research, science, and practice. There is an increasing need to move beyond Euro‐Western knowledge, Euro‐Western academic metrics, and colonial structures if we are to meaningfully improve health outcomes. Institutions, funding bodies, and academics should embed structures that uphold Indigenous knowledge translation and overcome racist colonial systems and structures to better ensure research is relevant to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. We join calls for reimaging health and medical research that also embeds Indigenous knowledge translation as the prerequisite for knowledge production that makes research matter.

Data sharing

In line with Indigenous data sovereignty and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ethical research principles, no data sharing is available from this study.

Received 21 January 2024, accepted 7 May 2024

- Michelle Kennedy (Wiradjuri)1,2

- Melody Morton Ninomiya3

- Maya Morton Ninomiya3

- Simon Brascoupé (Anishinabeg/Haudenausanee)4

- Janet Smylie (Mѐtis)5

- Tom Calma (Kungarakan, Iwaidja)6,7

- Janine Mohamed (Narrunga Kaurna)8

- Paul J Stewart (Taungurung)8

- Raglan Maddox (Bagumani, Modewa)9

- 1 The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

- 2 Lowitja Institute, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Canada

- 4 University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Canada

- 5 Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada

- 6 University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

- 7 The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 8 The University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT

- 9 National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Newcastle, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Newcastle agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

We acknowledge that the workshop for this study was conducted on the unceded lands of the Gimuy Walubara Yidinji and Yirrganydji peoples and pay respect to the Elders and enduring caretakers of the lands, seas, sky and waterways. We acknowledge all Indigenous peoples as the knowledge holders and pay respect to their wisdom and processes for generative knowledge productions and knowledge sharing. We acknowledge the Indigenous knowledge that informed this work. To our knowledge, the following references report Indigenous‐led research: 7–10, 12, 17, 18, 20, 22–26, 28–30 and 33–41.

Michelle Kennedy is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (1158670). Minor costs associated with the workshop were covered by the Canada Research Chair in Community‐Driven Knowledge Mobilization and Pathways to Wellness of Melody Morton Ninomiya (CRC‐2021‐00256).

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. National Health and Medical Research Council. Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Aug 2018. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about‐us/resources/ethical‐conduct‐research‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐peoples‐and‐communities (viewed Jan 2024).

- 2. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. About us: knowledge translation definition. Updated July 2016. https://www.cihr‐irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html#2 (viewed Mar 2024).

- 3. Zhao N, Koch‐Weser S, Lischko A, Chung M. Knowledge translation strategies designed for public health decision‐making settings: a scoping review. Int J Public Health 2020; 65: 1571‐1580.

- 4. Cochrane Training. Cochrane training online learning knowledge translation, n.d. https://training.cochrane.org/online‐learning/knowledge‐translation (viewed Mar 2024).

- 5. SickKids. Knowledge translation training and resources. 2022. https://www.sickkids.ca/en/learning/continuing‐professional‐development/knowledge‐translation‐training (viewed Feb 2024).

- 6. Khan S, Timmings C, Moore JE, et al. The development of an online decision support tool for organizational readiness for change Implement Sci 2014; 9: 56.

- 7. AH&MRC Ethics Committee. AH&MRC ethical guidelines: key principles (2020) V2.0, 2020. https://www.ahmrc.org.au/resource/nsw‐aboriginal‐health‐ethics‐guidelines‐key‐principles/ (viewed May 2024).

- 8. Morton Ninomiya ME, Maddox R, Brascoupé S, et al. Knowledge translation approaches and practices in Indigenous health research: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2022: 301: 114898.

- 9. Kinchin I, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, et al. Does Indigenous health research have impact? A systematic review of reviews. Int J Equity Health 2017; 16: 52.

- 10. Smith LT. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples. New York: Zed Books, 1999.

- 11. Zuberi T, Bonilla‐Silva E, editors. White logic, white methods: racism and methodology. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008.

- 12. Rigney LI. Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: a guide to Indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Review 1999; 14: 109‐221.

- 13. Roberts DE. Abolish race correction. Lancet 2021; 397: 17‐18.

- 14. Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE. The racist “one drop rule” influencing science: it is time to stop teaching “race corrections” in medicine. Adv Physiol Educ 2021; 45: 644‐650.

- 15. Cerdeña JP, Plaisime MV, Tsai J. From race‐based to race‐conscious medicine: how anti‐racist uprisings call us to act. Lancet 2020; 396: 1125‐1128.

- 16. Anderson MA, Malhotra A, Non AL. Could routine race‐adjustment of spirometers exacerbate racial disparities in COVID‐19 recovery? Lancet Respir Med 2021; 9: 124‐125.

- 17. Battiste M. Indigenous knowledge and pedagogy in First Nations education: a literature review with recommendations. Ottawa: National Working Group on Education, 2002. https://www.nvit.ca/docs/indigenous%20knowledge%20and%20pedagogy%20in%20first%20nations%20education%20a%20literature%20review%20with%20recommendations723103024.pdf (viewed Jan 2024).

- 18. Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, second class treatment: the role of racism in the health and well‐being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Toronto: Wellesley Institute, 2015. https://www.wellesleyinstitute.com/wp‐content/uploads/2015/02/Summary‐First‐Peoples‐Second‐Class‐Treatment‐Final.pdf (viewed Jan 2024).

- 19. Smylie J, Olding M, Ziegler C. Sharing what we know about living a good life: Indigenous approaches to knowledge translation. J Can Health Libr Assoc 2014; 35: 16‐23.

- 20. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving Indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 21. Kennedy M, Maddox R, Booth K, et al. Decolonising qualitative research with respectful, reciprocal, and responsible research practice: a narrative review of the application of Yarning method in qualitative Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Int J Equity Health 2022; 21: 134.

- 22. Bessarab D, Ng'andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. Int J Crit Indigenous Studies 2010; 3: 37‐50.

- 23. Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis: a practical guide. London: SAGE, 2022.

- 24. Weber‐Pillwax C. Indigenous research methodology: exploratory discussion of an elusive subject. Journal of Educational Thought 1999; 33: 31‐45.

- 25. Australian Human Rights Commission. UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. 2007. https://humanrights.gov.au/our‐work/un‐declaration‐rights‐indigenous‐peoples‐1 (viewed Mar 2024).

- 26. Marsden N, Star L, Smylie J. Nothing about us without us in writing: aligning the editorial policies of the Canadian Journal of Public Health with the inherent rights of Indigenous peoples. Can J Public Health 2020; 111: 822‐825.

- 27. Poirier B, Haag D, Soares G, Jamieson L. Whose values, what bias, which subjectivity?: The need for reflexivity and positionality in epidemiological health equity scholarship. Aust N Z J Public Health 2023; 47: 100079.

- 28. Galla CK, Holmes, A. Indigenous thinkers: decolonizing and transforming the academy through Indigenous relationality. In: Cote‐Meek S, Moeke‐Pickering T, editors. Decolonizing and indigenizing education in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 2020; pp. 51‐72.

- 29. Bainbridge R, Tsey K, McCalman J, et al. No one's discussing the elephant in the room: contemplating questions of research impact and benefit in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian health research. BMC Public Health 2015; 15: 696.

- 30. Brinckley M‐M, Bourke S, Watkin Lui F, Lovett R. Knowledge translation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research contexts in Australia: scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022; 12: e060311

- 31. National Health and Medical Research Council. Funding rules involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health‐advice/aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health/funding‐rules‐involving‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐people (viewed May 2024).

- 32. National Indigenous Australians Agency. Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. APS‐wide framework for Indigenous data and governance, Canberra 2023. https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource‐centre/framework‐governance‐indigenous‐data (viewed May 2024).

- 33. Lovett R, Lee V, Kukutai T, et al. Good data practices for Indigenous data sovereignty and governance. In: Daly A, Devitt SK, Mann M, editors. Good data. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2019: pp. 26‐36.

- 34. Sinclaire M, Schultz A, Linton J, McGibbon E. Etuaptmumk (Two‐Eyed Seeing) and ethical space: ways to disrupt health researchers’ colonial attraction to a singular biomedical worldview. Witness 2021; 3: 57‐72.

- 35. Wiiliams M, editor. Profiling excellence: Indigenous knowledge translation. Lowitja Institute, Aug 2021. https://www.lowitja.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/05/LowitjaKT_Report_final22.pdf (viewed Jan 2024).

- 36. Kennedy M, Longbottom H. Doing “deadly” community‐based research during COVID‐19: the Which Way? study [editorial]. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 86‐87. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/217/2/doing‐deadly‐community‐based‐research‐during‐covid‐19‐which‐way‐study

- 37. Kennedy M, Maddox R. Miilwarranha (opening): introducing the Which Way? study. Med J Aust 2022; 217(2 Suppl): S3‐S5. https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/2022‐07/MJA%20217_2_18%20July_Suppl.pdf

- 38. Maddox R, Drummond A, Kennedy M, et al. Ethical publishing in “Indigenous” contexts. Tob Control 2023; https://doi.org/10.1136/tc‐2022‐057702 [online ahead of print].

- 39. Watego C, Whop LJ, Singh D, et al. Black to the future: making the case for indigenist health humanities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 8704.

- 40. McGuffog R, Chamberlain C, Hughes J, et al. Murru Minya: informing the development of practical recommendations to support ethical conduct in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research: a protocol for a national mixed‐methods study. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e067054.

- 41. Ball J, Janyst P. Enacting research ethics in partnerships with Indigenous communities in Canada: “do it in a good way”. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2008; 3: 33‐51.

Abstract

Objectives: To better understand what knowledge translation activities are effective and meaningful to Indigenous communities and what is required to advance knowledge translation in health research with, for, and by Indigenous communities.

Study design: Workshop and collaborative yarning.

Setting: Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health Conference, Cairns, June 2023.

Participants: About 70 conference delegates, predominantly Indigenous people involved in research and Indigenous health researchers who shared their knowledge, experiences, and recommendations for knowledge translation through yarning and knowledge sharing.

Results: Four key themes were developed using thematic analysis: knowledge translation is fundamental to research and upholding community rights; knowledge translation approaches must be relevant to local community needs and ways of mobilising knowledge; researchers and research institutions must be accountable for ensuring knowledge translation is embedded, respected and implemented in ways that address community priorities; and knowledge translation must be planned and evaluated in ways that reflect Indigenous community measures of success.

Conclusion: Knowledge translation is fundamental to making research matter, and critical to ethical research. It must be embedded in all stages of research practice. Effective knowledge translation approaches are Indigenous‐led and move beyond Euro‐Western academic metrics. Institutions, funding bodies, and academics should embed structures required to uphold Indigenous knowledge translation. We join calls for reimaging health and medical research to embed Indigenous knowledge translation as a prerequisite for generative knowledge production that makes research matter.