Lifestyle factors — smoking, alcohol consumption, inadequate dietary levels of fruit and vegetables — are major risk factors for chronic medical conditions.1 The importance of clinicians encouraging people to modify their lifestyles is emphasised in many guidelines.2 A study that included 4716 American adults found that patient‐reported lifestyle advice from their doctors was associated with corresponding behavioural changes (weight reduction, increased physical activity).3 How often Australian general practitioners provide their patients with lifestyle advice and whether such advice is effective are unknown.

To investigate these questions, we undertook a secondary analysis of data collected by the 2020–21 National Health Survey, a nationally representative Australian Bureau of Statistics household survey.4 The survey included questions about demographic and socio‐economic characteristics, health conditions, lifestyle risk factors and behaviours, and health care services use. Participants were asked whether they had received lifestyle advice from general practitioners during the past twelve months — including about reducing or quitting smoking; drinking alcohol in moderation; reaching a healthy weight; increasing physical activity; and eating healthy food or improving diet — and about their alcohol consumption, smoking, and eating behaviour (composite of fruit and vegetable consumption) compared with twelve months ago.4 Sampling weights were applied to responses to estimate proportions weighted to the total Australian population. We examined associations between receiving lifestyle advice from general practitioners and changed behaviour in logistic regression analyses adjusted for potential confounders, using R 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing); we report adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee approved the study (CD03279).

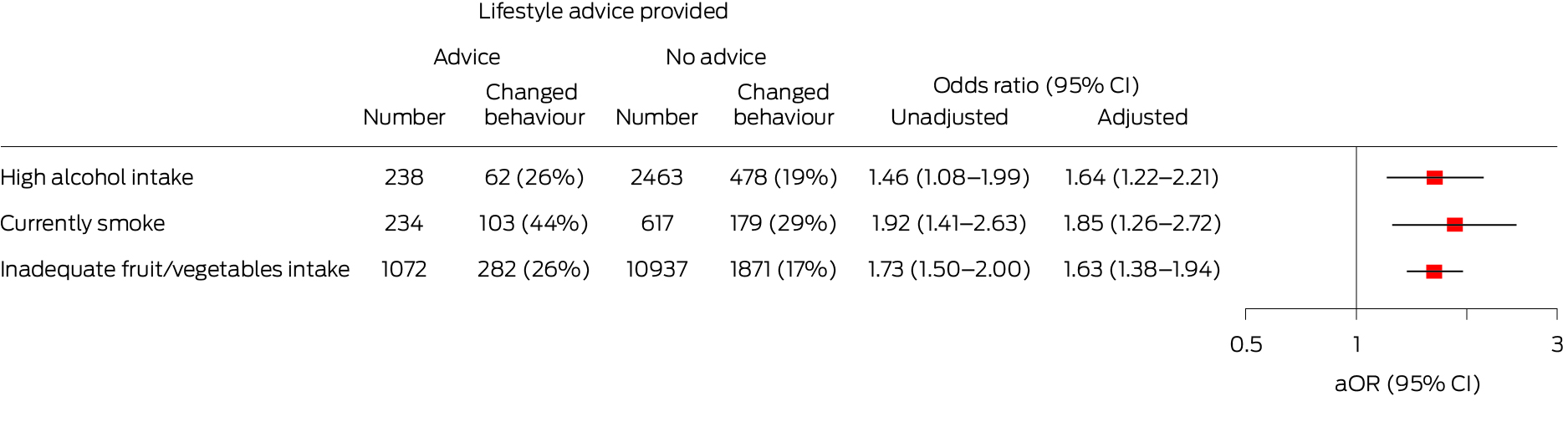

Of 13 281 survey respondents (7026 women, 50.5%) (Supporting Information, table 1), 2701 reported that their alcohol intake exceeded the recommended maximum level (20.1%), 851 currently smoked (9.1%), and 12 009 did not meet the minimum recommended combined intake of fruit and vegetables (91.9%) (Supporting Information, table 2). Of all respondents who reported exceeding recommended alcohol consumption limits, 238 had been advised to reduce it (8%), and 540 had reduced their alcohol use over the past twelve months (21%). Of 804 people who smoked, 228 had been advised to quit (27%), and 282 had reduced their smoking levels over the past twelve months (34%). Of all respondents with lower than recommended fruit and vegetable consumption, 1072 had been advised to increase it (9%), and 2153 had improved their consumption over the past twelve months (19%) (Supporting Information, table 3). Respondents who had received lifestyle advice from general practitioners were more likely to change their behaviour than those who had not (alcohol intake: aOR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.22–2.21; smoking: aOR, 1.85; 95% CI, 1.26–2.72; diet: aOR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.38–1.94) (Box).

Limitations to our study include the fact that we examined national health survey data, self‐reported information collected at a single time point (snapshot or cross‐sectional); our findings are therefore subject to recall and social desirability biases, and should be interpreted cautiously.

We found that lifestyle advice from general practitioners may influence their patients’ health‐related behaviour, but the proportions of people who recalled receiving their advice were small. This finding is similar to those of studies in the United States3 and England.5 As general practitioners may not have time to deliver brief lifestyle interventions for all their patients,6 interventions that prioritise effective lifestyle advice are needed.

Box – Lifestyle advice from general practitioners and positive changes in lifestyle behaviours during the past twelve months: logistic regression analyses, unadjusted and adjusted*

aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.Adjusted for socio‐demographic factors (age, sex, marital status, education level, income level, state/territory, residential remoteness); clinical factors (self‐reported medical conditions: arthritis, asthma, back pain, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, mental conditions); and lifestyle factors (body mass index, alcohol intake level, smoking, fruit and vegetable intake).

Received 14 August 2023, accepted 16 November 2023

- 1. GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020; 396: 1223‐1249.

- 2. US Preventive Services Task Force; Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without cardiovascular disease risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2022; 328: 367‐374.

- 3. Williams AR, Wilson‐Genderson M, Thomson MD. A cross‐sectional analysis of associations between lifestyle advice and behavior changes in patients with hypertension or diabetes: NHANES 2015–2018. Prev Med 2021; 145: 106426.

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data items. In: National Health Survey: first results methodology, 2020–21. 21 Mar 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/methodologies/national‐health‐survey‐methodology/2020‐21 (viewed Oct 2023).

- 5. Henry JA, Jebb SA, Aveyard P, et al. Lifestyle advice for hypertension or diabetes: trend analysis from 2002 to 2017 in England. Br J Gen Pract 2022; 72: e269‐e275.

- 6. Albarqouni L, Montori V, Jørgensen KJ, et al. Applying the time needed to treat to NICE guidelines on lifestyle interventions. BMJ Evid Based Med 2023; 28: 354‐355.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Bond University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Bond University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Data sharing:

The data we analysed for this report are publicly available.

This study was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant (2008379). The funder played no role in the planning, writing, or publication of this study.

No relevant disclosures.