The historical and political consequences of colonisation have had an enduring impact on the social determinants of the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.1 The disruption of traditional ways of life has led to the high prevalence of chronic disease, associated with psychosocial factors, such as meaninglessness, alienation, and loss of culture, that have both harmed the social and emotional health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and influenced behaviours directly related to their physical health.2

In the most recent National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (2018–19), 46% of First Nations people reported one or more chronic conditions,3 higher than in 2012–13 (40%).4 Such statistics are often cited when describing the health of Indigenous Australians, but the social determinants of their health have received less attention.2 As the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been shaped by historical, socio‐cultural, and political factors that affect their health,4 the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families may not be met if their unique social and political context is not considered.5 To better understand how social factors have affected the health of Indigenous people in Australia, it is important to consult local communities and involve them in designing solutions that meet their needs.6

The specific needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have been overlooked by parental support program research in Australia.4 The restricted support options for Indigenous parents are a problem,4 and their parenting methods are neither adequately understood nor incorporated into policy and practice.7 The separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families and the dispossession of the traditional owners of Country have had trans‐generational effects. Further, the forced relocation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to missions and stations has restricted parents in their traditional roles as carers, teachers, and leaders.7 Not meaningfully consulting Indigenous families has undermined understanding of the unique position of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents with respect to their children.7

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men play roles in child rearing that are different to those of other fathers in Australia.8 As opportunities for Indigenous men to fulfil their traditional family and community roles and responsibilities have been disrupted,8 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men need to be empowered as fathers and father figures.9 Earlier research has highlighted the benefits of engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers with targeted parenting programs,4 and a scoping review found that they can be beneficial for both fathers and their children.4 However, the authors acknowledged that their review was unlikely to be of sufficient breadth to be generalisable to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers.4

The participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers in randomised control trials of interventions for improving child health or wellbeing has not been quantified. Further, whether Indigenous people were consulted when designing parenting programs or the programs were tailored to meet the cultural needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants has not been examined.

We therefore undertook a review of published studies relevant to three research questions:

- To what extent are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents included in trials of parenting programs in Australia?

- To what extent are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers involved in trials of parenting programs in Australia?

- Do assessments of parenting programs assess whether they are culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

Methods

The conduct and reporting of this scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA‐ScR) statement.10 Two Aboriginal researchers were involved in all stages of the review. The research team received cultural guidance from the University of Newcastle Board of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education and Research (BATSIER). The scoping review was unanimously endorsed by the University of Newcastle Aboriginal Health Research Panel.

Eligibility criteria

We included publications in English in peer‐reviewed journals that reported quantitative outcomes for Australian randomised control trials (RCTs) of parenting programs in which the participants were parents or caregivers of children under 18 years of age. We considered only RCTs that included an interactive parent component (eg, family counselling sessions, home tasks for parents and their children, parent information nights), and not studies in which parents were passively involved in the intervention (eg, received newsletters or text messages). We included studies that measured at least one outcome related to child health, health behaviour, or wellbeing (Supporting Information, section 1).

Information sources and search strategy

We used a standardised protocol to search for relevant studies in MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Scopus: {parent* OR mother OR father OR famil* OR mum OR dad OR grandparent} NEAR/5 {program* OR intervention in Title Abstract Keyword} AND {Australia* in All Text}. That is, we searched for articles that included at least one term from each of the categories “participants” and “mode of delivery” in the title, abstract, or keywords, and the matching terms were within five words of each other, and included Australia* anywhere in the article. When the database allowed it, we applied the following search limits: “English language”, “human”, “RCT/randomised trial”, “Country: Australia”, and “peer reviewed”.

Publication selection

After removing duplicate records from our search results, three authors independently tested the title/abstract screening eligibility criteria for a sample of ten articles, using a spreadsheet based on the eligibility criteria. In cases of disagreement, a fourth author mediated and facilitated a group discussion until consensus was achieved. Three authors then screened the title and abstract of each retrieved record in a standardised, non‐blinded manner.

The full text of potentially relevant articles was retrieved for assessment, including those for which eligibility could not be determined by screening the title and abstract. Three authors then independently screened each article using an “include, exclude, or unsure” approach; a fourth author resolved disagreements by discussion until consensus was achieved. A pilot test of the inclusion criteria ensured that this phase of the screening process was satisfactory.

Data extraction

The data extraction template was adapted from a manual used for a systematic review of trials investigating the involvement of fathers in the treatment and prevention of obesity in children.11 Coders extracted key data items into a digital coding form using checkboxes or free text boxes: identifying details (study author, location), intervention details (mode of delivery, targeted outcomes), and participant details (number of participating parents, number of participating fathers, number of participating parents who were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people). For some items, additional notes were provided to improve agreement between coders (Supporting Information, section 2). The template was piloted by the authors using a random selection of ten eligible articles. They clarified ambiguous items by discussion, and this process was repeated several times to improve agreement before the template was finalised.

For each article, two authors independently extracted the required information. In a coding pilot test, each author coded ten publications according to the instruction manual; a third author resolved discrepancies by reference to the instruction manual and the article. Once consensus was reached, each of the remaining articles was coded by one of the coders. Unless specified, we did not assume that a participating parent was Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander because a child was reported to be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander (or vice versa).

Results

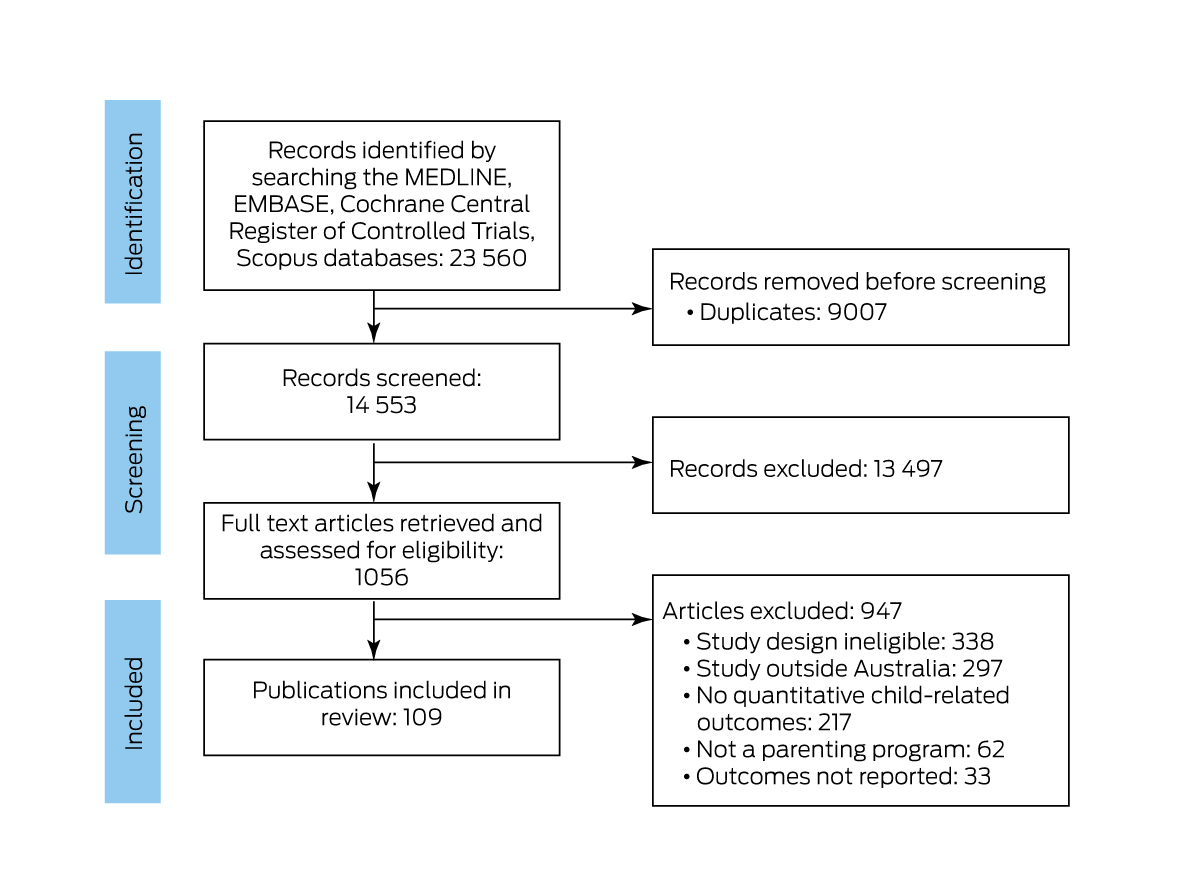

Records for 14 553 unique articles were initially screened; the full text of 1056 articles was retrieved for further assessment; 109 articles were deemed eligible for inclusion in our review (Box 1; Supporting Information, section 3). Thirty‐six studies were conducted in Queensland (33%), 33 in Victoria (30%), and 24 in New South Wales (22%); 77 studies were undertaken during 2010–2019 (71%). Sixty‐eight studies assessed mental health alone (62%) and nine the mental and physical health of children (8%). The most frequent mode of delivery was group face‐to‐face delivery (62 publications, 56%); sixty‐one studies (56%) did not directly include children in the program (Box 2).

To what extent are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents included in trials of parenting programs in Australia?

Of the 109 studies included in our review, nine RCTs12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 including 1543 participating parents reported how many participants were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander parents. These studies were conducted in NSW (three), Queensland (three), and Victoria (two), and one study was conducted across multiple states. Three studies13,14,19 reported separately whether participants identified as Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, or both. Of the 15 559 parents who participated in the 109 studies, 93 (0.6%) were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people; 51 were participants in a single study12 (Box 3). When reported, the proportion of parents who were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander were 0–3%14,15,16,17,19,20, 31%13 and 100%.12

Two publications described specific interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.12,21 One RCT involved a dental hygiene program in thirty remote Northern Territory communities; the children in the program were aged 18–47 months.21 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities were visited every six months over two years by practitioners who applied fluoride varnish to the children's teeth, provided oral health education for families, and trained primary health workers. Although it targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, it did not report specific strategies for involving Indigenous mothers or fathers.21

The second RCT involved a Positive Parenting Program (Triple P) for reducing “problem child behaviour” and “dysfunctional parenting practices”.12 The program, conducted in four Queensland health clinics over eight weeks and with follow‐up at six months, targeted Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, but not fathers specifically. The program included consultation with Indigenous people, but the publication did not provide comprehensive details about the process, and the program was not culturally tailored to the specific needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers.12

To what extent are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers involved in trials of parenting programs in Australia?

A total of 15 559 parents participated in 109 RCTs (12 046 mothers, 77.4%; 1766 fathers, 11.4%; 1747 not specified, 11.2%). No study specifically reported the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers. As the numbers of publications reporting Indigenous status and participation by fathers were both small, it was not possible to further evaluate the participation of Indigenous fathers in the parenting programs.

Do assessments of parenting programs investigate whether they are culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

Two RCTs included consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people during program development and culturally appropriate adaptation for Indigenous families, the focus of the study.12,21 The investigators planned the program content, format, and delivery to reduce potential barriers for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, but did not culturally adapt the program for Indigenous fathers. No publications listed not consulting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families as a possible study limitation (Box 3).

Discussion

We report the first scoping review of the involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families in Australian RCTs of parenting programs with quantitative child health outcomes. In light of the large literature on parenting programs we limited our review to RCTs, the findings of which often inform policy and decision making. We found that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have been engaged in such studies to only a very limited degree. Only nine of 109 relevant publications recorded the Indigenous status of participants, of 15 559 participating parents, only 93 were reported to be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people. This is concerning, as not taking the cultural background of participants into consideration may reflect a generally inadequate understanding of the social factors that influence program engagement and exclude the perspectives of specific groups. In particular, programs designed without considering factors that influence Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander engagement may exclude them from participation.7 Indigenous parents can be reluctant to seek support because a history of exclusion from services has damaged their relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.7

Despite the recognised link between parental health and child health outcomes,22 only two studies explicitly targeted Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander children,12,21,22 and none recorded not doing so as a study limitation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people face major health disparities compared with other Australians,5 but 106 of the reviewed publications on interventions for improving child physical and mental health did not consider the specific needs of Indigenous families.

Of the 109 publications reviewed, only two reported consulting Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander families during program design.12,21 This is a major problem; programs undertaken in Indigenous communities must be developed with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander interests in mind, and must explicitly meet the unique needs of these communities. Meaningful consultation requires time developing relationships with local people and empowering them to design programs relevant to their communities. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people must be involved in research from its inception and have the autonomy to define the terms and measures of program success.6

Only one study12 described an intervention adapted to the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents. Indigenous people had reviewed the program content, resources, and delivery format, and the language, images, and delivery style were modified in response to their feedback. Nevertheless, the program objectives and outcomes reflected a deficit view of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parenting; parents who received the culturally tailored program (Triple P) reported a significant drop in rates of problem child behaviour and less reliance on some dysfunctional parenting practices than families on the waiting list.12 It is critical that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parenting practices be respected and that culturally adapted programs are built on the values shared by Indigenous parents.

The number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers participating in parenting programs, and the nature of their engagement, is unknown, but, given the overall low participation rate of fathers in such programs, it is probably negligible. In the studies limited to one participating parent whose gender was reported, 11.4% of all participating parents (Indigenous and non‐Indigenous) were fathers. This is particularly concerning, given the influence that fathers have on the health and wellbeing of their own children.22 Only nine studies reported the Indigenous status of participants, and none reported Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander fathers as participants, despite their critical role in child rearing. In traditional Aboriginal parenting, a man's ability to care for children was so highly regarded that cultural authority could be earned through nurturing others.8

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers do not have adequate access to culturally appropriate parenting programs.4 Themes such as resource relevance, the healing of men, and supporting cultural needs are important considerations when culturally tailoring programs.23 Research regarding culturally appropriate programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers and their children, however, has been scarce. Successful programs must support the engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.7

Limitations

The strengths of our review include our comprehensive, broad search strategy. The lead reviewer is an Aboriginal man with extensive experience working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. As we limited our review to RCTs, our findings may not be generalisable to all parenting programs in Australia. Further, differences between parenting programs in context, objectives, and outcomes were quite large. Reporting standards have evolved, and earlier studies would not have been expected to collect data on cultural identity. However, cultural blindness clearly still affects contemporary research, as this information is still often not collected. This is a widespread problem in this field, evident even in some of the reviewed articles by members of our reviewer team. Reducing cultural bias and ensuring that researchers collect data and report on the involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is important for future research.

Conclusion

The unsatisfactory level of engagement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families in studies of parenting programs for improving the physical and mental health of children is concerning. We could not identify any RCTs in which the participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander fathers was reported, and few interventions were tailored to the cultural needs of Indigenous people. If parenting research in Australia is to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, it must include consultation with local communities, adapt interventions and research methods to the needs of the participating parents and their communities, include Indigenous people as research leaders, and improve the recruitment and retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants.

Box 1 – Identification and selection of publications for inclusion in our review (PRISMA flowchart)*

* The 109 included publications are listed in the Supporting Information, part 3.

Box 2 – Characteristics of the 109 publications on randomised controlled trials of Australian parenting programs included in our review

|

Characteristic |

Publications |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Publication year |

|

||||||||||||||

|

1990–1999 |

3 (3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

2000–2009 |

24 (22%) |

||||||||||||||

|

2010–2019 |

77 (71%) |

||||||||||||||

|

2020 |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Location of study* |

|

||||||||||||||

|

New South Wales |

24 (22%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Northern Territory |

1 (1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Queensland |

36 (33%) |

||||||||||||||

|

South Australia |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Victoria |

33 (30%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Western Australia |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Multiple states/territories |

5 (5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Program limited to one participating parent |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

75 (69%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

34 (31%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Participating parents |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Mothers |

12 046 (77.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Fathers |

1766 (11.4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Not reported |

1747 (11.2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Parent/child involvement |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Parent only |

61 (56%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Parent and child together |

38 (35%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Uncategorised |

10 (9%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Program age group |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Newborn/infant (0–1 year) |

15 (14%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Toddler (2–4 years) |

36 (33%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Child (5–9 years) |

26 (24%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Pre‐adolescent (10–12 years) |

9 (8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Adolescent (13–17 years) |

5 (4%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Not applicable |

18 (17%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Program focus |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Mental health |

68 (62%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Physical health |

30 (28%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Both mental and physical health |

9 (8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Uncategorised |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Program mode of delivery |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Face‐to‐face (multiple families) |

62 (56%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Face‐to‐face (one family) |

19 (18%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Online/device‐based |

11 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Other/distance |

6 (6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Uncategorised |

11 (10%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – The inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents in published Australian trials of parenting programs

|

Characteristic |

Number |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number of publications |

109 |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander parent participation reported |

|||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

9 (8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

100 (92%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Number of parent participants |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander |

93 (0.6%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Non‐Indigenous |

1450 (9.3%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Not reported |

14 016 (90.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander child participation reported |

|||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

9 (8%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

100 (92%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Number of child participants |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander |

763 (3.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Non‐Indigenous |

880 (4.1%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Not reported |

20 048 (92.4 %) |

||||||||||||||

|

Specifically targeted program for Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander children |

|||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

107 (98%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Consultation with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people reported |

|||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

107 (98%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Program culturally adapted for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander participants |

|||||||||||||||

|

Yes |

2 (2%) |

||||||||||||||

|

No |

107 (98%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

- Jake MacDonald1

- Myles Young2

- Briana Barclay3

- Stacey McMullen2

- James Knox2

- Philip Morgan3

- 1 Office of Indigenous Strategy and Leadership, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

- 2 The University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

- 3 Centre for Active Living and Learning, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Newcastle, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Newcastle agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Bailey EL, van der Zwan R, Phelan TW, Brooks A. The 1‐2‐3 magic program: implementation outcomes of an Australian pilot evaluation with school‐aged children. Child Fam Behav Ther 2012; 34: 53‐69.

- 2. Stevens J, Binns A, Morgan B, Egger G. Meaninglessness, alienation, and loss of culture/identity (MAL) as determinants of chronic disease. In: Egger G, Binns A, Rössner S, Sagner M, editors. Lifestyle medicine; third edition. London: Academic Press, 2017; pp. 317‐325.

- 3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey. Reference period 2018–19 financial year. 11 Dec 2019. https//www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐peoples/national‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐survey/latest‐release (viewed Sept 2023).

- 4. Canuto K, Harfield SG, Canuto KJ, Brown A. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and parenting: a scoping review. Aust J Primary Health 2019; 26: 1‐9.

- 5. Stuart G, May C, Hammond C. Engaging Aboriginal fathers. Developing Practice 2015; 42: 4‐17.

- 6. Bessarab D, Ng'andu B. Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 2010; 3: 37–51.

- 7. Reilly L, Rees SJ. Fatherhood in Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: an examination of barriers and opportunities to strengthen the male parenting role. Am J Mens Health 2018; 12: 420‐430.

- 8. Ryan F. Kanyininpa (holding): a way of nurturing children in Aboriginal Australia. Aust Social Work 2011; 64: 183‐197.

- 9. Central Australian Aboriginal Congress. Aboriginal male health summit 2008 [draft report]. 20 July 2008. https://nacchocommunique.com/wp‐content/uploads/2018/06/2008‐national‐male‐health‐summit‐of‐reports‐1‐and‐2.pdf (viewed Sept 2023).

- 10. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467‐473.

- 11. Morgan PJ, Young MD, Lloyd, AB, et al. Involvement of fathers in pediatric obesity treatment and prevention trials: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2017; 139: e20162635.

- 12. Turner KMT, Richards M, Sanders MR. Randomised clinical trial of a group parent education programme for Australian Indigenous families. J Paediatr Child Health 2007; 3: 429‐437.

- 13. Pineda J, Dadds MR. Family intervention for adolescents with suicidal behavior: a randomized controlled trial and mediation analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013; 52: 851‐862.

- 14. Hammersley ML, Okely AD, Batterham MJ, Jones RA. An internet‐based childhood obesity prevention program (Time2bHealthy) for parents of preschool‐aged children: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21: e11964.

- 15. Tonge B, Brereton A, Kiomall M, et al. A randomised group comparison controlled trial of “preschoolers with autism”: a parent education and skills training intervention for young children with autistic disorder. Autism 2014; 18: 166‐177.

- 16. Duncanson K, Burrows T, Collins C. Effect of a low‐intensity parent‐focused nutrition intervention on dietary intake of 2‐to 5‐year olds. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57: 728‐734.

- 17. Thomas R, Zimmer‐Gembeck MJ. Parent–child interaction therapy: an evidence‐based treatment for child maltreatment. Child Maltreat 2012; 17: 253‐266.

- 18. Fraser JA, Armstrong KL, Morris JP, Dadds MR. Home visiting intervention for vulnerable families with newborns: follow‐up results of a randomized controlled trial. Child Abuse Negl 2000; 24: 1399‐1429.

- 19. Hart LM, Damiano SR, Paxton SJ. Confident body, confident child: a randomized controlled trial evaluation of a parenting resource for promoting healthy body image and eating patterns in 2‐to 6‐year old children. Int J Eat Disord 2016; 49: 458‐472.

- 20. Wyse R, Wolfenden L, Campbell E, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial of a telephone‐based parent intervention to increase preschoolers’ fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 96: 102‐110.

- 21. Slade GD, Bailie RS, Roberts‐Thomson K, et al. Effect of health promotion and fluoride varnish on dental caries among Australian Aboriginal children: results from a community‐randomized controlled trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011; 39: 29‐43.

- 22. Young MD, Morgan PJ. Paternal physical activity: an important target to improve the health of fathers and their children. Am J Lifestyle Med 2017; 11: 212‐215.

- 23. Jia T. Indigenous young fathers’ support group. Aboriginal Isl Health Work J 2000; 24: 18‐20.

Abstract

Objectives: To assess the inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents in trials of parenting programs in Australia; the involvement of Indigenous fathers in such studies; and whether parenting programs are designed to be culturally appropriate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Study design: Scoping review of peer‐reviewed journal publications that report quantitative outcomes for Australian randomised control trials of parenting programs in which the participants were parents or caregivers of children under 18 years of age, and with at least one outcome related to children's health, health behaviour, or wellbeing.

Data sources: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Scopus databases.

Data synthesis: Of 109 eligible publications, nine reported how many participants were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people; three specified whether they were Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, or both. Two publications described specific interventions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children; both reported consultation with Indigenous people regarding program design. Of the 15 559 participating parents in all included publications, 93 were identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people. No publications noted as study limitations the absence of consultation with Indigenous people or the low participation rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families.

Conclusions: The specific needs and interests of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families have not generally been considered in Australian trials of parenting programs that aim to improve the mental and physical health of children. Further, Indigenous people are rarely involved in the planning and implementation of the interventions, few of which are designed to be culturally appropriate for Indigenous people. If parenting research in Australia is to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families, it must include consultation with local communities, adapt interventions and research methods to the needs of the participating parents and their communities, and improve the recruitment and retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants.