Voluntary assisted dying is now lawful in all Australian states, with territories likely to follow.1 As this new end‐of‐life choice becomes more widely available and known, we should anticipate it arising during end‐of‐life care discussions with patients. In Australia, unlike some international models,2,3 voluntary assisted dying is not available to people without decision‐making capacity. Therefore, patients cannot request voluntary assisted dying through an advance care directive or other advance care planning document. However, some competent adult patients undertaking advance care planning may want to discuss voluntary assisted dying. Reflection is needed to prepare patients, clinicians and health services for discussions about voluntary assisted dying during advance care planning.

Advance care planning is conceptually different from voluntary assisted dying

As voluntary assisted dying was being debated and legalised across Australia, efforts were made to distinguish it from advance care planning.4 This conceptual work is important because the implementation of voluntary assisted dying is often accompanied by confusion and anxiety,5,6 and the two concepts are often misunderstood and conflated.7 We support educative efforts that define and distinguish voluntary assisted dying and advance care planning because this clarity enables patients to make informed choices.

Advance care planning is a “process of planning for future health and personal care whereby the person's values, beliefs and preferences are made known to guide decision‐making at a future time when that person cannot make or communicate their decisions.”8 By contrast, in Australia, voluntary assisted dying provides assistance to die for adults with decision‐making capacity who meet strict eligibility criteria, for example, if the patient is expected to die within 6 or 12 months from an advanced, progressive medical condition.1

A critical difference is that voluntary assisted dying in Australia is available only to adults with decision‐making capacity, while advance care planning focuses on decision making about future care at a time when capacity is lost. Because access to voluntary assisted dying requires a person to retain decision‐making capacity throughout the process, advance requests for voluntary assisted dying cannot be given in an advance care directive (or any other advance care planning document). Nor can a person's substitute decision maker seek voluntary assisted dying on the person's behalf. This distinction is clearly reflected in law (indeed, some medical decision‐making legislation expressly excludes voluntary assisted dying) and guidance across Australia.9,10,11,12,13

Advance care planning practices and systems need to recognise voluntary assisted dying

Although voluntary assisted dying is not the focus of advance care planning, clinicians and health services undertaking advance care planning need to be prepared for this topic. A pragmatic reason is voluntary assisted dying will inevitably be raised by some patients in their end‐of‐life planning. Attempts to exclude voluntary assisted dying are impractical as patients see end‐of‐life choices holistically and are unlikely to partition advance care planning and voluntary assisted dying.

An ethical reason to prepare for voluntary assisted dying discussions during advance care planning is it may sometimes be appropriate to inform patients about their potential or future eligibility for voluntary assisted dying.14,15 Some patients, as with end‐of‐life discussions generally,7 may be waiting for health practitioners to initiate voluntary assisted dying discussions. Other patients may not be aware of voluntary assisted dying or their potential eligibility.

Where it is legally possible to raise voluntary assisted dying (Box 1) and clinically appropriate, informing patients of all possible end‐of‐life choices would facilitate decisions that align with the values, beliefs and preferences at the heart of advance care planning. We emphasise this must be done sensitively, within the law, and guided by good clinical practice about end‐of‐life care discussions.18

Three critical issues for advance care planning systems and practices to consider

Restrictions on raising voluntary assisted dying

If a patient raises voluntary assisted dying during an advance care planning discussion, health practitioners are free to discuss it. However, if not initiated by a patient, Australian law (Box 1) is unusual internationally because it regulates whether, and how, a health practitioner can raise voluntary assisted dying with a patient.

In Victoria and South Australia, law prohibits registered health practitioners from raising voluntary assisted dying with a patient or initiating a discussion about it. No other lawful health care option is prohibited from being raised in this way.19 Victorian doctors and family caregivers have reported confusion and access barriers as a result of this restriction.20,21 Advance care planning programs in these states should ensure health practitioners are aware of this legal duty but make it clear that voluntary assisted dying can be discussed once raised by a patient. This includes understanding when voluntary assisted dying has been raised, given reports that patients struggle to know the “right words”21 to successfully raise this topic, and the need for open questions to facilitate a lawful discussion.

In all other states, doctors can raise voluntary assisted dying, as can some or all other health practitioners, depending on the state, but this is subject to providing certain information at the same time (Box 1).1 Again, advance care planning programs in these jurisdictions need to ensure their practitioners understand these laws.

Individual conscience and institutional objection

Advance care planning programs must address conscientious objection, which is legally protected. Some opposed health practitioners may be willing to engage in advance care planning discussions that include voluntary assisted dying, but others may not.22 However, objecting practitioners must still be aware of potential legal duties. For example, voluntary assisted dying laws in some states require that patients making a first formal request for voluntary assisted dying be provided specific information about it, including about practitioners or voluntary assisted dying services (Box 2). Professional and ethical duties imposed by bodies such as the Medical Board of Australia and the Australian Medical Association also include not hindering access to voluntary assisted dying.23,24

Institutions objecting to voluntary assisted dying can also affect advance care planning. While institutions may object to a range of practices,25,26 relevant here is an objecting institution whose advance care planning program does not permit discussion of voluntary assisted dying. Complex laws about institutional objection to voluntary assisted dying exist in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia1 and can affect implementation of local advance care planning programs.

Accessing voluntary assisted dying requires planning and time

If advance care planning discussions do include voluntary assisted dying, they should ensure patients know that accessing voluntary assisted dying takes time, and requires planning20,21 (although it can be expedited in urgent cases).1 The most recent Victorian Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board report advises voluntary assisted dying is not an emergency procedure, with a median time from first request to dispensing medication of 34 days (interquartile range, 23–53 days).27 This need to plan arises from: the time needed for the rigorous assessment and approval process; eligibility criteria that mean a person is expected to die within 6 or 12 months, and so is on a trajectory to death and reduced physical (and potentially mental) capacity; and the possibility of voluntary assisted dying requests being made late in a person's illness.21

Preparing advance care planning programs and practices for voluntary assisted dying

Voluntary assisted dying will increasingly arise in advance care planning discussions now that it is legal in all Australian states. The palliative care sector has been proactive in addressing voluntary assisted dying in end‐of‐life discussions, with Palliative Care Australia, Australia's peak palliative care body, developing a position statement and guiding principles to support people providing care for individuals with a life‐limiting condition who may wish to access voluntary assisted dying. These principles state that individuals and their families and carers “must be treated with dignity and respect and supported to explore options available to them, which may include [voluntary assisted dying]”.28

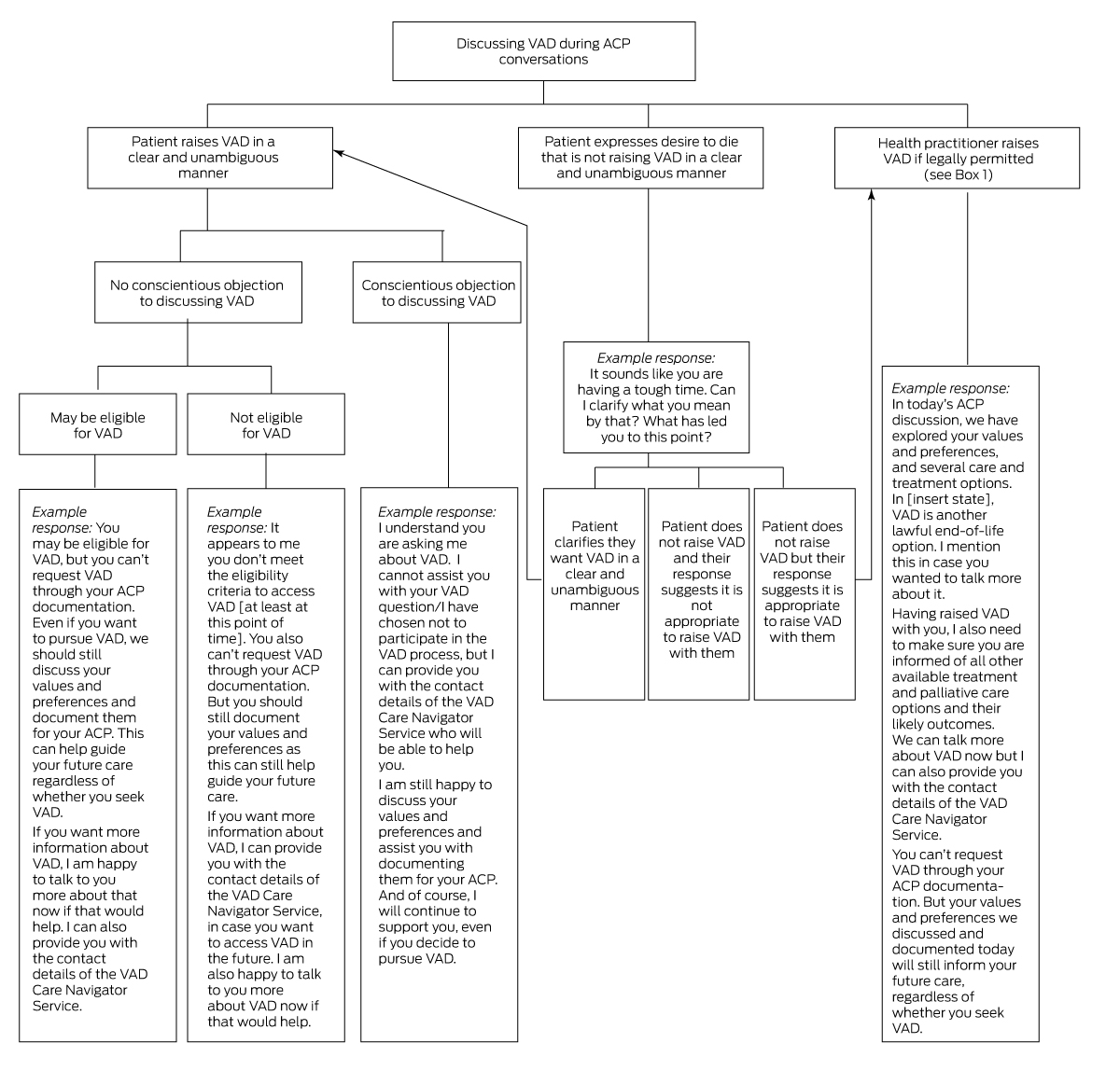

Advance care planning programs, policies and practices must also explicitly recognise the impact of voluntary assisted dying, including addressing the three issues outlined above. Much of the work to date has focused on differentiating advance care planning and voluntary assisted dying. This is important, but efforts must now extend to support optimal advance care planning in the context of new voluntary assisted dying laws. This requires health systems and advance care planning programs to adapt advance care planning policies, guidelines and information to engage with how voluntary assisted dying will be discussed in advance care planning conversations (see Box 3 for a framework for such conversations).

Health practitioners undertaking advance care planning should receive training on the impact of voluntary assisted dying on these discussions. Conversation guides can also help navigate lawful and patient‐centred advance care planning discussions that include voluntary assisted dying where appropriate. Processes for health practitioners to access support or escalate for advice are also needed. These responses should harness existing voluntary assisted dying resources and services where possible, such as health department voluntary assisted dying guidance and voluntary assisted dying care navigators in each state (Box 4).

Advance care planning is centred on respecting a person's values, beliefs and preferences, which may now include a choice for voluntary assisted dying. Existing approaches to advance care planning must adapt to reflect this, requiring thoughtful engagement at the system, program, and practitioner level.

Box 1 – Permissibility of registered health practitioners initiating discussions about voluntary assisted dying in Australia*

|

|

New South Wales |

Queensland |

South Australia |

Tasmania |

Victoria |

Western Australia |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Doctors |

Yes, provided they inform at same time of available treatment and palliative care options and their likely outcomes |

Yes, provided they inform at same time of available treatment and palliative care options and their likely outcomes |

No |

Yes, provided they inform at same time of available treatment and palliative care options and their likely outcomes |

No |

Yes, provided they inform at same time of available treatment and palliative care options and their likely outcomes |

|||||||||

|

Nurse practitioners |

Yes, provided they inform at same time that palliative care and treatment options are available, and that the patient should discuss these with their doctor |

As above |

No |

Yes, provided they inform during discussion that a doctor would be the most appropriate person with whom to discuss the VAD process and care and treatment options |

No |

As above |

|||||||||

|

Other registered health practitioners |

As for nurse practitioners |

No |

No |

As for nurse practitioners |

No |

No |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Note: Some voluntary assisted dying legislation also regulates the conduct of discussions by health care workers. Table adapted from Waller et al,1 Voluntary assisted dying in aged care: roles and obligations of medical practitioners,16 and Voluntary assisted dying in aged care: roles and obligations of registered nurses.17 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Doctors’ conscientious objection obligations to patients who make a first request* for voluntary assisted dying

|

|

New South Wales |

Queensland |

South Australia |

Tasmania |

Victoria |

Western Australia |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Provision of information |

– |

Contact details of a medical practitioner or service who can assist or the details of the care navigator service |

– |

Information sheet about voluntary assisted dying, and contact details of the Voluntary Assisted Dying Commission |

– |

Information sheet about voluntary assisted dying |

|||||||||

|

Timeframe to notify the patient of refusal of first request |

Immediately |

Immediately |

Within 7 days |

Within 7 days (plus 48 hours to decide) |

Within 7 days |

Immediately |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* A first request is a formal part of the voluntary assisted dying request and assessment process where a patient makes a clear request to a doctor for voluntary assisted dying. Table adapted from Waller et al1 and Voluntary assisted dying in aged care: roles and obligations of medical practitioners.16 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Selection of voluntary assisted dying health practitioner guidance relevant for advance care planning

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Waller K, Del Villar K, Willmott L, White B. Voluntary assisted dying in Australia: a comparative and critical analysis of state laws. Univ NSW Law J 2023; 46: 1663‐1700.

- 2. De Vleminck A, Pardon K, Houttekier D, et al. The prevalence in the general population of advance directives on euthanasia and discussion of end‐of‐life wishes: a nationwide survey. BMC Palliat Care 2015; 14: 71.

- 3. Mevis P, Postma L, Habets M, et al. Advance directives requesting euthanasia in the Netherlands: do they enable euthanasia for patients who lack mental capacity. J Med Law Ethics 2016; 4: 127‐140.

- 4. Advance Care Planning Australia. The role of advance care planning in the context of voluntary assisted dying. 19 Sept 2023. https://qhscb.squiz.cloud/advancecare/about‐us/news/the‐role‐of‐advance‐care‐planning‐in‐the‐context‐of‐voluntary‐assisted‐dying (viewed Nov 2023).

- 5. Rutherford J, Willmott L, White B. Physician attitudes to voluntary assisted dying: a scoping review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021; 11: 200‐208.

- 6. Byrnes E, Ross A, Murphy M. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to implementing assisted dying: a qualitative evidence synthesis of professionals’ perspectives. Omega 2022; https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221116697 [Epub ahead of print].

- 7. Scott IA, Mitchell GK, Reymond EJ, Daly MP. Difficult but necessary conversations — the case for advance care planning. Med J Aust 2013; 199: 662‐666. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2013/199/10/difficult‐necessary‐conversations‐case‐advance‐care‐planning

- 8. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National framework for advance care planning documents. May 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐framework‐for‐advance‐care‐planning‐documents?language=en (viewed Aug 2023)

- 9. Medical Treatment Planning and Decisions Act 2016 (Vic).

- 10. Advance Care Directives Act 2013 (SA).

- 11. Powers of Attorney Act 1998 (Qld).

- 12. Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2021 (NSW).

- 13. Department of Health (Tasmania). Voluntary assisted dying in Tasmania. Fact sheet: information for medical practitioners. Version 1.0. https://www.health.tas.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022‐11/fact_sheet_information_for_medical_practitioners.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 14. Buchbinder M. Aid‐in‐dying laws and the physician's duty to inform. J Med Ethics 2017; 43: 666‐669.

- 15. Zhou YMJ, Shelton W. Physicians’ end of life discussions with patients: is there an ethical obligation to discuss aid in dying? HEC Forum 2020; 32: 227‐238.

- 16. End of Life Directions for Aged Care. Voluntary assisted dying in aged care: roles and obligations of medical practitioners. Brisbane: ELDAC, 2023. https://www.eldac.com.au/Portals/12/Documents/Factsheet/Legal/VAD‐aged‐care‐medical‐practitioners.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 17. End of Life Directions for Aged Care. Voluntary assisted dying in aged care: roles and obligations of registered nurses. Brisbane: ELDAC, 2023. https://www.eldac.com.au/Portals/12/Documents/Factsheet/Legal/VAD‐aged‐care‐registered‐nurses.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 18. Brassfield ER, Buchbinder M. Clinical discussion of Medical Aid‐in‐Dying: minimizing harms and ensuring informed choice. Patient Educ Couns 2020; 104: 671‐674.

- 19. White B, Del Villar K, Close E, Willmott L. Does the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 (Vic) reflect its stated policy goals? Univ NSW Law J 2020; 43: 417‐451.

- 20. Willmott L, White BP, Sellars M, Yates PM. Participating doctors’ perspectives on the regulation of voluntary assisted dying in Victoria: a qualitative study. Med J Aust 2021; 215: 125‐129. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/215/3/participating‐doctors‐perspectives‐regulation‐voluntary‐assisted‐dying‐victoria

- 21. White BP, Jeanneret R, Close E, Willmott L. Access to voluntary assisted dying in Victoria: a qualitative study of family caregivers’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators. Med J Aust 2023; 219: 211‐217. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2023/219/5/access‐voluntary‐assisted‐dying‐victoria‐qualitative‐study‐family‐caregivers

- 22. Haining CM, Keogh LA. “I haven't had to bare my soul but now I kind of have to”: describing how voluntary assisted dying conscientious objectors anticipated approaching conversations with patients in Victoria, Australia. BMC Med Ethics 2021; 22: 149.

- 23. Medical Board of Australia, Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. Good medical practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia. Oct 2020. https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/Codes‐Guidelines‐Policies/Code‐of‐conduct.aspx (viewed Aug 2023).

- 24. Australian Medical Association. AMA code of ethics 2004. Editorially revised 2006. Revised 2016. https://www.ama.com.au/sites/default/files/2021‐02/AMA_Code_of_Ethics_2004._Editorially_Revised_2006._Revised_2016_0.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 25. White BP, Jeanneret R, Close E, Willmott L. The impact on patients of objections by institutions to assisted dying: a qualitative study of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMC Med Ethics 2023; 24: 22.

- 26. White BP, Willmott L, Close E, Downie J. Legislative options to address institutional objections to voluntary assisted dying in Australia. Univ NSW Law J Forum 2021: (3): 1‐19.

- 27. Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board. Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board annual report (July 2022–June 2023). Melbourne: Safer Care Victoria, 2023. https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/reports‐and‐publications/voluntary‐assisted‐dying‐review‐board‐annual‐report‐july‐2022‐to‐june‐2023 (viewed Sept 2023).

- 28. Palliative Care Australia. Voluntary assisted dying in Australia: guiding principles for those providing care to people living with a life‐limiting illness. Canberra: Palliative Care Australia, 2022. https://palliativecare.org.au/statement/voluntary‐assisted‐dying‐in‐australia‐guiding‐principles‐for‐those‐providing‐care‐to‐people‐living‐with‐a‐life‐limiting‐illness‐2/ (viewed Aug 2023).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Queensland University of Technology, as part of the Wiley ‐ Queensland University of Technology agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This research is funded by the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT190100410: Enhancing end‐of‐life decision‐making: optimal regulation of voluntary assisted dying). We acknowledge the research assistance provided by Annabelle Milina (Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Queensland University of Technology).

Ben P White and Lindy Willmott were engaged by the Victorian, Western Australian and Queensland governments to provide the legislatively required training for doctors (and nurses and nurse practitioners where relevant) involved in voluntary assisted dying. Ben P White and Lindy Willmott have been engaged by the Western Australian Government to be involved in the statutory review of the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2019 (WA). Lindy Willmott is also a member of the Queensland Voluntary Assisted Dying Review Board. Madeleine Archer was employed on the Victorian, Western Australian and Queensland voluntary assisted dying training projects. Casey M Haining was employed on the Queensland voluntary assisted dying training project as a legal writer and as a research fellow on the statutory review of the Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2019 (WA). Casey M Haining is Advance Care Planning Australia's former National Policy Manager; views expressed in this article represent her own views and do not necessarily reflect those of Advance Care Planning Australia.