First Nations peoples have inhabited Australia for at least 65 000 years.1 First Nations Australians have displayed strength and resilience in the face of the ongoing colonisation of Australia, fragmented communities, and loss of culture, language and connection to Country. The resultant social injustices continue to affect the determinants of health, leading to subsequent chronic disease.2,3 Compared with non‐Indigenous Australians, First Nations Australians currently experience lower incomes, lower education attainment, lower rates of home ownership, and higher rates of unemployment and imprisonment.4

The incidence, prevalence and burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in First Nations Australians is one of the highest in the world, which is reflective of the social gradient of disadvantage.5,6,7,8 First Nations Australians experience two times higher CKD prevalence9 and eight to nine times higher rates of kidney replacement therapy than the non‐Indigenous Australian population.10 These disparities demonstrate the impacts of social disadvantage without evidence of genetic predisposition. Addressing the social determinants of health to achieve equity has been emphasised by the World Health Organization3 and underpins chronic disease prevention. It has been recognised that Closing the Gap, which aimed to improve First Nations Australians’ life expectancy, has failed to address the determinants of health that affect individuals’ health and wellbeing.11,12 Consequently, the 2020 Closing the Gap report recommended a true partnership with First Nations Australian communities be formed when codesigning policies and programs to ensure that community needs are met.13 These clinical practice guidelines are the first to be developed in partnership with First Nations Australians to improve kidney health and wellbeing. The full version of the guidelines is available at www.cariguidelines.org/home/management‐of‐chronic‐kidney‐disease‐among‐first‐nations.

Guideline scope

These guidelines aim to address the problems faced by First Nations Australians living with CKD identified through community consultations14,15,16,17 and the need for recommendations identified by clinical experts.18 Recommendations and ungraded statements are directed towards improving clinicians’ understanding of the clinical care desired by First Nations Australians and aim to improve the equity of the management of CKD.

Methods

These guidelines adhered to international best practice for guideline development,19,20 including using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II checklist21 assessment is available in the Supporting Information. The guidelines development methods are available online in Appendix A of the full guidelines.

Community consultation

Every which way you look at renal disease in Aboriginal people, the only solutions that will work in the long term are those that are Aboriginal‐led, culturally responsive, located in Aboriginal organisations and evaluated through an Aboriginal lens. (Pat Turner CEO, National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organizations, National Indigenous Dialysis and Transplantation Conference, Alice Springs, Northern Territory, 2019)22

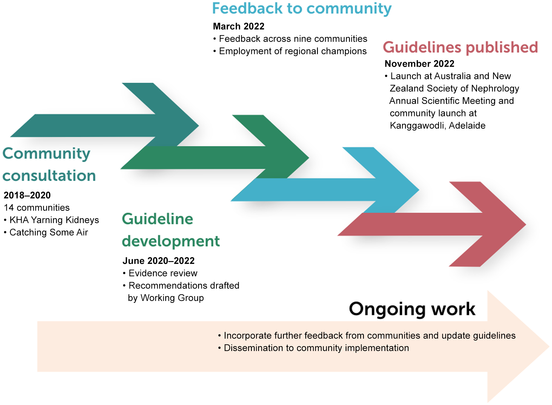

The broad and purposive community feedback and priority setting for these guidelines occurred during the Kidney Health Australia Yarning Kidneys,14 which included consultations led by Aboriginal Kidney Care Together – Improving Outcomes Now (AKction)16,17 and Catching Some Air.15 A partnership approach was adopted, with a panel of clinicians involved in the care of First Nations Australians with CKD; targeted site engagement with First Nations Australian communities and services across urban, regional and remote communities; and additional consultation and feedback from national peak First Nations organisations.23 The 14 community consultations identified the priorities of First Nations Australians with lived experience of CKD, which informed the scope, and provided evidence to supplement studies for the development of guideline recommendations.14,15,16,17 Planned ongoing engagement and consultation with targeted First Nations Australian communities throughout the guideline development were interrupted by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. To overcome these challenges, group yarning sessions occurred during 2022 with community groups or, when appropriate, with local champions. The draft guideline recommendations were reviewed by 11 communities involved in the previous consultations and were consulted along with one additional consultation with another community (Box 1). The Guidelines Working Group also included First Nations peoples with lived experience of kidney disease, who provided important insights for the development of the guidelines and also informed the development of the Flow and thrive artwork (Box 2). All feedback was considered and the guidelines were updated accordingly (Box 3).

Evidence synthesis

Traditionally, clinical practice guidelines are developed with a Western biomedical view of health and have not incorporated First Nations Australian perspectives on health or health research methods, such as “yarnings”. These guidelines have extended the traditional model by including the targeted community consultation findings in the rationale for recommendations. Priorities and topics identified by the communities during the Catching Some Air15 and Kidney Health Australia Yarning Kidneys14,17 consultations were transformed into focused research questions using the population intervention/exposure comparator outcome (PICO and PECO) methodology format to enable a comprehensive literature search (Appendix A in the full guidelines). There has been limited inclusion of First Nations Australians in the research priority setting of the kidney health community. As a result, we approached research questions broadly and included all study types, except for case studies and editorials, in our systematic review.

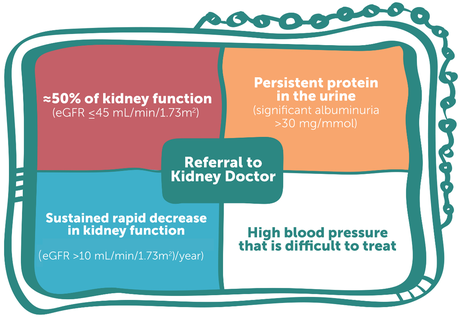

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet in May 2022 (Appendix B in the full guidelines). Overall, we identified 8236 citations and included 200 reports to inform the development of these guidelines (Box 4).

The included studies were identified, abstracted, synthesised and appraised by two independent reviewers and approved by the Working Group. The characteristics of the included studies were summarised descriptively (Appendix C in the full guidelines), and findings across studies were combined using a mixed‐method synthesis approach.24 The certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach for interventions and exposures25 and GRADE CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research) for qualitative findings.26 The tables with the summary of findings were developed (Supporting Information and Appendix D in the full guidelines) and considered by the Guidelines Working Group, with expertise across First Nations health, clinical nephrology, nursing, lived experience of CKD, health economics, clinical research, guideline methodology and cultural safety. The guideline of the GRADE Evidence to Decision Framework was adapted to include the First Nations voice, with the “four Cs” of community voice: clinical evidence; cultural considerations; and cost, capacity, equity and other considerations (Box 5). The findings from the community consultations and feedback undertaken for these guidelines were considered under the “community voice” domain of the Evidence to Decision Framework.

The rationale underpinning the grading and strength of the recommendations is provided in Box 6 and Box 7. The guidelines underwent peer review by experts in nephrology, First Nations health practitioners, people with lived experience of CKD, and peak First Nations organisations who were invited to provide feedback. Yarnings with First Nations communities involved in the initial community consultations and people with lived experience of CKD also provided feedback on the guidelines.

Main recommendations

Cultural safety and responsive kidney health care

Targeted community consultations14,15,16,17 identified that institutional racism continues to be experienced by First Nations Australians throughout the management of their CKD. These consultations highlighted that the provision of holistic care beyond the Western medical approach to health care is fundamental to the health of First Nations Australians living with CKD. First Nations Australians described the holistic care, including social and cultural aspects of care and involvement of family and other First Nations Australians, as integral to their overall wellbeing. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of CKD have rarely focused on psychosocial aspects of care27,28 and, to our knowledge, have never addressed institutional racism. In recognition of the importance and impact of racism on the provision of care, the first recommendations focused on institutional racism and on providing clinical and culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations Australians. Despite the imperative of the issues identified by the community, although there are limited studies, those published have shown that interventions focused on addressing institutional racism improved cultural safety and resulted in improved access, increased self‐agency, and involvement in shared decision making among First Nations Australians29,30,31,32,33 (Supporting Information, tables A1 and A2, and Appendices C and D in the full guidelines). The inequalities of CKD largely result from the disproportionate impact of the social determinants of health among First Nations Australians,6,8,34,35,36 with very few associations of genetic alleles with CKD burden described in First Nations Australians.36 As a result, the Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines Working Group has recommended that “Indigenous status” is removed as a factor associated with CKD. The intention is to educate and place the focus on the impact of social disadvantage and to mitigate the bias and prejudice experienced by First Nations Australians, as described throughout the community consultations.14,15,16,17

Inequity and institutional racism in health care

We recommend that health services evaluate, monitor and act upon the institutional racism within their system by addressing all domains identified in the Matrix for identifying, measuring and monitoring institutional racism within public hospitals and health services37 (Strong recommendation). Furthermore, we recommend that First Nations Reference Groups should be incorporated in kidney health services within Australia (Strong recommendation). We also recommend removing Indigenous status as a risk factor for CKD because the increased risk is explained by adverse social determinants of health, which leads to a greater burden and progression of CKD (Strong recommendation).

Cultural safety

We recommend that health care staff receive effective and responsive cultural safety training, and that continuous quality improvement strategies are undertaken to address institutional racism, using tools such as the Matrix for identifying, measuring and monitoring institutional racism within public hospitals and health services (Strong recommendation).37

Family‐ and community‐centred engagement and involvement in managing CKD

We recommend that the family and community of First Nations Australians with CKD are actively involved in all clinical appointments, according to individual preferences (Strong recommendation).

Transport and accommodation services for First Nations Australians

We recommend that health services develop clear pathways for ensuring transport and accommodation needs are prioritised and made available to patients and their family members for all health care interactions (Strong recommendation).

First Nations kidney health workforce

We recommend that health services aim to develop professional support for First Nations Australians with CKD according to their needs (Strong recommendation): First Nations nurses, allied health professionals, and doctors; Aboriginal Health Practitioners and/or Aboriginal Health Liaison Officers; patient preceptors/navigators; and interpreters.

Screening, and referral of CKD

Early targeted screening is an important and cost‐effective strategy to prevent the occurrence and progression of CKD and reduce cardiovascular disease.38,39 Concerted efforts to decrease late referrals (less than three months between referral and the commencement of kidney replacement therapy) among First Nations Australians have led to improvements in earlier engagement with specialists’ services.40 The guidelines indicate that “Indigenous status” is not an independent factor associated with CKD, the Working Group recommends earlier screening and referral criteria for First Nations Australians. This recommendation is in response to the substantially higher incidence, more rapid progression, and excess burden of disease,9,10 and the findings from the community consultations.14,15,16,17

Identification of factors associated with CKD in First Nations Australians

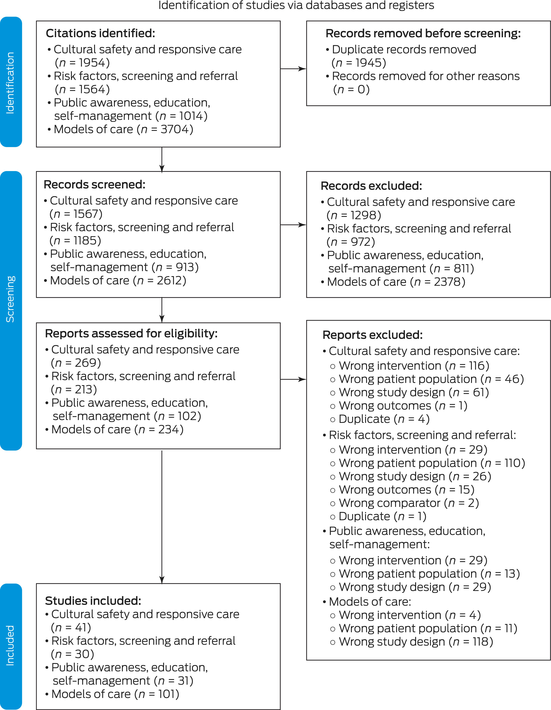

The ungraded statements highlight that an individual's susceptibility to CKD (Box 8) is increased by the following factors: family history of CKD, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, established cardiovascular disease, history of acute kidney injury, and cigarette smoking. Additional considerations include history of low birthweight, history of recurrent childhood infections, remoteness, low socio‐economic status, housing insecurity and overcrowding, education levels, and other impacts of colonisation.

Screening and early detection programs for CKD among First Nations Australians

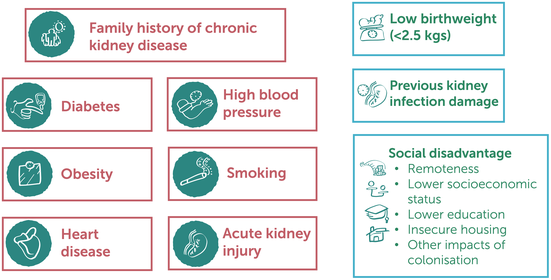

We recommend that First Nations Australians receive age‐appropriate health assessments to screen for CKD at least annually, including using the specific Medicare item number for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples health assessment (Box 9) (Strong recommendation).

Referral practices for First Nations Australians with CKD

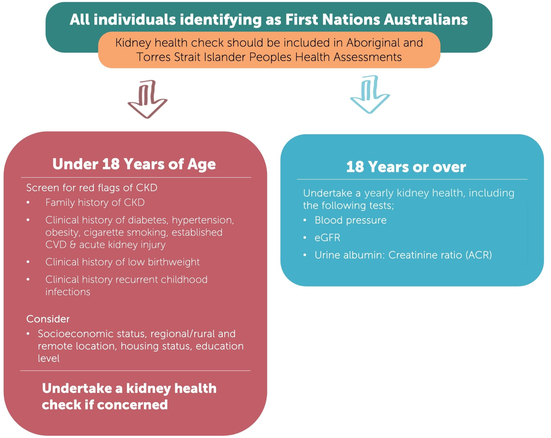

We suggest that referrals of First Nations Australians with CKD to nephrologists (or specialist‐supported kidney health teams) should be done using one or more of the following criteria (Box 10) (Conditional recommendation):

- eGFR ≤ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2;

- persistent significant albuminuria > 30 mg/mmol;

- a sustained decrease in eGFR > 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year; and

- elevated blood pressure that is not within the target range despite the use of at least three antihypertensive agents.

Public awareness, education and self‐management

Targeted community consultations emphasised the need for greater awareness and education to prevent and manage CKD. There was a desire for further engagement of local communities to deliver tailored community‐based awareness and education. Supporting First Nations Australians to self‐manage their disease, including incorporating local bush tucker, bush medicine, and other cultural activities was also a priority.14,15,16,17 Despite the limited published scientific evidence, these guidelines provide recommendations focused on increased community ownership and incorporation of First Nations culture and activities within CKD education and self‐management initiatives. The guideline recommendations and ungraded statements for this section are summarised in Box 11.

Models of care

A higher proportion of First Nations Australians live in rural and remote locations compared with non‐Indigenous Australians.42 Therefore, the management of CKD in First Nations Australians often requires extensive travel and potential relocation for extended periods, particularly for kidney replacement therapy.43 Relocation for treatment significantly affects people with CKD and their families,44,45 including high out‐of‐pocket expenses and dislocation from family, community, culture and Country.14,15,16,17 These guidelines provide recommendations on the structure and components of how care should be delivered for First Nations Australians with CKD, with a focus on keeping people on Country where possible. Recommendations for the models of care for transplantation will be updated with the completion of studies such as the National Indigenous Kidney Transplant Taskforce46,47,48 and Return to Country.49

Models of care in CKD (pre‐dialysis)

We recommend the development of dedicated programs specific for First Nations Australians to identify people at risk and diagnose and manage CKD (Strong recommendation).

We recommend that these programs (Strong recommendation):

- are codesigned and governed by First Nations communities and embedded into existing chronic disease programs;

- are adapted to ensure they are culturally safe, tailored to the community and flexible to the changing needs of the community; and

- explicitly identify and address barriers to care, including (but not limited to) institutional racism, cultural barriers, social and/or geographical barriers, transportation and/or other costs of health care to patients and families.

We suggest that programs of care (Conditional recommendation):

- be conducted within community‐controlled health services;

- use a multidisciplinary approach, with program‐specific health care workers dedicated to facilitating these programs;

- promote a culturally safe workplace culture with built‐in support for the multidisciplinary team, including (but not limited to) the provision of continuing education programs, case management workshops, clinic guidelines/protocols, and online educational materials;

- incorporate patient education and training within the program to increase patient and community empowerment; and

- use an integrated care approach when specialised nephrology services are required as part of a patient's management, including the use of telehealth services where appropriate.

Models of care in kidney failure

We recommend that health services work in partnership with Aboriginal community‐controlled health organisations to establish community‐controlled models of care that address local needs and conditions. This will allow First Nations Australians to have nurse‐supported and/or Aboriginal Health Practitioner‐supported dialysis on Country, particularly in remote areas (Strong recommendation). Furthermore, we recommend that kidney health services incorporate dialysis services (eg, mobile dialysis) to facilitate patients to have dialysis in locations where it is not otherwise available. This service should include adequate transport, accommodation, and workforce support to ensure equity (Strong recommendation).

We recommend the availability of First Nations Australians‐specific and codesigned programs to address the social and emotional wellbeing of people undergoing kidney replacement therapy (Strong recommendation). We suggest supported home dialysis models, such as community‐based home dialysis, to allow First Nations Australians to access the benefits of home dialysis (Conditional recommendation).

We recommend that kidney health services use telehealth/video link models to augment face‐to‐face care for those living and receiving dialysis in regional and remote areas (Strong recommendation). Box 11 lists other guideline recommendations not detailed in the guideline summary.

Suggestions for future research

Future research should be led by and in partnership with First Nations Australian communities and to the standards set out in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool50 and reported to the standards of the Consolidated Criteria for Strengthening the Reporting of Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples (CONSIDER) Statement.51 Undertaking true collaborative approaches will ensure that research is directed on the communities’ priorities and conducted correctly. For example, future research priorities from the CARI Guidelines Working Group include evaluating patient preceptor programs in CKD care for First Nations Australians and further evaluating nurse‐supported dialysis models of care within communities.

Conclusions

These clinical practice guidelines represent a major first step in addressing the evident disparity in CKD among First Nations Australians compared with non‐Indigenous people in Australia9,10 and improve cultural safety in health systems. Importantly, the guidelines have been developed in partnership with First Nations Australians, prioritising the Community Voice, and provide opportunity for the crucial next step of implementation.

We have done talking, it is time to implement, to change, let's do it now. (Kelli Owen, CARI First Nations Australians CKD Guidelines Launch, 16 October 2022, Sydney, New South Wales).52

Ensuring that the guidelines are drivers of equity in the health system will require ongoing partnership with First Nations communities. The evaluation of these guidelines needs to be led by First Nations Australians as well as providing transparent accountability in their implementation across nephrology units in Australia.

Box 1 – Location and details of targeted community consultations and feedback that occurred during the guidelines development

CARI = Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment.

Box 2 – Flow and thrive represents the landscape of living with a kidney condition*

* The design represents the different stages of the health journey. At times the waters are murky and turbulent, which is represented by the tsunami on the top right of the design and the mangroves to the top left. The mangroves represent the challenges of patients moving through their varying journeys, which traverse through the rivers and into calmer seas. From the right bottom hand corner of the design, a sunrise emerges, symbolising the strength and resilience of those living with kidney conditions. This design reinforces the idea that those on this journey are never alone. The boats within the river represent the family, friends, community, and support networks that surround the patients on their wellness journey. To the far left of the design is a series of lines, which represent the various medical practitioners and clinical support personnel who guide and support the patient with their ongoing expertise and care. Image reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22

Box 4 – Adapted PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses) 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews that included searches of databases and registers only

Duplicate records were identified and considered across guideline chapters. Image reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22

Box 5 – “Four Cs” framework informing guideline recommendations

|

Domain |

Description |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Community voice |

The priorities and knowledge of the First Nations Australian communities, as identified in the Catching Some Air and Kidney Health Australia Yarning Kidneys community consultations. |

||||||||||||||

|

Clinical evidence |

Balance of benefits and harms from the identified scientific literature from the formal systematic review undertaken for these guidelines, as well as findings from other important articles, reports, policies and documents identified outside of the systematic reviews scope. The certainty of the evidence was assessed using validated risk of bias tools and assessed using the GRADE approach according to study type (ie, quantitative, qualitative, or a combination of both).25,26 |

||||||||||||||

|

Cultural considerations |

Other important cultural phenomenon relevant to First Nations Australians that may have not been raised explicitly in the community consultation process. |

||||||||||||||

|

Cost, capacity, equity and other considerations |

The cost to the individual, the health systems, the health workforce (including the First Nations Australians health workforce) was considered. Implications of the recommendations on equity, including gender, remoteness and other markers of low socio‐economic status, were considered. Finally, the feasibility of the implementation of the guideline recommendations was included. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

GRADE = Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation. Table reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Final grade for overall certainty of evidence*

|

Overall evidence grade |

Description |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

High |

We are confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. |

||||||||||||||

|

Moderate |

The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. |

||||||||||||||

|

Low |

The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

||||||||||||||

|

Very low |

The estimate of effect is very uncertain and often will be far from the truth. |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

*Adapted from the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group (www.gradeworkinggroup.org). Table adapted from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 7 – Nomenclature and description for grading recommendations

|

Grade |

Implications |

||||||||||||||

|

Patients |

Clinicians |

Policy |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Strong recommendation: “we recommend” |

Most people in your situation would want the recommended course of action and only a small proportion would not. |

Most patients should receive the recommended course of action. |

The recommendation can be adopted as a policy in most situations. |

||||||||||||

|

Conditional recommendation: “we suggest” |

The majority of people in your situation would want the recommended course of action, but many would not. |

Different choices will be appropriate for different patients. Each patient needs help to arrive at a management decision consistent with their values and preferences. |

The recommendation is likely to require debate and involvement of stakeholders before policy can be determined. |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Table reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 8 – Factors associated with chronic kidney disease among First Nations Australians

Image reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22

Box 9 – Chronic kidney disease (CKD) screening matrix for First Nations Australians

CVD = cardiovascular disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. Image reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22

Box 10 – Referral matrix for First Nations Australians

eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate. Image reproduced from Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines.22

Box 11 – Additional recommendations and ungraded statements for Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among First Nations Australians22

|

Guideline chapter |

Recommendations and ungraded statement |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Cultural safety and responsive kidney health care |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Inequity and institutional racism in health care |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Cultural safety |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Family and community centred engagement and involvement in managing CKD |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Transport and accommodation services for First Nations Australians |

|

||||||||||||||

|

First Nations health workforce |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Screening, and referral of CKD |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Identification of factors associated with CKD progression in First Nations Australians |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Screening and early detection programs for CKD among First Nations Australians |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Referral practices for First Nations Australians with CKD |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Public awareness, education and self‐management |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Public awareness — to enable First Nations Australians to access information about kidney disease before screening and diagnosis |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Education to support engagement and treatment |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Self‐management programs and initiatives |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Models of care |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Models of care: CKD (pre‐dialysis) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Models of care: CKD (kidney failure) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Models of care: transplantation |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

CARI = Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment; KDOQI = Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- David J Tunnicliffe1,2

- Samantha Bateman3,4

- Melissa Arnold‐Chamney3

- Karen M Dwyer5

- Martin Howell1,2

- Azaria Gebadi1,2

- Shilpa Jesudason6

- Janet Kelly3

- Kelly Lambert7,8

- Sandawan William Majoni9,10

- Dora Oliva11

- Kelli J Owen12,3

- Odette Pearson13,14

- Elizabeth Rix3,15

- Ieyesha Roberts1,2

- Ro‐Anne Stirling‐Kelly1,2,16

- Kimberly Taylor16

- Gary A Wittert3,17

- Katherine Widders1,2

- Adela Yip1,2

- Jonathan Craig10

- Richard K Phoon1,18

- 1 University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

- 2 Centre for Kidney Research, Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, NSW

- 3 University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA

- 4 Central and Northern Adelaide Renal and Transplantation Services, Central Adelaide Local Health Network, Adelaide, SA

- 5 Deakin University, Geelong, VIC

- 6 Kidney Health Australia, Adelaide, SA

- 7 University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW

- 8 Illawarra Health and Medical Research Institute, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, NSW

- 9 Royal Darwin Hospital, Darwin, NT

- 10 Flinders University, Adelaide, SA

- 11 Drug and Alcohol Services, South Australia Health, Adelaide, SA

- 12 Central and Northern Adelaide Renal and Transplantation, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, SA

- 13 Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, SA

- 14 Cancer Research Institute, University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA

- 15 Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW

- 16 NSW Health Mid‐North Coast Local Health District, Sydney, NSW.

- 17 Aboriginal Communities and Families Health Research Alliance, South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute, Adelaide, SA

- 18 Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, SA

- 19 Westmead Hospital, Sydney, NSW

Authors list:

In this Guideline summary, the author Ro‐Anne Stirling‐Kelly was accidentally removed from the authors list. The correction has been updated successfully.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Sydney, as part of the Wiley – The University of Sydney agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

These guidelines were developed in partnership with Kidney Health Australia (KHA). In 2018, KHA received funding from the Australian Government Department of Health to undertake community consultations throughout Australia (alongside Catching Some Air), which have informed the scope and content of these guidelines. KHA also received funding from the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care in 2020 for the writing and dissemination of the guidelines. Caring for Australians and New Zealanders with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guidelines were commissioned to produce guidelines on the management of chronic kidney disease among First Nations Australians.

David Tunnicliffe is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Emerging Leadership 1 Investigator Grant (APP1197337).

CARI Guidelines recognise the unceded land of First Nations Australians on which this work was undertaken and developed. CARI Guidelines thank all the participants of the Catching Some Air and Kidney Health Australia Yarning Kidneys who shared their knowledge, experiences and perspectives to inform these guidelines. We also thank the First Nations Australians who engaged with us and provided feedback on these guidelines to ensure that the guidelines addressed the concerns raised by the community. We thank the Kidney Health Australia Project Team and Advisory Group and the CARI Guideline Steering Committee for their support and direction throughout the phases of the development of these guidelines. CARI Guideline Steering Committee Investigators: Rathika Krishnasamy, Helen Coolican, Min Jun, Vincent Lee, Thu Nguyen, Carla Scuderi, Emily See, Debbie Fortnum, Brydee Johnston, Andrea Viecelli, Rachel Walker and Chandana Guha. KHA Project Team and Advisory Group: Karen Dwyer, Shilpa Jesudason, Chris Forbes, Lisa Murphy, Jason Agostino, Alan Cass, Stephen Cornish, Martin Howell, Jaquelyne Hughes (Wagadagam tribe), Janet Kelly, Rathika Krishnasamy, Dora Oliva, Maria O'Sullivan, Odette Pearson, Suetonia Palmer, Rochelle Pitt (Erubam Le, Quandamooka, Kabi Kabi), Richard Phoon, Breonny Robson, Jess Styles, Donisha Duff and Kimberly Taylor.

CARI Guidelines are the rights and permissions holders of the figures included in this manuscript. All requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to CARI Guidelines, Centre for Kidney Research, Locked Bag 4001, Westmead NSW 2145; or via email at

Karen Dwyer is the current Clinical Director of Kidney Health Australia and Chair of the Clinical Advisory Board and has received consultancy fees, honoraria and research funding from GSK, Servier, Bayer and Novartis; and research funding from Genzyme, A2 Milk Company, ROTRF, CellCept Australia, and Amgen; and is on the clinical advisory board of GMHBA. Gary Wittert has received funding from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency for medico‐legal reports; honoraria from Elsevier for journal editor and international advisory board roles; honoraria from Bayer for an advisory board role; and research funding from Bayer and Lilly. Richard Phoon has received consultancy fees and honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi–Genzyme, and travel support from Novartis. All these potential conflicts have little to no relevance to these guidelines.

- 1. Clarkson C, Jacobs Z, Marwick B, et al. Human occupation of northern Australia by 65 000 years ago. Nature 2017; 547: 306‐310.

- 2. Griffiths K, Coleman C, Lee V, et al. How colonisation determines social justice and Indigenous health — a review of the literature. J Popul Res 2016; 33: 9‐30.

- 3. World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health: final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO, 2008. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO‐IER‐CSDH‐08.1 (viewed Aug 2023).

- 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's health 2014 [Cat. No. AUS 178]. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/d2946c3e‐9b94‐413c‐898c‐aa5219903b8c/16507.pdf.aspx (viewed Apr 2022).

- 5. Marmot MG. Status syndrome: a challenge to medicine. JAMA 2006; 295: 1304‐1307.

- 6. Morton RL, Schlackow I, Mihaylova B, et al. The impact of social disadvantage in moderate‐to‐severe chronic kidney disease: an equity‐focused systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 46‐56.

- 7. Cass A, Cunningham J, Wang Z, Hoy W. Social disadvantage and variation in the incidence of end‐stage renal disease in Australian capital cities. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25: 322‐326.

- 8. Ritte RE, Lawton P, Hughes JT, et al. Chronic kidney disease and socio‐economic status: a cross sectional study. Ethn Health 2020; 25: 93‐109.

- 9. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Chapter 12: end stage kidney disease in Indigenous peoples of Australia and New Zealand: 39th report. Adelaide: ANZDATA Registry, 2016. https://www.anzdata.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2018/04/c12_indigenous_v5.0_20170821.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 10. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Profiles of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease [Cat. No. IHW 229]. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/ca29cd5a‐a0f8‐46a7‐84af‐698675002175/aihw‐ihw‐229.pdf.aspx?inline=true#:~:text=Of%20Indigenous%20adults%20with%20CKD,%2F5%20CKD%20(64%25) (viewed May 2022).

- 11. Holland C; Close the Gap Campaign Steering Committee. Closing the Gap: Progress and priorities report, 2016. Canberra: National Indigenous Australian Agency, 2016. https://closethegap.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2021/10/Progress_priorities_report_CTG_2016_0.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 12. George E, Mackean T, Baum F, et al. Social determinants of Indigenous health and Indigenous rights in policy: a scoping review and analysis of problem representation. Int Indig Policy J 2019; 10: 1‐25.

- 13. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Closing the Gap: report 2020. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2020. https://ctgreport.niaa.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf/closing‐the‐gap‐report‐2020.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 14. Kidney Health Australia. Executive summary “Yarning Kidneys” Community Consultations. Melbourne: Kidney Health Australia, 2020. https://kidney.org.au/uploads/resources/Executive‐Summary‐Yarning‐Kidneys‐Report.pdf (viewed Feb 2022).

- 15. Mick‐Ramsamy L, J Kelly, Duff D, et al. Catching some air: asserting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander information rights in renal disease project — the final report. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2019. https://www.menzies.edu.au/icms_docs/307210_Catching_Some_Air.pdf#:~:text=The%20Catching%20Some%20AIR%20project,and%20Torres%20Strait%20Islander%20people (viewed Feb 2022).

- 16. Bateman S, Arnold‐Chamney M, Jesudason S, et al. Real Ways of Working Together: co‐creating meaningful Aboriginal community consultations to advance kidney care. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46: 614‐621.

- 17. Kelly J, Stevenson T, Arnold‐Chamney M, et al. Aboriginal patients driving kidney and healthcare improvements: recommendations from South Australian community consultations. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46: 622‐629.

- 18. Jesudason S, Oliva D, Barfoot K, et al. Expert Clinician Panel Consultation Report: consultation to inform the development of the Inaugural KHA‐CARI guidelines for management of chronic kidney disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Melbourne: Kidney Health Australia, 2019. https://kidney.org.au/uploads/resources/expert‐clinician‐panel‐consultation‐report.pdf (viewed Feb 2022).

- 19. Institute of Medicine Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines; Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman D, et al; editors. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK209539/ (viewed Aug 2023).

- 20. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 9. Grading evidence and recommendations. Health Res Policy Syst 2006; 4: 21.

- 21. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol 2010; 63: 1308‐1311.

- 22. Tunnicliffe DJ, Bateman S, Arnold‐Chamney M, et al. Recommendations for culturally safe and clinical kidney care for First Nations Australians. Sydney: CARI Guidelines, 2022. https://www.cariguidelines.org/first‐nations‐australian‐guidelines/ (viewed Aug 2023).

- 23. Duff D, Jesudason S, Howell M, Hughes JT. A partnership approach to engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with clinical guideline development for chronic kidney disease. Ren Soc Australas J 2018; 14: 84‐88.

- 24. Noyes J, Booth A, Moore G, et al. Synthesising quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform guidelines on complex interventions: clarifying the purposes, designs and outlining some methods. BMJ Glob Health 2019; 4 (Suppl): e000893.

- 25. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328: 1490.

- 26. Lewin S, Booth A, Glenton C, et al. Applying GRADE‐CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: introduction to the series. Implement Sci 2018; 13 (Suppl): 2.

- 27. Johnson DW, Atai E, Chan M, et al. KHA‐CARI guideline: early chronic kidney disease: detection, prevention and management. Nephrology 2013; 18: 340‐350.

- 28. Kidney Health Australia. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) management in primary care, 4th ed. Melbourne: KHA, 2020. https://kidney.org.au/uploads/resources/CKD‐Management‐in‐Primary‐Care_handbook_2020.1.pdf (viewed Feb 2022).

- 29. Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 2015; 27: 89‐98.

- 30. Devitt J, Anderson K, Cunningham J, et al. Difficult conversations: Australian Indigenous patients’ views on kidney transplantation. BMC Nephrol 2017; 18: 310.

- 31. Rix EF, Barclay L, Stirling J, et al. The perspectives of Aboriginal patients and their health care providers on improving the quality of hemodialysis services: a qualitative study. Hemodial Int 2015; 19: 80‐89.

- 32. Ahmed S, Lawton P, Gorham G, et al. Housing provision and health outcomes among northern territory haemodialysis patients: The dialysis models of care partnership. Nephrology 2018; 23 (Suppl): 26.

- 33. Shashi Bhaskara S, Cherian S, Pawar B, et al. Respite hemodialysis to remote Indigenous Central Australian population and mobile dialysis unit. Nephrology 2012; 17: 47.

- 34. Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, et al. End‐stage renal disease in indigenous Australians: a disease of disadvantage. Ethn Dis 2002; 12: 373‐378.

- 35. Grace BS, Clayton P, Cass A, McDonald SP. Socio‐economic status and incidence of renal replacement therapy: a registry study of Australian patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27: 4173‐4180.

- 36. Hoy WE, Mott SA, McDonald SP. An update on chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal Australians. Clin Nephrol 2020; 93: 124‐128.

- 37. Marrie H, Marrie A. A matrix for identifying, measuring and monitoring institutional racism within public hospitals and health services. Gordonvale: Bukal Consultancy Services, 2014.

- 38. Reilly R, Evans K, Gomersall J, et al. Effectiveness, cost effectiveness, acceptability and implementation barriers/enablers of chronic kidney disease management programs for Indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand and Canada: a systematic review of mixed evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16: 119.

- 39. Ferguson TW, Tangri N, Tan Z, et al. Screening for chronic kidney disease in Canadian indigenous peoples is cost‐effective. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 192‐200.

- 40. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. Chapter 10: end stage kidney disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: 43rd report. Adelaide: ANZDATA Registry, 2021. https://www.anzdata.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2021/09/c10_indigenous_2020_ar_2021_v1.0_20220224_Final.pdf (viewed Nov 2022).

- 41. Lambert K, Bahceci S, Harrison H, et al. Commentary on the 2020 update of the KDOQI clinical practice guideline for nutrition in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2022; 27: 537‐540.

- 42. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Profile of Indigenous Australians [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2021. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias‐welfare/profile‐of‐indigenous‐australians (viewed Oct 2021).

- 43. Cheikh Hassan HI, Chen JH, Murali K. Incidence and factors associated with geographical relocation in patients receiving renal replacement therapy. BMC Nephrol 2020; 21: 249.

- 44. Scholes‐Robertson N, Gutman T, Dominello A, et al. Australian rural caregivers’ experiences in supporting patients with kidney failure to access dialysis and kidney transplantation: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 2022; 80: 773‐782.

- 45. Scholes‐Robertson NJ, Howell M, Gutman T, et al. Patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives on access to kidney replacement therapy in rural communities: systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e037529.

- 46. Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand. Performance report: National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce. Sydney: TSANZ, 2021. https://tsanz.com.au/storage/NIKTT/IHD‐‐‐208‐‐‐4‐BIA3J8Y_NIKTT‐2‐July‐2021‐Performance‐Report.pdf (viewed Oct 2022).

- 47. National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce. Cultural bias initiatives to improve kidney transplantation among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Adelaide: Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand, 2020. https://tsanz.com.au/storage/NIKTT/CulturalBias_PolicyBrief.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 48. Kelly J, Dent P, Owen K, et al. Cultural bias Indigenous kidney care and kidney transplantation report. Adelaide: University of Adelaide, Lowitja Institute, National Indigenous Transplantation Taskforce; 2020. https://tsanz.com.au/storage/NIKTT/CulturalBias_FinalReport.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 49. Menzies School of Health Research. Return to Country: a national platform study to return Indigenous renal patients home. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2020. https://www.menzies.edu.au/page/Research/Projects/Kidney/Return_to_Country/ (viewed Nov 2022).

- 50. Harfield S, Pearson O, Morey K, et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Quality Appraisal Tool. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020; 20: 79.

- 51. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 173.

- 52. Kidney Health Australia. CARI guidelines launch event, 6 October 2022 [video].

Abstract

Introduction: First Nations Australians display remarkable strength and resilience despite the intergenerational impacts of ongoing colonisation. The continuing disadvantage is evident in the higher incidence, prevalence, morbidity and mortality of chronic kidney disease (CKD) among First Nations Australians. Nationwide community consultation (Kidney Health Australia, Yarning Kidneys, and Lowitja Institute, Catching Some Air) identified priority issues for guideline development. These guidelines uniquely prioritised the knowledge of the community, alongside relevant evidence using an adapted GRADE Evidence to Decision framework to develop specific recommendations for the management of CKD among First Nations Australians.

Main recommendations: These guidelines explicitly state that health systems have to measure, monitor and evaluate institutional racism and link it to cultural safety training, as well as increase community and family involvement in clinical care and equitable transport and accommodation. The guidelines recommend earlier CKD screening criteria (age ≥ 18 years) and referral to specialists services with earlier criteria of kidney function (eg, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], ≤ 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, and a sustained decrease in eGFR, > 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year) compared with the general population.

Changes in management as result of the guidelines: Our recommendations prioritise health care service delivery changes to address institutional racism and ensure meaningful cultural safety training. Earlier detection of CKD and referral to nephrologists for First Nations Australians has been recommended to ensure timely implementation to preserve kidney function given the excess burden of disease. Finally, the importance of community with the recognition of involvement in all aspects and stages of treatment together with increased access to care on Country, particularly in rural and remote locations, including dialysis services.