For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have operated and thrived within sovereign societies. The sustained and systematic effects of colonisation — which enabled the combined denial of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's self‐determination, autonomy, leadership, and capability to mobilise health‐benefiting resources — have created the situation in which we find ourselves today of poor health and systemic differences in health care access and outcomes.1 For kidney health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, this situation is illustrated through the persistent inequities in kidney failure incidence rates, health system access, and treatment outcomes.2

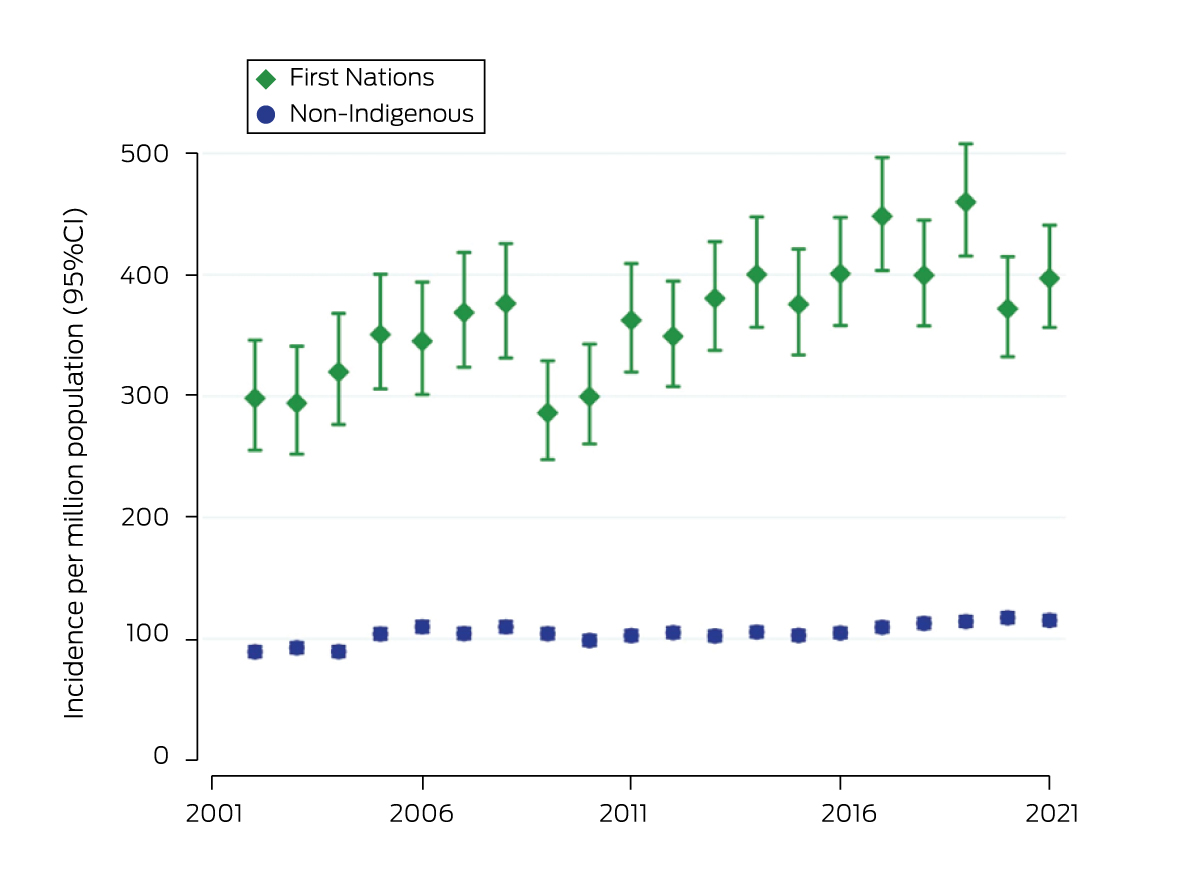

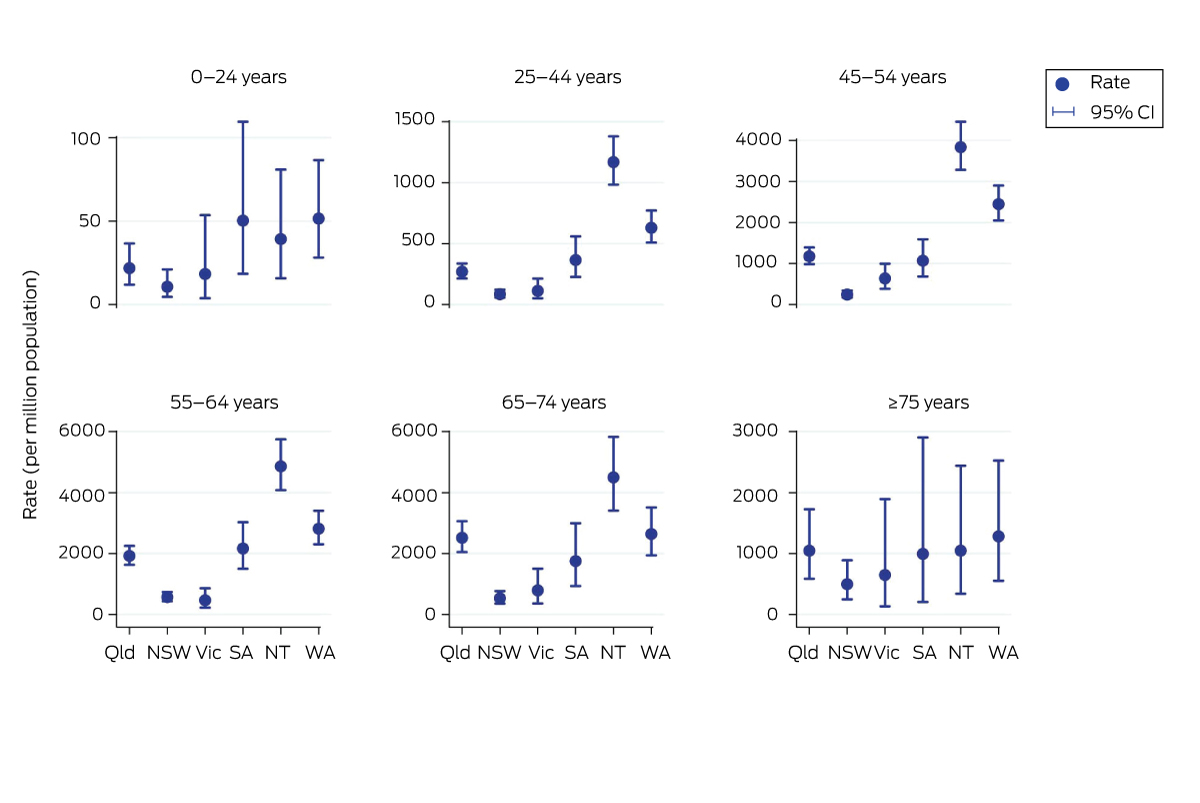

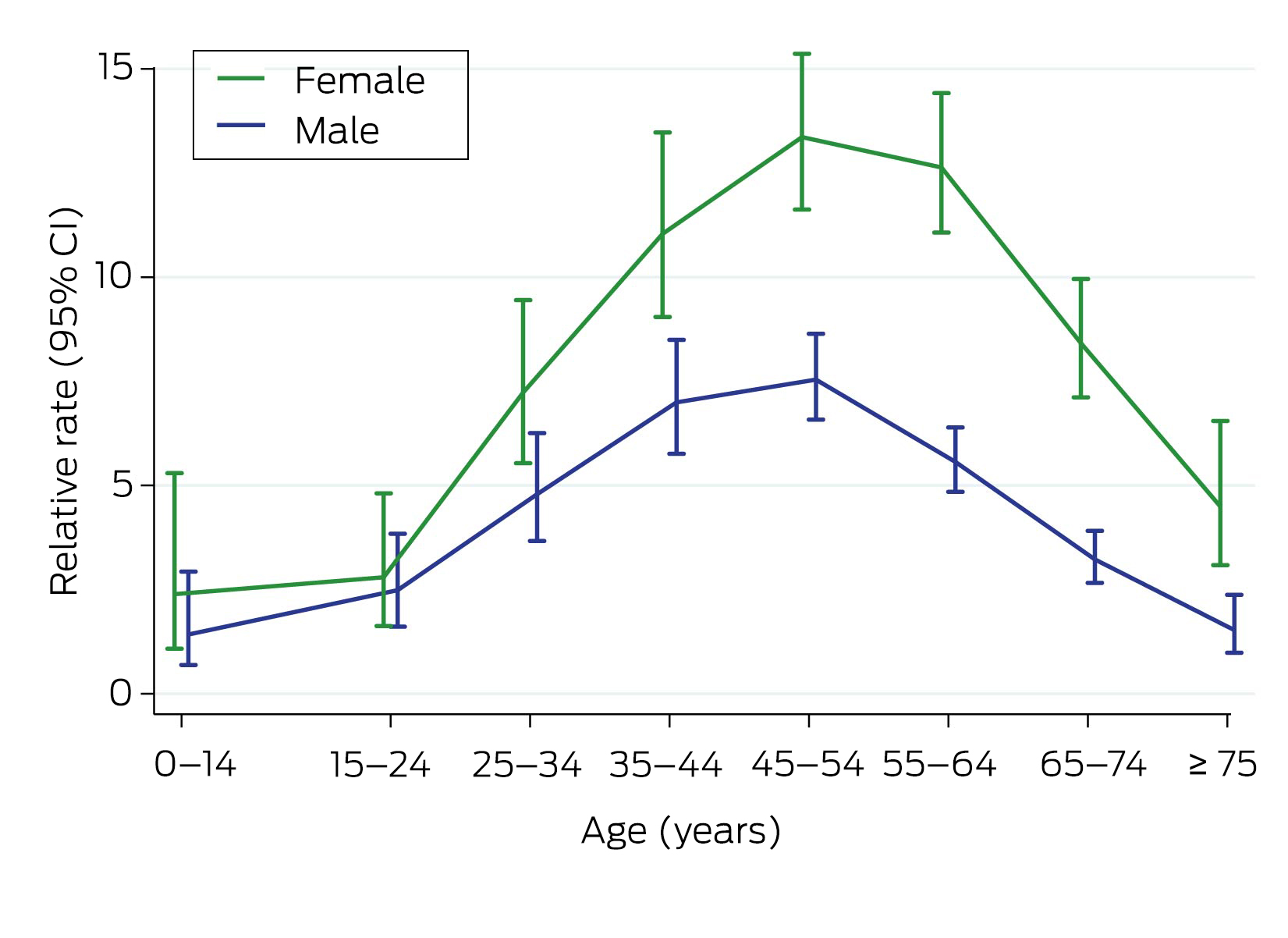

Recorded rates of kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians have risen progressively over the past 40 years, remaining consistently higher than rates for non‐Indigenous Australians (Box 1). This difference is even more marked for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in rural and remote areas.2 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have age‐adjusted incidence rates of kidney replacement therapy (KRT) — dialysis or transplantation — eight to nine times higher than those of non‐Indigenous Australians, with the median age of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who experience kidney failure being nearly 30 years younger than non‐Indigenous people.3 Furthermore, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people receiving KRT, incidence rates vary considerably between location and age (Box 2), as well as sex (Box 3), with people in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, South Australia, and Queensland experiencing higher rates.2

Finally, the modality with which KRT is delivered differs, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people predominantly accessing dialysis through facility‐based haemodialysis, with lower rates of home‐based therapies (peritoneal and home haemodialysis).2 Access to kidney transplantation is substantially lower, reflecting lower waitlisting rates.2

Combined, these disparities mean that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney failure are likely to spend substantially longer (typically years longer) on facility‐based dialysis, away from Country, community, and supportive networks. This dislocation serves to prolong and compound the disconnection, disempowerment and disruption felt by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people when seeking kidney care in Australia.4

Why transplantation matters

For people with kidney failure, kidney transplantation is the preferred treatment option where possible. Not only is transplantation associated with lower mortality, and a substantial improvement in quality of life,5 it is also less expensive in the long term, particularly when considering the cost of dialysis for rural or remote patients.6 Transplantation therefore provides direct clinical benefits to patients and financial benefits to health systems. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kidney transplant recipients and family members — like nearly all other transplant recipients — also affirm the many health and wellbeing benefits of transplantation,7,8 and numerous community consultations have shown that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people want a better understanding of, and access to, transplantation.9,10,11,12

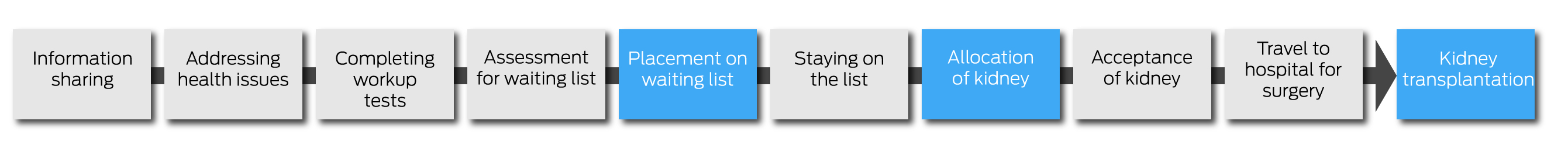

Disparity in access to transplantation has been recognised for many years.13,14,15,16,17,18 Although absolute rates of waitlisting and transplantation have increased among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, substantial inequity remains in rates of waitlisting and transplantation compared with non‐Indigenous populations, as well as age at diagnosis, pre‐transplant treatment modality, and transplantation outcomes.2 Furthermore, the reasons behind the inequity remain. Studies have consistently shown that inequity in access to transplantation cannot be explained by patient‐ or disease‐related factors,14,15 and that the principal block is on getting onto the waiting list, rather than receiving a kidney once on the list.15 Receiving a kidney transplant requires patients to not just meet specific medical requirements, but also to navigate a complex process that includes multiple investigations, appointments, and ongoing reviews (Box 4). Each stage of this pathway can become a barrier to both waitlisting and transplantation.

The difference in waitlisting highlights an important need to focus on the gaps in processes and the barriers within the health system, or more specifically, within clinical services caring for people with kidney disease. To better understand these systemic gaps, in 2018 the Australian Government funded an Expert Panel, through the Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ), to undertake a comprehensive review into the hurdles, service gaps, and practical challenges faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people receiving treatment for kidney disease. The report recommended 35 high priority actions and mapped responsible agencies, identifying where the federal government could strategically enable cross‐jurisdictional consumer‐ and health service‐partnered approaches.19 From there, in March 2019, the then‐federal Minister for Health and the Minister for Indigenous Australians accepted the report, announcing a $2.3 million award for TSANZ to oversee a two‐year project to coordinate cross‐jurisdictional activity.20 This award established a national Taskforce whose overarching aim was to improve access to, and outcomes of, kidney transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Establishing the Taskforce

The National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT) was created to drive the development and implementation of initiatives that targeted knowledge and service delivery gaps identified by the TSANZ report, facilitating improved access to the kidney transplant waitlist and better post‐transplant outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. As this supplement will go on to describe, the Taskforce set out to accomplish this through key objectives around:

- designing and implementing enhanced data collection and reporting processes on pre‐ and post‐transplant outcomes;

- improving the equity and accessibility of transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients by trialling a range of multidisciplinary service models and protocols; and

- reviewing existing initiatives that target cultural bias in health services to facilitate best practice care and support.

To best inform Taskforce action on these objectives, the NIKTT also created a national network of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers and established Indigenous Reference Groups at transplant units around the country.

The development of a national Taskforce was critical to provide a focal point. Although many clinicians, researchers, patients and advocates have worked over the years to improve kidney health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, there has not been a cohesive or coordinated approach to these challenges, nor has there been an opportunity to share and collaborate around service development.

Led by an appointed Chair and Deputy Chair, the Taskforce was comprised of 24 other expert members including nephrologists, nurses, policy makers, researchers and, crucially, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with a lived experience of kidney transplantation and dialysis, as well as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander health workers. Although originally scheduled to be completed within two years, the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic predictably altered the timeline of project implementation and the NIKTT was granted an extension until June 2023.

A strategic focus of the Taskforce was embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's self‐determination and authority into designing models of care that aimed to improve access to kidney transplantation. The NIKTT set out to intentionally consolidate collaboration, partnership and leadership of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as before the onset of the NIKTT, there was extremely limited systematic input of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers into the processes of care in renal units and none in kidney transplant units.

This supplement outlines the recommendations of the Taskforce through describing the outcomes and findings of each objective. We highlight the need for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patient engagement and leadership, the importance of co‐designing models of care unique to local circumstances, and the challenges we still face as a community and health care system seeking to overcome cultural bias and institutional racism. We end this supplement with an overview of the Taskforce's recommendations for next steps and suggest direct actions that systems and services can take to build on the momentum established.

The members of the Taskforce are privileged to be part of this foundational work with health communities and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia. As we progress equity from here, we look forward to working in partnership with patients, communities, health professionals, governments, health organisations, and research institutions to continue to improve access to kidney transplantation.

We begin this supplement with a call to action for readers to join us in improving transplantation equity for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with kidney disease.

We, as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, know what is best for our health and wellbeing. While our people and cultures are strong and resilient, we continue to see harmful policies and practices implemented by government. While this can be difficult to hear, true change exists within discomfort, and progress is made when all parties are open to listening and responding. (Donna Murray, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–203121)

Box 1 – Unadjusted incidence rate of kidney replacement therapy in Australia2

Reproduced with permission of the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry.

Box 2 – Age‐specific incidence rates of treated kidney failure among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, by state and age at kidney replacement therapy start, 2016–20212

NSW = New South Wales; NT = Northern Territory; Qld = Queensland; SA = South Australia; Vic = Victoria; WA = Western Australia. Note the y‐axis scales vary between panels. Figure reproduced with permission of the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry.

Box 3 – Relative incidence rate of treated kidney failure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, by sex, compared with non‐Indigenous Australians, 2016–20212

Reproduced with permission of the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant (ANZDATA) Registry.

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Griffiths K, Coleman C, Lee V, Madden R. How colonisation determines social justice and Indigenous health — a review of the literature. J Pop Research 2016; 33: 9‐30.

- 2. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry. 45th Report, chapter 10: kidney failure in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Adelaide: ANZDATA, 2022. https://www.anzdata.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/06/Chapter‐10‐Kidney‐Failure‐in‐Aboriginal‐and‐Torres‐Strait‐Islander‐Australians.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 3. Hoy WE, Mott SA, McDonald SP. An update on chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal Australians. Clin Nephrol 2020; 93: 124‐128.

- 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: measure 1.10 Kidney disease [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2022. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1‐10‐kidney‐disease (viewed Dec 2022).

- 5. Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 2011; 11: 2093‐2109.

- 6. Gorham G, Howard K, Zhao Y, et al. Cost of dialysis therapies in rural and remote Australia — a micro‐costing analysis. BMC Nephrol 2019; 20: 231.

- 7. Cormick A, Owen K, Turnbull D, Kelly J. Renal healthcare: voicing recommendations from the journey of an Aboriginal woman with chronic kidney disease. Ren Soc Australas J 2022; 18: 88‐100.

- 8. Metro South Health. Thursday Island Elder kidney transplant recipient determined to become beacon of hope [news]. Brisbane: Metro South Health, 2021. https://metrosouth.health.qld.gov.au/news/thursday‐island‐elder‐kidney‐transplant‐recipient‐determined‐to‐become‐beacon‐of‐hope (viewed Dec 2022).

- 9. Hughes JT, Dembski L, Kerrigan V, et al. Gathering perspectives — finding solutions for chronic and end stage kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 2017; 23: 5‐13.

- 10. Kelly J, Stevenson T, Arnold‐Chamney M, et al. Aboriginal patients driving kidney and healthcare improvements: recommendations from South Australian community consultations. Aust N Z J Public Health 2022; 46: 622‐629.

- 11. Mick‐Ramsamy L, Kelly J, Duff D, et al. Catching Some Air: asserting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander information rights in renal disease — the final report. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2019. https://www.menzies.edu.au/icms_docs/307210_Catching_Some_Air.pdf (viewed Dec 2022).

- 12. Tunnicliffe DJ, Bateman S, Arnold‐Chamney M, et al. Recommendations for culturally safe and clinical kidney care for First Nations Australians. Sydney: CARI Guidelines, 2022. https://www.cariguidelines.org/first‐nations‐australian‐guidelines/ (viewed Dec 2022).

- 13. Cass A, Cunningham J, Snelling P, et al. Renal transplantation for Indigenous Australians: identifying the barriers to equitable access. Ethn Health 2003; 8: 111‐119.

- 14. Cass A, Devitt J, Preece C, et al. Barriers to access by Indigenous Australians to kidney transplantation: the IMPAKT study. Nephrology (Carlton) 2004; 9: S144‐S146.

- 15. Khanal N, Lawton PD, Cass A, McDonald SP. Disparity of access to kidney transplantation by Indigenous and non‐Indigenous Australians. Med J Aust 2018; 209: 261‐266. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/209/6/disparity‐access‐kidney‐transplantation‐indigenous‐and‐non‐indigenous

- 16. McDonald SP. Indigenous transplant outcomes in Australia: what the ANZDATA Registry tells us. Nephrology (Carlton) 2004; 9: S138‐S143.

- 17. Tiong MK, Thomas S, Fernandes DK, Cherian S. Examining barriers to timely waitlisting for kidney transplantation for Indigenous Australians in Central Australia. Intern Med J 2020; 52: 288‐294.

- 18. Yeates KE, Cass A, Sequist TD, et al. Indigenous people in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States are less likely to receive renal transplantation. Kidney Int 2009; 76: 659‐664.

- 19. Garrard E, McDonald SP. Improving access to and outcomes of kidney transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in Australia: performance report. Sydney: Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand, 2019. https://tsanz.com.au/storage/NIKTT/TSANZ‐Performance‐Report‐‐‐Improving‐Indigenous‐Transplant‐Outcomes‐Final‐edited‐1.pdf (viewed Dec 2022).

- 20. D'Antoine M, Owen K, McDonald SP. National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT): an update. Transplant Journal of Australasia 2021; 30: 5‐6.

- 21. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐health‐plan‐2021‐2031 (viewed Dec 2022).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley – The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

We acknowledge and thank the Australian Government, represented by the Department of Health and Aged Care, for their funding of the National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT) through an Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme grant (IHD‐208‐4‐BIA3J8Y). This funding supported the salaries of two of the authors (Kelli Owen and Katie Cundale) and covered the publication fees of this MJA supplement.

We thank the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with kidney disease and transplantation who have worked with the NIKTT. We acknowledge that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia face inequities in accessing transplantation due to the systemic barriers that exist within our health care system. We thank everyone for helping us to work towards improving access to transplantation. In addition, we thank all members and supporters of the NIKTT. This supplement, outlining the work of the NIKTT, would not be possible without their dedication, expertise, and sustained commitment to transplantation equity.

No relevant disclosures.