The known: The effectiveness of vaccination for protecting people from hospitalisation with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is typically high, but rapidly wanes with time.

The new: The hospital admission rate for Central Queensland people with COVID‐19 during early 2022 was 0.48%. The estimated effectiveness of vaccination for protecting against disease requiring hospitalisation was 70% after two vaccine doses and 82% after a booster. For First Nations people, vaccine effectiveness was 69%, but the low number of hospitalisations limits the reliability of this estimate.

The implications: Maintaining good vaccination coverage effectively reduces the hospital burden associated with COVID‐19. Improving our understanding of waning immunity is important for optimal booster dose scheduling.

The reported effectiveness of vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) for protecting people from hospitalisation with symptomatic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is typically high, but rapidly wanes with time from vaccination. In England, protection from hospitalisation with the BA.2 SARS‐CoV‐2 variant after a booster dose peaked at 89.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 80.5–94.0%), before declining to 56.5% (95% CI, 38.4–69.3%) at fifteen weeks.1

The effectiveness of vaccination for protecting Australians from hospitalisation with symptomatic COVID‐19 has not been reported. To improve knowledge of vaccine effectiveness and waning immunity in Australia, we therefore evaluated protection against hospitalisation in Central Queensland during the first quarter of 2022, immediately following the end of long term state border closures that had kept most of the population COVID‐19‐naïve.

Methods

In our retrospective cohort study, we applied deterministic methods to link positive SARS‐CoV‐2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results for adult Central Queensland residents (18 years or older) reported to the Notifiable Conditions System (NOCS)2 during 1 January – 31 March 2022 with Central Queensland hospital admissions data and Australian Immunisation Register data.3 The best performing linkage key included the full first name (middle names omitted), full last name, and date of birth. Central Queensland is a coastal region on the Tropic of Capricorn with a population of about 230 000 people; 7.2% are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people (2021 census).4 The regional hospital is in Rockhampton, and there are several rural hospitals and multi‐purpose health services.

Hospitalisation with COVID‐19 was defined as a COVID‐19‐related hospitalisation in a Central Queensland public hospital within 30 days of diagnosis, with the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, tenth revision, Australian modification (ICD‐10‐AM) code B97.2 (“coronavirus as the cause of diseases classified to other chapters”) listed as an additional diagnosis (consistent with Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority guidelines5). Hospital‐in‐the‐home, virtual hospital, and private hospital admissions were not included.

A person was classified as “vaccinated” after completing a primary vaccination course; ie, fourteen days after the second dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech), ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 (AstraZeneca), mRNA‐1273 (Moderna), or another approved SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine. A person was classified as “boosted” fourteen days after receiving one or more booster doses of one of the three major vaccines. People who had received only one vaccine dose prior to diagnosis with COVID‐19 were deemed to be unvaccinated. We classified people as Indigenous people if they were identified as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander in any of the linked records.6

Statistical analysis

We summarise data as means with standard deviations (SDs) or numbers and proportions. In our log‐binomial regression model of people with positive SARS‐CoV‐2 PCR test results, the dependent variable was hospitalisation, and vaccination status was the independent variable. We report vaccine effectiveness — defined as 1 minus the relative risk (risk of hospitalisation for vaccinated people divided by risk for unvaccinated people) — with a 95% confidence interval (CI).7 We used forced entry modelling strategies, incorporating all available variables when possible.8 In adjusted models, vaccine effectiveness estimates were adjusted for age group (under 50 years, 50 years or more), sex, and Indigenous status. Waning immunity was examined by fitting the time between most recent vaccine dose and COVID‐19 diagnosis as an interaction with vaccination status.

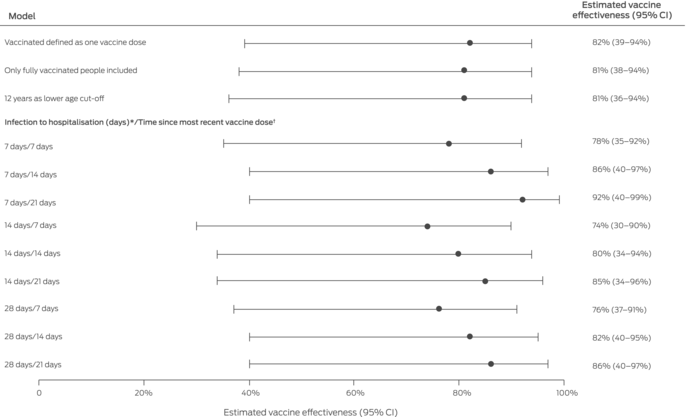

Sensitivity analyses tested the robustness of our model by examining the influence on estimated vaccine effectiveness of different case inclusion criteria (time between infection and hospitalisation of 7, 14, or 28 days) and different vaccinated or boosted status criteria (7, 14, or 21 days since most recent vaccine dose). We also examined the effects of including people who had received only one vaccine dose in the vaccinated group, of deleting cases of partially vaccinated people from our analysis, and of including people aged 12 years or more in our model.

Ethics approval

This study was exempted from formal ethics review by the Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/82361).

Results

Positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test results were recorded during 1 January – 31 March 2022 for 9682 Central Queensland adults, 7244 of whom were deemed vaccinated prior to infection (75%); 5929 people were aged 40 years or younger (62%), 5180 were women (52%) (Box 1). Forty‐seven people were hospitalised with symptomatic COVID‐19 (0.48%); 21 vaccinated people [0.30% of vaccinated people], 26 unvaccinated people [1.1%]), including 25 women (0.5%) and 22 men (0.5%). Thirty people aged 60 years or younger (0.3%) and seventeen over 60 years of age (1.8%) were hospitalised with COVID‐19. Four people required intensive care (0.04%), all but one of whom were unvaccinated; there were no in‐hospital deaths. The Omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variant of concern was the only SARS‐CoV‐2 variant detected in the 409 samples sequenced (Box 1).

Of the 665 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults with positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test results, 401 were deemed vaccinated prior to infection (60%). Six Indigenous people were hospitalised with symptomatic COVID‐19 (0.9%).

Vaccine effectiveness

In univariate analyses, vaccine effectiveness for protecting against hospital admission was 72.4% (95% CI, 49.7–85.4%) for people who had received only a primary vaccination course and 74.4% (95% CI, 27.8–93.9%) for people who had also received a booster shot. Interaction terms for vaccination and Indigenous status, age, and sex did not improve model fit.

In multivariate analyses, vaccine effectiveness was 69.9% (95% CI, 44.3–83.8%) for people who had received only a primary vaccination course and 81.8% (95% CI, 39.5–94.5%) for people who had also received a booster shot. For people who had received only a primary vaccination course, no statistically significant differences by sex, age group, or Indigenous status were found. After adjusting for these three characteristics, people who received a ChAdOx1 primary course were more likely to be hospitalised than those who received NT162b2 (relative risk, 3.49; 95% CI, 0.70–13.4); the likelihood of hospitalisation was similar for people who received BNT162b2 or mRNA‐1273 as the primary course (Box 2). Among vaccinated people, time since most recent vaccine dose did not statistically significantly influence vaccine effectiveness (per month: relative risk, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87–1.35).

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, vaccine effectiveness for protecting against hospital admission was 69.4% (95% CI, –56.5% to 95.8%) for people who had received either a primary vaccination course only or the primary course and a booster shot (multivariate analysis).

Sensitivity analyses in which the criteria for case inclusion (time between diagnosis and hospitalisation) and vaccinated or boosted status (time since most recent vaccine dose) were varied yielded similar results to the main analysis, as did lowering the inclusion age from 18 to 12 years (Box 3; Supporting Information).

Discussion

In our data linkage‐based evaluation, we estimated that the effectiveness of SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination for protecting against hospitalisation with symptomatic COVID‐19 in Central Queensland was about 70% for people who had received a primary course only and about 82% for those who had received a booster dose. Estimated vaccine effectiveness for Indigenous people was about 70% (primary course only or with booster), but, as the number of people hospitalised was very small (six), this figure must be interpreted with caution. All infections for which the virus was sequenced were with Omicron SARS‐CoV‐2 variants.

We found no evidence for waning immunity, but the mean time between most recent vaccine dose and infection was relatively brief (3.84 [SD, 2.05] months). A systematic review found that effectiveness for avoiding the need for hospitalisation was only 20–30% six months after a second vaccine dose;9 a Swedish study found that vaccine effectiveness for protecting against severe COVID‐19 declined from 89% (95% CI, 82–93%) 15–30 days after two vaccine doses to 64% (95% CI, 44–77%) at three months.10 These larger studies indicate that SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines providing more durable immunity are needed, particularly for protecting difficult to reach communities. Similarly, age group and sex did not influence vaccine effectiveness, which suggests that booster vaccination programs do not need to be tailored to specific groups at this stage.

Limitations

Some included hospital admissions may not have been because of severe disease, but for other reasons that increase the likelihood of hospitalisation, such as mild cognitive impairment, poor health literacy, or care not being available at home. Admissions to private hospitals were not included, but there are few private hospitals in Central Queensland, and many did not admit people with COVID‐19 during the study period. As we could include neither cases diagnosed on the basis of rapid antigen tests nor people with asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infections, we will have underestimated the number of infections. We could also have underestimated the number of deaths, as we included only in‐hospital deaths; people may, for instance, have died in aged care facilities or elsewhere without being able to seek hospital care.

Case ascertainment was particularly low in the major regional Indigenous community because about 350 cases were diagnosed using rapid antigen tests, as PCR testing was too slow for outbreak management. We may consequently have missed some hospitalisations of people from this community. This is important, as Indigenous people with COVID‐19 are at risk of poorer outcomes than non‐Indigenous people.11

Conclusion

Only 0.48% of Central Queensland people with PCR‐confirmed Omicron variant SARS‐CoV‐2 infections during the first quarter of 2022 were hospitalised with symptomatic COVID‐19. Vaccine effectiveness with respect to averting the need for hospitalisation was reasonable, and was 82% for people who had received booster doses. Boosters provide additional protection, and improving our understanding of waning immunity is important for optimal booster dose scheduling.

Box 1 – Characteristics of the 9682 Central Queensland people with polymerase chain reaction (PCR)‐confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infections

|

Characteristic |

All people |

Unvaccinated |

Vaccinated |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of people |

9682 |

2438* |

7244 |

||||||||||||

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

18–40 |

5959 (62%) |

1674 (69%) |

4285 (59%) |

||||||||||||

|

41–60 |

2793 (29%) |

604 (25%) |

2189 (30%) |

||||||||||||

|

61–80 |

840 (8.7%) |

134 (5.5%) |

706 (9.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

81 or more |

90 (0.9%) |

26 (1.1%) |

64 (0.9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Women |

5180 (54%) |

1161 (48%) |

4019 (55%) |

||||||||||||

|

Men |

4502 (46%) |

1277 (52%) |

3225 (45%) |

||||||||||||

|

Indigenous status |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander |

665 (6.9%) |

264 (11%) |

401 (5.5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Non‐Indigenous |

8941 (92%) |

2100 (86%) |

6841 (94%) |

||||||||||||

|

Unknown |

76 (0.8%) |

74 (3.0%) |

2 (< 0.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Time since most recent vaccine dose (months), mean (SD) |

— |

NA |

3.84 (2.05) |

||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19‐related hospital admissions |

47 (0.48%) |

26 (1.1%) |

21 (0.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

SARS‐CoV‐2 variant† |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

B.1.1.529 |

21 (5.1%) |

6 (5.2%) |

15 (5.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

BA.1 |

340 (83%) |

100 (86%) |

240 (82%) |

||||||||||||

|

BA.1.1 |

14 (3.4%) |

3 (2.6%) |

11 (3.8%) |

||||||||||||

|

BA.2 |

34 (8.3%) |

7 (6.0%) |

27 (9.2%) |

||||||||||||

|

Not sequenced |

9273 |

2322 |

6951 |

||||||||||||

|

Primary course vaccine |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech) |

5718 (59%) |

NA |

5718 (79%) |

||||||||||||

|

ChAdOx1 (AstraZeneca) |

976 (10%) |

NA |

976 (13%) |

||||||||||||

|

mRNA‐1273 (Moderna) |

542 (5.6%) |

NA |

542 (7.5%) |

||||||||||||

|

Other |

8 (< 0.1%) |

NA |

8 (0.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NA = not applicable; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SD = standard deviation. * Includes 81 people who had received only a single vaccine dose, one of whom was hospitalised with COVID‐19. † All listed variants belong to the Omicron lineage. BA is shorthand for B.1.1.529. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Influence of vaccine brand, sex, age group, and Indigenous status on the likelihood of hospitalisation with symptomatic COVID‐19 of people who had received a primary SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccination course but no booster dose

|

|

Relative risk (95% confidence interval) |

||||||||||||||

|

Characteristic |

Univariate model |

Multivariate model† |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Men |

1.19 (0.44–3.23) |

1.18 (0.43–3.22) |

|||||||||||||

|

Aged 50 years or more |

3.09 (0.71–9.55) |

1.44 (0.25–6.70) |

|||||||||||||

|

Non‐Indigenous Australians |

0.46 (0.10–2.99) |

0.39 (0.10–2.51) |

|||||||||||||

|

Vaccine brand* |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

ChAdOx1 nCoV‐19 (AstraZeneca) |

3.93 (1.26–12.3) |

3.49 (0.70–13.4) |

|||||||||||||

|

mRNA‐1273 (Moderna) |

0.83 (0.11–6.39) |

0.91 (0.05–4.77) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NA = not applicable; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. * Comparator: BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech). † Adjusted for age group, sex, Indigenous status. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Outcomes of sensitivity analyses assessing the influence of criteria for case inclusion and vaccinated or boosted status, and of including people aged 12 years or more in the analysis, on estimated vaccine effectiveness

CI = confidence interval.* Criterion for eligible hospitalisation in main analysis: COVID‐19‐related hospitalisation in a public hospital within 30 days of diagnosis.† Criterion for being vaccinated or boosted in main analysis: COVID‐19‐related hospitalisation within fourteen days of a primary vaccination course second dose or of a booster dose respectively.

Received 6 January 2023, accepted 11 May 2023

- Nicolas R Smoll1,2,3

- Mahmudul Hassan Al Imam1,3

- Connie Shulz1,4

- Robert Booy5

- Gulam Khandaker1,3,5

- 1 Central Queensland Public Health Unit, Central Queensland Hospital and Health Service, Rockhampton, QLD

- 2 The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 3 Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, QLD

- 4 National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT

- 5 The University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW

Correspondence: n.smoll@uq.edu.au

Data sharing

The research data can be accessed by contacting the corresponding author.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley – The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This investigation was supported by a Royal Australasian College of Physicians 2023 Research Development Grant (2023RDG00006) awarded to Nicolas Smoll, and the Queensland Advancing Clinical Research Fellowship (PJ‐70405‐A034‐X000‐HE2993) awarded to Gulam Khandaker. The funding bodies did not have any role in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the decision to submit the manuscript.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Kirsebom FCM, Andrews N, Stowe J, et al. COVID‐19 vaccine effectiveness against the omicron (BA.2) variant in England. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22: 931‐933.

- 2. Queensland Health. Notifiable conditions register. Updated 3 Feb 2016. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical‐practice/guidelines‐procedures/diseases‐infection/notifiable‐conditions/register (viewed June 2023).

- 3. Services Australia. Australian Immunisation Register. Updated 7 July 2022. https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/australian‐immunisation‐register (viewed June 2023).

- 4. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Central Queensland. 2021 Census: All persons QuickStats. https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find‐census‐data/quickstats/2021/308 (viewed June 2023).

- 5. Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. How to classify COVID‐19. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health‐care/classification/how‐classify‐covid‐19 (viewed Dec 2022).

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Australian Bureau of Statistics. National best practice guidelines for data linkage activities relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Cat. no. IHW 74). 9 July 2012. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous‐australians/national‐best‐practice‐guidelines‐for‐data‐linkage/summary (viewed June 2023).

- 7. Halloran ME, Longini IM, Struchiner CJ. Design and interpretation of vaccine field studies. Epidemiol Rev 1999; 21: 73‐88.

- 8. Mundry R, Nunn CL. Stepwise model fitting and statistical inference: turning noise into signal pollution. Am Nat 2009; 173: 119‐123.

- 9. Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu‐Raddad LJ, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta‐regression. Lancet 2022; 399: 924‐944.

- 10. Nordström P, Ballin M, Nordström A. Risk of infection, hospitalisation, and death up to 9 months after a second dose of COVID‐19 vaccine: a retrospective, total population cohort study in Sweden. Lancet 2022; 399: 814‐823.

- 11. Yashadhana A, Pollard‐Wharton N, Zwi AB, Biles B. Indigenous Australians at increased risk of COVID‐19 due to existing health and socioeconomic inequities. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2020; 1: 100007.

Abstract

Objective: To estimate the effectiveness of vaccination against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) for protecting people in a largely coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19)‐naïve regional population from hospitalisation with symptomatic COVID‐19.

Design: Retrospective cohort study; analysis of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test results linked with Central Queensland hospitals admissions data and Australian Immunisation Register data.

Setting, participants: Adult residents of Central Queensland, 1 January – 31 March 2022.

Main outcome measures: Vaccine effectiveness (1 – relative risk of hospitalisation for vaccinated and unvaccinated people) with respect to protecting against hospitalisation with symptomatic COVID‐19 after primary vaccination course only (two doses of an approved SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine) and after a booster vaccine dose.

Results: Positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test results were recorded during 1 January – 31 March 2022 for 9682 adults, 7244 of whom had been vaccinated (75%); 5929 people were aged 40 years or younger (62%), 5180 were women (52%). Forty‐seven people were admitted to hospital with COVID‐19 (0.48%), four required intensive care (0.04%); there were no in‐hospital deaths. Vaccine effectiveness was 69.9% (95% confidence interval [CI], 44.3–83.8%) for people who had received only a primary vaccination course and 81.8% (95% CI, 39.5–94.5%) for people who had also received a booster. Of the 665 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults with positive SARS‐CoV‐2 test results, 401 had been vaccinated (60%). Six Indigenous people were hospitalised with symptomatic COVID‐19 (0.9%); vaccine effectiveness was 69.4% (95% CI, –56.5% to 95.8%) for Indigenous people who had received a primary vaccination course only or the primary course and a booster.

Conclusion: The hospitalisation rate for Central Queensland people with PCR‐confirmed Omicron variant SARS‐CoV‐2 infections during the first quarter of 2022 was low, indicating the protection afforded by vaccination and the value of booster vaccine doses.