Rural communities across Australia face an ongoing shortage of doctors, which reduces access to care and leads to poorer health outcomes for people living in rural areas. Significant undersupply exists, particularly in rural general practice, priority-need generalist specialties and rural generalism.1,2 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic exacerbated vacancies as immigration of international medical graduates came to a standstill and interstate movement of rural locum doctors reduced. The recently released National Medical Workforce Strategy emphasises the need to grow a workforce of our own that is fit for purpose, to deliver culturally safe and context-specific medical services to all Australian people.1 Over the past 20 years, there have been significant political and educational initiatives to increase the rural workforce, with accompanying research investigating their outcomes.3 Eminent rural researcher Denese Playford wrote:

These data collectively build a portrait of candidates who are more likely to work rurally. The portrait suggests that a very convincing set of known factors are at play: rural background, lower socio‐economic status, locally‐born, quarantined rural pathway … entering with rural intent, Medical Rural Bonded Scholarship holders.4

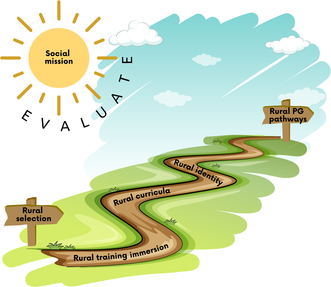

Selection and support of rural students, rural placement immersions and development of comprehensive rural medical programs are within the control of medical schools and supported by Australian evidence. The pathways to rural practice are rich and varied. Successful approaches tailor these elements to local resources, needs and priorities (Box 1). In this article, we describe the elements of a comprehensive approach for medical schools. The Aristotelian notion that “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts” is important and medical schools need to apply a comprehensive approach to deliver more graduates who will work rurally.

Enact a social mission statement for rural service

Social accountability obliges medical schools to focus their own research, service and education undertakings specifically on addressing the health needs of their local community, region and/or nation. Priority health needs are to be identified jointly by local communities, health care organisations, health professionals and the government.5 As the majority of medical schools remain centred in large metropolitan areas, it is essential that these medical schools adopt a rural social mission statement as a way of expressing their commitment. Overt commitment enables the medical schools to put in place the strategies outlined below to produce more rural doctors, and build a supportive environment to fulfil this mission.6

Select for rural workforce outcomes

Increase rural background cohort numbers

Graduates from rural backgrounds are more likely to work in rural practice (odds ratio, 2.6 to 3.9).7,8,9,10,11 This “rural background effect” is independent of rural clinical training, but is augmented by it.7,8,9,12 The effect endures throughout postgraduate career stages,8,13 and has been found in some studies to increase over time.14 Rural background graduates are more likely to commence in rural practice, move to rural practice and remain in rural practice.13 Since 1995, in an effort to meet equity‐of‐access goals, the Commonwealth Government has mandated that 25% of medical student Commonwealth‐supported places are allocated to students with a rural background.15 With 28% of Australians living in rural areas,16 more recently funded rural programs, such as the Murray–Darling Medical Schools Network, have higher mandated proportions of rural background places (up to 100%).17

Medical school selections traditionally use university entrance examinations, which are expensive and less easily accessed from rural areas.18 Admitting more students from a rural background has been achieved in different ways across Australia. Equity adjustments have been used by many universities, such as adjusting academic and entrance exam scores, or keeping selection methods consistent and creating specific rural quotas. Other medical programs have adopted specific rural selection tools, including written personal statements and interviews, using community members to understand candidates’ rural interests.19,20,21,22 Despite these adjustments to admissions, rural background students demonstrate the same academic outcomes in medical school as other student cohorts admitted with higher entry scores.23

Select students from higher rurality locations

The Modified Monash Model (MMM) categorises the rurality of Australian communities using a scale from 1 for metropolitan to 7 for very remote.24 Including MMM2 communities (regional, population > 50 000) in selection targets risks displacing students from more isolated locations. Applying a sub‐quota to MMM3–MMM7 communities ensures that students from smaller communities and remote Australia enter medical school. This focus is an important step forward in rural selection. Targeting selection of MMM3–MMM7 students from a specific geographic region within a university's regional footprint is a promising emerging strategy — it is informed by evidence that rural students are more likely to return to their own or a similar rural community.12,25

Many students in rural schools, particularly those from higher rurality areas, do not see medicine as an achievable career. Geographical, financial, social and self‐efficacy barriers prevent many potential rural applicants from considering medicine. Medical schools can play a key role in leading community‐engaged recruitment and support programs for high school students and other people living in rural areas who are eligible to access graduate‐entry medical schools. The impact of these recruitment programs can increase applications from students in rural areas.26

Provide early support, not constraints

Strongly coercive interventions, such as bonded medical places, are associated with comparatively lower rural retention than interventions that involve less coercion.27 Currently about 25% of all Commonwealth‐supported medical students are bonded to areas of workforce need (including rural areas) for 3 years.28 Medical student bonding arrangements have reduced over time, due to limited evidence of long term success. Bonding conveys messages at the start of medical school that rural is less attractive, and it perpetuates inappropriate deficit discourse around rural practice. The current policy initiative of reducing Higher Education Loan Program debt for rural doctors is likely to have a much more positive impact.29 Promoting this financial support to students will assist with their choices to move to and stay in rural areas, but more needs to be done to overcome financial pressures for students from disadvantaged backgrounds during medical school.

Rural students are a heterogeneous group, with potentially vast differences in rurality of background, socio‐economic status, and personal agency. When available, generous scholarships targeting rural students enable those experiencing financial hardship to participate in medical training. Access to safe, student‐friendly and affordable accommodation is invaluable for student success and rural retention. University‐owned and subsidised housing allows students to transition into medical school and access clinical placements in a range of locations.

Make medical training locations more accessible for rural people

Few medical courses are wholly based outside of capital cities in Australia.21 In 2019, the Commonwealth Government recognised the value of comprehensive rurally based programs that are more accessible for rural students by introducing legislation to reallocate 2% of medical school Commonwealth‐supported places from urban medical schools to rural end‐to‐end programs every 3 years. This redistribution of medical school training places, which commenced in 2020, facilitated the recent establishment of medical programs in regional areas of New South Wales and Victoria.17 Before the COVID‐19 pandemic began, this redistribution of medical places to rural programs may have been enough to provide an adequate rural medical workforce. Recent significantly reduced inward immigration of international medical graduates means that this policy needs to be reviewed. An expansion of Commonwealth‐supported medical student places is required in rurally located end‐to‐end medical school programs, rather than a reliance solely on redistribution, to ensure that each state has at least one rural medical school program that provides remote or rural training from the start to the completion of the medical degree. A national collaboration could share medical education and remote teaching resources to support this initiative, with the Federation of Rural Australian Medical Educators well placed to facilitate this (https://ausframe.org/).

Highlight rural medicine in medical school curricula

Showcase diverse rural contexts

Medical curricula and assessments shape students’ views of rural career options.30 Traditional medical school teaching is predominantly metropolitan focused and specialist led. Medical students report that denigration of both rural doctors and general practice is still commonplace in Australia.31 Attitudes which fail to recognise the expertise of generalists influence students’ career choices away from rural practice. Medical schools with strong academic engagement by rural clinicians illustrate the value of rural doctors. Integrating rural clinical cases and management plans for rural practice within the formal curriculum can reinforce positive and realistic messages about rural medicine in Australia.30 Australian medical schools with MD programs require students to undertake research, providing an opportunity for students to undertake rural projects that contribute to rural communities, which in turn can draw students to rural careers.

Teach generalist ways of working

As generalists, rural doctors deal with high levels of complexity and uncertainty in clinical practice. Students who are ill prepared for clinical complexity can avoid specialties that have high loads of uncertainty. Modern curricula need to prepare students explicitly for uncertainty, multimorbidity, shared decision making and communication across clinical settings. Clinical cases set in rural contexts provide opportunities to build medical students’ generalist approaches to clinical care. Having rural doctors teach core medical content will encourage a broader scope of practice for all students. In addition, medical students need to learn to work in multidisciplinary teams. Ensuring that a broad range of rural health practitioners teach medical students alongside nursing and allied health students will promote good foundations for future work practices. These changes in the curriculum will ensure all medical students have the skills for 21st century health care.

Invest in rural training pathways

Immerse students in a rural place

Immersive rural training remains a cornerstone for producing more rural doctors. Australian rural clinical schools have provided a generation of medical students with a year or more of rural clinical experience.32 Placement types vary from traditional hospital rotations in regional centres, with arguably less rural context, to placements based in general practices in small rural communities where students interleave general practice and hospital experience, often supervised by rural generalists.33 Rural placements enable students to build connections with rural clinicians and communities. Their influence can range from cementing intent for students already interested in rural practice to changing intent of students primarily interested in metropolitan practice.9,34 Longitudinal integrated rural clinical placements demonstrate consistently excellent academic outcomes and increased rural medical workforce outcomes by up to seven times those of metropolitan medical student clinical training.8,35 These programs, when situated in small rural towns, result in graduates who are up to five times more likely to work in small rural towns.36 This workforce outcome takes time, particularly in communities that are not big enough to provide prevocational training. Many rural clinical school graduates who have to leave rural areas for their postgraduate training come back 5–10 years after graduation.37

Students who become rural doctors often spend longer than their peers being undecided about their specialty intentions, highlighting the importance of regular positive rural experiences to promote the uptake of general practice and rural practice.38 Longer duration (18–24 versus 12 months) of rural training is associated with a threefold increase in returning to practise in the same rural region after training.7,39

Incrementally stronger associations exist for longer duration, a combination of regional hospital and general practice experience, greater remoteness and multiple placements.7,10,32 Apart from duration, there may be specific place‐based effects. For example, the Rural Clinical School of Western Australia distributes rural medical workforce in a clearly geographically patterned way, with Broome acting as a bridge to the remote north of Australia.40 In Victoria, those selected from a specific region and having greater than one year of rural training in that region had a 17.4 times increased chance of working in that same rural region compared with urban background students who had completed fewer than 12 weeks of training in the region.25

In rural communities, students make an authentic contribution to the clinical care of patients.41 They are seen by local people as contributing members of the community, and these meaningful relationships shape their learning and professional identity.41 As students on full year rural placements engage in community social activities, such as participation in sport, choir or church, they develop individual informal relationships with community members. Adopting a community‐engaged approach to training also includes facilitating rural communities to engage in the selection and education of students as patient‐experts and simulated patients. Prolonged rural placement experiences trigger aspirational, intellectual and emotional responses, particularly in students who have a strong motivation to help others and who value teamwork.42 Accordingly, students are drawn in and bound to their “own” town.43

Develop medical students’ rural identity

For many students choosing a rural career, this requires simultaneous choices of rural location and specialty discipline, while urban medical careers tend to be shaped first by chosen specialty and later by location of practice.38 A medical school's social and cultural context shapes who students become (eg, rural community member), not solely what they practise (ie, discipline interest).33,44 This highlights the importance of fostering rural self‐identity during medical school.

Rural practice self‐efficacy is an individual's sense of self‐confidence to thrive working in rural practice.45 It correlates with medical student rural practice intent and increased remoteness of location of practice after graduation.45,46,47 Rural doctors describe their practice as involving connection with their communities, comfort with clinical uncertainties and preparedness to undertake clinical activities at the edge of their scope.48 Students on rural placements are immersed in this culture of rural medicine, see others like them in rural practice, and thereby develop rural practice self‐efficacy.45

Students’ aspirations and expectations are strongly influenced by peers. Rural health clubs at universities celebrate and support students’ interests and facilitate contact with like‐minded peers. Students who undertake a rural stream in medical school develop strong ties, before and during rural placements, with each other and with mentors.49 Extended rural placements help students build firm friendships in the student group on location and between students in other similar rural sites. In rural areas, a strong community of practice is essential for developing and sustaining clinicians who thrive.50

An apprenticeship‐style mentoring model between rural medical practitioners and rural students enables students to feel supported and trained appropriately for rural and remote practice.51 Close working relationships between learners and their rural clinical supervisors enable rural professional identity formation over time.41,52 Mentors have a key influence on graduates’ career choices and practice locations.53 The John Flynn Placement Program, which previously supported medical students to undertake extracurricular rural placements (2 weeks annually for 4 years), demonstrated positive effects of mentorship on rural practice intent.11

Value rural practitioners and rural academics

The rural medical workforce is under stress. Maintaining and developing training capacity is vital for all rural programs and Australia's future rural medical workforce. Junior doctors, registrars and international medical graduates compete for limited supervisor time and clinical space. Rural clinical schools play an important role in developing educationally supportive communities of practice for rural doctors. Schools also advocate for increased resources for rural areas, including financial remuneration for teaching and research, and clinical training infrastructure in rural general practices and hospitals. With proposed expansion of rural medical training pathways at all levels, the importance of appropriate support for rural clinical teachers, to ensure high quality clinical supervision, cannot be underestimated.

Rural academic positions provide career diversity in rural Australia. Rural medical programs develop and support rural doctors to have blended roles, including clinician–teacher and clinical academic. Medical schools that include rural academics in curriculum design and delivery, assessment, research projects and wider opportunities within the university can improve advancement and longevity of engagement of rural staff.54 Having rural academics in senior medical school management teams secures rural oversight of rural missions. Rural clinical schools can provide academic skills for general practitioner and specialist registrars, enabling them to complete their training rurally. Many of these registrars will stay on or come back to the rural centre that provided this academic environment.32

Facilitate rural prevocational and specialist training

Developing and sustaining rural and regional postgraduate training pathways is critical for supporting doctors to stay in rural areas.55 The Commonwealth Government's regional training hubs initiative funds rural clinical schools to develop, promote and sustain intern and vocational training opportunities in rural and remote Australia. Importantly, rural clinical schools connect students and junior doctors to vertically integrated training opportunities. Through regional training hubs, medical schools are increasingly engaging with other stakeholders contributing to workforce outcomes to maximise return on government investment and collaborate to address Australia's rural workforce needs. Several specialist training programs have now adopted a rural health equity strategy which sees rural background graduates privileged in college selection processes, particularly for rural training positions.56 The Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine has recognised the value of rural connection and has incorporated a demonstrated connection with rural communities into its selection process for all candidates.57

Evaluate and recommit to the social mission

Ongoing research into medical school influences on rural career choice will continue to influence medical school policy. Small changes in admissions policies can effect significant changes in terms of rural students entering medical school. Reporting on outcomes of rural pathways within the medical course must hold medical schools to account, ensure appropriate participation of students from under‐represented rural communities, and enable continuous quality improvement of rural training pathways. Tracking rural student progress throughout the course can facilitate access to social and academic supports when required to retain these students. Finally, the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency collects data on location of practice, which enables universities to track their graduates to understand the impact on the end goal — more rural doctors. The rural workforce outcomes of medical school interventions can take many years to eventuate and will remain dependent on other factors such as specialty choice, rural postgraduate training opportunities, and individual, family and partner commitments.

Conclusion

Rural clinical schools in Australia have demonstrated the compounding effect of rural background, generalist intent, rural immersion, rural curricula, rural practice self‐efficacy and rural identity on rural practice outcomes (Box 2). Medical schools have an obligation to direct their activities to addressing priority health needs in rural areas. Incorporating a comprehensive approach to all the elements of selection, rural immersion and rural curriculum, based on a defined social mission and geographic binding to the communities they serve, will enable students to develop their skills and careers in rural areas across Australia.

Box 1 – A comprehensive approach for medical schools to develop more rural doctors

- Enact a social mission statement for rural service

- Select for rural workforce outcomes

- ‣ Increase rural background cohort numbers

- ‣ Select students from higher rurality locations

- ‣ Provide early support, not constraints

- Make medical training locations more accessible for rural people

- Highlight rural medicine in medical school curricula

- ‣ Showcase diverse rural contexts

- ‣ Teach generalist ways of working

- Invest in rural training pathways

- ‣ Immerse students in a rural place

- ‣ Develop medical students’ rural identity

- ‣ Value rural practitioners and rural academics

- Facilitate rural prevocational and specialist training

- Evaluate and recommit to the social mission

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National Medical Workforce Strategy scoping framework. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐medical‐workforce‐strategy‐scoping‐framework (viewed May 2023).

- 2. McGrail MR, Russell DJ. Australia's rural medical workforce: supply from its medical schools against career stage, gender and rural‐origin. Aust J Rural Health 2017; 25: 298‐305.

- 3. Walters LK, McGrail MR, Carson DB, et al. Where to next for rural general practice policy and research in Australia? Med J Aust 2017; 207: 56‐58. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/207/2/where‐next‐rural‐general‐practice‐policy‐and‐research‐australia

- 4. Playford DE, Mercer A, Carr SE, Puddey IB. Likelihood of rural practice in medical school entrants with prior tertiary experience. Med Teach 2019; 41: 765‐772.

- 5. Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand. Social accountability. https://medicaldeans.org.au/priorities/social‐accountability (viewed Sept 2022).

- 6. Hays R. Developing a rural medical school in Australia. In: Chater AB, Rourke J, Strasser R, et al, editors. WONCA rural medical education guidebook. Bangkok: World Organization of Family Doctors, 2014. https://ruralwonca.org/wp‐content/uploads/2.1.7‐Hays‐Rural‐Medical‐School‐in‐Australia.pdf (viewed Feb 2023).

- 7. O'Sullivan B, McGrail M, Russell D, et al. Duration and setting of rural immersion during the medical degree relates to rural work outcomes. Med Educ 2018; 52: 803‐815.

- 8. Fuller L, Beattie J, Versace V. Graduate rural work outcomes of the first 8 years of a medical school: what can we learn about student selection and clinical school training pathways? Aust J Rural Health 2021; 29: 181‐190.

- 9. Playford D, Ngo H, Gupta S, Puddey IB. Opting for rural practice: the influence of medical student origin, intention and immersion experience. Med J Aust 2017; 207: 154‐158. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/207/4/opting‐rural‐practice‐influence‐medical‐student‐origin‐intention‐and‐immersion

- 10. O'Sullivan BG, McGrail MR. Effective dimensions of rural undergraduate training and the value of training policies for encouraging rural work. Med Educ 2020; 54: 364‐374.

- 11. Young L, Kent L, Walters L. The John Flynn Placement Program: evidence for repeated rural exposure for medical students. Aust J Rural Health 2011; 19: 147‐153.

- 12. McGrail MR, O'Sullivan BG. Increasing doctors working in specific rural regions through selection from and training in the same region: national evidence from Australia. Hum Resour Health 2021; 19: 132.

- 13. Seal AN, Playford D, McGrail MR, et al. Influence of rural clinical school experience and rural origin on practising in rural communities five and eight years after graduation. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 572‐577. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/11/influence‐rural‐clinical‐school‐experience‐and‐rural‐origin‐practising‐rural

- 14. Ray RA, Woolley T, Sen Gupta T. James Cook University's rurally orientated medical school selection process: quality graduates and positive workforce outcomes. Rural Remote Health 2015; 15: 3424.

- 15. KBC Australia. Independent evaluation of the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program. Orange: KBC Australia, 2020. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐03/evaluation‐of‐the‐rural‐health‐multidisciplinary‐training‐rhmt‐program‐final‐report.pdf (viewed May 2023).

- 16. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote health. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural‐remote‐australians/rural‐and‐remote‐health (viewed June 2023).

- 17. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Murray–Darling Medical Schools Network. https://www.health.gov.au/our‐work/murray‐darling‐medical‐schools‐network (viewed Feb 2023).

- 18. Griffin B, Horton GL, Lampe L, et al. The change from UMAT to UCAT for undergraduate medical school applicants: impact on selection outcomes. Med J Aust 2021; 214: 84‐89. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/214/2/change‐umat‐ucat‐undergraduate‐medical‐school‐applicants‐impact‐selection

- 19. Eley DS, Leung JK, Campbell N, Cloninger CR. Tolerance of ambiguity, perfectionism and resilience are associated with personality profiles of medical students oriented to rural practice. Med Teach 2017; 39: 512‐519.

- 20. Puddey IB, Mercer A, Playford DE, Riley GJ. Medical student selection criteria and socio‐demographic factors as predictors of ultimately working rurally after graduation. BMC Med Educ 2015; 15: 74.

- 21. Sen Gupta T, Johnson P, Rasalam R, Hays R. Growth of the James Cook University Medical Program: maintaining quality, continuing the vision, developing postgraduate pathways. Med Teach 2018; 40: 495‐500.

- 22. Stagg P, Rosenthal DR. Why community members want to participate in the selection of students into medical school. Rural Remote Health 2012; 12: 1954.

- 23. Hay M, Mercer A, Lichtwark I, et al. Selecting for a sustainable workforce to meet the future healthcare needs of rural communities in Australia. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2017; 22: 533‐551.

- 24. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Modified Monash Model. https://www.health.gov.au/health‐topics/rural‐health‐workforce/classifications/mmm (viewed Feb 2023).

- 25. McGrail MR, O'Sullivan BG, Russell DJ. Rural training pathways: the return rate of doctors to work in the same region as their basic medical training. Hum Resour Health 2018; 16: 56.

- 26. Reeves NS, Cheek C, Hays R, et al. Increasing interest of students from under‐represented groups in medicine—a systematised review. Aust J Rural Health 2020; 28: 236‐244.

- 27. Russell D, Mathew S, Fitts M, et al. Interventions for health workforce retention in rural and remote areas: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health 2021; 19: 103.

- 28. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Bonded Medical Program. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives‐and‐programs/bonded‐medical‐program (viewed Sept 2022).

- 29. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. HELP for rural doctors and nurse practitioners. https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives‐and‐programs/help‐for‐rural‐doctors‐and‐nurse‐practitioners (viewed Sept 2022).

- 30. Hays R, Sen Gupta T. Ruralising medical curricula: the importance of context in problem design. Aust J Rural Health 2003; 11: 15‐17.

- 31. La Forgia A, Williams M, Williams S, et al. Are Australian rural clinical school students’ career choices influenced by perceived opinions of primary care? Evidence from the national Federation of Rural Australian Medical Educators survey. Aust J Rural Health 2021; 29: 373‐381.

- 32. McGirr J, Seal A, Barnard A, et al. The Australian Rural Clinical School (RCS) program supports rural medical workforce: evidence from a cross‐sectional study of 12 RCSs. Rural Remote Health 2019; 19: 4971.

- 33. Greenhill J, Richards JN, Mahoney S, et al. Transformative learning in medical education: context matters, a South Australian longitudinal study. J Transform Educ 2018; 16: 58‐75.

- 34. Playford D, Ngo H, Puddey I. Intention mutability and translation of rural intention into actual rural medical practice. Med Educ 2021; 55: 496‐504.

- 35. Worley PS. The immediate academic impact on medical students of basing an entire clinical year in rural general practice [PhD thesis]. Adelaide: Flinders University, 2002.

- 36. Campbell DG, McGrail MR, O'Sullivan BG, Russell DJ. Outcomes of a 1‐year longitudinal integrated medical clerkship in small rural Victorian communities. Rural Remote Health 2019; 19: 4987.

- 37. Moore M, Burgis‐Kasthala S, Barnard A, et al. Rural clinical school students do come back: but it may take time. Aust J Gen Pract 2018; 47: 812‐814.

- 38. McGrail M, O'Sullivan B, Gurney T, et al. Exploring doctors’ emerging commitment to rural and general practice roles over their early career. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 11835.

- 39. Kondalsamy‐Chennakesavan S, Eley DS, Ranmuthugala G, et al. Determinants of rural practice: positive interaction between rural background and rural undergraduate training. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 41‐45. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/202/1/determinants‐rural‐practice‐positive‐interaction‐between‐rural‐background‐and

- 40. Playford DE, Burkitt T, Atkinson D. Social network analysis of rural medical networks after medical school immersion in a rural clinical school. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19: 305.

- 41. Kelly L, Walters L, Rosenthal D. Community‐based medical education: is success a result of meaningful personal learning experiences? Educ Health (Abingdon) 2014; 27: 47‐50.

- 42. Bingham A, O'Sullivan B, Couch D, et al. How rural immersion training influences rural work orientation of medical students: theory building through realist evaluation. Med Teach 2021; 43: 1398‐1405.

- 43. Walters L, Stagg P, Conradie H, et al. Community engagement by two Australian rural clinical schools. Australas J Univ‐Community Engagem 2011; 6: 27‐56.

- 44. Hill P, Jennaway M, O'Sullivan B. General physicians and paediatricians in rural Australia: the social construction of professional identity. Med J Aust 2021; 215 (1 Suppl): S15‐S19. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2021/215/1/building‐sustainable‐rural‐physician‐workforce

- 45. Isaac V, Walters L, McLachlan C. Association between self‐efficacy, career interest and rural career intent in Australian medical students with rural clinical school experience. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e009574.

- 46. Bentley M, Dummond N, Isaac V, et al. Doctors’ rural practice self‐efficacy is associated with current and intended small rural locations of practice. Aust J Rural Health 2019: 27: 146‐152.

- 47. Raftery D, Isaac V, Walters L. What are the factors that increase medical students’ interest in small rural and remote practice in Australia? Aust J Rural Health 2021; 29: 34‐40.

- 48. Konkin J, Grave L, Cockburn E, et al. Exploration of rural physicians’ lived experience of practising outside their usual scope of practice to provide access to essential medical care (clinical courage): an international phenomenological study. BMJ Open 2020: 10: e037705.

- 49. Burgis‐Kasthala S, Elmitt N, Moore M. How does studying rurally affect peer networks and resilience? A social network analysis of rural‐ and urban‐based students. Aust J Rural Health 2018; 26: 400‐407.

- 50. Walters L, Couper I, Stewart R, et al. The impact of interpersonal relationships on rural doctors’ clinical courage. Rural Remote Health 2021; 21: 6668.

- 51. Bourke L, Waite C, Wright J. Mentoring as a retention strategy to sustain the rural and remote health workforce. Aust J Rural Health 2014; 22: 2‐7.

- 52. Greenhill J, Fielke K, Richards J, et al. Towards an understanding of medical student resilience in longitudinal integrated clerkships: a grounded theory approach. BMC Med Educ 2015; 15: 137.

- 53. Woolley T, Larkins S, Sen Gupta T. Career choices of the first seven cohorts of JCU MBBS graduates: producing generalists for regional, rural and remote northern Australia. Rural Remote Health 2019; 19: 127‐136.

- 54. Ramani S, McKimm J, Thampy H, et al. From clinical educators to educational scholars and leaders: strategies for developing and advancing a career in health professions education. Clin Teach 2020; 17: 477‐482.

- 55. Sen Gupta T, Manahan DL, Lennox D. The Queensland Health Rural Generalist Pathway: providing a medical workforce for the bush. Rural Remote Health 2013; 13: 2319.

- 56. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. Rural health equity strategic action plan [news]. 15 Dec 2020. https://www.surgeons.org/News/News/Rural‐Health‐Equity‐Strategic‐Action‐Plan (viewed Feb 2023).

- 57. Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine. Fellowship guide. https://www.acrrm.org.au/docs/default‐source/all‐files/acrrm‐fellowship‐guide.pdf (viewed June 2023).

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Adelaide, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Adelaide agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Australian rural clinical schools are funded through the Australian Government Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training program. The funder had no role in the preparation of this article.

We all work within Australian rural clinical schools or rural medical programs and have leadership roles in rural medical undergraduate training or rural research.