Eating disorders are complex disorders characterised by persistent disturbances in eating behaviour and body weight.1,2 They affect individuals from diverse sociodemographic groups and range in complexity, severity and duration.1,3,4 Compared with those without eating disorders, individuals with these disorders have lower employment participation, higher health care and informal care costs, and lost lifetime earnings.5 Before the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, a population‐based study reported that the aggregate financial cost of eating disorders to the Australian Government was $3.2 billion in 2018.6

It has been estimated that over one million Australians are living with an eating disorder in any given year.7 The COVID‐19 pandemic saw a dramatic increase in the numbers presenting with distress associated with disordered eating in both the general population and in people previously diagnosed with an eating disorder.8,9 The past decade has seen a rapid expansion of research into eating disorder interventions, and, in 2019, in response to the increasing burden of eating disorders, the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care implemented significant policy changes to improve patient access to Medicare and inpatient care.10

This narrative review summarises recent developments in the identification and management of eating disorders and the gaps that persist in optimal management for eating disorders. We sourced evidence from contemporary international and national evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines3,11,12,13,14,15,16 along with recent systematic reviews and meta‐analyses4,5,8,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 known to the authors and/or identified through a PubMed database search. It was not possible to cite all primary publications on all topics; thus, individual research articles or other publications were selected as examples that reflect the body of literature.

Diagnosis and classification

Eating disorders are characterised by a persistent disturbance of eating, or eating‐related behaviours, that significantly impairs physical health or psychosocial functioning (Box 1).1 Although historically they have been conceptualised as disorders of low body weight, there is substantive evidence that this is inaccurate.31 This perception and weight stigma present a significant treatment barrier for individuals of higher weight in Australia31,32 and contribute to misdiagnosis and undertreatment. To begin addressing this treatment gap, the National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) recently released a clinical practice guideline for the management of eating disorders for people with higher weight.16

Anorexia nervosa is characterised as the restriction of energy intake leading to a low body weight accompanied by body image distortion and an intense fear of gaining weight.1,2 Notably, the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM‐5‐TR)1 provides no upper body mass index (BMI) limit for anorexia nervosa and the determination of “underweight” falls to clinical judgement. Individuals who meet the diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa with an adequate or high BMI, despite significant weight loss, may be given the diagnosis of atypical anorexia nervosa — a subtype of other specified feeding and eating disorder (OSFED) in the DSM‐5‐TR.1

Even though both anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa share overvaluation of weight and shape as a key diagnostic criterion, individuals with bulimia nervosa are typically not underweight. Bulimia nervosa is characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating (eating an objectively large amount of food in a short period of time) followed by active engagement in compensatory behaviours, such as vomiting, laxative use, or excessive exercise to prevent weight gain.1 These episodes may occur as little as once a week but must occur for a minimum of three months according to the DSM‐5‐TR1 or one month according to the 11th revision of the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD‐11).2

Binge eating disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) do not include body image concerns as a core diagnostic criterion.1,2 Binge eating disorder is characterised by recurrent binge eating episodes, in the absence of any compensatory behaviours, that cause marked distress at least weekly for several months.1 The DSM‐5‐TR and ICD‐11 differ in their criteria for binge eating disorder, with the DSM‐5‐TR requiring three additional descriptors.1,2 The broader ICD‐11 criteria appear more congruent with lived experience reports of binge eating disorder, allowing for the occurrence of subjective binge eating episodes, thus potentially increasing the clinical utility of the ICD‐11 compared with the DSM‐5‐TR for binge eating disorder.33,34

ARFID is characterised by the avoidance of and aversion to food and eating.1,2 Notably, this restriction is not the result of a body image disturbance but is due to anxiety or a heightened sensitivity to the sensory aspects of food. Individuals who do not meet the prescribed behavioural frequency or other criteria of the main eating disorder diagnosis may be classified as having OSFED or an unspecified feeding or eating disorder (UFED) in the DSM‐5‐TR1 and in the ICD‐11.2 OSFED includes atypical anorexia nervosa, subthreshold bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, purging disorder, and night eating syndrome.1

Epidemiology and prevalence

Attempting global and community prevalence estimates is fraught with methodological problems, such as the use of self‐report screening instruments versus standardised clinician‐ or investigator‐administered interviews, and changes in symptoms for diagnostic criteria with evolving DSM iterations. Statistics may therefore vary widely.20,21 A systematic review reported that the mean‐weighted lifetime prevalence rate of eating disorders was 8.4% (range, 3.3–18.6%) in women and 2.2% (range, 0.8–6.5%) in men21 (Box 2). The 2019 Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) estimated that the number of people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa was 13.6 million (95% uncertainty interval [UI], 10.2–17.5) and a subsequent review estimated an additional 41.9 million (95% UI, 27.9–59.0) people with binge eating disorder and OSFED.35 These estimates suggest that the total number of people with an eating disorder in 2019 was about 55.5 million (95% UI, 38.7–75.2) globally. A growing proportion of people seeking treatment for an eating disorder meet the diagnostic criteria for atypical anorexia nervosa. Although prevalence rates vary (2.5–2.9% in community samples), a systematic review reported that the point prevalence of atypical anorexia nervosa met or exceeded that of anorexia nervosa.29

Developmentally, ARFID is more likely to emerge during childhood, with the highest prevalence estimates reported in paediatric feeding clinics.29 Similarly, anorexia nervosa has its onset early in the developmental life course, but bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder typically occur later in adolescence or emerging adult years.29 Furthermore, the course of eating disorders is also varied, with crossover between eating disorders being common. For example, in treatment settings, up to 10% of patients diagnosed with anorexia nervosa (restricting type) go on to develop bulimia nervosa.36

Although eating disorders are indiscriminate and affect individuals of all ages, sexes, gender identities, ethnicities, socio‐economic backgrounds, and body types, the reported prevalence of eating disorders is higher in females and young people, but the biological sex distribution is more equal in binge eating disorder and OSFED.37 Epidemiological research indicates that physical and psychological co‐occurring conditions in people experiencing an eating disorder (eg, cardiovascular and metabolic disease or other psychiatric disorders), with or without a high body weight, are common.38,39 In addition, eating disorders are associated with elevated mortality rates, particularly anorexia nervosa, which has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder.5

Management of eating disorders overview

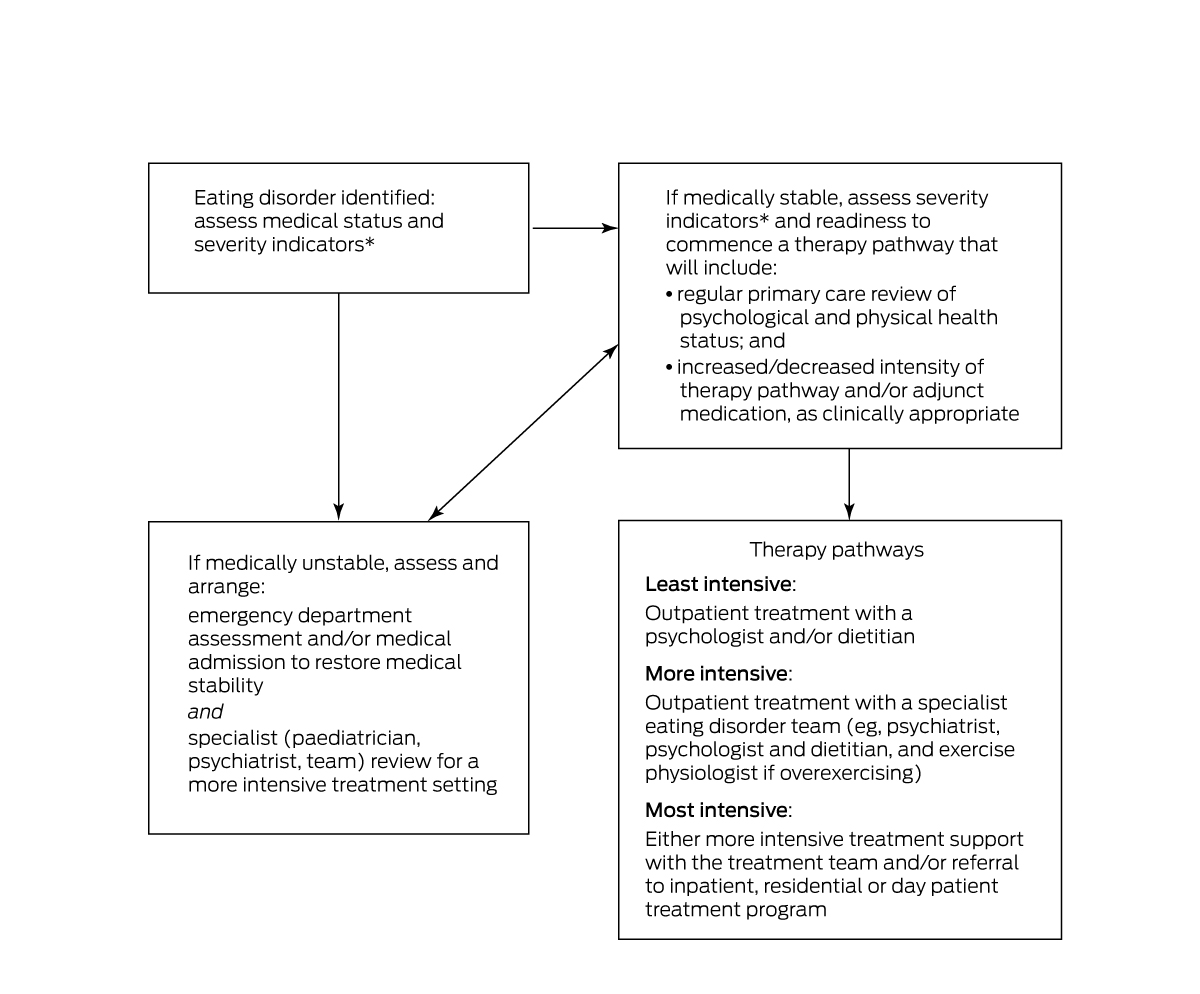

Treatment for eating disorders is typically delivered on a continuum of care, starting with outpatient treatment and moving to more intensive settings, and inpatient hospitalisation, if required, in cases of medical instability.3,11,14,23 An individual's journey is unique and dependent on numerous factors, such as treatment availability, life stage, attitudes and beliefs about treatment, symptom severity, medical stability, residential location, and financial constraints of the individual.3,11,14,23 Furthermore, recent North American clinical practice guidelines emphasise the need for person‐centred, recovery‐oriented and least restrictive care.12,13 Improving access locally, individuals with a clinical diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder or OSFED (but not ARFID, which is a notable inequity) are eligible to access up to 40 psychological treatment sessions and 20 dietetic sessions in a 12‐month period through an eating disorder treatment and management plan under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).10,40

Treatments for eating disorders typically encompass, but are not limited to, psychological, pharmacological, medical, nutritional, and physical activity interventions. As such, contemporary clinical practice guidelines recommend a multidisciplinary approach to optimise treatment outcomes.3,11,12,14,41 Thus, the implementation of an eating disorder treatment and management plan often requires health care professionals working together as a formal (physically co‐located) or virtual (online) team through interprofessional collaborative practice,41,42 with each clinician practising within their competency and scope of professional practice. The minimum interprofessional collaborative practice would comprise an eating disorder‐informed psychologist and family doctor, with more complex cases including additional interdisciplinary eating disorder specialist supports, such as a registered dietitian, a specialist physician or paediatrician, a psychiatrist, a nurse, an exercise therapist, an activity or occupational therapist, and a social worker or a family therapist.3,11,14

In 2017, the Australia National Agenda for Eating Disorders identified that 97% of health care clinicians had received insufficient training in eating disorders to enable them to provide treatment with confidence.43 In response to this, the NEDC developed a set of eating disorder core competencies as a foundation for strengthening the workforce.44 The Australia and New Zealand Academy for Eating Disorders (ANZAED) eating disorder credential now provides formal recognition of the qualifications, knowledge, training, and professional development activities required to meet the minimum standards for the delivery of safe and effective treatment for eating disorders.45

Assessment

Despite the availability of numerous screening instruments for eating disorders, all screening measures lack high levels of positive predictive power (Box 3).20,46,48,49,50,51,52 Eating disorder features and BMI may be assessed for diagnostic purposes using the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) diagnostic interview,46 which is viewed as the gold standard for eating disorder diagnosis and psychopathology, and its self‐report derivative, the 28‐item self‐report EDE Questionnaire (EDE‐Q).46 At present, the EDE‐Q is a compulsory component of the MBS for all eating disorders except for anorexia nervosa.10,53 For screening purposes, concise instruments with low respondent burden such as the five‐item SCOFF49 or the Screen for Disordered Eating (SDE)50 are preferred. The SDE also has particularly high sensitivity.50

Current status of treatments and interventions

Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies, such as transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural therapy enhanced for eating disorders (CBT‐E),46 are the first line treatment for eating disorders in adults.11,14 CBT‐E is typically delivered over 20 weekly sessions for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder and over 40 weekly sessions for anorexia nervosa.17 Family‐based treatment is the leading first line therapy for children and adolescents.11,12,13,14,15,54 This intervention may be delivered to the whole family or the parents separately.55 An alternative to family‐based treatment in children and adolescents is a form of CBT‐E that has been modified to have additional brief family sessions: cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents (CBT‐A).56 Although CBT‐A has a weaker evidence base than family‐based treatment, it shows promise in the treatment of ARFID.19,25 Similarly, adolescent focal psychotherapy may be used for younger people with anorexia nervosa.3,13,57 At present, there is no evidence to suggest that current evidence‐based treatments for eating disorders are not appropriate for people with higher weight.11,16 Box 4 presents a summary of the key elements of the main MBS‐listed40 evidence‐based psychological therapies.46,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62

A comprehensive description of psychological therapies is found in the treatment guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.11 Common to therapies specific to eating disorders are psycho‐education and facilitation of physical health care through weight monitoring and nutritional counselling and meal planning, which are typically offered by a registered dietitian. Although developed for individual outpatient care, some interventions such as CBT and dialectical behavioural therapy63 have been adapted for delivery in group sessions, which are more commonly used in hospital or other residential settings. Further treatment development is needed to address attrition in particular — a systematic review found that 50% of individuals with an eating disorder may drop out of treatment prematurely.27

Scalable therapies

There is increasing evidence for brief forms of CBT‐E (eg, ten sessions or online guided self‐help CBT) for eating disorders, particularly bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.18,64 Reviews of the efficacy of and engagement in online self‐help treatments highlight their potential to produce moderately sized reductions in core behavioural and cognitive symptoms.18,65 However, findings are mixed and more research is needed into the determinants of the observed high rates of attrition,19,65 which is a common feature in self‐help treatments generally.66 Pure self‐help, where there is no guidance, is most appropriately used as a first step in treatment while waiting to access more intensive evidence‐based treatment options.3,11,14

Pharmacological therapies

There are no medications recommended in current general guidelines as first line in the treatment of an eating disorder.3,11,12,14 Despite several small trials of second generation antipsychotics, such as olanzapine for anorexia nervosa, the results are mixed.24,25 Other psychotropic agents, such as antidepressants, currently have little direct role or evidence for treatment in anorexia nervosa, although they may be used where there is comorbid major depression.

Since the early trials of higher dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (eg, fluoxetine 60 mg daily), there have been a small number of trials of topiramate and lisdexamfetamine for binge eating disorder.14,25 Meta‐analyses support the role of second generation antidepressants and show weaker evidence and more adverse effects for topiramate in the treatment of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder.24 There is moderate evidence for efficacy of lisdexamfetamine in the treatment of binge eating disorder.24,25 However, these are not recommended as standalone treatments given the small to medium effect sizes and attrition rates that may be higher than evidence‐based psychological therapies.3,11,14

There is notably a gap in the evidence for the use of anxiolytics in any eating disorder despite the known co‐occurrence of, and shared risk (including heritability) for, anxiety disorders.12,67 Although medications such as antipsychotics and antidepressants may also reduce anxiety, specific research is needed.25

Physical health interventions

The physical consequences of eating disorders have been well documented in the medical literature and comprehensively outlined in current clinical practice guidelines.3,11,12 Evidence indicates that the severity of specific medical comorbid conditions may be similar, regardless of an individual's BMI, in either bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder.39 Similarly, the severity and risk of medical compromise in anorexia nervosa or atypical anorexia nervosa is more closely related to the amount and rapidity of weight loss and presence of purging behaviours than the individual's BMI.68 Eating disorder symptoms and their severity inform treatment, including indicators for referral to specialist services (Box 5).

The risks of the refeeding syndrome are well acknowledged in the medical literature.69 Current research supports optimising hospital care to allow more rapid weight regain protocols, and more assertive refeeding protocols have been demonstrated to be safe when combined with comprehensive medical monitoring and nutritional supplementation (eg, phosphate).69

Prognosis and outcomes

Major challenges in improving treatment outcomes are in early detection and treatment engagement, as a shorter duration of illness and early change in treatment are consistent predictors of a better outcome.4 Despite the severity of eating disorders, the average length of delay between onset of eating disorder symptoms and treatment seeking in Australia was 5.28 years in a sample of patients aged 13 years and over.64 In this study, longer delays in treatment seeking for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder compared with anorexia nervosa were proposed to be related to the more visible signs of emaciation being observed and treatment initiated by family members.

There are many factors contributing to this problem: low levels of eating disorder health literacy in the experiencing person and health professionals, help seeking for weight loss management rather than the eating disorder, stigma and shame, poor affordability, long wait times, limited access to evidence‐based interventions, and self and societal endorsement of weight loss behaviours.17,32 Latency in treatment seeking also appears to be magnified for counter‐stereotypical eating disorder presentations. For example, atypical anorexia nervosa appears to be as common as anorexia nervosa; however, research indicates that individuals with atypical anorexia nervosa are less frequently referred to specialist eating disorder services.22

Although remission rates remain variable for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, long term follow‐up studies support cautious optimism for recovery.3,5,25 A recent 22‐year follow‐up study of 228 women receiving specialist treatment for anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa found that 62.8% of those with anorexia nervosa and 68.2% of those with bulimia nervosa achieved recovery.70 Evidence for binge eating disorder is more limited but trends towards recovery for the majority.24,71

Given the relatively recent introduction of ARFID to psychiatric diagnostic schemes, sparse research has examined its treatment outcomes.22,25 Challenges regarding the diagnostic validity and boundaries between the different OSFED/UFED groups, and common crossover across diagnoses36 also make it difficult to obtain meaningful assessment of treatment outcomes. As such, less is known about the course of OSFED/UFED and ARFID.25 Transition between full‐threshold diagnostic categories may also indicate increased risk of prolonged illness duration.4

Looking to the future

Research indicates that optimal care management has yet to be realised, and it is notable that no psychological therapy has been shown to be superior to an alternative therapy in a randomised controlled trial for anorexia nervosa.24,25 Trials are needed to develop a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of what works for whom. The first residential facility in Australia, Wandi Nerida (https://wandinerida.org.au), opened in 2021, offering an alternative to hospital inpatient care. A recent systematic review of 19 studies reported positive outcomes associated with residential‐based treatments, which are notable for their purposive employment of people with lived experience, but there are no randomised controlled trials.26 Similarly, other approaches that are currently used require evidence. These include the adoption of weight‐neutral practices in people of higher weight72 and alternative psychological therapies (eg, narrative therapy).73 There is also emerging evidence to support person‐centred approaches that focus on quality of life in people with more enduring illness.28,74

There is preliminary evidence for the efficacy of psychedelics in the treatment of anorexia nervosa,75 and further research is needed to assess the feasibility, brain mechanisms, and outcomes of treating anorexia nervosa with psilocybin and other psychedelics such as ketamine.76 Research regarding the clinical utility of neuromodulation (eg, with transcranial direct current stimulation) for binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa, or electroencephalography neurofeedback for binge eating disorder, is sparse but shows promise in increasing self‐regulatory control and reducing participant self‐reported binge eating urges.71 Future studies are needed, with larger and more diverse samples, to determine specific treatment mechanisms.

Conclusion

Eating disorders are now well acknowledged mental health problems that are common and present in people from diverse sociodemographic backgrounds. There are a number of excellent clinical practice guidelines and a robust evidence base, particularly for first line care with specific psychological therapies. Medications play an important adjunct role in care, and novel neuromodulating treatments such as psychostimulants are under study. There is emerging evidence for increased person‐centred care and treatment adaptation to address rates of attrition, including alternatives to hospital inpatient programs, and more respectful consideration of care broadly for people with high weight.

Box 1 – Overview of the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM‐5‐TR) diagnostic criteria for eating disorders

|

|

Anorexia nervosa |

Bulimia nervosa |

Binge eating disorder |

ARFID* |

OSFED |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Weight and/or shape overvaluation |

Specified with fear of fatness and/or behaviour preventing weight gain |

Specified |

Not specified |

Specified not present |

Not specified |

||||||||||

|

Body weight status |

Underweight |

Not specified |

Not specified |

May be present with unmet nutritional and/or energy needs |

Not specified |

||||||||||

|

Regular binge eating |

Specified in binge eating and/or purging type |

Specified |

Specified with distress and three to five descriptors† |

Not specified |

Specified in bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder of low frequency and/or limited duration; may occur in night eating syndrome |

||||||||||

|

Regular weight control behaviours and/or compensation |

Specified in binge eating and/or purging type |

Specified: either purging or fasting and/or excessive exercise |

Not specified |

Specified not present; behaviours may be present but not for weight control |

May be present in atypical anorexia nervosa, purging disorder specified in bulimia nervosa of low frequency and/or limited duration |

||||||||||

|

Remission specifier‡ |

Partial/full |

Partial/full |

Partial/full |

In remission |

None |

||||||||||

|

Severity specifier |

BMI scale; BMI percentile in children and adolescents |

Frequency of compensation |

Frequency of binge eating |

None |

None |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

ARFID = avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; BMI = body mass index; OSFED = other specified feeding or eating disorder. * If anorexia nervosa is present, by definition, no other eating disorder will be present. If ARFID is present, by definition, anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are not present. Unspecified feeding or eating disorder has no specific criteria. † Specific descriptors in the DSM‐5‐TR include eating much more rapidly than normal; eating until feeling uncomfortably full; eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry; eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating; or feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed or very guilty afterward. ‡ If the criteria are no longer met, the specifier indicates whether the eating disorder is in partial or full remission. Source: Table adapted from Hay30 with permission from the author, as per Creative Commons Licence Attribution‐NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY‐NC 4.0; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐nc/4.0). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Global prevalence estimates of eating disorders*

|

Prevalence |

Number of studies |

Any eating disorder |

Anorexia nervosa |

Bulimia nervosa |

Binge eating disorder |

OSFED, UFED (EDNOS) |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

12 months |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Women |

|

2.2% |

0.05% |

0.7% |

1.4% |

na |

|||||||||

|

Men |

|

0.7% |

0.1% |

0.4% |

0.6% |

na |

|||||||||

|

Lifetime |

33 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Women |

|

8.4% |

1.4% |

1.9% |

2.8% |

4.3% |

|||||||||

|

Men |

|

2.2% |

0.2% |

0.6% |

1.0% |

3.6% |

|||||||||

|

Point |

73 |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Women |

|

5.7% |

2.8% |

1.5% |

2.3% |

10.1% |

|||||||||

|

Men |

|

2.2% |

0.3% |

0.1% |

0.3% |

0.9% |

|||||||||

|

GBD estimation |

na |

|

13.6 million† |

|

17.3 million |

24.6 million |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; GBD = global burden of diseases; na = not available; OSFED = other specified feeding or eating disorder; UFED = unspecified feeding or eating disorder. * Data extracted from Galmiche et al,22 and Santomauro et al.35 † Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 – Some commonly used screening and/or assessment questionnaires

|

|

Descriptor |

Utility |

Website* |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, version 6 (EDE‐Q‐6)46 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

https://insideoutinstitute.org.au/resource‐library/eating‐disorder‐examination‐questionnaire‐ede‐q |

|||||||||||||||

|

ED‐1547 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

https://c2coast.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/20191211_ED‐15‐Tool‐and‐Scoring‐Key.pdf |

|||||||||||||||

|

Binge Eating Scale48 |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

SCOFF Questionnaire49 |

|

|

https://insideoutinstitute.org.au/resource‐library/the‐scoff‐questionnaire |

||||||||||||

|

Screen for Disordered Eating (SDE)50 |

|

|

https://www.nyeatingdisorders.org/documents/Screen%20for%20Disordered%20Eating.pdf |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Viewed Feb 2023. † There are several brief (eight to 13 items) versions of the EDE‐Q measuring features over shorter time periods (eg, weekly).51 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Overview of psychological therapies listed by Medicare10,40 for the management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED)

|

|

MANTRA59 |

SSCM60 |

FPT61 |

IPT62 |

FBT/FT54 |

DBT63 |

AFT57 |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Eating disorder‐indicated evidence base for use |

Adults and older adolescents with any eating disorders (transdiagnostic) or with specific eating disorders |

Adults with anorexia nervosa |

Adults with anorexia nervosa |

Adults with anorexia nervosa |

Adults with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder |

Children and adolescents with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa |

Adults with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder |

Adolescents with anorexia nervosa (second line) |

|||||||

|

Theoretical model |

CBT formulation and in CBT‐enhanced transdiagnostic maintaining factors |

Cognitive/interpersonal |

Atheoretical |

Psychodynamic formulation |

Interpersonal function's bidirectional relationship with eating disorder symptoms mediated by self‐esteem and negative affect |

Atheoretical |

The dialectic of opposing views of eating disorder behaviours and their use in distress reduction |

Addresses deficits in development of self‐concept; derived from self‐psychology |

|||||||

|

Targets |

Dysfunctional eating, weight/shape (body dissatisfaction) beliefs, disordered eating |

Intra‐ and interpersonal maintaining factors (eg, inflexibility) |

Undernutrition, other targets as personalised goals |

Intra‐ and interpersonal maintaining factors (eg, low self‐esteem) |

Interpersonal problem areas: grief, role transitions, role disputes, interpersonal sensitivities |

Food restriction and family eating; other family/adolescent issues |

Learning skills in mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness |

Anorexia nervosa as a coping strategy for problematic developmental issues; promotion of individuation; behaviours/strategies facilitating coping skills and independence |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AFT = adolescent focused therapy for eating disorders; CBT = cognitive behavioural therapy; CBT‐A = cognitive behavioural therapy for adolescents; CBT‐AN = cognitive behavioural therapy for anorexia nervosa; CBT‐BN/BED = cognitive behavioural therapy for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder; CBT‐ED = cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders (more commonly known as CBT‐E); DBT = dialectical behavioural therapy; FBT = family‐based treatment for eating disorders; FPT = focal psychodynamic therapy; FT‐AN = family therapy for anorexia nervosa; IPT = interpersonal therapy; MANTRA = Maudsley model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults; SSCM = specialist supportive clinical management. Source: The table was adapted and updated from Hay30 with permission from the author, as per Creative Commons Licence Attribution‐NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY‐NC 4.0; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‐nc/4.0). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Indicators for eating disorder treatment pathways

* May include the use of, for example, the severity indicators for anorexia nervosa described in the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM‐5‐TR):1 mild = body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) > 17, moderate = BMI 16–16.99, severe = BMI 15–15.99, and extreme = BMI < 15; and the severity indicators for bulimia nervosa (purging frequency) and binge eating disorder (binge frequency): mild = one to three episodes per week, moderate = four to seven episodes per week, severe = eight to 13 episodes per week, and extreme = > 14 episodes per week.

This information does not replace full medical assessment and the clinical judgment of medical practitioners in relation to an individual patient presentation and reference to a clinical practice guideline for guidance (eg, Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists,3 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,11 American Psychiatric Association,12 and Couturier et al13).

The BMI should be interpreted in light of changes over time and weight loss practices. The lower the BMI and the more rapid the drop in BMI, the greater the medical risk. For children and adolescents, use appropriate BMI percentiles.

A very low body weight (severe to extreme) and/or significant purging (severe to extreme) pose a substantive risk to physical safety, and the combination of both low weight and purging has very high risk, which includes sudden death.

There are also longer term impacts of eating disorders such as, but not limited to, bone demineralisation (in low weight and/or loss of menstruation) and dental decay (from vomiting).

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Phillipa J Hay1,2

- Rebekah Rankin1

- Lucie Ramjan3

- Janet Conti1,3

- 1 Translational Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW

- 2 South Western Sydney Local Health District, Sydney, NSW

- 3 Western Sydney University, Sydney, NSW

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Western Sydney University, as part of the Wiley – Western Sydney University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Phillipa Hay has received sessional fees from the Therapeutic Guidelines publication and the Health Education and Training Institute (HETI, NSW), and royalties/honoraria from Hogrefe and Huber, McGraw Hill Education, Blackwell Scientific Publications, BioMed Central, and PLOS Medicine. She has prepared a report under contract for Takeda (formerly Shire) Pharmaceuticals regarding binge eating disorder (July 2017), and is a consultant to Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

- 1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, text revision (DSM‐5‐TR). Washington: APA, 2022.

- 2. World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th revision (ICD‐11). Geneva: WHO, 2019. https://icd.who.int/en (viewed Apr 2023).

- 3. Hay P, Chinn D, Forbes D, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2014; 48: 977‐1008.

- 4. Vall E, Wade TD. Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Eat Disord 2015; 48: 946‐971.

- 5. van Hoeken D, Hoek HW. Review of the burden of eating disorders: mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2020; 33: 521.

- 6. Tannous WK, Hay P, Girosi F, et al. The economic cost of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder: a population‐based study. Psychol Med 2022; 52: 3924‐3938.

- 7. Hay P, Mitchison D, Collado AE, et al. Burden and health‐related quality of life of eating disorders, including avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), in the Australian population. J Eat Disord 2017; 5: 21.

- 8. Linardon J, Messer M, Rodgers RF, Fuller‐Tyszkiewicz M. A systematic scoping review of research on COVID‐19 impacts on eating disorders: A critical appraisal of the evidence and recommendations for the field. Int J Eat Disord 2022; 55: 3‐38.

- 9. Phillipou A, Meyer D, Neill E, et al. Eating and exercise behaviors in eating disorders and the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. Int J Eat Disord 2020; 53: 1158‐1165.

- 10. Hay P. A new era in service provision for people with eating disorders in Australia: 2019 Medicare Benefit Schedule items and the role of psychiatrists. Australas Psychiatry 2020; 28: 125‐127.

- 11. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Eating disorders: recognition and treatment full guideline. NICE, 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng69/evidence/full‐guideline‐pdf‐161214767896 (viewed Feb 2023).

- 12. Crone C, Fochtmann LJ, Attia E, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2023; 180: 167‐171

- 13. Couturier J, Isserlin L, Norris M, et al. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2020; 8: 1‐80.

- 14. Hilbert A, Hoek HW, Schmidt R. Evidence‐based clinical guidelines for eating disorders: international comparison. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017; 30: 423‐437.

- 15. Resmark G, Herpertz S, Herpertz‐Dahlmann B, Zeeck A. Treatment of anorexia nervosa — new evidence‐based guidelines. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 153.

- 16. Ralph AF, Brennan L, Byrne S, et al. Management of eating disorders for people with higher weight: clinical practice guideline. J Eat Disord 2022; 10: 121.

- 17. Atwood ME, Friedman A. A systematic review of enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT‐E) for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2020; 53: 311‐330.

- 18. Barakat S, Maguire S, Smith KE, et al. Evaluating the role of digital intervention design in treatment outcomes and adherence to eTherapy programs for eating disorders: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Eat Disord 2019; 52: 1077‐1094

- 19. Bourne L, Bryant‐Waugh R, Cook J, Mandy W. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a systematic scoping review of the current literature. Psychiatry Res 2020; 288: 112961.

- 20. Bryant E, Spielman K, Le A, et al. Screening, assessment and diagnosis in the eating disorders: findings from a rapid review. J Eat Disord 2022; 10: 78.

- 21. Galmiche M, Déchelotte P, Lambert G, Tavolacci MP. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Nutr 2019; 109: 1402‐1413.

- 22. Harrop EN, Mensinger JL, Moore M, Lindhorst T. Restrictive eating disorders in higher weight persons: A systematic review of atypical anorexia nervosa prevalence and consecutive admission literature. Int J Eat Disord 2021; 54: 1328‐1357.

- 23. Hay PJ, Touyz S, Claudino AM, et al. Inpatient versus outpatient care, partial hospitalisation and waiting list for people with eating disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019; (1): CD010827.

- 24. Hilbert A, Petroff D, Herpertz S, et al. Meta‐analysis of the efficacy of psychological and medical treatments for binge‐eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019; 87: 91‐105.

- 25. Monteleone AM, Pellegrino F, Croatto G, et al. Treatment of eating disorders: a systematic meta‐review of meta‐analyses and network meta‐analyses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022; 142: 104857.

- 26. Peckmezian T, Paxton SJ. A systematic review of outcomes following residential treatment for eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2020; 28: 246‐259.

- 27. Vinchenzo C, McCombie C, Lawrence V. The experience of patient dropout from eating disorders treatment: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. BJPsych Open 2021; 7 (Suppl): S299.

- 28. Zhu J, Yang Y, Touyz S, et al. Psychological treatments for people with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: a mini review. Front Psychiatry 2020; 11: 206.

- 29. Hay P, Aouad P, Le A, et al. Epidemiology of eating disorders: population, prevalence, disease burden and quality of life informing public policy in Australia — a rapid review. J Eat Disord 2023; 11: 23.

- 30. Hay P. Current approach to eating disorders: a clinical update. Intern Med J 2020; 50: 24‐29.

- 31. Da Luz FQ, Sainsbury A, Mannan H, et al. Prevalence of obesity and comorbid eating disorder behaviors in South Australia from 1995 to 2015. Int J Obes 2017; 41: 1148‐1153.

- 32. Hart LM, Mitchison D, Hay PJ. The case for a national survey of eating disorders in Australia. J Eat Disord 2018; 6: 30.

- 33. Palavras M A, Hay P, Claudino A. An investigation of the clinical utility of the proposed ICD‐11 and DSM‐5 diagnostic schemes for eating disorders characterized by recurrent binge eating in people with a high BMI. Nutrients 2018; 10: 1751.

- 34. Claudino AM, Pike KM, Hay P, et al. The classification of feeding and eating disorders in the ICD‐11: results of a field study comparing proposed ICD‐11 guidelines with existing ICD‐10 guidelines. BMC Medicine 2019; 17: 93.

- 35. Santomauro DF, Melen S, Mitchison D, et al. The hidden burden of eating disorders: an extension of estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8: 320‐328.

- 36. Eddy KT, Dorer DJ, Franko DL, et al. Diagnostic crossover in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: implications for DSM‐V. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165: 245‐250.

- 37. Ward ZJ, Rodriguez P, Wright DR, et al. Estimation of eating disorders prevalence by age and associations with mortality in a simulated nationally representative US cohort. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2: e1912925.

- 38. Momen NC, Plana‐Ripoll O, Yilmaz Z, et al. Comorbidity between eating disorders and psychiatric disorders. Int J Eat Disord 2022; 55: 505‐517.

- 39. Appolinario JC, Sichieri R, Lopes CS, et al. Correlates and impact of DSM‐5 binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa and recurrent binge eating: a representative population survey in a middle‐income country. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2022; 57: 1491‐1503.

- 40. Services Australia. Eating disorder treatment and management plans [website]. Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/education‐guide‐eating‐disorder‐treatment‐and‐management‐plans (viewed Feb 2023).

- 41. Heruc G, Hurst K, Casey A, et al. ANZAED eating disorder treatment principles and general clinical practice and training standards. J Eat Disord 2020; 8: 63.

- 42. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. WHO, 2010. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework‐for‐action‐on‐interprofessional‐education‐collaborative‐practice (viewed Feb 2023).

- 43. Butterfly Foundation. The national agenda for eating disorders 2017 to 2022: establishing a baseline of evidence‐based care for any Australian with or at risk of an eating disorder. Sydney: Butterfly Foundation, 2018. https://butterfly.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2020/05/National‐Agenda‐for‐Eating‐Disorders‐2018.pdf (viewed Feb 2023).

- 44. National Eating Disorders Collaboration. National practice standards for eating disorders. Sydney: NEDC, 2018. www.nedc.com.au/assets/NEDC‐Resources/national‐practice‐standards‐for‐eating‐disorders.pdf (viewed Feb 2023).

- 45. Hurst K, Heruc G, Thornton C, et al. ANZAED practice and training standards for mental health professionals providing eating disorder treatment. J Eat Disord 2020; 8: 77.

- 46. Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press, 2008.

- 47. Rodrigues T, Vaz AR, Silva C, et al. Eating Disorder‐15 (ED‐15): factor structure, psychometric properties, and clinical validation. Eur Eat Disord Rev 2019; 27: 682‐691.

- 48. Gormally JI, Black S, Daston S, Rardin D. The assessment of binge eating severity among obese persons. Addict Behav 1982; 7: 47‐55.

- 49. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999; 319: 1467‐1468.

- 50. Maguen S, Hebenstreit C, Li Y, et al. Screen for disordered eating: improving the accuracy of eating disorder screening in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2018; 50: 20‐25.

- 51. Hay P, Hart LM, Wade TD. Beyond screening in primary practice settings: time to stop fiddling while Rome is burning. Int J Eat Disord 2022; 55: 1194‐1201.

- 52. Tatham M, Turner H, Mountford VA, et al. Development, psychometric properties and preliminary clinical validation of a brief, session‐by‐session measure of eating disorder cognitions and behaviors: the ED‐15. Int J Eat Disord 2015; 48: 1005‐1015.

- 53. Wade T, Pennesi JL, Zhou Y. Ascertaining an efficient eligibility cut‐off for extended Medicare items for eating disorders. Australas Psychiatry 2021; 29: 519‐522.

- 54. Lock J, Le Grange D. Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: a family‐based approach, 2nd ed. New York and London: Guilford Press, 2015.

- 55. Le Grange D, Hughes EK, Court A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of parent‐focused treatment and family‐based treatment for adolescent anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016; 55: 683‐692.

- 56. Dalle Grave R and Caluci S. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adolescents with eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press, 2020.

- 57. Fitzpatrick KK, Moye A, Hoste R, et al. Adolescent focused psychotherapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Contemp Psychother 2010; 40: 31‐39.

- 58. Pike KM, Carter JC, Olmsted MP. Cognitive‐behavioral therapy for anorexia nervosa. In: Grilo CM, Mitchell JA; editors. The treatment of eating disorders: a clinical handbook. New York: Guilford Press, 2010; pp. 83‐107.

- 59. Schmidt U, Wade TD, Treasure J. The Maudsley model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults (MANTRA): development, key features, and preliminary evidence. J Cogn Psychother 2014; 28: 48‐71.

- 60. McIntosh VV, Jordan J, Luty SE, et al. Specialist supportive clinical management for anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2006; 39: 625‐632.

- 61. Friederich HC, Wild B, Zipfel S, et al. Anorexia nervosa: focal psychodynamic psychotherapy. Boston (MA): Hogrefe Publishing, 2019.

- 62. Tanofsky‐Kraff M, Wilfley DE. Interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of eating disorders. In: Agras WS; editor. The Oxford handbook of eating disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010; pp. 348‐372.

- 63. Wisniewski L, Warren M, Heiden M. Dialectical behaviour therapy in the treatment of eating disorders. In: Paxton S, Hay PJ; editors. Interventions for body image and eating disorders: evidence and practice. Melbourne: IP Communications, 2009; pp. 234‐250.

- 64. Hamilton A, Mitchison D, Basten C, et al. Understanding treatment delay: perceived barriers preventing treatment‐seeking for eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2022; 56: 248‐259.

- 65. Machado PPP, Rodrigues TF. Treatment delivery strategies for eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2019; 32: 498‐503.

- 66. Hermes ED, Merrel J, Clayton A, et al. Computer‐based self‐help therapy: a qualitative analysis of attrition. Health Informatics J 2019; 25: 41‐50.

- 67. Levine MP, Sadeh‐Sharvit S. Preventing eating disorders and disordered eating in genetically vulnerable, high‐risk families. Int J Eat Disord 2023; 56: 523‐534.

- 68. Whitelaw M, Lee KJ, Gilbertson H, Sawyer SM. Predictors of complications in anorexia nervosa and atypical anorexia nervosa: degree of underweight or extent and recency of weight loss? J Adolesc Health 2018; 63: 717‐723.

- 69. Garber AK, Sawyer SM, Golden NH, et al. A systematic review of approaches to refeeding in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2016; 49: 293‐310.

- 70. Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, et al. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22‐year follow‐up. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78: 17085.

- 71. Giel KE, Bulik CM, Fernandez‐Aranda F, et al. Binge eating disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022; 8: 16.

- 72. Dugmore JA, Winten CG, Niven HE, Bauer J. Effects of weight‐neutral approaches compared with traditional weight‐loss approaches on behavioral, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nutr Rev 2020; 78: 39‐55.

- 73. Conti J, Heywood L, Hay P, et al. Paper 2: a systematic review of narrative therapy treatment outcomes for eating disorders — bridging the divide between practice‐based evidence and evidence‐based practice. J Eat Disord 2022; 10: 138.

- 74. Wonderlich SA, Bulik CM, Schmidt U, et al. Severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: Update and observations about the current clinical reality. Int J Eat Disord 2020; 53: 1303‐1312.

- 75. Rodan SC, Aouad P, McGregor IS, Maguire S. Psilocybin as a novel pharmacotherapy for treatment‐refractory anorexia nervosa. OBM Neurobiology 2021; 5: 102.

- 76. Spriggs MJ, Douglass HM, Park RJ, et al. Study protocol for “psilocybin as a treatment for anorexia nervosa: a pilot study”. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 735523.

Summary