Perhaps the most basic measure of societal progress is that our children will be better off than their parents, building a thriving, more equitable and sustainable Australia for future generations. Today, it seems we are failing in this basic measure of societal achievement.

Despite many gains, such as increased immunisation rates1 and educational attainment,2 inequities have increased steadily in Australia over the past two decades3,4 and children and young people are faring poorly across core metrics. For example, one in six children live in poverty,5 one in four experience overweight or obesity,6 three in five adults report experiencing some form of child maltreatment,7 one in two adolescents are very or extremely worried about climate change,8 and one in seven children and adolescents have a mental disorder.9 For children and young people in priority populations (eg, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin or low income households), health and wellbeing outcomes are often far worse.10

As a wealthy nation, we have the tools to redirect the current trajectory for children and young people and ensure we create a thriving, sustainable and equitable society. However, turning this around will require considerable societal focus, political will and policy effort. Measuring what matters to children and young people needs to be placed at the heart of policy decision making, with government commitment to regular reporting and with clear accountability mechanisms.

This inaugural MJA supplement proposes a path forward for Australia to create policy environments that centre on the health and wellbeing of our children and young people and future generations. This requires systemic policy change. It means thinking about upstream root causes, such as the social determinants of health (eg, commercial, structural, political and economic determinants), prevention, and pre‐distribution of spending (rather than redistribution), and should involve young people and children's voices in decision making.11,12 This necessitates an economy that works for the people and the planet13 — where children's and young people's health and wellbeing are considered the real and measurable profit to the current and future economy.

The Future Healthy Countdown 2030 (the Countdown) aims to spotlight the health and wellbeing of children and young people by:- measuring and monitoring progress on critical indicators in the lead‐up to 2030;

- galvanising policy and public action, while providing accountability for essential improvements on critical indicators;

- showcasing the best available evidence that can be actioned to affect core measures; and

- spotlighting current policy priorities that need urgent attention.

Why do we need the Countdown?

Like many high income countries, decades of an economy focused on growth at all costs, rather than sustainable and equitable growth, has threatened the health and wellbeing of children and young people and future generations.14,15 It has also contributed to a culmination of “wicked problems” — those complex social and cultural problems that are interconnected and difficult to solve. Examples of such problems include the climate emergency, obesity, gross inequities and a mental health crisis, all of which disproportionately affect our children and young people, particularly those in priority groups.3,10

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic shone a light on Australia's inequities,16 with children and young people faring poorly and emerging as a strong policy interest.17 It is now critical to maintain this interest and consider how best to manage these complex issues with a sense of urgency. Australia also has many strengths (eg, high quality existing service and prevention systems), making it poised to turn things around, particularly through policy environments.

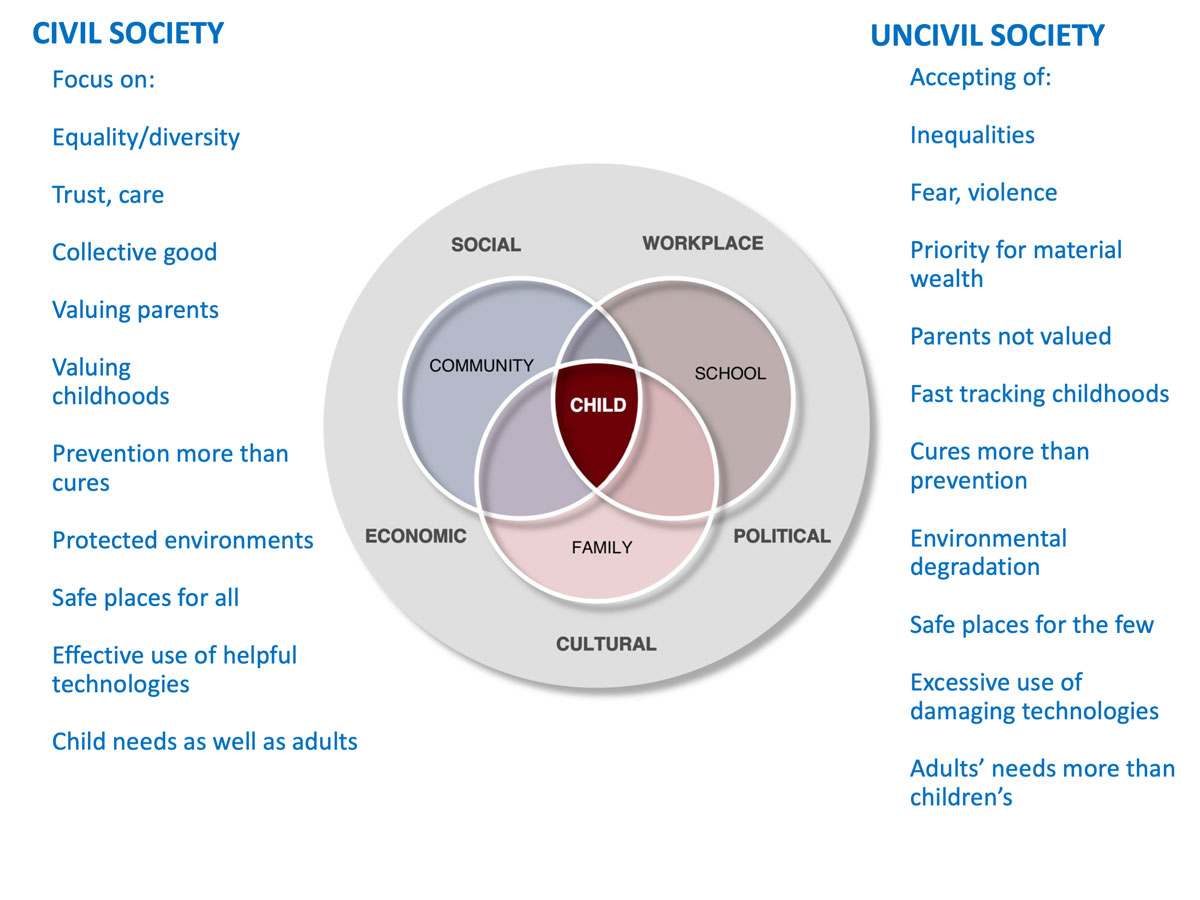

Policies for children and young people often focus on their closest environments — family, school and community — and these are key to ensuring children can thrive. But the effects of policies within a wider circle of environmental influences — workplaces, societal, economic, political and cultural — also have an impact on their lives (Box 1).18,19 As outlined by Stanley and colleagues19 almost two decades ago, these influences are outside the control of families and schools, yet they can enable or disable healthy futures by creating a civil or uncivil society (Box 1). A key example has been our failure to prioritise preventive health spending, which comprised a mere 2% of health expenditure in 2019 and saw Australia rank 30 out of 40 on the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) league table of countries.20

The Countdown will report on the most important health and wellbeing outcomes for children and young Australians — those where change could make a real difference in their lives by 2030, laying down the stepping stones for a better future. We will track progress towards these outcomes as a way of holding us all, particularly policy makers and governments at all levels, to account on these metrics. We plan to do this every year through publication in the MJA and through our collective voice and advocacy, pushing us all to go beyond the rhetoric.

Current national leadership and initiatives for children and young people

Australia has invested substantially in measuring and tracking the health and wellbeing of children and young people. For example, over 13 outstanding Australian child and young people wellbeing frameworks already exist, such as the Australian Children's Wellbeing Index, UNICEF/Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth (ARACY),10 and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Children's Headline Indicators.21 These frameworks measure outcomes across a wide range of domains that reflect key health, social, cultural and environmental aspects of young Australian lives. They have been important for spotlighting children and young people's health and wellbeing, with some gathering sporadic political traction. However, it has been challenging to get buy‐in from policy makers, financial investment and the general public. A major reason for this has been a lack of national coordination of children's policy and the fact that children's and young people's health and wellbeing are not a national priority.

Policy developments in recent years have begun to emphasise the health, wellbeing and development of children and young people. The federal government has made a commitment to “leaving no‐one behind” through the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,22 the National Children's Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy,23 the Early Years Strategy,24 Measuring What Matters as part of Australia's First Wellbeing Framework,25 Australia's Youth Policy Framework26 and Youth Advisory Groups established by the Office for Youth.27

The Uluru Statement from the Heart28 provides a clear agenda for health and other policies that would help deal with the ongoing intergenerational effects of colonisation that continue to affect children's and young people's health, education and social wellbeing.29,30 When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are empowered to make decisions about their community's health and wellbeing, this can have a profound impact.31 A constructive national dialogue and a new path must be forged to help ensure that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices are heard and that we close the gap.

Similarly, the national Measuring What Matters Wellbeing Framework25 represents a major step in the right direction and includes some key child‐ and youth‐centred measures, with a special focus on the early years. However, in its current form it does not provide any mechanism for government accountability. The Countdown will complement the government framework and contribute clear accountability measures tailored to improve policy and funding to achieve better outcomes for children and young people.

National action plans or strategies, frameworks, taskforces, seminal reports and well intended policies will ultimately fail unless they are implemented through systemic policy change and a long term vision to bring about equity and intergenerational advancement.32 Policy making is highly dependent on how Australia's short policy and political cycles can respond to significant policy and societal challenges. This requires advocacy, expert knowledge and public awareness to be harnessed to achieve political will and commitment along with legislative initiative, bipartisan support and a national commitment to monitoring, evaluation and reporting. Only with a committed longer term lens can we avoid the collapse of well intended polices at the end of each political cycle.

These issues are by no means isolated to Australia. Other countries have begun to address them systematically and we can learn from these examples. The Nordic countries have done this well for decades, with policies aimed at creating fair societies.33 Subsequently, the Nordic countries have some of the lowest rates of children living in poverty compared with other OECD countries.34 More recently, Wales implemented a novel legislative mechanism where intergenerational impacts form part of budgeting and policy decisions.35 Meanwhile, other Wellbeing Economy Governments, such as New Zealand and Scotland, have committed to using child wellbeing measures as part of budgeting reporting and recognising intergenerational effects.36,37,38

European countries have also recently agreed to a “child guarantee” to prevent and combat social exclusion by guaranteeing effective access of children in need to a set of key services (eg, free early childhood education and care, free health care, and adequate housing).39 What all of these examples include is clear government accountability for the health and wellbeing of children and young people and, in some cases, future generations (ie, the Future Generations Commissioner in Wales). In Australia, we currently lack coordination and accountability for children's and young people's policy, with it being widely dispersed across portfolios and jurisdictions.

Major existing frameworks and how they inform the Countdown

The Countdown aims to build on and draw attention to existing work. Within Australia, there has already been tremendous progress to understand what matters to children and young people. From our review of the peer reviewed and grey literature, together with our networks, we identified existing frameworks that reflect the breadth of national and state and territory efforts in articulating priority outcome areas for children and/or young people.

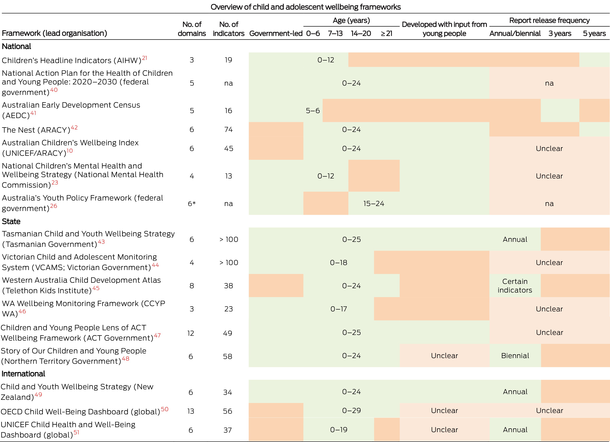

Specifically, we were interested in current frameworks that comprise multiple domains of child or youth wellbeing, or that establish multiple priority areas for policy. We also sought to include an international perspective for comparison. This led to mapping 16 highly regarded established frameworks that measure the health, wellbeing and development of children and young people, comprising seven national10,21,23,26,40,41,42 and six state‐based Australian frameworks43,44,45,46,47,48 and three major international frameworks.49,50,51 We then conducted a literature review to examine their developmental age span, number of domains, outcomes and indicator measures, reporting period, accountability mechanisms, and if they were developed with input from children and young people.

A high level summary of the literature review is presented in Box 2. Each framework is also detailed in the Supporting Information, appendix A, and a full list of framework domains and indicator measures is included in the Supporting Information, appendix B. The quality, expertise and evidence base of each framework were considered, with each providing key elements relevant to our purpose. Particular issues identified in the literature review that are central to our aims for the Countdown are outlined below.

First, age coverage was often separated between child or adolescent frameworks, with just over half of the frameworks covering the full developmental age span from birth to young adulthood. Investments targeted at early childhood development (age 0–8 years) have been long understood to improve outcomes later in life.52 Similarly, investment in adolescents and young adults (age 10–24 years) is critical and yields a triple dividend of benefits.53 As the late Professor George Patton so perfectly articulated, by investing in this age group “you change not only the present lives of young people, but also their future adult health trajectories and the welfare of the children their generation will go on to parent”.54 Many frameworks, policies and services take a child legislative approach up to the age of 18 years only. But young adulthood is a major transition period incorporating change, exploration and risk taking55 and where mental disorders can emerge or compound.56 Thus, any attempt to measure what matters to children and young people must consider the full developmental spectrum from ages 0 to 24 years.57

Second, only half of the frameworks were developed with the involvement of young people. Children and young people are experts in their own lives;58 they can offer rich, contemporary perspectives on their own experiences, wellbeing and worries, as well as unique solutions.59 This also matters from a rights perspective, where, under Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, children have a right to be heard, to have their views respected and to have a say on issues concerning them, particularly where adults are making decisions that affect them.60 Tasmania's Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy43 provides an example of how children and young people's voices can shape policy priorities and investments, and the Victorian Department of Education's Amplify toolkit illustrates how student voices can have positive impacts on school culture and student outcomes.61,62

Third, the review revealed that the six domains (valued, loved and safe; material basics; healthy; learning; participating; and positive sense of identity and culture) that form the Nest,42 a wellbeing framework developed by ARACY in 2012, were commonly used across the frameworks. These domains have been adopted by UNICEF in the Australian Children's Wellbeing Index,10 by the Tasmanian Government in their Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy,43 and the Northern Territory Government in their Story of our Children and Young People.48 The constructs are also closely mirrored by the six domains of the New Zealand Government's 2019 Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy.49 It is unsurprising that the Nest framework has been adopted widely, given that it was developed considering the voices of more than 4000 children, families and experts.63 A comprehensive refresh of the Nest, incorporating a new generation of child and youth voices, is anticipated in 2024.

Fourth, the volume of indicators used in the frameworks ranged from 16 to over 100, with most focusing on measuring deficits rather than taking a strengths‐based approach. Ignoring positive outcomes puts us at risk of not understanding the complete picture of what shapes health and wellbeing at the population level.64 Recognising the social, psychological and environmental influences that facilitate positive health and wellbeing has been shown to have a comparable impact on health as a focus on risk factors.64 Thus, considering both positive and negative outcomes is required if we are to nurture the health, development and wellbeing of all children and young people.

Finally, we examined accountability mechanisms and the frequency with which frameworks are able to report on progress towards outcomes. Framework reports varied greatly, with very few indicators being measured annually, biennially or triennially, and often data were only collected every five to 14 years (eg, in the Census and the Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing).65 This makes tracking progress extremely challenging and does not enable or promote accountability for progress.

The ARACY Nest Framework42 is most aligned with our aims for the Countdown's framework. The key elements informing this decision were its holistic nature, its coverage of the full age spectrum of children and young people (0–24 years) and that it was developed with the participation of children and young people. The Framework has now been presented in three report cards by ARACY and twice by the Australian Children's Wellbeing Index (UNICEF/ARACY), with the latter's most recent release in March 2023.10 This Index is an obvious starting point for the Future Healthy Countdown 2030. However, an additional domain that is increasingly significant for the future health and wellbeing of children and young people is the environment and sustainability.66 Accordingly, the Future Healthy Countdown comprises the six domains of the Nest framework, with the seventh domain “Environments and sustainable futures” (Box 3).

The 2030 Future Healthy Countdown

The Countdown will be a vehicle to drive public awareness and strengthen advocacy towards a healthy future for today's children and young people and for the next generations. It is designed to be a high level policy and advocacy tool that can be used to ensure children's and young people's wellbeing is front and centre in policy decisions over the next seven years.

In this first inaugural Future Healthy Countdown 2030 supplement, we asked Australia's experts across child and youth health and wellbeing to canvass each of the seven domains used in the Countdown framework. They were asked to propose key indicators for progress in these domains for all children and young people and, most importantly, for children in Australia who are the most vulnerable to poor outcomes. We plan to publish a refined set of Countdown indicators with more in‐depth analysis of each domain in 2024.

The Countdown brings together experts from a range of disciplines across the traditional silos of child and adolescent research and policy work. Further development of the Countdown indicators and annual reports will be enriched by increased diversity of leadership from a broader range of disciplines, sectors and priority population groups relevant to the future health and wellbeing of children and young people, including the input of children and young people themselves. Recognising young people as experts in their lives and concerns is central to this collaborative work. Future Countdown supplements and annual reporting will be framed by the concerns and aspirations of children and young people through qualitative data analysis each year — the Countdown is intended to enable their voices to provide a powerful narrative for change.

The next seven perspective articles in this supplement present each domain that comprises the Countdown and the outcomes that most critically affect children and young people's health and wellbeing.

Authors define and describe each domain by:- outlining the most pressing issues for children and young people within the domain and why change in the trajectory of these outcomes is critical;

- canvassing current indicator measures that are available, or highlighting a lack of measurement data, especially for priority groups (eg, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander); and

- providing baseline data on one to three key indicator measures, if these are available.

During the coming year, we will develop a concise set of core Countdown indicators encompassing these domains to track progress on the indicators of change that demonstrate a real difference to the lives of children and young people by 2030. We intend to present the Countdown's core indicators in a 2024 supplement in the MJA and report against them each year as we count down to 2030.

A simple, concise set of measures is critical for policy makers to prioritise budgetary decisions that have public support. There are strong frameworks and vast research evidence to support prioritising effective policy action for Australia's children and young people, to protect and support at‐risk and vulnerable children and benefit future generations. Policy action requires both public interest and accountability mechanisms at the whole‐of‐government level, just like core economic metrics. Accountability lies with us all, but, in particular, accountability means holding those with power to protect and improve the circumstances of children and young people to account (eg, policy makers, government and commercial and other societal institutions). The Future Healthy Countdown aims to do this.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has shown us that almost anything is possible, so if not now, then when? It is no longer acceptable to simply observe the inequities facing children and young people in Australia. We must capture the current interest, policy landscape and political will to address the “wicked problems” facing Australian children, young people and future generations to ensure they have opportunity to thrive in a sustainable and equitable Australia, for all of us.

Box 1 – Societal factors that promote a civil society for children and young people19

Source: reproduced with permission from Stanley et al.19

Box 2 – High level summary of Australian and international child and adolescent wellbeing frameworks

ACT = Australian Capital Territory; AIHW = Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; ARACY = Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth; CCYP = Commissioner for Children and Young People; na = not applicable; OECD = Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development; UNICEF = United Nations Children's Fund. * Six priority areas. The colours indicate whether the framework includes the reviewed element: green = yes; dark orange = no; light orange = unclear.

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Department of Health and Aged Care. Historical coverage data tables for all children [website]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/immunisation‐data/childhood‐immunisation‐coverage/historical‐coverage‐data‐tables‐for‐all‐children (viewed May 2023).

- 2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Attainment of Year 12 or equivalent, table 18 (time series) [website]. Canberra: ABS, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education‐and‐work‐australia/latest‐release (viewed Mar 2023).

- 3. Public Health Information Development Unit, Torrens University Australia. Inequality graphs: time series [website]. Torrens University Australia, 2023. https://phidu.torrens.edu.au/social‐health‐atlases/graphs/monitoring‐inequality‐in‐australia/whole‐population/inequality‐graphs‐time‐series#child‐and‐youth‐health (viewed May 2023).

- 4. Grudnoff M. Gini out of the bottle. Canberra: The Australia Institute, 2018. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2020/12/P434‐Gini‐out‐of‐the‐bottle‐Inequality‐in‐Australia‐is‐getting‐worse‐2018.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 5. Davidson P, Bradbury B, Wong M. Poverty in Australia 2022: a snapshot. Sydney: Australian Council of Social Service and University of New South Wales, 2022. https://povertyandinequality.acoss.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2022/10/Poverty‐in‐Australia‐2020_A‐snapshot.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia's children [Cat. No. CWS 69]. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/6af928d6‐692e‐4449‐b915‐cf2ca946982f/aihw‐cws‐69‐print‐report.pdf?inline=true (viewed Mar 2023).

- 7. Higgins DJ, Mathews B, Pacella R, et al. The prevalence and nature of multi‐type child maltreatment in Australia. Med J Aust 2023; 218: S19‐S25. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.5694/mja2.51868

- 8. Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, et al. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet Health 2021; 5: e863‐e873.

- 9. Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, et al. The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: Department of Health, 2015. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/11/the‐mental‐health‐of‐children‐and‐adolescents_0.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 10. Noble K, Rehill P, Sollis K, et al. The wellbeing of Australia's children. ARACY and UNICEF Australia, 2023. https://assets‐us‐01.kc‐usercontent.com/99f113b4‐e5f7‐00d2‐23c0‐c83ca2e4cfa2/7157d4c1‐214f‐4539‐8fd7‐eedb9876b6a8/Australian‐Childrens‐Wellbeing‐Index‐Report_2023_for%20print.pdf (viewed Apr 2023).

- 11. Trebeck K. The four P's of economic system change. Dumbo Feather 2022; 23 Apr. https://www.dumbofeather.com/articles/the‐four‐ps‐of‐economic‐system‐change/#:~:text=Similarly%2C%20as%20we%20seek%20to,Predistribution%2C%20and%20People%2Dpowered (viewed Sept 2023).

- 12. Abrar R. Building the transition together: WEAll's perspective on creating a wellbeing economy. In: Laurent É; editor. The well‐being transition: analysis and policy. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2021; pp. 157‐180.

- 13. Trebeck K, Williams J. The economics of arrival: ideas for a grown‐up economy, 1st ed. Bristol: Bristol University Press, 2019.

- 14. Gilmore AB, Fabbri A, Baum F, et al. Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. Lancet 2023; 401: 1194‐1213.

- 15. Gaukroger C, Ampofo A, Kitt F, et al. Redefining progress. Global lessons for an Australian approach to wellbeing. Centre for Policy Development, 2022. https://cpd.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2022/08/CPD‐Redefining‐Progress‐FINAL.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 16. Richardson D, Grudnoff M. Inequality on steroids: the distribution of economic growth in Australia. Canberra: The Australia Institute, 2023. https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp‐content/uploads/2023/04/Inequality‐on‐Steroids‐Who‐Benefits‐From‐Economic‐Growth‐in‐Australia‐WEB511‐copy.pdf (viewed June 2023).

- 17. Goldfeld S, O'Connor E, Sung V, et al. Potential indirect impacts of the COVID‐19 pandemic on children: a narrative review using a community child health lens. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 364‐372. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2022/216/7/potential‐indirect‐impacts‐covid‐19‐pandemic‐children‐narrative‐review‐using

- 18. Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist 1977; 32: 513.

- 19. Stanley F, Richardson S, Prior M. Children of the lucky country? How Australian society has turned its back on children and why children matter. Sydney: Pan Macmillan Australia, 2005.

- 20. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. Health expenditure and financing [website]. OECD, 2023. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA (viewed Mar 2023).

- 21. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Children's Headline Indicators [website]. Canberra: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children‐youth/childrens‐headline‐indicators/contents/overview (viewed Mar 2023).

- 22. Australian Government. Report on the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2018. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/sdg‐voluntary‐national‐review.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 23. National Mental Health Commission. The National Children's Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/getmedia/5b7112be‐6402‐4b23‐919d‐8fb9b6027506/National‐Children%E2%80%99s‐Mental‐Health‐and‐Wellbeing‐Strategy‐%E2%80%93‐Report (viewed Mar 2023).

- 24. Department of Social Services. Early Years Strategy [website]. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://www.dss.gov.au/families‐and‐children‐programs‐services/early‐years‐strategy (viewed Sept 2023).

- 25. Treasury, Australian Government. Measuring What Matters: Australia's First Wellbeing Framework. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2023. https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023‐07/measuring‐what‐matters‐statement020230721_0.pdf (viewed Aug 2023).

- 26. Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Australia's Youth Policy Framework. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2021. https://apo.org.au/node/314287 (viewed Mar 2023).

- 27. Aly A, Bowen C, Burney L, et al. Albanese Government empowering young Australians [media release]. Canberra: Ministers of the Education Portfolio, 2023. https://ministers.education.gov.au/aly/albanese‐government‐empowering‐young‐australians (viewed Sept 2023).

- 28. First Nations National Constitutional Convention. Uluru statement from the heart. Alice Springs: Central Land Council Library, 2017. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj‐484035616/view (viewed Oct 2023).

- 29. O'Neill L, Fraser T, Kitchenham A, McDonald V. Hidden burdens: a review of intergenerational, historical and complex trauma, implications for Indigenous families. J Child Adolesc Trauma 2018; 11: 173‐186.

- 30. Griffiths K, Coleman C, Lee V, Madden R. How colonisation determines social justice and Indigenous health — a review of the literature. J Pop Res 2016; 33: 9‐30.

- 31. Stanley F, Langton M, Ward J, et al. Australian First Nations response to the pandemic: a dramatic reversal of the “gap”. J Paediatr Child Health 2021; 57: 1853‐1856.

- 32. Hogan M, Hatfield‐Dodds L, Barnes L, Struthers K. Joint project on Systems Leadership for Child and Youth Wellbeing: stage 1 synthesis report. Every Child and Australia and New Zealand School of Government, 2021. https://www.everychild.co/systems_leadership_for_child_wellbeing (viewed Mar 2023).

- 33. Scott A, Campbell R. The Nordic Edge: policy possibilities for Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 2021.

- 34. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. CO2.2: Child poverty. OECD, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/els/CO_2_2_Child_Poverty.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 35. Future Generations Commissioner for Wales. Well‐being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. https://www.futuregenerations.wales/about‐us/future‐generations‐act/ (viewed Feb 2023).

- 36. Wellbeing Economy Alliance. Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo). https://weall.org/wego (viewed Feb 2023).

- 37. Treasury, Government of New Zealand. Wellbeing Budget 2022: a secure future. Government of New Zealand, 2022. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2022‐05/b22‐wellbeing‐budget.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 38. Scottish Government. Scottish Budget: 2023–24. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2022. https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/corporate‐report/2022/12/scottish‐budget‐2023‐24/documents/scottish‐budget‐2023‐24/scottish‐budget‐2023‐24/govscot%3Adocument/scottish‐budget‐2023‐24.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 39. Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. European Child Guarantee [website]. European Commission, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1428&langId=en (viewed Sept 2023).

- 40. Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care. National Action Plan for the Health of Children and Young People 2020–2030. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2019. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national‐action‐plan‐for‐the‐health‐of‐children‐and‐young‐people‐2020‐2030 (viewed Mar 2023).

- 41. Australian Early Development Census. 2022 AEDC data guidelines. Melbourne: Commonwealth of Australia, 2022. Government https://www.aedc.gov.au/resources/detail/aedc‐data‐guidelines (viewed Mar 2023).

- 42. Goodhue R, Dakin P, Noble K. What's in the Nest? Exploring Australia's Wellbeing Framework for Children and Young People. 2021. Canberra: ARACY, 2021. https://www.aracy.org.au/documents/item/700 (viewed Mar 2023).

- 43. Tasmanian Government. It Takes a Tasmanian Village — Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy. Hobart: Tasmanian Government, 2021. https://hdp‐au‐prod‐app‐tas‐shapewellbeing‐files.s3.ap‐southeast‐2.amazonaws.com/8016/6909/3679/220326_Child_and_Youth_Wellbeing_Strategy_AR_2022_wcag_221122.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 44. Victorian Government. Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS) [website]. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria, 2022. https://www.vic.gov.au/victorian‐child‐and‐adolescent‐monitoring‐system (viewed Feb 2023).

- 45. Telethon Kids Institute. Western Australian Child Development Atlas: CDA Indicators. Perth: Telethon Kids Institute, 2020. https://childatlas.telethonkids.org.au/cda‐indicators/ (viewed Sept 2023).

- 46. Commissioner for Children and Young People, Western Australia. Indicators of Wellbeing [website]. Perth: Government of Western Australia, 2023. https://www.ccyp.wa.gov.au/our‐work/indicators‐of‐wellbeing/ (viewed Feb 2023).

- 47. Australian Capital Territory Government. Children and Young People Lens of ACT Wellbeing Framework [website]. Canberra: ACT Government, 2022. https://www.communityservices.act.gov.au/ocyfs/children/Children‐and‐Young‐People‐Lens‐of‐ACT‐Wellbeing‐Framework (viewed Sept 2023).

- 48. De Vincentiis B, Guthridge S, Su JY, et al. Story of our children and young people, Northern Territory, 2021. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research, 2021. https://cmc.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/1061372/story‐of‐our‐children‐and‐young‐people‐2021.pdf (viewed Mar 2023).

- 49. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy, 2019. Wellington: New Zealand Government, 2019. https://www.childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/resources/child‐and‐youth‐wellbeing‐strategy#foreword‐minister‐for‐child‐poverty‐reduction (viewed Mar 2023).

- 50. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development. OECD child well‐being dashboard. OECD, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/child‐well‐being/data/dashboard/ (viewed Sept 2023).

- 51. UNICEF. Child health and well‐being dashboard. UNICEF, 2022. https://data.unicef.org/resources/child‐health‐and‐well‐being‐dashboard/ (viewed Sept 2023).

- 52. Neuman MJ, Devercelli AE. What matters most for early childhood development: a framework paper. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2013. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/20174 (viewed Mar 2023).

- 53. Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016; 387: 2423‐2478.

- 54. Colyer S. Leadership needed in adolescent health policy. MJA InSight+ 2017, 8 May. https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2017/17/leadership‐needed‐in‐adolescent‐health‐policy/

- 55. Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol 2000; 55: 469‐480.

- 56. Solmi M, Radua J, Olivola M, et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large‐scale meta‐analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol Psychiatry 2022; 27: 281‐295.

- 57. Cleary J, Nolan C, Guhn M, et al. A study protocol for community implementation of a new mental health monitoring system spanning early childhood to young adulthood. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 2022; 14: 1‐20.

- 58. Mason J, Danby S. Children as experts in their lives: child inclusive research. Child Indicators Research 2011; 4: 185‐189.

- 59. Ben‐Arieh A. Where are the children? Children's role in measuring and monitoring their well‐being. Social Indicators Research 2005; 74: 573‐596.

- 60. UNICEF. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [website]. https://www.unicef.org.au/united‐nations‐convention‐on‐the‐rights‐of‐the‐child (viewed Mar 2023).

- 61. Simmons C, Graham A, Thomas NP. Imagining an ideal school for wellbeing: locating student voice. J Educ Chang 2015; 16: 129‐144.

- 62. Victorian Department of Education and Training. Amplify: Empowering Students through Voice, Agency and Leadership. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria, 2019. https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/teachingresources/practice/Amplify.pdf (viewed Sept 2023).

- 63. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth The Nest action agenda: technical document. Canberra: ARACY, 2014. https://www.aracy.org.au/publications‐resources/area?command=record&id=230&cid=22 (viewed Mar 2023).

- 64. VanderWeele TJ, Chen Y, Long K, et al. Positive epidemiology? Epidemiology 2020; 31: 189‐193.

- 65. Australian Data Archive. Australian Child and Adolescent Surveys of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Canberra: ADA, 2014. https://ada.edu.au/australian‐child‐and‐adolescent‐surveys‐of‐mental‐health‐and‐wellbeing/ (viewed May 2023).

- 66. Clark H, Coll‐Seck AM, Banerjee A, et al. A future for the world's children? A WHO–UNICEF–Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020; 395: 605‐658.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley – Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

This article is part of the MJA supplement on the Future Healthy Countdown 2030, which was funded by the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth) — a pioneer in health promotion that was established by the Parliament of Victoria as part of the Tobacco Act 1987, and an organisation that is primarily focused on promoting good health and preventing chronic disease for all. VicHealth has played a convening role in scoping and commissioning the articles contained in the supplement.

VicHealth has assisted with convening the authors who have contributed to the supplement and provided practical supports for organising meetings, liaising with the MJA, and providing administrative assistance. VicHealth has also contributed to discussions on scope and content.

We thank VicHealth staff Zuleika Arashiro, Susan Maury and Louisa Taafua for their assistance in putting together this supplement.

VicHealth funds the supplement and provides support for author collaboration.