Clinical record

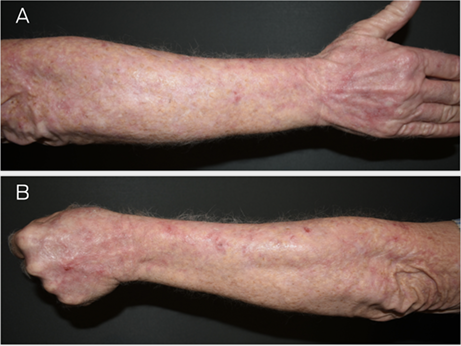

A 62‐year‐old man with a more than 30‐year history of actinic keratoses and keratinocyte carcinomas presented for ongoing management. Over the next ten years, at dermatologist reviews every six months, the patient received treatment for a total of six squamous cell carcinomas, ten basal cell carcinomas, four intra‐epidermal carcinomas, and over 180 actinic keratoses (Box 1). Adjuvant treatments included topical 5% 5‐fluorouracil cream, keratolytic creams, and acitretin (25 mg/day).

At age 72 years, the patient was referred to a radiation oncologist for consideration of field radiotherapy for upper limb actinic keratoses and intra‐epidermal carcinomas. Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) was administered (45 Gy in 25 fractions) sequentially to bilateral extensor forearms, dorsal hands, posterior neck, and scalp. Radiation‐induced dermatitis responded to topical betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment.

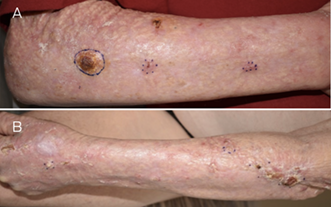

In the ten years before VMAT, the patient had one basosquamous carcinoma and one intra‐epidermal carcinoma on his upper limbs — both cured by simple, uncomplicated excision with his dermatologist. Within 3.5 years after VMAT, he developed ten invasive squamous cell carcinomas in the irradiated skin of his upper limbs. These required excision by a plastic surgeon, as radiation‐induced fibrosis rendered wound closure difficult and healing poor (Box 2). The total lesion counts before and after VMAT are detailed in Box 3.

This complication is rare and idiosyncratic. Given his history before VMAT, the patient might have been at lower risk for significant morbidity from his solar damage‐related skin malignancy and its management, compared with the morbidity he experienced after VMAT.

Discussion

Field cancerisation is a concept increasingly used in relation to skin cancer. Some proposed definitions (Box 4) do not require presence or history of squamous cell carcinoma in the field and fail to distinguish chronic solar damage from true field cancerisation.1,2,3 These definitions capture patients at low risk for keratinocyte carcinoma, which would be easily managed with usual modalities. Labelling what most would term “solar damaged skin” as field cancerisation might lead to interventions with limited benefit and significant morbidity.

Radiotherapy has a long‐standing and well recognised role in skin cancer management for definitive individual lesions. As yet, the utility and safety of radiotherapy in managing mere solar damage and actinic keratosis are unknown.

VMAT is a modern radiotherapy technique that is increasingly being promoted for skin field cancerisation.4 Listed indications include extensive cancerisation across large fields or high tumour load, high risk of recurring lesions, patients that are not surgical candidates, and failure of other therapies. Long term outcome data of VMAT for skin field cancerisation are not available.

In contrast to other field‐directed treatments, ionising radiation can produce irreversible complications that worsen over time. Development of post‐irradiation skin toxicity depends on dose, fractionation, technique, and type of radiotherapy, as well as concurrent treatment and comorbid conditions affecting the skin. Mechanisms underlying delayed radiation changes are complex, involve all layers of the skin, and have prominent features of vascular damage and fibrosis.5

Keratinocyte carcinomas developing in previously irradiated fields could represent recurrence or new primary lesions. Dosages used in field radiotherapy might undertreat invasive keratinocyte carcinomas originally present.

Re‐irradiation can induce severe iatrogenic complications due to the cumulative dose in the context of already decreased tissue tolerance from previous radiotherapy. Therefore, field VMAT treatment precludes safe future radiotherapy use. Surgery in irradiated skin is complicated by distorted anatomy, challenging wound closure due to reduced elasticity and fibrosis, and increased risk of wound ulceration and necrosis.5

This case demonstrates an uncommon but substantial irreversible complication of field radiotherapy that affected further management and produced significant patient morbidity. A practical definition of skin field cancerisation and recommendations for the use of field VMAT to skin with careful risk–benefit analysis are needed with multidisciplinary input. These should be based on carefully conducted, controlled trials with at least ten years of follow‐up. The management of patients with severely sun‐damaged skin is an important clinical challenge, particularly in Australia. Further research regarding available treatment modalities for patients with high burdens of keratinocyte cancer and the development of comprehensive management guidelines would be valuable.

Lessons from practice

- Field cancerisation is an evolving concept in skin cancer medicine that currently lacks a workable definition and management guidelines.

- Radiotherapy has a role in skin cancer management, but careful risk–benefit analysis is essential. Guidelines are needed with multidisciplinary input from general practitioners, physicians, dermatologists, surgeons, and radiation oncologists for the use of field volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) in skin.

- Post‐irradiation skin toxicity limits management options for subsequent skin cancer in the previously irradiated field and increases the risk of surgical complications.

- Promotion of VMAT to the general public should be avoided until the role for this modality has been determined by high quality research.

Box 1 – Actinic damage bilateral forearms before radiatiotherapy (A, right forearm; B, left forearm)

Box 2 – Squamous cell carcinoma arising in irradiated field: (A) right forearm 11 months after radiotherapy, (B) left forearm 15 months after radiotherapy

Box 3 – Cutaneous malignancy before and after volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), administered in 2017*

|

|

Years |

VMAT area |

Non‐VMAT area |

All areas total |

|||||||||||

|

BCC |

IEC/SCC† |

Total |

BCC |

IEC/SCC |

Total |

BCC |

IEC/SCC |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Before VMAT |

2008–2017 |

4 |

5‡ |

9 |

6 |

5 |

11 |

10 |

10 |

||||||

|

After VMAT |

2017–2022 |

0 |

17§ |

17 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

18 |

||||||

|

2022¶ |

2 |

8 |

10 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

|||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

BCC = basal cell carcinoma; IEC = intra‐epidermal carcinoma; SCC = squamous cell carcinoma. * Within 3.5 years after VMAT (May 2021), the patient developed ten invasive SCCs in irradiated skin of his upper limbs. † Basosquamous carcinoma was accounted for in IEC/SCC count. ‡ Two upper limbs. § Ten upper limbs. ¶ Clinically diagnosed. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Current definitions of field cancerisation

|

Reference |

Proposed definitions of field cancerisation |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Willenbrink et al1 |

“Multifocal clinical atypia characterized by [actinic keratoses] or squamous cell carcinomas in situ with or without invasive disease, occurring in a field exposed to chronic [ultraviolet radiation].” |

||||||||||||||

|

Christensen et al2 |

“A practical working definition of field cancerization requires three features: a defined region of skin, multiple [actinic keratoses] within that region, and at least one prior [squamous cell carcinoma].” |

||||||||||||||

|

Figueras Nart et al3 |

“Field cancerization is clinically defined as the anatomical area with or adjacent to [actinic keratoses] and visibly sun damaged skin identified by at least two of the following signs: telangiectasia, atrophy, pigmentation disorders and sand paper [sic]. It is unclear if a visible [actinic keratosis] lesion is needed for field cancerization.” |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- 1. Willenbrink TJ, Ruiz ES, Cornejo CM, et al. Field cancerization: definition, epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 709‐717.

- 2. Christensen SR. Recent advances in field cancerization and management of multiple cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas. F1000Res 2018; 7: F1000 Faculty Rev‐690.

- 3. Figueras Nart I, Cerio R, Dirschka T, et al. Defining the actinic keratosis field: a literature review and discussion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 544‐563.

- 4. Fogarty GB, Christie D, Spelman LJ, et al. Can modern radiotherapy be used for extensive skin field cancerisation: an update on current treatment options. Biomed J Sci Tech Res 2018; 4: BJSTR.2018.04.000998.

- 5. Bray FN, Simmons BJ, Wolfson AH, Kouri K. Acute and chronic cutaneous reactions to ionizing radiation therapy. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2016; 6: 185‐206.

Open access:

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Queensland, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Queensland agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Patient consent

The patient gave written consent for publication.

No relevant disclosures.