Physician burnout has negative effects on patient safety and quality of care, and may contribute to medical errors.1 There is a growing literature on wellbeing in specific medical and surgical specialties overseas, but information about specialty‐specific wellbeing in Australia is limited.2,3

We therefore undertook a survey to assess distress and examine demographic factors associated with distress in orthopaedic surgery trainees. We assessed distress levels with the Physician Well‐Being Index (PWBI; MedEd Web Solutions; https://www.mywellbeingindex.org/versions/physician‐well‐being‐index). The PWBI, a 7‐item screening tool, includes the domains burnout, depression, stress, fatigue, and mental and physical quality of life; it has been validated in postgraduate medical and surgical trainees.4 A PWBI score greater than 4 is typically interpreted as indicating distress; the likelihood of low mental quality of life, high fatigue, and suicidal ideation were each much higher in the American validation study for residents with scores above 4 than for those with scores of 4 or less.4

The Australian Orthopaedic Association emailed all 230 Australian orthopaedic registrar trainees two invitations to participate in our online survey during 25 October 2021 – 7 December 2021. Apart from the PWBI, the survey included questions about gender; whether the respondent had dependents under 18 years of age, an ethnic minority background, or a long term mentor with whom they communicated regularly; their year of training; and fellowship examination status (passed, attempted but not yet passed, not yet attempted). Survey responses were submitted anonymously, and collected and managed using REDCap software. The Royal Children's Hospital Research Ethics and Governance approved our study (QA/73257/RCHM‐2021).

The survey response rate was 38% (88 responses). Burnout during the 30 days preceding completion of the survey was reported by 55 respondents (63%). Thirty‐nine respondents (11 of 19 women, 58%; 28 of 69 men, 41%) met the PWBI criterion for distress (44%) (Box 1). Nine of 17 respondents with minority ethnic backgrounds (53%) and 30 of 71 from non‐minority backgrounds (42%) met the PWBI criterion for distress (Box 2).

Twenty‐two trainees wished they had chosen a career outside medicine (25%); fourteen wished that they had selected a medical specialty other than orthopaedic surgery (16%) (Box 2). Five of 29 trainees who had already passed the fellowship exam (17%) wished they had pursued non‐medical careers, and six wished they had chosen a medical specialty other than orthopaedic surgery (21%).

As only 38% of trainees responded to the survey, our sample may not be representative. The effect of responder bias on our survey, undertaken during the COVID‐19 pandemic, is unclear, particularly given differences between states in the experiences of orthopaedic trainees during this period. To alleviate concerns about identifiability, we did not ask respondents about the state where they were training. The proportion of female respondents (22%) was larger than the proportion of orthopaedic registrar trainees who are women (39 of 230, 17%; personal communication: Belinda Balhatchet, Australian Orthopaedic Association, October 2022).

Our findings suggest that distress among orthopaedic registrar trainees is common, particularly among women, and many trainees expressed career regret. Further research is required to improve knowledge about factors that contribute to distress in medical and surgical specialties in Australia and to assist with averting and mitigating physician burnout.

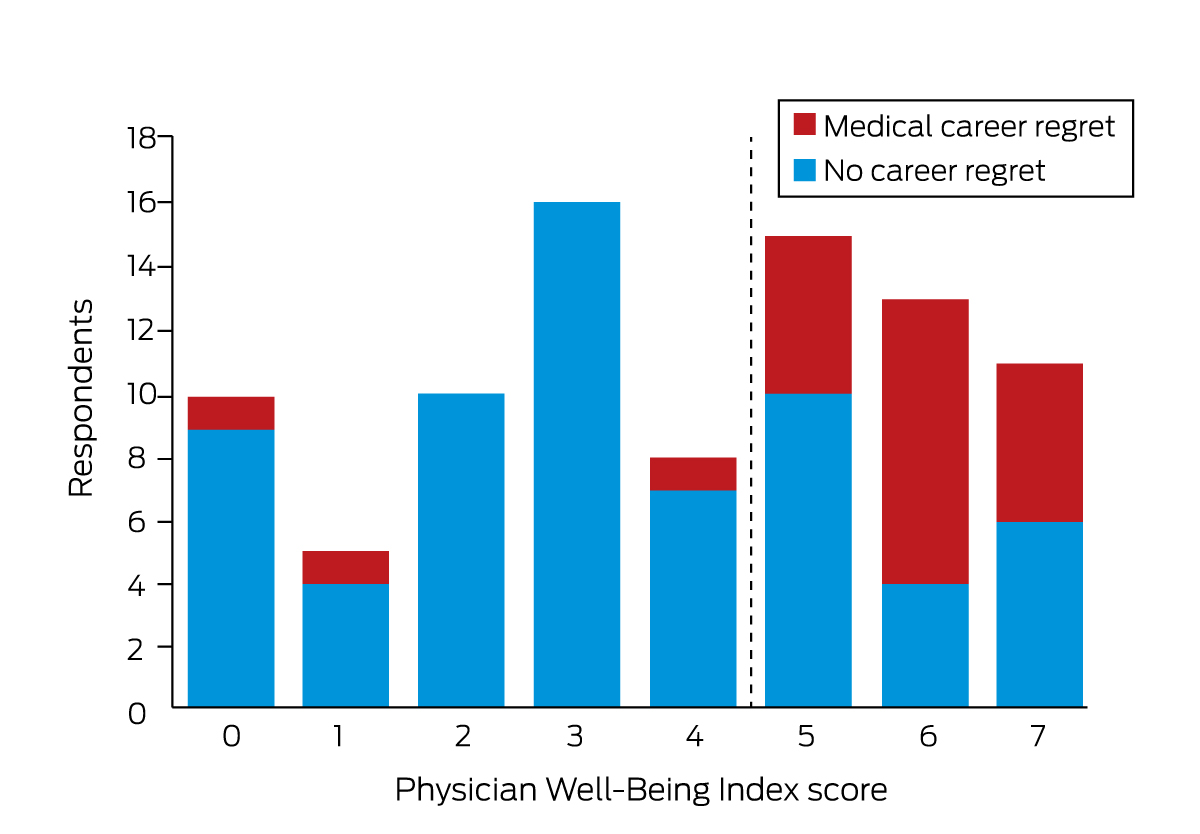

Box 1 – Physician Well‐Being Index scores* and medical career regret† for 88 orthopaedic registrar trainee survey respondents

* Score greater than 4 indicates distress. † Survey respondent regretted having chosen a medical career.

Box 2 – Characteristics of 88 orthopaedic registrar trainee survey respondents, and of 39 respondents classified by their Physician Well‐Being Index (PWBI) scores as experiencing distress

|

Characteristic |

All respondents |

Respondents experiencing distress |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Respondents |

88 |

39 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Women |

19 (22%) |

11 |

|||||||||||||

|

Men |

69 (78%) |

28 |

|||||||||||||

|

Ethnic background |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Minority |

17 (19%) |

9 |

|||||||||||||

|

Non‐minority |

71 (81%) |

30 |

|||||||||||||

|

Dependents (minors) |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Yes |

51 (58%) |

23 |

|||||||||||||

|

No |

37 (42%) |

16 |

|||||||||||||

|

Mentorship |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Has a mentor |

38 (43%) |

14 |

|||||||||||||

|

No mentor |

50 (57%) |

25 |

|||||||||||||

|

Training year |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

1 |

14 (16%) |

6 |

|||||||||||||

|

2 |

15 (17%) |

6 |

|||||||||||||

|

3 |

17 (19%) |

5 |

|||||||||||||

|

4 |

18 (20%) |

11 |

|||||||||||||

|

5 |

21 (24%) |

10 |

|||||||||||||

|

Not disclosed |

3 (3%) |

1 |

|||||||||||||

|

Fellowship exam |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Not yet attempted |

56 (64%) |

23 |

|||||||||||||

|

Attempted not yet passed |

3 (3%) |

3 |

|||||||||||||

|

Passed |

29 (33%) |

13 |

|||||||||||||

|

Career regret |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Wished they had chosen a non‐medical career |

22 (25%) |

19 |

|||||||||||||

|

Wished they had chosen another medical specialty |

14 (16%) |

11 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Received 28 April 2022, accepted 29 October 2022

- 1. Lu DW, Dresden S, McCloskey C, et al. Impact of burnout on self‐reported patient care among emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med 2015; 16: 996‐1001.

- 2. Arora M, Diwan AD, Harris IA. Prevalence and factors of burnout among Australian orthopaedic trainees: a cross‐sectional study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2014; 22: 374‐377.

- 3. Raftopulos M, Wong EH, Stewart TE, et al. Occupational burnout among otolaryngology‐head and neck surgery trainees in Australia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019; 160: 472‐479.

- 4. Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Sloan J, Shanafelt TD. Ability of the physician well‐being index to identify residents in distress. J Grad Med Educ 2014; 6: 78‐84.

No relevant disclosures.