About one in 13 Australians over the age of 40 years is estimated to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).1 In 2018, COPD was the leading cause of potentially preventable hospitalisations,2 the third leading specific cause of total disease burden,3 and the fifth leading cause of death in Australia.3 This represents a significant burden in the lives of individuals living with COPD and within the Australian health care system. Importantly, the impact of COPD is even greater among Indigenous Australians compared with non‐Indigenous Australians.4

Changes in diagnosis, assessment and management as a result of the guidelines

The significant rate of potentially preventable hospitalisations for COPD reported by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare in the Admitted patient care 2017–18: Australian hospital statistics suggests that people living with COPD have inadequate access to guidelines‐based care within the community setting.5 According to the fourth Atlas of Healthcare Variation developed by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, hospitalisations for COPD were 18 times higher in the local area with the highest rate compared with the area with the lowest rate,6 suggesting inequity in resources and availability/quality of care across different geographic areas.

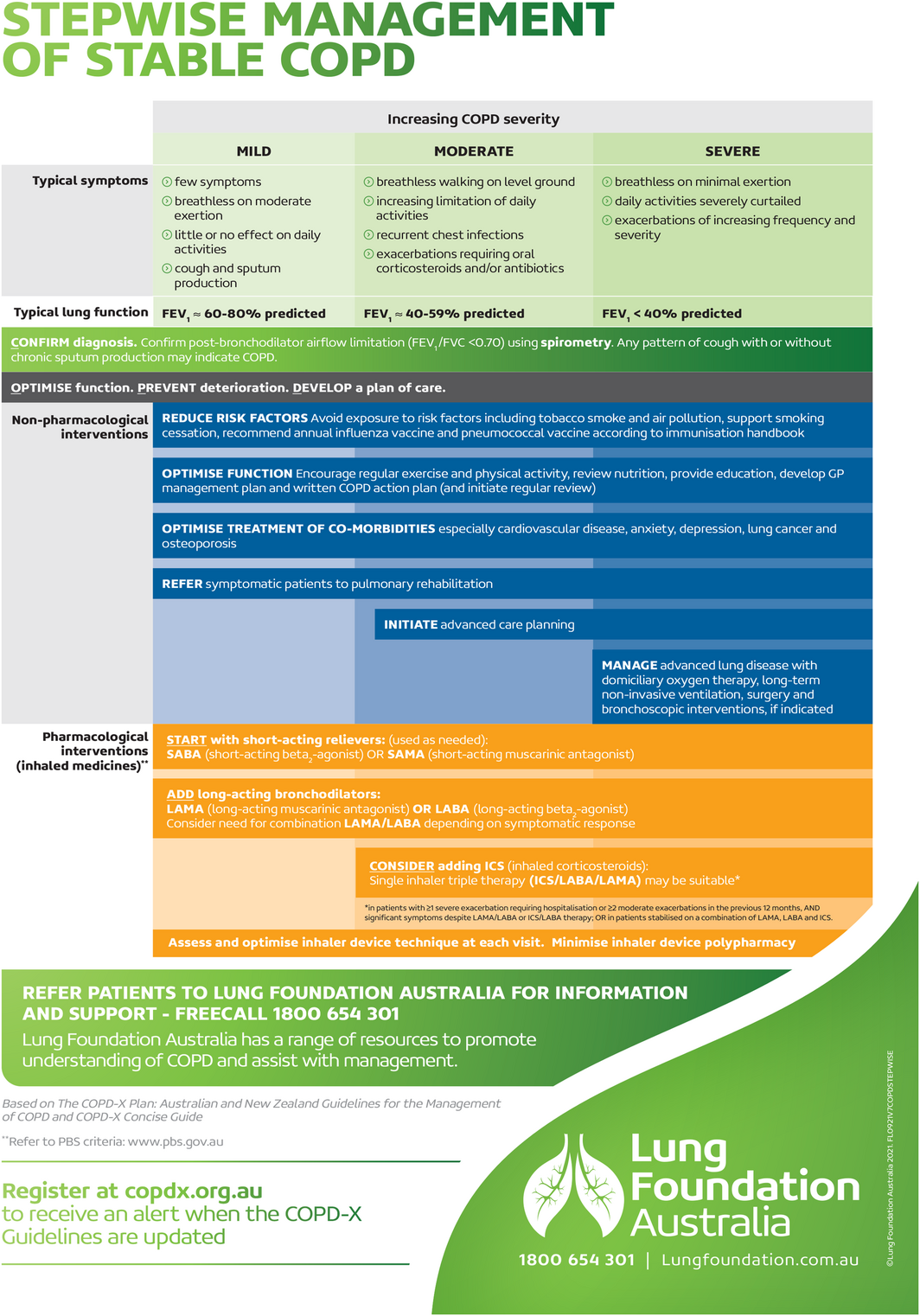

COPD‐X was first published as a supplement to The Medical Journal of Australia (MJA) in 2003, and a major update was then published in the MJA in 2017.7 The guidelines are written by a multidisciplinary group of Australian clinicians and strive to provide evidence‐based recommendations relevant for Australian health care workers. The guidelines are updated quarterly, published by the Lung Foundation Australia in conjunction with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (http://copdx.org.au). They emphasise the importance of non‐pharmacological therapy for the management of COPD and promote the concept of “stepwise management”, beginning with one pharmacological intervention and evaluating response before adding another agent (Box 1 and Box 2). The guidelines aspire to standardise COPD care, optimise health outcomes, and enhance the quality of life of people with COPD.

Methods

The guidelines manager at Lung Foundation Australia performs a quarterly systematic literature search (developed by a medical librarian) for COPD within PubMed for new literature (Supporting Information, appendix 1). Following screening, included articles are critically appraised by a COPD‐X Guidelines Committee member with relevant expertise. If appropriate, the article is cited, and wording changed within the relevant section as recommended by the reviewer (Supporting Information, table 1). Changes are finalised through a consensus approach. Biannually, the quarterly update is reviewed for endorsement by the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand.

C: Confirm diagnosis

People living with COPD experience persistent respiratory symptoms (breathlessness, cough and sputum, exacerbations) associated with chronic airflow obstruction,8 which requires confirmation by spirometry (post‐bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] to forced vital capacity [FVC] ratio < 0.7). Access to spirometry can be challenging and has worsened during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, given that spirometry may be an aerosol‐generating procedure. However, at the time of writing, access in some locations has improved, with respiratory scientists using personal protective equipment.

Cigarette smoking is the major cause of COPD, although many non‐tobacco risk factors contribute globally,9 including air pollution, occupational exposures, asthma, and submaximal lung growth.10 Given the broad differential diagnosis for breathlessness,11 thorough history, examination and investigations should be undertaken. In a study of 1050 smokers in 41 general practices, more than one‐third of patients with a diagnosis of COPD did not meet spirometric criteria (ie, misdiagnosed), whereas one in six had undiagnosed COPD (ie, missed diagnosis).12 Case‐finding and better access to spirometry improves the diagnosis of COPD. People with COPD should undergo a multidimensional assessment for treatable traits, including airflow obstruction (spirometry), inflammation (blood eosinophil levels), and behaviour and risk factors (smoking, treatment adherence, self‐management skills, physical activity, and comorbid conditions).13,14

O: Optimise function

Non‐pharmacological therapy

The evidence for pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD is summarised in Box 3.

Physical activity. Individuals who meet physical activity guideline recommendations demonstrate reductions in all‐cause and respiratory mortality risk,22 providing further support for encouraging walking and structured exercise in people with COPD with the aim of reducing mortality risk (Level of Evidence [LoE] III‐2, weak recommendation).

Frailty. Measuring frailty may identify vulnerable people living with COPD and allow earlier interventions such as pulmonary rehabilitation to improve breathlessness, exercise performance, physical activity level and health status23 (LoE III‐2, weak recommendation).

Pharmacological therapy

Pharmacological treatments aim to reduce symptoms, prevent exacerbations, and improve health status.24,25 The inhalation route is primarily used for direct delivery of medicines to the lungs. Adherence to recommended treatment and optimal inhaler technique are critical.

Short‐ and long‐acting inhaled bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) should be prescribed using a stepwise approach.24,25 Short‐acting bronchodilators are used when required for short term symptom relief. Long‐acting bronchodilators (long‐acting muscarinic antagonists [LAMAs] and long‐acting β‐agonists [LABAs]) are given on a regular basis (once or twice daily) to prevent or reduce symptoms.26 LAMAs are associated with a greater reduction in exacerbations than LABAs.27 Dual bronchodilator therapy (LABA/LAMA) is superior to either LABA or LAMA monotherapy, with a 20% reduction in acute exacerbations and 11% reduction in hospitalisations on average28 (LoE I, strong recommendation). In people with COPD with dyspnoea and exercise intolerance, triple therapy (ICS/LAMA/LABA) is not superior to maintenance long‐acting bronchodilator therapy, except in people with a history of one or more exacerbations in the past year, in whom the benefits of reduction in exacerbations outweigh the increased risk of pneumonia.29 Triple therapy should be limited to people with exacerbations and more severe COPD symptoms that cannot be adequately managed by dual therapy (LABA/LAMA) (LoE I, strong recommendation).

Long term oral glucocorticoid therapy is associated with severe side effects without evidence of benefit in stable COPD.

Comorbid conditions

A range of comorbid conditions in COPD (Box 4) are associated with higher readmission rates,40 cardiac events and mortality. A large general practice dataset in the United Kingdom showed that COPD was associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, stroke and diabetes mellitus.41 Box 4 summarises the most common comorbid conditions in COPD.

Lung volume reduction

All people with COPD being considered for lung volume reduction surgery and bronchoscopic lung volume reduction should be referred for pulmonary rehabilitation and discussed by an expert panel that includes a radiologist, respiratory physician, interventional pulmonologist and thoracic surgeon.42 A meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials across all modalities of lung volume reduction (surgical and endobronchial) demonstrated improvement in lung function, exercise capacity and quality of life (LoE I, weak recommendation).43 However, study rigour was limited by a lack of blinding, and the odds ratio for a severe adverse event, which included mortality, was 6.21 (95% CI, 4.02–9.58) following intervention.

Lung volume reduction surgery should only be considered in high volume specialised centres.42 Bronchoscopic lung volume reduction may be appropriate in highly selected people with severe emphysema and hyperinflation. A meta‐analysis of six trials of endobronchial valves (620 participants) and three trials of coils (458 participants) reported improvements in lung function, 6‐minute walk distance and symptom scores with both modalities.43 The odds ratio for an adverse event for trials of endobronchial valves was 9.58 (95% CI, 5.56–16.50), with the most frequent adverse events being pneumothorax (range, 1.4–25%) and exacerbations (range, 4–20%).

P: Prevent deterioration

Smoking cessation

Tobacco smoking is the key risk factor for development of COPD, and smoking cessation is the only intervention shown to slow decline in lung function44 (LoE I, strong recommendation). Coexisting anxiety and depression are important barriers to successful cessation. Smoking cessation advice from health professionals has been shown to increase quit rates45 (LoE I, strong recommendation). Hospital admission represents an opportunity to initiate smoking cessation, but support needs to continue after discharge.

Supporting smoking cessation involves behavioural support and treatment of nicotine dependence. Counselling may be structured using the five As strategy: ask, assess, advise, assist and arrange follow‐up.46 Brief advice to quit and referral to the Quitline (13 78 48) is an alternative option. The most effective medicines approved for treating nicotine dependence are either combination nicotine replacement therapy or varenicline47 (LoE I, strong recommendation). Longer courses of treatment may reduce relapse46 (LoE I, strong recommendation). Nicotine vaping may assist selected patients46 but is not approved as a medicine and long term safety is unknown.

Immunisation

Educational interventions for primary health professionals may improve influenza vaccination rates among patients with COPD and patient satisfaction with care (Box 5).50

Oxygen therapy

Oxygen therapy may be of benefit in people with significant hypoxaemia but is not recommended for individuals who continue to smoke (due to risk of burns and injury). Continuous or long term oxygen therapy (> 15–18 h/day) can improve survival in people with severe hypoxaemia (arterial partial pressure of oxygen [PaO2] ≤ 55 mmHg or PaO2 ≤ 59 mmHg with pulmonary hypertension) (LoE I, strong recommendation).51,52 No benefits in quality of life, lung function, exercise capacity or mortality were demonstrated with long term oxygen therapy in a large study of people with moderate resting hypoxaemia (oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry [SpO2], 89–93%) or modest exercise‐induced desaturation53 (LoE II, strong recommendation). Nocturnal oxygen in individuals who desaturated for more than one‐third of the night did not improve survival or progression to long term oxygen therapy54 (LoE II, strong recommendation). The benefits of ambulatory oxygen are unclear, and the associated burden may outweigh the limited benefits observed in laboratory‐based studies.55,56

Prophylactic antibiotics

Macrolide antibiotics given daily or three times a week may reduce exacerbations in people with moderate to severe COPD and frequent exacerbations57 (LoE I, weak recommendation). However, this benefit comes with increased risks of gastrointestinal side effects, potential cardiac toxicity, ototoxicity, and the development of antibiotic resistance. COPD‐X recommends maximal inhaled and other preventive therapies, including smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation, vaccination, and review of inhaled therapies, before consideration of prophylactic antibiotics, with careful weighing of risk and benefit. A network meta‐analysis comparing long term treatment with tetracyclines or quinolones for prevention of exacerbations found they were no better than placebo58 (LoE I, strong recommendation).

Biologic therapies

There is evidence to suggest that eosinophil may be an important biomarker for both increased exacerbations and corticosteroid responsiveness in COPD. Studies aimed at depleting eosinophils with anti‐interleukin‐5 therapies (mepolizumab and benralizumab) have had variable results, but these treatments likely reduce moderate and severe exacerbations in subgroups of people with higher blood eosinophil levels.59 Further studies with cost‐effectiveness analyses are needed to assist in determining the role of these monoclonal antibody therapies.

Palliative care

Palliative care from a multidisciplinary team should be considered early, to address symptom control and psychosocial issues. An Australian study found that in the last two years of life, only 18% of people with severe COPD accessed specialist palliative care, with only 6% prescribed opioids, despite severe breathlessness.60 Extended‐release morphine can improve health status in people with COPD who have uncontrolled breathlessness.61 Advanced care planning should occur early.

Home bilevel ventilation

Long term nocturnal bilevel non‐invasive ventilation (NIV) delivered by a face mask is a technique to support ventilation. Long term NIV should be considered in people with stable COPD and hypercapnia (LoE I, weak recommendation). These people should be referred to a centre with expertise in home NIV. A 2021 meta‐analysis found that when NIV is used in people with stable severe COPD and daytime hypercapnia, there is a short term improvement in health‐related quality of life and a reduction in mortality.62 However, when NIV is commenced after an exacerbation, there is an improvement in rate of hospital admissions but no improvement in health‐related quality of life.

D: Develop a care plan

The data from systematic reviews suggest that COPD self‐management programs improve health‐related quality of life.63,64,65,66,67 However, the effect of these interventions on exacerbations remains unclear. Some studies report positive outcomes, although increased rates of exacerbations are reported in another large self‐management intervention randomised controlled trial.68 Due to the heterogeneity of the study designs, setting and outcomes, and conflicting results, essential elements of COPD self‐management programs cannot be recommended.

Even though, overall, the essential elements remain unknown, some components of self‐management are consistently associated with improved outcomes. Optimising inhaler technique is one such element. However, despite recognition of its importance, inhaler technique in people with COPD is consistently poor,69 and poor technique is associated with adverse health outcomes. Furthermore, the number of inhaler devices prescribed is also important. People with COPD who use multiple but similar style devices have been found to experience fewer exacerbations compared with a mixed device cohort.70

Suboptimal adherence is also associated with adverse health outcomes.71 To improve adherence and inhaler technique, it is recommended to minimise the number of different devices by prescribing medications via the same or similar inhaler platform where appropriate (LoE II, weak recommendation). COPD‐X also recommends patient education that involves demonstration of correct inhaler technique and observation, as well as interventions to improve adherence, and that these be performed regularly (LoE I, strong recommendation).

A key element of self‐management is COPD exacerbation action plans. Exacerbation action plans reduce emergency department visits and hospital admissions72 (LoE I, strong recommendation). A comprehensive, intensive health coaching intervention led to reduced COPD‐related admissions in the short term (up to 6 months, but not at 12 months).73 In contrast, several more recent randomised controlled trials of telehealth self‐management have failed to demonstrate benefits in exacerbation reduction or health care utilisation.74,75,76,77

X: Manage exacerbations

A COPD exacerbation is a worsening of dyspnoea, cough and/or sputum beyond normal day‐to‐day variations which is acute in onset and may warrant additional treatment or hospital admission. A history of COPD exacerbations is the best predictor of subsequent exacerbations.78,79 A COPD exacerbation should be considered a sentinel event with a 12‐month mortality rate of over 25%.80 Exacerbations can be caused by bacterial or viral infections, heart failure, air pollution and social stressors. Pulmonary embolism should be excluded when there are no signs of infection.81 Effective communication between hospital teams and primary care is essential, particularly after a hospital admission.

Pharmacological management of exacerbations

Salbutamol four to eight puffs (400–800 μg) should be administered via a metered dose inhaler with spacer every 3–4 hours. Nebulisers are not superior,82 but if used, they should be driven by air and not oxygen.83 Oral prednisolone (30–50 mg) should be given for 5 days84 (LoE I, strong recommendation). Intravenous corticosteroids and prolonged courses of corticosteroids are not superior,85 with prolonged courses associated with increased mortality rates.86 People with COPD with signs of a chest infection (increased sputum volume/purulence or fever) should be treated with an oral antibiotic (LoE I, strong recommendation). First line antibiotics are amoxicillin or doxycycline for 5 days.87 A chest x‐ray should be performed if hospital admission is required or if pneumonia is suspected.

Oxygen therapy and non‐invasive ventilation

Oxygen therapy should be administered only if hypoxaemia is present, with the target SpO2 of 88–92%.88 This can usually be achieved with oxygen via nasal prongs at 0.5–2 L/min. Over‐oxygenation leads to increased mortality (LoE II, strong recommendation).89 People presenting to hospital with a severe exacerbation of COPD should be assessed with an arterial blood gas test. If hypercapnic respiratory failure is present (pH < 7.35 and PaCO2 > 45 mmHg), NIV is indicated. NIV leads to reductions in mortality, length of stay and endotracheal intubation rates90 (LoE I, strong recommendation).

Further resources

For full details of the evidence, references, and regular updates, please refer to the COPD‐X guidelines at http://copdx.org.au. COPD resources are available from the Lung Foundation Australia (www.lungfoundation.com.au) (Box 6).

Box 1 – Summary of key evidence and recommendations of the COPD‐X guidelines

|

Recommendation |

NHMRC level of evidence* |

GRADE strength of recommendation |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

C: Case finding and confirm diagnosis |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Smoking is the most important risk factor in COPD development |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Smoking cessation reduces mortality |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

COPD is confirmed by the presence of persistent airflow limitation (post‐bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7) |

III‐2 |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

O: Optimise function |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Optimise pharmacotherapy using a stepwise approach |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Adherence and inhaler technique need to be checked on a regular basis |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Pulmonary rehabilitation improves quality of life and exercise capacity and reduces COPD exacerbations |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Comorbid conditions are common in people with COPD |

III‐2 |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Palliative care (ideally from a multidisciplinary team that includes the primary care team) should be considered early, and should include symptom control and management of psychosocial issues† |

II |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Lung volume reduction (surgical and endobronchial) improves lung function, exercise capacity and quality of life† |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Long term macrolide antibiotics may reduce exacerbations in people with moderate to severe COPD and frequent exacerbations† |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Long term non‐invasive ventilation should be considered in people with stable COPD and hypercapnia to reduce mortality† |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

P: Prevent deterioration |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Smoking cessation is the most important intervention to prevent worsening of COPD |

II |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Preventing exacerbations has a key role in preventing deterioration |

III‐2 |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination reduce COPD exacerbations |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Long term oxygen therapy has survival benefits for people with COPD and hypoxaemia |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

D: Develop a plan of care |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Clinical support teams working with the primary health care team can help enhance quality of life and reduce disability for patients with COPD |

III‐2 |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Patients may benefit from self‐management support |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

COPD exacerbation action plans reduce emergency department visits and hospital admissions† |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

X: Manage exacerbations |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Early diagnosis and treatment of exacerbations may prevent hospital admission and delay COPD progression |

III‐2 |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Multidisciplinary care may assist home management of some patients with an exacerbation |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Inhaled bronchodilators are effective for initial treatment of exacerbations |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Systemic corticosteroids reduce the severity of and shorten recovery from exacerbations |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Exacerbations with clinical features of infection (increased volume and change in colour of sputum and/or fever) benefit from antibiotic therapy |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

When using supplemental oxygen for hypoxia in COPD exacerbations, target SpO2 88–92% improves survival |

II |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Non‐invasive ventilation improves survival for people with COPD and acute hypercapnic respiratory failure |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Consider pulmonary rehabilitation at any time, including during the recovery phase following an exacerbation |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC = forced vital capacity; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NHMRC = National Health and Medical Research Council; SpO2 = oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry. * NHMRC levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines, 2009 (https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/images/NHMRC%20Levels%20and%20Grades%20(2009).pdf; Supporting Information, appendix 1). † Denotes new recommendations not included in Yang et al.7 |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – Stepwise management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) fact sheet

FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC = forced vital capacity. Source: Figure reproduced with permission from Stepwise Management of Stable COPD (March 2022); Lung Foundation Australia (https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/stepwise‐management‐of‐stable‐copd/).

Box 3 – Pulmonary rehabilitation recommendations

|

Recommendation |

NHMRC level of evidence* |

GRADE strength of recommendation |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

People with mild to severe COPD should undergo pulmonary rehabilitation to improve quality of life and exercise capacity and to reduce hospital admissions15 |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

Pulmonary rehabilitation can be offered in hospital gyms, community centres or at home, and can be provided with or without an education program15,16 |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Pulmonary rehabilitation should be offered to people with any long term respiratory disorder characterised by dyspnoea, such as bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension15 |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Pulmonary rehabilitation should be provided after an exacerbation of COPD, commencing within 2–4 weeks of hospital discharge15,17 |

I |

Strong |

|||||||||||||

|

The provision of supplementary oxygen in people with COPD who desaturate during exercise training does not improve the benefit from training15 |

II |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Tai Chi may be a potential treatment option when pulmonary rehabilitation is not available18 |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Elastic resistance training may be an alternative to conventional resistance training using weight machines19,20 |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

Telerehabilitation is effective in improving exercise capacity and reducing hospitalisations20,21 and may enable people with high symptom burden or travel restrictions to access pulmonary rehabilitation |

II |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

More research is needed to determine the optimal model of maintenance exercise programs, but some form of regular exercise should be encouraged following completion of a pulmonary rehabilitation program to sustain the benefits gained15 |

I |

Weak |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; NHMRC = National Health and Medical Research Council. For further information on pulmonary rehabilitation please refer to the Australian guidelines.15 * NHMRC levels of evidence and grades for recommendations for developers of guidelines, 2009 (https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/images/NHMRC%20Levels%20and%20Grades%20(2009).pdf; Supporting Information, appendix 1). |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 – Comorbid conditions associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

|

Comorbid condition |

Associated evidence |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Cardiac events |

A meta‐analysis30 and a Cochrane systematic review31 concluded that cardio‐selective β‐blockers are safe in COPD and should not be withheld, even in people with severe airflow limitation, including during exacerbations32 |

||||||||||||||

|

Osteoporosis |

Osteoporosis is common in COPD (mean prevalence 38%) and is a predictor of higher mortality and worse lung function33 |

||||||||||||||

|

Anxiety and depression |

Anxiety and depression are important comorbid conditions, especially in females,34 and are associated with higher readmission rates35 |

||||||||||||||

|

Obstructive sleep apnoea |

Obstructive sleep apnoea is very common in COPD36 and is associated with higher mortality and more frequent exacerbations37 |

||||||||||||||

|

Bronchiectasis |

Bronchiectasis often coexists with COPD, and a high resolution computed tomography chest scan should be considered when chronic sputum production or frequent respiratory infections are present to identify clinically important bronchiectasis that should be managed38,39 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 – Immunisations to reduce risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations

|

Immunisation |

Recommendation |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Influenza |

Annual influenza immunisation has been shown to reduce the risk of exacerbations and hospitalisations in people with COPD48 and is therefore strongly recommended (LoE I, strong recommendation) |

||||||||||||||

|

Pneumococcal |

Pneumococcal immunisation reduces exacerbations of COPD and is recommended for people with COPD49 (LoE I, strong recommendation)* |

||||||||||||||

|

SARS‐CoV‐2 |

COPD is associated with increased risk of severe COVID‐19 and people with COPD should be encouraged to get vaccinated† (Expert opinion) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COVID‐19 = coronavirus disease 2019; LoE = Level of Evidence; SARS‐CoV‐2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. * For details of the immunisation schedule please refer to the Australian Immunisation Handbook (https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/). † Please refer to https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/hcp/clinical‐care/underlyingconditions.html. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Dedicated resources aligned with the COPD‐X Guidelines

|

|

Resources |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

For health professionals |

Stepwise Management of Stable COPD: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/stepwise‐management‐of‐stable‐copd |

||||||||||||||

|

COPD‐X Concise Guide: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/copd‐x‐concise‐guide/ |

|||||||||||||||

|

For people living with COPD and their support network |

My COPD Checklist: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/my‐copd‐checklist/ |

||||||||||||||

|

COPD Action Plan: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/copd‐action‐plan/ |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. |

|||||||||||||||

Provenance: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Eli Dabscheck1

- Johnson George2

- Kelcie Hermann3

- Christine F McDonald4

- Vanessa M McDonald5

- Renae McNamara6

- Mearon O’Brien3

- Brian Smith7

- Nicholas A Zwar8

- Ian A Yang9,10

- 1 Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Centre for Medicine Use and Safety, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Lung Foundation Australia, Brisbane, QLD

- 4 Austin Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 5 Centre for Healthy Lungs, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW

- 6 Prince of Wales Hospital and Community Health Services, Sydney, NSW

- 7 Bendigo Health, Bendigo, VIC

- 8 Bond University, Gold Coast, QLD

- 9 University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD

- 10 Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, QLD

We thank Pamela Gabrovska for contributing to the bibliography.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Toelle BG, Xuan W, Bird TE, et al. Respiratory symptoms and illness in older Australians: the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study. Med J Aust 2013; 198: 144‐148. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2013/198/3/respiratory‐symptoms‐and‐illness‐older‐australians‐burden‐obstructive‐lung

- 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disparities in potentially preventable hospitalisations across Australia, 2012–13 to 2017–18 [Cat. No. HPF 50]. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary‐health‐care/disparities‐in‐potentially‐preventable‐hospitalisations‐australia/summary (viewed Mar 2021).

- 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [Cat. No. ACM 35]. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic‐respiratory‐conditions/copd/contents/copd (viewed Oct 2021).

- 4. Australian Institute for Health and Welfare and National Indigenous Australians Agency. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: 1.04 respiratory disease. https://www.indigenoushpf.gov.au/measures/1‐04‐respiratory‐disease (viewed Mar 2021).

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Admitted patient care 2017–18: Australian hospital statistics [Cat. No. HSE 225]. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/df0abd15‐5dd8‐4a56‐94fa‐c9ab68690e18/aihw‐hse‐225.pdf (viewed Jan 2022).

- 6. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. The Fourth Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021‐04/The%20Fourth%20Australian%20Atlas%20of%20Healthcare%20Variation%202021_Full%20publication.pdf (viewed Jan 2022).

- 7. Yang IA, Brown JL, George J, et al. COPD‐X Australian and New Zealand guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2017 update. Med J Aust 2017; 207: 436‐442. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2017/207/10/copd‐x‐australian‐and‐new‐zealand‐guidelines‐diagnosis‐and‐management‐chronic

- 8. Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Ma P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and World Health Organization Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD): executive summary. Respir Care 2001; 46: 798‐825.

- 9. Yang IA, Jenkins CR, Salvi S. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in never‐smokers: risk factors, pathogenesis, and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10:497‐511.

- 10. Bui DS, Lodge CJ, Burgess JA, et al. Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 535‐544.

- 11. Ferry OR, Huang YC, Masel PJ, et al. Diagnostic approach to chronic dyspnoea in adults. J Thorac Dis 2019; 11 (Suppl): S2117‐S2128.

- 12. Liang J, Abramson MJ, Zwar NA, et al. Diagnosing COPD and supporting smoking cessation in general practice: evidence–practice gaps. Med J Aust 2018; 208: 29‐34. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2018/208/1/diagnosing‐copd‐and‐supporting‐smoking‐cessation‐general‐practice‐evidence

- 13. McDonald VM, Fingleton J, Agusti A, et al. Treatable traits: a new paradigm for 21st century management of chronic airway diseases: Treatable Traits Down Under International Workshop report. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1802058.

- 14. Duszyk K, McLoughlin RF, Gibson PG, McDonald VM. The use of treatable traits to address COPD complexity and heterogeneity and to inform the care. Breathe (Sheff) 2021; 17: 210118.

- 15. Alison JA, McKeough ZJ, Johnston K, et al; Lung Foundation Australia; Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Pulmonary rehabilitation guidelines. Respirology 2017; 22: 800‐819.

- 16. Wuytack F, Devane D, Stovold E, et al. Comparison of outpatient and home‐based exercise training programmes for COPD: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Respirology 2018; 23: 272‐283.

- 17. Ryrsø CK, Godtfredsen NS, Kofod LM, et al. Lower mortality after early supervised pulmonary rehabilitation following COPD‐exacerbations: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2018; 18: 154.

- 18. Ngai SP, Jones AY, Tam WW. Tai Chi for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (6): CD009953.

- 19. de Lima FF, Cavalheri V, Silva BSA, et al. Elastic resistance training produces benefits similar to conventional resistance training in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Phys Ther 2020; 100: 1891‐1905.

- 20. Vasilopoulou M, Papaioannou AI, Kaltsakas G, et al. Home‐based maintenance tele‐rehabilitation reduces the risk for acute exacerbations of COPD, hospitalisations and emergency department visits. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1602129.

- 21. Tsai LL, McNamara RJ, Moddel C, et al. Home‐based telerehabilitation via real‐time videoconferencing improves endurance exercise capacity in patients with COPD: the randomized controlled TeleR Study. Respirology 2017; 22: 699‐707.

- 22. Cheng SWM, McKeough Z, Alison J, et al. Associations of total and type‐specific physical activity with mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population‐based cohort study. BMC Public Health 2018; 18: 268.

- 23. Maddocks M, Kon SSC, Canavan JL, et al. Physical frailty and pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD: a prospective cohort study. Thorax 2016; 71: 988‐995.

- 24. Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 2021 report. https://goldcopd.org/wp‐content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD‐REPORT‐2021‐v1.1‐25Nov20_WMV.pdf (viewed Dec 2021).

- 25. Yang IA, George J, McDonald CF, et al. The COPD‐X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Version 2.63, February 2021. https://copdx.org.au/ (viewed Aug 2021).

- 26. Lahousse L, Verhamme KM, Stricker BH, Brusselle GG. Cardiac effects of current treatments of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 149‐164.

- 27. Chen WC, Huang CH, Sheu CC, et al. Long‐acting beta2‐agonists versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonists in patients with stable COPD: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Respirology 2017; 22: 1313‐1319.

- 28. Mammen MJ, Pai V, Aaron SD, et al. Dual LABA/LAMA therapy versus LABA or LAMA monotherapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review and meta‐analysis in support of the American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020; 17: 1133‐1143.

- 29. Mammen MJ, Lloyd DR, Kumar S, et al. Triple therapy versus dual or monotherapy with long‐acting bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020; 17: 1308‐1318.

- 30. Du Q, Jin J, Liu X, Sun Y. Bronchiectasis as a comorbidity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. PloS One 2016; 11: e0150532.

- 31. Salpeter S, Ormiston T, Salpeter E. Cardioselective beta‐blockers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (4): CD003566.

- 32. Dransfield MT, McAllister DA, Anderson JA, et al. β‐Blocker therapy and clinical outcomes in patients with moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heightened cardiovascular risk. An observational substudy of SUMMIT. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 608‐614.

- 33. Kakoullis L, Sampsonas F, Karamouzos V, et al. The impact of osteoporosis and vertebral compression fractures on mortality and association with pulmonary function in COPD: a meta‐analysis. Joint Bone Spine 2022; 89: 105249.

- 34. Aryal S, Diaz‐Guzman E, Mannino DM. Influence of sex on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk and treatment outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 9: 1145‐1154.

- 35. Gudmundsson G, Gislason T,Janson C, et al. Risk factors for rehospitalisation in COPD: role of health status, anxiety and depression. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 414‐419.

- 36. Chaouat A, Weitzenblum E, Krieger J, et al. Association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 151: 82‐86.

- 37. Shawon MSR, Perret JL, Senaratna CV, et al. Current evidence on prevalence and clinical outcomes of co‐morbid obstructive sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2017; 32: 58‐68.

- 38. Chang AB, Bell SC, Torzillo PJ, et al. Chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis in children and adults in Australia and New Zealand Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand guidelines. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 130. https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2015/202/1/chronic‐suppurative‐lung‐disease‐and‐bronchiectasis‐children‐and‐adults

- 39. Hurst JR, Elborn JS, De Soyza A. COPD‐bronchiectasis overlap syndrome. Eur Respir J 2015; 45: 310‐313.

- 40. Spece LJ, Epler EM, Donovan LM, et al. Role of comorbidities in treatment and outcomes after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018; 15: 1033‐1038.

- 41. Feary JR, Rodrigues LC, Smith CJ, et al. Prevalence of major comorbidities in subjects with COPD and incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke: a comprehensive analysis using data from primary care. Thorax 2010; 65: 956‐962.

- 42. Herth FJF, Slebos DJ, Criner GJ, Shah PL. Endoscopic lung volume reduction: an expert panel recommendation — update 2017. Respiration 2017; 94: 380‐388.

- 43. van Geffen WH, Slebos DJ, Herth FJ, et al. Surgical and endoscopic interventions that reduce lung volume for emphysema: a systemic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019; 7: 313‐324.

- 44. Fletcher C, Peto R. The natural history of chronic airflow obstruction. Br Med J 1977; 1: 1645‐1648.

- 45. Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, et al. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (5): CD000165.

- 46. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical‐resources/clinical‐guidelines/key‐racgp‐guidelines/view‐all‐racgp‐guidelines/supporting‐smoking‐cessation (viewed Jan 2022).

- 47. Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; (5): CD009329.

- 48. Kopsaftis Z, Wood‐Baker R, Poole P. Influenza vaccine for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; (6): CD002733.

- 49. Walters JA, Tang JN, Poole P, Wood‐Baker R. Pneumococcal vaccines for preventing pneumonia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; (1): CD001390.

- 50. Cross AJ, Thomas D, Liang J, et al. Educational interventions for health professionals managing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022; (5): CD012652.

- 51. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet 1981; 1: 681‐686.

- 52. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Ann Intern Med 1980; 93: 391‐398.

- 53. Long‐Term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group; Albert RK, Au DH, Blackford AL, et al. A randomized trial of long‐term oxygen for COPD with moderate desaturation. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1617‐1627.

- 54. Lacasse Y, Sériès F, Corbeil F, et al. Randomized trial of nocturnal oxygen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1129‐1138.

- 55. Ameer F, Carson KV, Usmani ZA, Smith BJ. Ambulatory oxygen for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who are not hypoxaemic at rest. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (6): CD000238.

- 56. Bradley JM, O’Neill B. Short term ambulatory oxygen for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; (4): CD004356.

- 57. Herath SC, Normansell R, Maisey S, Poole P. Prophylactic antibiotic therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; (10): CD009764.

- 58. Janjua S, Mathioudakis AG, Fortescue R, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; (1): CD013198.

- 59. Donovan T, Milan SJ, Wang R, et al. Anti‐IL‐5 therapies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; (12): CD013432.

- 60. Smallwood N, Ross L, Taverner J, et al. A palliative approach is adopted for many patients dying in hospital with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. COPD 2018; 15: 503‐511.

- 61. Verberkt CA, van den Beuken‐van Everdingen MHJ, Schols J, et al. Effect of sustained‐release morphine for refractory breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on health status: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2020; 180: 1306‐1314.

- 62. Raveling T, Vonk J, Struik FM, et al. Chronic non‐invasive ventilation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; (8): CD002878.

- 63. Jolly K, Majothi S, Sitch AJ, et al. Self‐management of health care behaviors for COPD: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 305‐326.

- 64. Jonkman NH, Westland H, Trappenburg JC, et al. Do self‐management interventions in COPD patients work and which patients benefit most? An individual patient data meta‐analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016; 11: 2063‐2074.

- 65. Jonkman NH, Westland H, Trappenburg JC, et al. Characteristics of effective self‐management interventions in patients with COPD: individual patient data meta‐analysis. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 55‐68.

- 66. Majothi S, Jolly K, Heneghan NR, et al. Supported self‐management for patients with COPD who have recently been discharged from hospital: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015; 10: 853‐867.

- 67. Zwerink M, Effing T, Kerstjens HA, et al. Cost‐effectiveness of a community‐based exercise programme in COPD self‐management. COPD 2016; 13: 214‐223.

- 68. Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. Effect of a hospital‐initiated program combining transitional care and long‐term self‐management support on outcomes of patients hospitalized with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 322: 1371‐1380.

- 69. Sanchis J, Gich I, Pedersen S; Aerosol Drug Management Improvement Team (ADMIT). Systematic review of errors in inhaler use: has patient technique improved over time? Chest 2016; 150: 394‐406.

- 70. Bosnic‐Anticevich S, Chrystyn H, Costello RW, et al. The use of multiple respiratory inhalers requiring different inhalation techniques has an adverse effect on COPD outcomes. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017; 12: 59‐71.

- 71. van Boven JFM, Chavannes NH, van der Molen T, et al. Clinical and economic impact of non‐adherence in COPD: a systematic review. Respir Med 2014; 108: 103‐113.

- 72. Howcroft M, Walters EH, Wood‐Baker R, Walters JA. Action plans with brief patient education for exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (12): CD005074.

- 73. Benzo R, Vickers K, Novotny PJ, et al. Health coaching and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease rehospitalization. A randomized study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194: 672‐680.

- 74. Soriano JB, García‐Río F, Vázquez‐Espinosa E, et al. A multicentre, randomized controlled trial of telehealth for the management of COPD. Respir Med 2018; 144: 74‐81.

- 75. Lavesen M, Ladelund S, Frederiksen AJ, et al. [Nurse‐initiated telephone follow‐up on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease improves patient empowerment, but cannot prevent readmissions] [Dutch]. Dan Med J 2016; 63.

- 76. Rose L, Istanboulian L, Carriere L, et al. Program of integrated care for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and multiple comorbidities (PIC COPD+): a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1701567.

- 77. Walker PP, Pompilio PP, Zanaboni P, et al. Telemonitoring in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (CHROMED). A randomized clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 198: 620‐628.

- 78. Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1128‐1138.

- 79. Han MK, Quibrera PM, Carretta EE, et al. Frequency of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Respir Med 2017; 5: 619‐626.

- 80. Lindenauer PK, Dharmarajan K, Qin L, et al. Risk trajectories of readmission and death in the first year after hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: 1009‐1017.

- 81. Couturaud F, Bertoletti L, Pastre J, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary embolism among patients with COPD hospitalized with acutely worsening respiratory symptoms. JAMA 2021; 325: 59‐68.

- 82. van Geffen WH, Douma WR, Slebos DJ, Kerstjens HAM. Bronchodilators delivered by nebuliser versus pMDI with spacer or DPI for exacerbations of COPD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; (8): CD011826.

- 83. Bardsley G, Pilcher J, McKinstry S, et al. Oxygen versus air‐driven nebulisers for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Pulm Med 2018; 18: 157.

- 84. Walters JA, Tan DJ, White CJ, Wood‐Baker R. Different durations of corticosteroid therapy for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; (3): CD006897.

- 85. Walters JAE, Tan DJ, White CJ, et al. Systemic corticosteroids for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (9): CD001288.

- 86. Sivapalan P, Ingebrigtsen TS, Rasmussen DB, et al. COPD exacerbations: the impact of long versus short courses of oral corticosteroids on mortality and pneumonia: nationwide data on 67 000 patients with COPD followed for 12 months. BMJ Open Respir Res 2019; 6: e000407.

- 87. Therapeutic Guidelines. Antibiotic: version 16. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited, 2019. https://www.tg.org.au/ (viewed Jan 2022).

- 88. Barnett A, Beasley R, Buchan C, et al. Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand position statement on acute oxygen use in adults: “Swimming between the flags”. Respirology 2022; doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14218.

- 89. Austin MA, Wills KE, Blizzard L, et al. Effect of high flow oxygen on mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in prehospital setting: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 341: c5462.

- 90. Osadnik CR, Tee VS, Carson‐Chahhoud KV, et al. Non‐invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; (7): CD004104.

Abstract

Introduction: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a treatable and preventable disease characterised by persistent respiratory symptoms and chronic airflow limitation on spirometry. COPD is highly prevalent and is associated with exacerbations and comorbid conditions. “COPD‐X” provides quarterly updates in COPD care and is published by the Lung Foundation Australia and the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand.

Main recommendations: The COPD‐X guidelines (version 2.65) encompass 26 recommendations addressing:

Changes in management as a result of these guidelines: Both non‐pharmacological and pharmacological strategies are included within these recommendations, reflecting the importance of a holistic approach to clinical care for people living with COPD to delay disease progression, optimise quality of life and ensure best practice care in the community and hospital settings when managing exacerbations. Several of the new recommendations, if put into practice in the appropriate circumstances, and notwithstanding known variations in the social determinants of health, could improve quality of life and reduce exacerbations, hospitalisations and mortality for people living with COPD.