Gender‐based violence includes physical, psychological, sexual or economic behaviour causing harm for reasons associated with people’s gender.1 A violation of human rights, women are disproportionately affected by gender‐based violence,2 with Indigenous women and girls facing particularly high risk.3 Globally, the gender‐based violence types most widely studied are domestic and sexual violence, with 35% of women worldwide experiencing either or both during their lifetime.2 Australian national studies show domestic violence occurs against one in six women and one in 17 men,4 and sexual violence occurs against one in six women (mostly by someone they know) and against one in 25 men.5 Australian Indigenous women’s experiences are 35–80 times the national average.6 Women victims/survivors experience greater fear, injuries, chronic mental and physical health issues compared with men victims/survivors, resulting in a large burden of disease, especially for childbearing women.2,7 While national prevalence data and evidence about response for people in same‐sex relationships, non‐binary or transgender individuals are lacking,8 global studies suggest high rates of both domestic and sexual violence for these groups.9,10,11 This narrative review concentrates on domestic and sexual violence against cisgender women by men, with a particular focus on Indigenous women, who the United Nations reports experience the highest levels of violence in Australia.3

Structural inequities underpin domestic and sexual violence across which a culture of power, control and silence permeates, impeding the safety of women and undervaluing their agency and resistance.12 Built on a foundation of patriarchal colonialism, Australia’s value system and, therefore, its service systems are inextricably bound to structures of power and oppression that subjugate Indigenous women.12 Across these systems, there remains a deficit‐focused victim‐blaming narrative regarding women experiencing domestic and/or sexual violence, resulting in women’s trust in services being sparse. Racism, lack of gender‐focused attention and purposeful othering are additional inequities that Indigenous women face, resulting in their pathologisation and/or criminalisation, and obscuring nuanced aspects of their lived experience.12 Under‐resourcing, lack of research and inadequate legislation, all operate to compound the silencing of women’s voices. Indigenous women’s voices are the least heard, compromising their safety, and that of their children, at alarming rates.13

In this narrative review, we focus on the health system, as victims/survivors are more likely to access health services (eg, general practice, sexual health, mental health, emergency care, Aboriginal community‐controlled health services and maternity services) than any other professional help.4,14 Health practitioners are ideally placed to identify domestic and sexual violence, provide a first line response, and refer on to support services. However, domestic and sexual violence continue to be under‐recognised and poorly addressed by health practitioners.14,15,16,17 Indigenous women’s help‐seeking is particularly compromised, with numerous complexities regarding Indigenous‐specific services and the unresponsiveness of mainstream services.12,18 It is essential for practitioners to have the skills to ask and respond to domestic and sexual violence, given that victims/survivors who receive positive reactions are more likely to accept help. In this review, we present the evidence and expert recommendations over the past decade on how to recognise domestic and sexual violence in practice and respond to victims/survivors. In addition, we briefly outline the importance of also addressing the needs of people who use domestic and sexual violence and children exposed to domestic violence.

We performed a search of databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, SocINDEX and ATSIhealth) for systematic review articles and international guidelines from 2012 to 2022. This enabled us to formulate a current evidence‐based overview as applied to identification and response to domestic and sexual violence in health settings. Additional review articles were identified via our own professional knowledge and reference checking.

Barriers to inquiry and disclosure

There are many barriers to inquiry by health practitioners and disclosure by victims/survivors.19,20,21 A systematic review of 35 quantitative studies suggested low rates of routine domestic violence screening by practitioners (with the majority reporting between 10% and 20%)22 From meta‐syntheses of qualitative studies, we know that health practitioners experience personal and structural barriers to domestic violence inquiry and response. Personal barriers include practitioners feeling they “can’t interfere” as domestic and sexual violence are private issues, “don’t have control” over outcomes for victims/survivors, and “won’t take responsibility” as it is someone else’s role.20 At the structural level, practitioners perceive that “the environment works against us” with lack of time and spaces, they are “trying to tackle the problem on their own” without a team behind them, and “societal beliefs enable us to blame the victim”.19 System‐level barriers, such as the presence of the partner in consultations or a lack of training or referral services, can impede practitioners even further.23 There were no specific reviews on sexual violence, but in the Australian mental health inpatient setting, some practitioners dismissed that sexual violence was an issue, some acknowledged it but felt unprepared, and others understood sexual violence but despaired of being able to respond in a gender‐sensitive way.24

From the patient’s viewpoint, there are many barriers to disclosure of gender‐based violence to health practitioners. In a systematic review, barriers related to practitioners included fears about consequences of disclosing (eg, children being removed), judgemental responses, or confidentiality being broken. Further barriers included not trusting practitioners, limited time, negative responses, or perception that practitioners were not competent.21 Personal barriers included shame, unawareness that what they were experiencing was abuse, or being socially entrapped (lack of finances and social support).21 In screening programs, only a small number of victims/survivors disclosed that they experienced domestic violence (3.7% in the New South Wales Health Domestic Violence Routine Screening program,25 2% in the South East Queensland Study,26 and 1.3% in the Victorian Maternal and Child Health27), with most women declining referral. For sexual violence, a systematic review of delayed disclosure in health settings reported barriers including a belief that it was irrelevant to the consultation, embarrassment or fear of judgement, or that the practitioner did not ask.28 For women experiencing sexual violence perpetrated by an intimate partner, additional barriers included not realising that the behaviour was abusive, social stigma, and fear of their partner.29

Disclosure rates in Indigenous communities are extremely low.30 Fears of reprisal by extended family, the justice system, and child removal by state services all influence disclosure.31,32 Silencing, shame and protective behaviour frequently have an impact on help‐seeking, which often only occurs at crisis points as a result of serious injury and life‐threatening experiences.18 Police responses of indifference or disbelief33 impede disclosure, and Indigenous women commonly experience their children being, or threatened to be, removed in domestic violence‐related service responses.32 This is experienced as another layer of violence that creates help‐seeking avoidance. Health practitioner responses to Indigenous patients often misunderstand equity with notions of “treating everyone the same” or “not seeing colour”.34 This perpetuates structural inequities that do not address the nuanced complexities of Indigenous women’s experiences, rather than working in ways that respect the cultural and gendered self‐determination of Indigenous women.

Asking about domestic and sexual violence in health settings

It is good clinical practice to inquire about domestic and sexual violence when a patient is alone and has a clinical indicator (eg, mental health issues, chronic pain, injuries, reproductive issues).35 In some settings (eg, alcohol, drug and mental health services), asking everybody attending is recommended, since all patients have indicators of underlying gender‐based violence. A Cochrane systematic review of universal domestic violence screening found two antenatal studies that showed improvement in outcomes for women; consequently, routine screening (without underlying indicators) is recommended only in antenatal care.36

Studies show the majority of women are comfortable being asked about domestic violence, provided that questions are asked in a non‐judgemental, sensitive way.36 Asking general questions about relationships followed by questions about behaviour (eg, hitting, controlling behaviour, humiliation) or feelings (eg, fear, unsafe) are more likely to elicit disclosures than asking stigmatising‐type questions (eg, “are you experiencing domestic or sexual violence?”).37 If domestic violence is disclosed, then asking specifically about sexual violence is suggested to elicit disclosure of these hidden experiences,38 although in some cultures sexual violence is a taboo subject.39,40 For Indigenous women, indirect questions and conversational interactions that are collaborative and responsive are recommended41 as more appropriate than direct questions. We found no studies exploring Indigenous women’s experiences of being asked about domestic violence in health settings but note cultural safety as a condition for disclosure and racism as a barrier.42

There is some evidence to suggest clinicians should ask more than once, since victims/survivors may not be ready to disclose at first.43,44 A systematic review of six trials45 showed that disclosure occurred at similar rates between face‐to‐face inquiry and written questionnaires; however, computer‐assisted screens demonstrated increased rates of domestic violence disclosure. A systematic review of ten domestic violence tools recommended three tools for clinical use: Women Abuse Screen Tool (WAST), Abuse Assessment Screen (AAS), and Humiliation, Afraid, Rape and Kick (HARK).46 These tools have had limited validation in culturally and linguistically diverse populations and in Indigenous populations. More recently, a new tool — ACTS (Afraid/Controlled/Threatened/Slapped or physically hurt) — showed high sensitivity and specificity when tested in antenatal care in English, Arabic and Chinese speaking populations.47 Far less is known about how women wish to be asked about sexual violence, with no systematic reviews addressing this topic.

Overall, a qualitative systematic review48 of what victims/survivors wanted from health practitioners around disclosure of domestic violence showed women wanted universal education, safe environments and sensitive enquiry (Box 1).

Responding in health settings

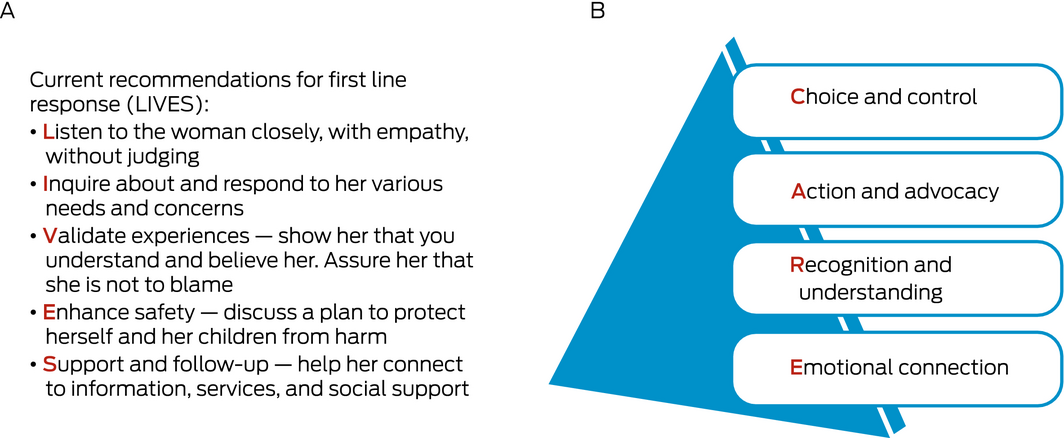

The World Health Organization recommends (based on systematic reviews) that all health practitioners be trained in first line response using the LIVES model (listening, inquiring about needs, validating experiences, enhancing safety and offering ongoing support; Box 2).14 A qualitative systematic review suggests how practitioners should approach women survivors using the CARE model (Box 2).16 This involves providing victims/survivors with choice and control, advocacy and practical action, recognising their experience, and connecting emotionally through kindness and empathy. Assessing risk and safety alongside understanding women’s readiness to take action are often the key new skills health practitioners need to acquire.49 Online responses, such as safety decision aids developed to assist, show mixed evidence but they can encourage women to self‐reflect and examine their relationships.50 Face‐to‐face and online responses need to understand that many victims/survivors may not wish to access formal domestic and sexual violence services as they do not self‐identify as experiencing domestic or sexual violence.51

Understanding the social, cultural and political contexts within which women seek help is also an important consideration. Many Indigenous women, women of colour, LGBTQIA2+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersexual, asexual and two‐spirited) people, and women with disability face intersecting oppressions that compound upon and reinforce one another.52 Few studies have specifically looked at Indigenous women’s help‐seeking behaviour for domestic and sexual violence in health settings. A scoping review18 and a qualitative evidence synthesis of Indigenous people’s experiences and expectations of practitioners when accessing care for domestic violence17 identified similar themes: relationship and trust building, cultural awareness and domestic violence training, and strengthening safety. Further, a critical interpretive synthesis of Indigenous mothering in the context of domestic violence identified service responsiveness to be characterised by continuity of care, a good understanding of domestic violence, relationality, being intuitive to help‐seeking patterns, and including help for children.12 A systematic review of Indigenous Australians and sexual violence found a significant lack of evidence on what works in responding to Indigenous women who experience sexual violence.33

Recovery and healing

In the longer term, Cochrane systematic reviews suggest that domestic violence advocacy programs53 (focusing on empowerment, safety and resources, including home visiting) and specific psychological treatments (cognitive behavioural therapy, trauma‐informed cognitive behavioural therapy) show some promise.54 In the context of sexual violence, reviews suggest that some survivors similarly benefit from psychological therapies such as cognitive processing therapy or eye‐movement desensitisation and reprocessing.55 However, others do not find these helpful or experience barriers to access,55 with rates of mental health care utilisation low among sexual violence survivors.56 Mind and body interventions such as yoga or mindfulness have shown some promise in reducing the negative health impacts of sexual violence,57 but as yet, the evidence base to support effectiveness is underdeveloped.

Safety and healing for Indigenous women is impeded by an absence of evidence‐informed models that centre Indigenous women’s voices and a failure to acknowledge gender in Indigenous women’s recovery and healing. Colonial narratives about gender‐based violence continue to dominate, with few Indigenous feminist perspectives available or being accorded the same visibility.32,58,59 Australian Indigenous women’s mental health, identity issues, mother–child relationships, housing and overall safety issues (including racism and child removal) can all be effectively considered by privileging their experiences and voices.12 Indigenous‐led models of recovery and healing are critical but require empirical research and Indigenous women’s engagement to inform them, and sound evaluation.

Responding to other members of the family

Many practitioners will be seeing other members of the family in addition to the victim/survivor.60 Exposure to domestic violence is seen as child abuse and neglect and as damaging as other forms of child abuse.61 Recognising signs and symptoms in children (behavioural, social, emotional, cognitive and physical) is essential to interrupt long term effects as adults.61 Children living with domestic violence need offers of individual and group work, including mother–child psychotherapeutic interventions.62,63 There remains a dearth of work exploring Indigenous children’s experience both as connected to their mothers’ experiences or as distinct victims/survivors themselves with unique needs. The behavioural, cognitive and emotional disadvantage experienced by children and the multilayered nature of disadvantage experienced by Indigenous children who live with domestic violence pose vulnerability to long term harmful impact.64

Health practitioners also need to work with individuals who use violence, especially men who are fathers, to reduce the impact on women and children. For men, systematic reviews report that using domestic violence is associated with increased alcohol and substance misuse, depression, suicide, anxiety, low self‐esteem, and use of health services.65,66 Consequently, men presenting with mental health issues provide an opportunity for trained practitioners to ask about what is happening in their relationships.67 A systematic review68 and meta‐analysis of six qualitative studies with men who had used violence reported several barriers to disclosure in health care settings, including fear of consequences and lack of trust in the health care provider’s ability to help. Facilitators of disclosure included feeling listened to by the health care practitioner and receiving offers of emotional or practical support. In terms of specific interventions, there is scant evidence to guide best practice for responding to perpetrators, with most research being done in the justice system context. A systematic review69 of ten interventions in health settings found only weak evidence for any intervention’s effectiveness, although interventions conducted concurrently with alcohol treatment show some promise. The efficacy of Indigenous‐specific programs aimed at addressing men’s violence against women is unconfirmed.70 A number of studies promote holistic, trauma‐informed approaches to working with Indigenous men but identify a lack of resourcing, sound infrastructure, and evaluation.71 The lack of an Indigenous feminist approach to much of the work identified with Indigenous men is also evident.71

Assisting health professionals to be ready to identify and respond to gender‐based violence

Specific factors increasing a health practitioner’s likelihood of identifying gender‐based violence include having scripted questions, recognising silent cues, interdisciplinary collaboration and access to resources and referrals.72 Intersectoral partnerships and local community solutions are enablers for Indigenous women.33 Practitioners need assistance to become physically, culturally and emotionally equipped to undertake this sensitive work. Further, being able to identify and respond to Indigenous women, with particular readiness to consider their unique intersectional disadvantage and oppression, is important.

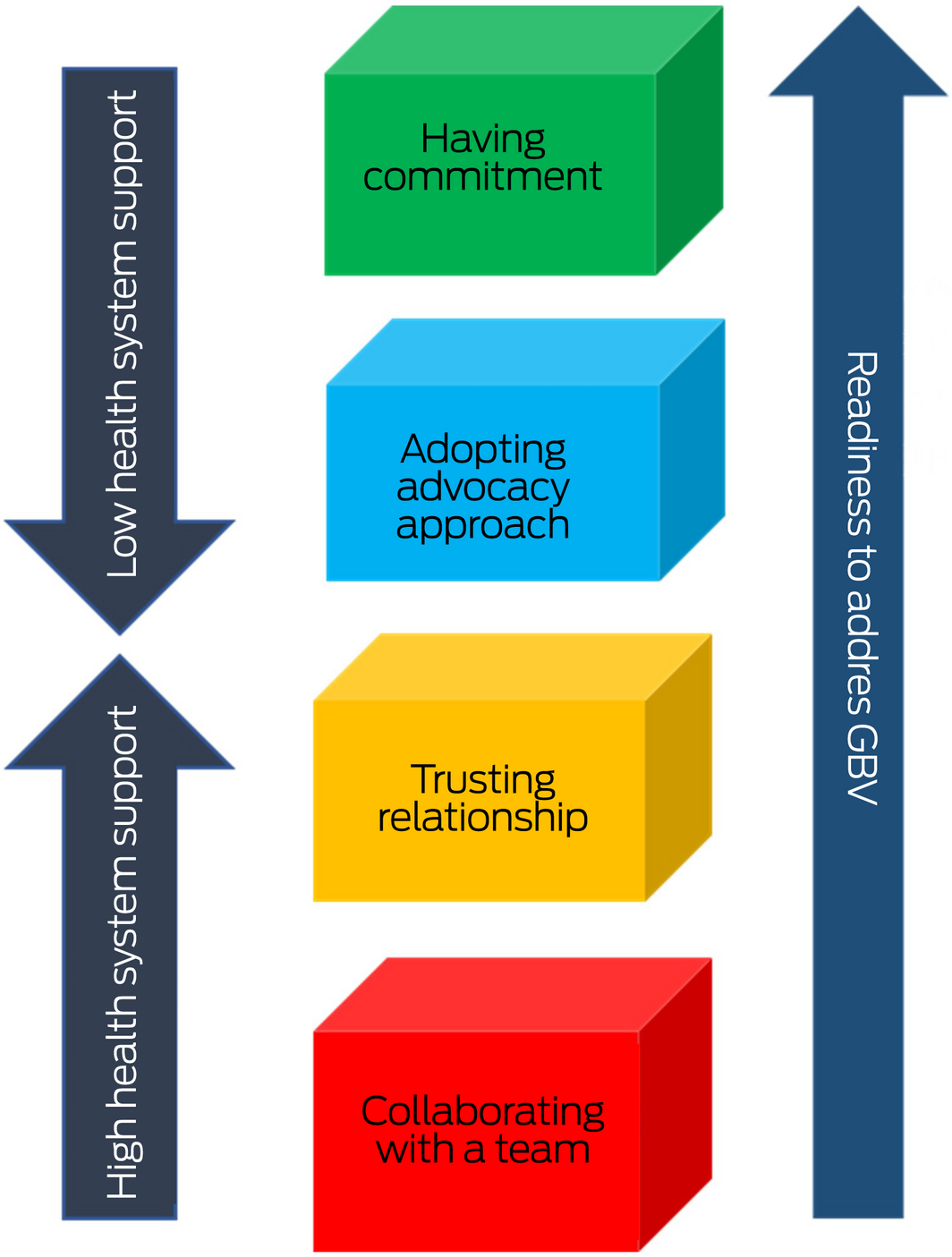

A qualitative systematic review exploring health professionals’ readiness to address gender‐based violence highlights the factors and presents a model enabling practitioners to address domestic and sexual violence (Box 3).73 The model suggests that when practitioners are motivated by a human or children rights perspective, feminist lens or a personal experience of gender‐based violence, their commitment to address gender‐based violence is enhanced. If practitioners employ a survivor‐centred or advocacy approach, and get positive feedback, this encourages health practitioners to trust that the clinical setting is ideal for responding to gender‐based violence. Collaborating with a team, including with specialist professionals, can also increase readiness. However, strong health systems support needs to underpin all these elements to facilitate practitioner engagement with the work to address gender‐based violence.73 The CATCH model (Commitment, Advocacy, Trust, Collaboration, Health system support) could assist educators training practitioners to pay attention to readiness factors, and could assist workplaces to strengthen health system support for workers.

System support

Comprehensive health system changes need to occur to improve patient outcomes, rather than specific aspects in isolation (eg, training of staff or introduction of polices alone).15 A Cochrane review showed domestic violence training might affect practitioners’ attitudes to victims/survivors, but there is very limited evidence that it leads to improvements in identification, safety planning, or referral.74 For responses to be effective with Indigenous women, significant systems change is required, as there is considerable evidence that demonstrates racism within the health system.75 Support for health professionals to effectively respond requires both cultural safety and antiracism training, and inclusion of Indigenous women’s voices and needs to be tailored to context.76 These are framed by the Australian Human Rights Commission’s recent report, Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices): securing our rights, securing our future, which has developed a framework for substantial system reform related to Indigenous women’s voice, representation and participation across a number of domains. These support a broader human rights framework for systems change which has as its foundation trauma‐informed gender equity.13

The WHO,15 based on consensus guidelines globally, has outlined what is needed at the systems level to support practitioners in doing gender‐based violence work. A survey of health clinics across Europe found several factors were key to making gender‐based violence work sustainable: committed leadership, regular training (with mandatory attendance) of staff from front‐desk workers to health practitioners, use of the trainer model with on‐site trainers, and a clear referral pathway.77 Box 4 brings together these guidelines,15 factors,77 and Indigenous women’s requirements76 to represent a trauma‐ and violence‐informed system approach that is gender‐responsive, culturally safe and contextually tailored.

Using trauma‐, violence‐ and gender‐informed care approaches

A whole‐of‐system approach requires embedding principles of trauma‐ and violence‐informed care into practice (Box 5).78,79 In addition, a gender lens is critical to applying this framework in the context of gender‐based violence. This includes recognising connections between gender‐based violence, trauma and negative health outcomes, enhancing safety and minimising potential for retraumatisation for patients and staff.81 However, there have been very few evaluations of such approaches.82

In codesigning a complex trauma assessment tool for Indigenous parents, the authors of a 2020 article identified six prerequisites for considering the safety of discussions about complex trauma (Box 6).83

This work identifies considerations of engaging in sensitive conversations with Indigenous peoples. While acknowledged as important, strong concerns were expressed through Indigenous community codesign workshops regarding where, by whom and how such conversations occur.83 Trauma‐ and violence‐informed care approaches appropriate for Indigenous women are largely absent or not evaluated. This is a critical area of development.

Conclusion

In this article, we have outlined the evidence supporting the key role of health systems in addressing the challenge of gender‐based violence against cisgender women by men, in particular, domestic and sexual violence. Gender‐based violence is a major cause of mental ill health, hospitalisation, death, chronic pain and injury,2 with annual costs in Australia estimated at $21.7 billion.84 For too long, this social condition has been seen as the domain of social services or justice, with policy failing to resource an integrated response by the health system. The unfortunate consequences of this lack of recognition and resourcing of health settings is that many victims/survivors, children exposed to domestic violence, and people who use domestic or sexual violence have remained unidentified or inadequately supported.

The need for greater attention to Indigenous women’s voices in moving forward is evident. The complexities and intersecting oppressions women face remain unrecognised and not addressed in a confusion of theories, policy and practice, and a lack of Indigenous women‐centred research. The unresolved and cumulative trauma is having an unprecedented impact on the psychological health of Indigenous women who experience domestic or sexual violence, among other forms of violence.13 Indigenous women’s lives matter and the health care system has a responsibility to offer evidence‐based care that responds to gender‐based violence in ways that heed Indigenous women’s lived experience.

Health practitioners are in an ideal position to recognise gender‐based violence, ask through sensitive inquiry, assess risk, provide a first line response, and contribute to ongoing responses to enable pathways to safety, health and wellbeing.15 System support through committed leadership, specific policies and protocols tailored to context, clinical champions, infrastructure, and quality improvement activities is essential. We still have a long way to go before these evidence‐based recommendations, comprehensively outlined in the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ White Book,85 are implemented in practice.

Box 1 – Expectations of women about disclosure of domestic violence to health professionals48

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Provide universal education, including around dynamics of abuse and violence and warning signs, health impacts on themselves and their children, and options for assistance. Women emphasised information should be given routinely to avoid patients feeling stigmatised or singled out, and to provide all women with an understanding of domestic and sexual violence irrespective of their personal experiences. Provision of information was perceived as being an important precursor to sensitive enquiry by the health practitioner. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Create a safe and supportive environment for disclosure, including reassurance that the woman is not risking retaliation by the perpetrator or that her children will be removed if she discloses, and making women feel that they will not be judged. |

|||||||||||||||

|

Ask questions in an appropriate context and with sensitive timing, after building rapport, including using language that is friendly, non‐judgemental and inclusive of all forms of abuse, and using a combination of direct and indirect questions. Using the woman’s health or that of her children as a way to initiate a conversation about domestic violence was suggested as one way to approach the topic. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 – The (A) LIVES and (B) CARE models for first line response to domestic and sexual violence16,35

Box 3 – CATCH model: what factors increase practitioner readiness to respond to gender‐based violence (GBV)73

Box 4 – System model for factors needed to support health practitioners to address domestic and sexual violence

GBV = gender‐based violence. [◆

Box 5 – Guiding principles of trauma‐ and violence‐informed care80

|

Principles |

Description |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Safety (physical, emotional, spiritual and cultural safety) |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Trustworthiness and transparency |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Peer support |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Collaboration and mutuality |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Empowerment, voice and choice |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Respect for diversity and inclusiveness |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Strengths‐based and skill‐building approach |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 6 – Prerequisites for discussion about complex trauma for Indigenous parents in the perinatal setting83

- Emotional, physical and cultural safety must be clearly established.

- A trusting relationship with the person talking about complex trauma is critical. Relational vulnerabilities underpin trauma and can have an impact on readiness to trust. Time is taken to build trust and establish relationships or involve people who have established a trusting relationship.

- Must have the capacity to respond effectively, including being able to “hold the space”, have time to listen, and identify the skills and support services available. This may involve collaboration with a range of holistic clinical and non‐clinical support options.

- Incorporate cultural methods of communication gently and indirectly to understand the effects of trauma, including the likelihood that parents may be using avoidance as a coping strategy.

- Use strengths‐based approaches and offer choices to empower parents, normalise complex trauma responses and affirm hopes and dreams for their family.

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- Kelsey L Hegarty1,2

- Shawana Andrews1,3

- Laura Tarzia1,2

- 1 Safer Families Centre, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

- 2 Centre for Family Violence Prevention, Royal Women’s Hospital, Melbourne, VIC

- 3 Melbourne Poche Centre for Indigenous Health, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC

Open access

Open access publishing facilitated by The University of Melbourne, as part of the Wiley ‐ The University of Melbourne agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

The Safer Families Centre is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) grant No. 1116690. The NHMRC did not have any role in the planning, writing or publication of the work.

No relevant disclosures.

- 1. Council of Europe. Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence [CETS No. 210]. http://www.conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/QueVoulezVous.asp?CL=ENG&NT=210 (viewed June 2022).

- 2. World Health Organization. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non‐partner sexual violence. WHO, 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/9789241564625_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (viewed June 2022).

- 3. Manjoo R. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, its causes and consequences. Human Rights Council, 20th Session. United Nations; 2012. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/A.HRC.20.16_En.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 4. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018 [Cat. No. FDV 2]. Canberra: AIHW; 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic‐violence/family‐domestic‐sexual‐violence‐in‐australia‐2018/summary (viewed June 2022).

- 5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Sexual assault in Australia. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/0375553f‐0395‐46cc‐9574‐d54c74fa601a/aihw‐fdv‐5.pdf.aspx?inline=true (viewed June 2022).

- 6. Spinney A. FactCheck Q&A: are Indigenous women 34–80 times more likely than average to experience violence? The Conversation 2016; 4 July. https://theconversation.com/factcheck‐qanda‐are‐indigenous‐women‐34‐80‐times‐more‐likely‐than‐average‐to‐experience‐violence‐61809 (viewed June 2022).

- 7. Ayre J, Lum On M, Webster K, et al. Examination of the burden of disease of intimate partner violence against women in 2011: final report [ANROWS Horizons, no. 06/2016]. Sydney: ANROWS, 2016. https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/examination‐of‐the‐burden‐of‐disease‐of‐intimate‐partner‐violence‐against‐women‐in‐2011‐final‐report/ (viewed June 2022).

- 8. Victorian Agency for Health Information. The health and wellbeing of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer population in Victoria: findings from the Victorian Population Health Survey 2017. Melbourne: VAHI, 2020. https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020‐09/The‐health‐and‐wellbeing‐of‐the‐LGBTIQ‐population‐in‐Victoria.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 9. Brown TNT, Herman JL. Intimate partner violence and sexual abuse among LGBT people: a review of existing research. Los Angeles: Williams Institute, University of California; 2015. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/ipv‐sex‐abuse‐lgbt‐people/ (viewed June 2022).

- 10. Walters ML, Chen J, Breiding MJ. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 findings on victimization by sexual orientation. Atlanta: National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_sofindings.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 11. Peitzmeier SM, Malik M, Kattari SK, et al. Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: systematic review and meta‐analysis of prevalence and correlates. Am J Public Health 2020; 110: e1‐e14.

- 12. Andrews S, Hamilton B, Humphreys C. A global silence: a critical interpretive synthesis of Aboriginal mothering through domestic and family violence. Affilia 2021; doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/08861099211055520.

- 13. Australian Human Rights Commission. Wiyi Yani U Thangani (women’s voices): securing our rights, securing our future — report. Australian Human Rights Commission, 2020. https://humanrights.gov.au/our‐work/aboriginal‐and‐torres‐strait‐islander‐social‐justice/publications/wiyi‐yani‐u‐thangani (viewed June 2022).

- 14. World Health Organization. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines. WHO, 2013. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85240/9789241548595_eng.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 15. García‐Moreno C, Hegarty K, d’Oliveira AFL, et al. The health‐systems response to violence against women. Lancet 2015; 385: 1567‐1579.

- 16. Tarzia L, Bohren M, Cameron J, et al. Women’s experiences and expectations after disclosure of intimate partner abuse to a healthcare provider: a qualitative meta‐synthesis. BMJ Open 2020; 10: e041339.

- 17. Fiolet R, Cameron J, Tarzia L, et al. Indigenous people’s experiences and expectations of health care professionals when accessing care for family violence: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022; 23: 567‐580.

- 18. Fiolet R, Tarzia L, Hameed M, Hegarty K. Indigenous peoples’ help‐seeking behaviors for family violence: a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2021; 22: 370‐380.

- 19. Hudspeth N, Cameron J, Baloch S, et al. Health practitioners’ perceptions of structural barriers to the identification of intimate partner abuse: a qualitative meta‐synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res 2022; 22: 96.

- 20. Tarzia L, Cameron J, Watson J, et al. Personal barriers to addressing intimate partner abuse: a qualitative meta‐synthesis of healthcare practitioners’ experiences. BMC Health Serv Res 2021; 21: 567.

- 21. Heron RL, Eisma MC. Barriers and facilitators of disclosing domestic violence to the healthcare service: A systematic review of qualitative research. Health Soc Care Community 2020; 29: 612‐630.

- 22. Alvarez C, Fedock G, Grace KT, Campbell J. Provider screening and counseling for intimate partner violence: a systematic review of practices and influencing factors. Trauma Violence Abuse 2017; 18: 479‐495.

- 23. Sprague S, Madden K, Simunovic N, et al. Barriers to screening for intimate partner violence. Women Health. 2012; 52: 587‐605.

- 24. O’Dwyer C, Tarzia L, Fernbacher S, Hegarty K. Health professionals’ experiences of providing care for women survivors of sexual violence in psychiatric inpatient units. BMC Health Servi Res 2019; 19: 839.

- 25. NSW Ministry of Health. Domestic violence routine screening; November 2015 — snapshot 13. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health, 2016. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/parvan/DV/Documents/dvrs‐snapshot‐report‐13‐2015.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 26. Baird K, Creedy DK, Saito AS, Eustace J. Longitudinal evaluation of a training program to promote routine antenatal enquiry for domestic violence by midwives. Women Birth 2018; 31: 398‐406.

- 27. Hooker L, Nicholson J, Hegarty K, et al. Victorian Maternal and Child Health nurses’ family violence practices and training needs: a cross‐sectional analysis of routine data. Aust J Prim Health 2021; 27: 43‐49.

- 28. Lanthier S, Du Mont J, Mason R. Responding to delayed disclosure of sexual assault in health settings: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018; 19: 251‐265.

- 29. Wright E, Anderson J, Phillips K, Miyamoto S. Help‐seeking and barriers to care in intimate partner sexual violence: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2021; doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838021998305 [Epub ahead of print].

- 30. Willis M. Non‐disclosure of violence in Australian Indigenous communities. Trends and Issues in Crime and Criminal Justice [No. 405]. Australian Institute of Criminology, 2011. https://www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi405 (viewed June 2022).

- 31. Cripps K, Adams M. Chapter 23: Indigenous family violence: pathways forward. In: Walker R, Dudgeon P, Milroy H; editors. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice. Canberra: Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, 2014.

- 32. Langton M, Smith K, Eastman T, et al. Improving family violence legal and support services for Indigenous women. ANROWS, 2020. https://www.anrows.org.au/project/improving‐family‐violence‐legal‐and‐support‐services‐for‐indigenous‐women/ (viewed June 2022).

- 33. McCalman J, Bridge F, Whiteside M, et al. Responding to Indigenous Australian sexual assault: a systematic review of the literature. SAGE Open 2014; doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013518931.

- 34. Karmali F, Kawakami K, Vaccarino E, et al. I don’t see race (or conflict): strategic descriptions of ambiguous negative intergroup contexts. Journal of Social Issues 2019; 75: 1002‐1034.

- 35. World Health Organization. Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence: a clinical handbook. WHO, 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/136101/1/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 36. O’Doherty L, Hegarty K, Ramsay J, et al. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (7): CD007007.

- 37. Koss M. Revising the SES: a collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychol Women Q 2007; 31: 357‐370.

- 38. Tarzia L, Hegarty K. “He’d tell me i was frigid and ugly and force me to have sex with him anyway”: women’s experiences of co‐occurring sexual violence and psychological abuse in heterosexual relationships. J Interpers Violence 2022; doi: 10.1177/08862605221090563 [Epub ahead of print].

- 39. Probst DR, Turchik JA, Zimak E, Huckins JL. Assessment of sexual assault in clinical practice: available screening tools for use with different adult populations. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma 2011; 20: 199‐226.

- 40. Baloch S, Hameed M, Hegarty K. Health care providers views on identifying and responding to South Asian women experiencing family violence: a qualitative meta synthesis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022; doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211043829 [Epub ahead of print].

- 41. Putt J, Holder R, O’Leary C. Women’s specialist domestic and family violence services: their responses and practices with and for Aboriginal women: key findings and future directions. Sydney: ANROWS, 2017. https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/womens‐specialist‐domestic‐and‐family‐violence‐services‐their‐responses‐and‐practices‐with‐and‐for‐aboriginal‐women‐key‐findings‐and‐future‐directions/ (viewed June 2022).

- 42. Spangaro J, Herring S, Koziol‐Mclain J, et al. “They aren’t really black fellas but they are easy to talk to”: factors which influence Australian Aboriginal women’s decision to disclose intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Midwifery 2016; 41: 79‐88.

- 43. O’Reilly R, Beale B, Gillies D. Screening and intervention for domestic violence during pregnancy care: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010; 11: 190‐201.

- 44. Spangaro J, Zwi AB, Poulos R. The elusive search for definitive evidence on routine screening for intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2009; 10: 55‐68.

- 45. Hussain N, Sprague S, Madden K, et al. A comparison of the types of screening tool administration methods used for the detection of intimate partner violence: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 2015; 16: 60‐69.

- 46. Arkins B, Begley C, Higgins A. Measures for screening for intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2016; 23: 217‐235.

- 47. Hegarty K, Spangaro J, Koziol‐McLain J, et al. Sustainability of identification and response to domestic violence in antenatal care: The SUSTAIN Study. ANROWS, 2020. https://www.anrows.org.au/publication/sustainability‐of‐identification‐and‐response‐to‐domestic‐violence‐in‐antenatal‐care/ (viewed June 2022).

- 48. Korab‐Chandler E, Kyei‐Onanjiri M, Cameron J, et al. Women’s experiences and expectations of intimate partner abuse identification in healthcare settings: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2022. In press.

- 49. Hegarty K, O’Doherty LJ, Gunn JM, et al. A brief counselling intervention by health professionals utilising the ‘readiness to change’ concept for women experiencing intimate partner abuse: the WEAVE project. J Fam Stud 2008; 14: 376‐388.

- 50. Hegarty K, Tarzia L, Valpied J, et al. An online healthy relationship tool and safety decision aid for women experiencing intimate partner violence (I‐DECIDE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 2019; 4: e301‐e310.

- 51. Hegarty K, O’Doherty L, Taft A, et al. Screening and counselling in the primary care setting for women who have experienced intimate partner violence (WEAVE): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013; 382: 249‐258.

- 52. Graaff K. The implications of a narrow understanding of gender‐based violence. Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics 2021; doi: https://doi.org/10.20897/femenc/9749.

- 53. Rivas C, Ramsay J, Sadowski L, et al. Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well‐being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (3): CD005043.

- 54. Hameed M, O’Doherty L, Gilchrist G, et al. Psychological therapies for women who experience intimate partner violence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; (7): CD013017.

- 55. Regehr C, Alaggia R, Dennis J, et al. Interventions to reduce distress in adult victims of sexual violence and rape: a systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2013; 9: 1‐133.

- 56. Price M, Davidson T, Ruggiero K, et al. Predictors of using mental health services after sexual assault. J Trauma Stress 2014; 27: 331‐337.

- 57. Nolan CR. Bending without breaking: a narrative review of trauma‐sensitive yoga for women with PTSD. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2016; 24: 32‐40.

- 58. McGlade H. Our greatest challenge: Aboriginal children and human rights. Aboriginal Studies Press, 2012.

- 59. Lucashenko M. No other truth?: Aboriginal women and Australian feminism. Social Alternatives 1994; 12: 21‐24.

- 60. Forsdike K, Tarzia L, Hindmarsh E, Hegarty K. Family violence across the life cycle. Aust Fam Physician 2014; 43: 768‐774.

- 61. MacMillan H, Wathen C, Varcoe C. Intimate partner violence in the family: considerations for children’s safety. Child Abuse Negl 2013; 37: 1186‐1191.

- 62. Hooker L, Kaspiew R, Taft A. Domestic and family violence and parenting: mixed method insights into impact and support needs: state of knowledge paper. Sydney: ANROWS Landscapes, 2016. https://20ian81kynqg38bl3l3eh8bf‐wpengine.netdna‐ssl.com/wp‐content/uploads/2019/02/L1.16_1.8‐Parenting‐2.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 63. Howarth E, Moore THM, Shaw ARG, et al. The effectiveness of targeted interventions for children exposed to domestic violence: measuring success in ways that matter to children, parents and professionals. Child Abuse Review 2015; 24: 297‐310.

- 64. Gartland D, Conway L, Giallo R, et al. Intimate partner violence and child outcomes at age 10: a pregnancy cohort. Arch Dis Child 2021; 106: 1066‐1074.

- 65. Oram S, Trevillion K, Khalifeh H, et al. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of psychiatric disorder and the perpetration of partner violence. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2013; 23: 361‐376.

- 66. Sesar K, Dodaj A, Šimić N. Mental health of perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Mental Health Review Journal 2018; 23: 221‐239.

- 67. Hegarty K, Forsdike‐Young K, Tarzia L, et al. Identifying and responding to men who use violence in their intimate relationships. Aust Fam Physician 2016; 45: 176‐181.

- 68. Calcia MA, Bedi S, Howard LM, et al. Healthcare experiences of perpetrators of domestic violence and abuse: a systematic review and meta‐synthesis. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e043183.

- 69. Tarzia L, Forsdike K, Feder G, Hegarty K. Interventions in health settings for male perpetrators or victims of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2020; 21: 123‐137.

- 70. Andrews S, Gallant D, Humphreys C, et al. Holistic programme developments and responses to Aboriginal men who use violence against women. Int Soc Work 2021; 64: 59‐73.

- 71. Gallant D, Andrews S, Humphreys C, et al. Aboriginal men’s programs tackling family violence: a scoping review. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 2017; 20: 48‐68.

- 72. Australian Government Department of Health. Clinical practice guidelines: pregnancy care. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/pregnancy‐care‐guidelines (viewed June 2022).

- 73. Hegarty K, McKibbin G, Hameed M, et al. Health practitioners’ readiness to address domestic violence and abuse: a qualitative meta‐synthesis. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0234067.

- 74. Kalra N, Hooker L, Reisenhofer S, et al. Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021; (5): CD012423.

- 75. Paradies Y, Truong M, Priest N. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29: 364‐387.

- 76. Cullen P, Mackean T, Walker N, et al. Integrating trauma and violence informed care in primary health care settings for First Nations women experiencing violence: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2021; doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020985571 [Epub ahead of print].

- 77. Bacchus L, Bewley S, Fernandez C, et al. Health sector responses to domestic violence in Europe: a comparison of promising intervention models in maternity and primary care settings. London: London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, 2012.

- 78. Varcoe C, Wathen C, Ford‐Gilboe M, et al. VEGA — Violence Evidence Guidance Action: briefing note on trauma‐ and violence‐informed care. VEGA Project and PreVAiL Research Network, 2016. https://www.pauktuutit.ca/e‐modules/my‐journey‐healthcare‐provider/presentation_content/external_files/A%20VEGA%20Briefing%20Note%20on%20Trauma‐%20and%20Violence‐Informed%20Care.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 79. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma‐informed approach [HHS publication No. SMA 14‐4884]. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 80. Hegarty K, Gleeson S, Brown S, et al. Early engagement with families in the health sector to address domestic abuse and family violence: policy directions. Melbourne: Safer Families Centre, 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/596d8907b3db2b5b22158a4e/t/5fac48579d560157701e7699/1605126234924/Early+Engagement+Safer+Families+Centre+FINAL+2020.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 81. Public Health Agency of Canada. Trauma and violence‐informed approaches to policy and practice [website]. https://www.canada.ca/en/public‐health/services/publications/health‐risks‐safety/trauma‐violence‐informed‐approaches‐policy‐practice.html (viewed Sept 2020).

- 82. Quadara A. Implementing trauma‐informed systems of care in health settings: the WITH study: state of knowledge paper. Sydney: ANZROWS, 2015. http://media.aomx.com/anrows.org.au/s3fs‐public/WITH%20Landscapes%20final%20150925.PDF (viewed June 2022).

- 83. Chamberlain C, Gee G, Gartland D, et al. Community perspectives of complex trauma assessment for Aboriginal parents: “it’s important, but how these discussions are held is critical”. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 2014.

- 84. PriceWaterhouseCoopers Australia. A high price to pay: the economic case for preventing violence against women. PwC, 2015. https://www.pwc.com.au/pdf/a‐high‐price‐to‐pay.pdf (viewed June 2022).

- 85. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Abuse and violence: working with our patients in general practice, 5th ed. [White Book]. Melbourne: RACGP, 2021. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical‐resources/clinical‐guidelines/key‐racgp‐guidelines/view‐all‐racgp‐guidelines/abuse‐and‐violence/about‐this‐guideline (viewed June 2022).

Summary